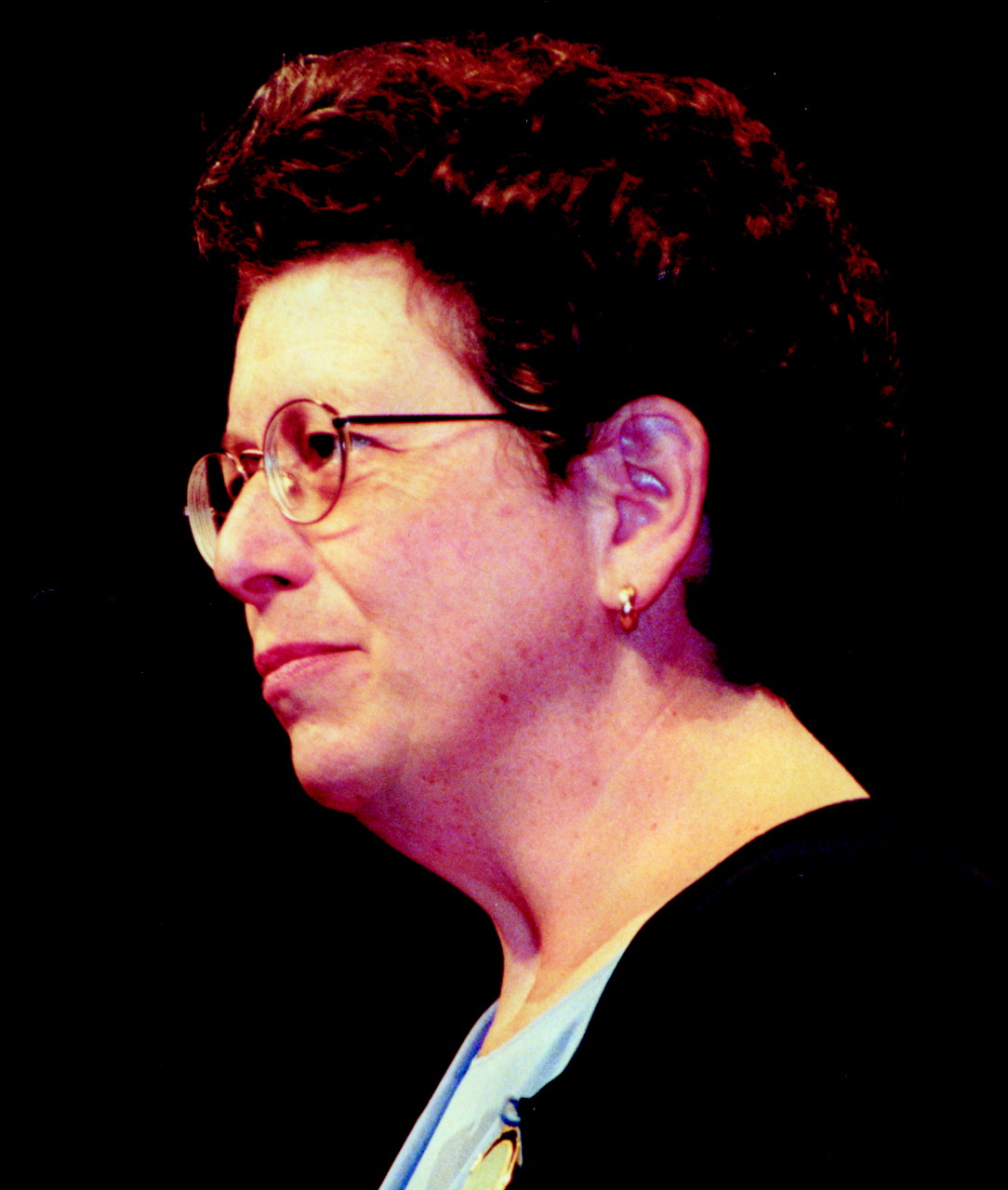

Psychiatrists who belong to a wide range of racial or ethnic minority groups account for a steadily increasing proportion of this country’s psychiatrists. To improve APA’s ability to represent and respond to the unique needs of psychiatrists who are members of ethnic or other minorities—some of whom are APA members, many of whom are not—Assembly Speaker Nada Stotland, M.D., convened a meeting last month that brought together representatives of several minority-oriented psychiatric organizations and leaders of APA.

The meeting took place on November 11 and 12 in Washington, D.C., in conjunction with the fall meeting of the APA Assembly.

“The existence of separate organizations tells us that APA is not meeting all the professional needs of our members,” Stotland said. “The elected leaders of these organizations have much to teach us about the backgrounds, activities, concerns, and needs of many of our colleagues and patients” who are among the constituencies these groups represent.

The Assembly was represented at the meeting by representatives of its seven minority/underrepresented groups and the Assembly’s elected leadership (all of whom for the first time are members of minority/underrepresented groups, Stotland pointed out). Other APA leaders attending were President Richard Harding, M.D., President-elect Paul Appelbaum, M.D., Medical Director Steven Mirin, M.D., and Division of Education, Minority, and National Programs Director James Thompson, M.D.

Each minority organization’s representative described its activities and plans. The representative of the Korean-American psychiatrists, for example, explained that the group held a two-day symposium for Korean-American religious leaders in conjunction with APA’s annual meeting held in Chicago last year. The Pakistani-American psychiatrists have been wrestling with “poignant emotional stresses stemming from recent developments in Pakistan,” Stotland said. She added that most of the organizations use newsletters to keep in touch with their members and with colleagues in their countries of origin and try to hold meetings in conjunction with APA’s annual meeting.

Dozens of suggestions to enhance the relationship between the minority psychiatric organizations and APA arose from the meeting. Among them are that APA should

• provide membership data to these organizations that include contact information and other data so that they can communicate with psychiatrists who might be interested in joining one of these minority organizations;

• undertake more outreach efforts in which its leaders would visit public psychiatry settings and meetings of minority psychiatrist organizations;

• appoint more members of minority groups to APA components;

• develop a formal document describing the elements that go into making up culturally competent psychiatric care;

• encourage more research on minority mental health issues;

• devote resources to recruiting minority physicians into psychiatry;

• make more of an effort to include public-sector psychiatrists, most of whom are members of minority groups, into its policymaking and other discussions;

• offer more annual meeting courses in Spanish;

• try to increase the numbers of black psychiatrists who serve as examiners for the ABPN board-certification examination;

• work with the American Society of Hispanic Psychiatrists in the selection of the recipient of the annual Simon Bolivar Award.

The groups that sent representatives to the meeting were the Association of American Indian Physicians, American Society of Hispanic Psychiatrists, Association of Chinese-American Psychiatrists, Association of Gay and Lesbian Psychiatrists, Association of Korean-American Psychiatrists, Association of Women Psychiatrists, Black Psychiatrists of America, Indo-American Psychiatric Association, and Pakistani Psychiatrists Association of North America. ▪