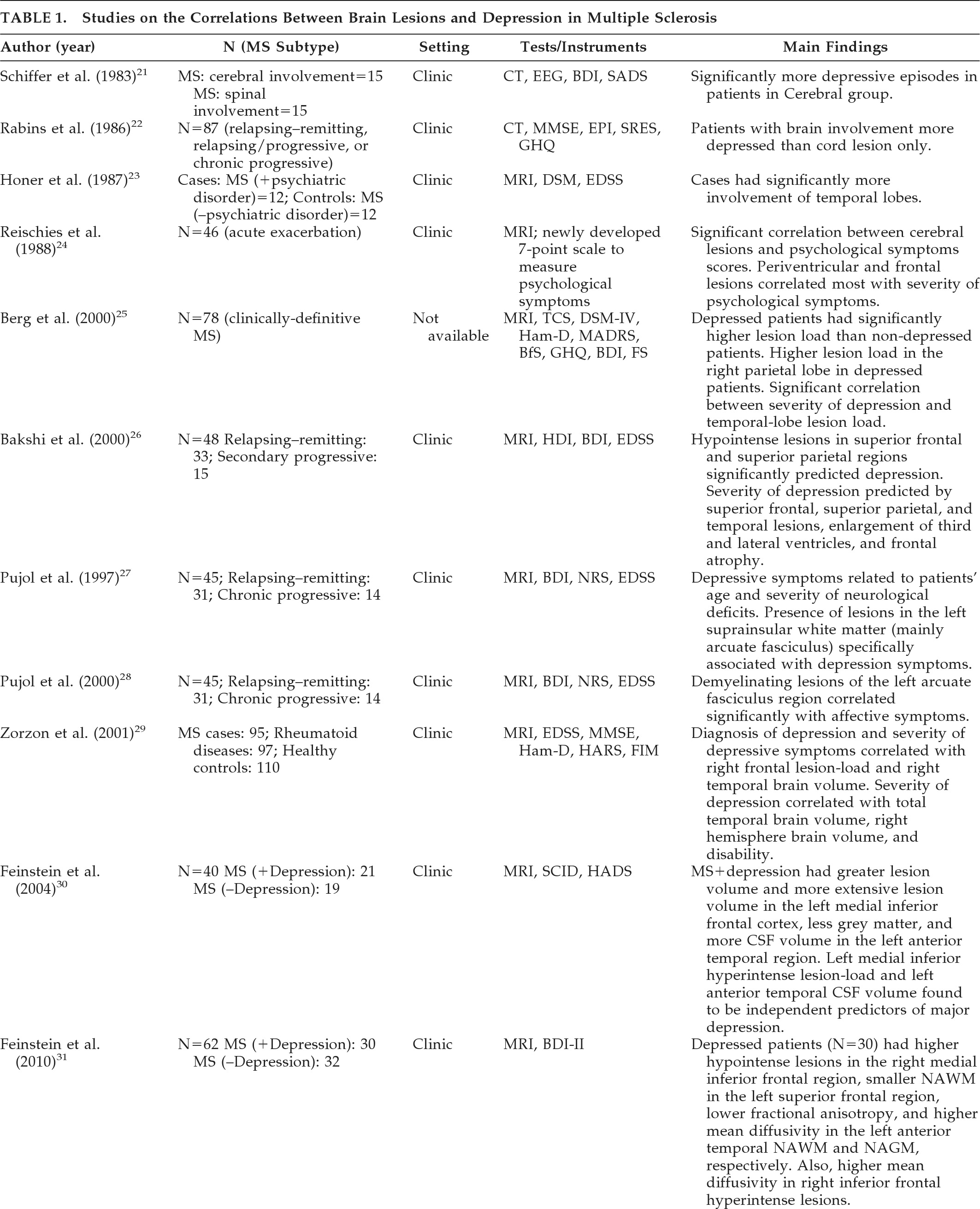

Schiffer et al.

21 investigated 30 patients with MS; 15 patients fulfilled the criteria for cerebral involvement, and 15 had cerebellar or spinal cord involvement. The criteria for cerebral involvement included neurological findings on examination, abnormal EEG, and abnormal CT scans. According to assessment measures (the Beck Depression Inventory [BDI], and a psychiatric interview patterned after the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia [SADS]), there were significantly more depressive symptoms in the patient group with cerebral involvement. Rabins et al.

22 studied 87 patients with MS. The treating neurologist characterized MS subtypes (relapsing–remitting, relapsing/progressive, or chronic-progressive) and determined whether the patient only suffered spinal cord involvement or had evidence of brain involvement. CT head scans were performed on 37 patients with brain involvement, and ventricle-to-brain ratio was determined. The General Health Questionnaire was used to assess patients' emotional states. Patients also received the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE), the Eysenck Personality Inventory (EPI), and the Holmes-Rahe Schedule of Recent Experiences (SRE). Patients with MS who had brain involvement were more depressed than patients with spinal cord lesion only. Moreover, euphoric patients (i.e., patients with inappropriately cheerful mood) were more likely to have progressive MS with brain involvement and enlarged ventricles, and were more likely to be cognitively impaired than the non-euphoric patients. It should be mentioned that the clinical picture of MS can be associated with both euphoria (exaggerated mood elation) and eutonia (increased sense of physical fitness). Honer et al.

23 compared the brain MRI findings from 12 patients with MS and psychiatric disorders with 12 matched patients without psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric data were obtained from case notes, and diagnoses were made using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd Edition (DSM-III) criteria. The Kurtzke/Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score was used to measure disability. Analysis of data showed that patients with MS and psychiatric disorders had significantly more pathological involvement of the temporal lobes. Of note, this study did not specifically investigate depression in MS, and the case group had patients with other affective disorders, organic personality disorders, and organic hallucinosis. Reischies et al.

24 investigated 46 patients with MS, using brain MRI. All patients had psychological symptoms assessed using a newly-developed 7-point scale that measured symptoms of depressed mood, irritability, reduced drive, and disorders of judgment. The authors found a significant correlation between cerebral lesions and psychological-symptom scores. Periventricular and frontal lesions appeared to correlate most with severity of psychological symptoms. As in the previous study, they did not specifically investigate depression in MS, and the reliability and validity of the scale they developed to assess psychological symptoms is questionable. Berg et al.

25 studied 78 patients who fulfilled diagnostic criteria for MS, using neurological, neuropsychiatric and neurophysiological assessment, MRI, and transcranial sonography (TCS). The study aimed to assess whether specific changes of the basal limbic system could be identified in patients with MS and depression; 39.7% of patients fulfilled DSM-IV criteria for depression. The authors did not find any significant alteration of the basal limbic system in the depressed group versus the nondepressed group. However, post-hoc analysis showed that depressed patients had significantly higher lesion-load than nondepressed patients, particularly in the right parietal lobe. A significant correlation was detected between the severity of depression (assessed using the BDI, the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [Ham-D], and the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Scale [MADRS]), and the lesion-load in the temporal lobe. Scores on the Fatigue Scale (FS) and lesion-load in right temporal lobe also showed a significant correlation. Bakshi et al.

26 assessed the severity of depression in 48 patients with MS, using the BDI and the Hamilton Depression Inventory (HDI). Neurological disability was measured with the EDSS. Hypointense lesions on T1-weighted images in superior frontal and superior parietal regions significantly predicted the presence of depression, both before and after adjusting for EDSS scores. Severity of depression was predicted by superior frontal, superior parietal, and temporal lesions, enlargement of the third and lateral ventricles, and frontal atrophy. Pujol et al.

27 studied 45 patients with a definite clinical diagnosis of MS and evidence of cerebral demyelinating lesions on routine brain MRI. All subjects were assessed during a stable period of their illness (at least 3 months before recruitment without relapse or progression). Depressive symptoms were measured with the BDI; neurological symptoms were assessed with the Neurologic Rating Scale (NRS); and disability was assessed with the EDSS. Patients were also assessed using a specific MRI protocol to quantify lesions separately in the basal, medial, and lateral-frontotemporal white matter. Depressive symptoms were weakly but significantly related to patients' age and severity of neurological deficits. The presence of lesions in the left suprainsular white matter (arcuate fasciculus) was specifically associated with depressive symptoms. Pujol et al. conducted a further study with the same group of patients to establish the significance of the previously reported association between depressive symptoms and demyelinating lesions in the region of the left arcuate fasciculus in patients with MS.

28 Patients were requested to complete the BDI. The BDI was broken down into main symptom categories according to the results of factor-analytic studies, and correlation patterns between BDI subscores and lesion measurements were analyzed. Demyelinating lesions of the left arcuate fasciculus region correlated significantly with affective symptoms (sadness, pessimism, suicidal ideas, irritability, and social withdrawal) and somatic complaints (insomnia, loss of appetite, weight loss, and somatic preoccupation), with the former showing the highest correlation. The arcuate fasciculus is a major component of suprainsular white matter that is laterally located in the brain and includes several reciprocal connections of the frontal lobe with posterior cortices.

The left hemisphere appears to be more involved than the right hemisphere in the control of motivation-related emotional activity.

28 Zorzon et al.

29 investigated the relationship between involvement of specific brain areas and the occurrence of anxiety and depression. A group of 95 patients with clinically definitive MS were recruited; 97 patients with other chronic rheumatoid diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, ankylosing spondylitis, and psoriatic arthritis were recruited; 110 healthy subjects were also recruited as controls. All subjects underwent a full neurological examination, and assessments using EDSS, Functional Independence Measure (FIM), Ham-D, and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (Ham-A). Diagnosis of depression was made using DSM-IV criteria. In all, 18% of participants with MS, 16% of controls with RA, and 4% of healthy volunteers fulfilled DSM-IV criteria for major depression. All the patients with a diagnosis of MS underwent MRI examinations. Regional and total lesion-loads were calculated. Both diagnosis of depression and severity of depressive symptoms correlated weakly with right frontal lesion-load and right temporal brain volume. The severity of depression correlated significantly with total temporal brain volume, right hemisphere brain volume, and disability. Anxiety did not correlate significantly with any regional and total lesion-loads, brain volume, or any considered clinical variables. The authors suggested that anxiety and depression may have different etiologies in patients with MS. Depression may be caused by brain damage related to MS, whereas anxiety may be a reactive response to psychosocial pressures. Feinstein et al. studied 40 patients with MS.

30 All patients were initially screened with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Rating Scale (HADS), and those who scored ≥10 were interviewed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID); 19 patients had depression, and 21 did not have depression. Compared with euthymic patients, patients with depression had a greater T2-weighted lesion volume and more extensive T1-weighted lesion volume in the left medial inferior frontal cortex. They also had less gray matter and more CSF volume in the left anterior temporal region. Degree of contribution of brain abnormalities to the development of depression was calculated by a logistic-regression model. Hyperintense lesion-load in the left medial inferior frontal cortex and left anterior-temporal CSF volume (an index of regional cerebral atrophy) were found to be independent predictors of major depression.

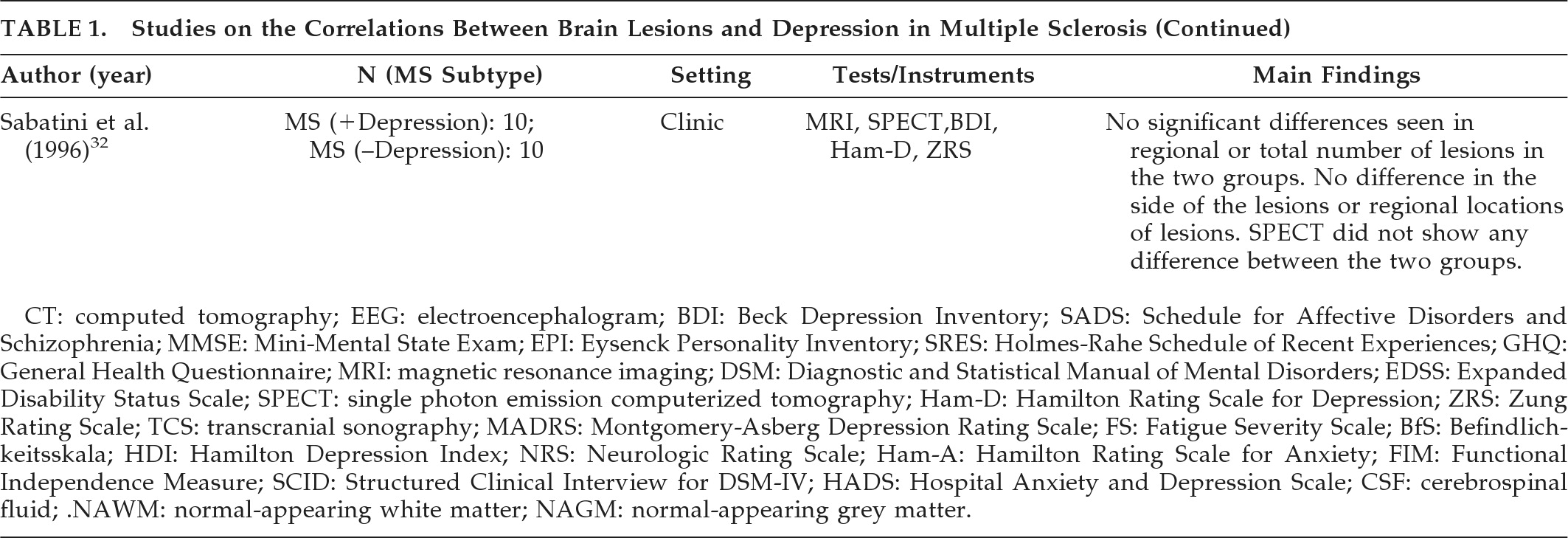

In summary, imaging studies to-date vary widely in both their design and methodology. There are few, if any, unequivocal conclusions that can be made from these studies. Most studies used poor rating scales for depression, particularly the BDI, which has too much loading on somatic symptoms. The correlation between lesion location and depression in MS appears less precise than in poststroke depression.

9 This may be because most of the older studies investigated the relationship between depressive symptoms and brain atrophy and demyelinating lesions that were clearly evident on the available imaging techniques, potentially missing more subtle disease. However, newer and more sophisticated brain imaging techniques have shown subtle neuropathological changes even in patients deemed to have benign disease. These changes have been linked to neurological and cognitive dysfunction and depression.

31 Further research is needed to improve our understanding of the neuropathology of depression and how precisely this relates to MS. Better tools for future research include voxel-based morphometry and MRI techniques that examine connectivity between different areas. Better visualization of cortical and deep white-matter pathology, together with quantitative MRI techniques, such as diffuse tensor imaging, may improve our understanding of this association. Conclusions from earlier studies that subdivided patients with MS into those with and without brain pathology will have to be judged more critically, as the split is likely to be rendered less clear if current imaging techniques to visualize lesional and non-lesional brain pathology were available when the studies were performed. Nevertheless, the available evidence seems to suggest an association between depression in MS and greater neuropathology in frontal, temporal, and parietal regions.