Early intervention improves outcomes for children with developmental delays, but performing routine, formal developmental screening as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics can be a challenge for busy pediatricians. The experience of pediatric staff at a large medical practice in Eugene, Ore., however, has demonstrated that a systematic screening program in which parents fill out a validated assessment questionnaire can dramatically increase the number of children identified with potential problems that required further evaluation.

The program is described and its effects are analyzed in an article in the August Pediatrics by Hollie Hix-Small, Ph.D., and colleagues.

In the period between April 1, 2005, and March 1, 2006, a simple process was incorporated in routine well-child visits at 12 or 24 months. At each visit, a parent or caregiver was given the Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ), a 30-item, screening tool for monitoring child development, which has been shown to be valid and reliable for children between 4 months and 5 years old. Participants in the program had the option to complete the questionnaire at home and mail it in or complete the questionnaire at the medical office.

The research staff reviewed the completed questionnaires and referred children with suspected developmental problems to the Program for Infants and Toddlers (part C of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act [IDEA], a federal grant program) based on predetermined criteria for ASQ scores. Meanwhile, pediatricians at the practice independently saw these children as a part of standard care, documented their ratings of each child's developmental status and determined whether the child needed a referral to the same part C agency evaluation. The pediatricians were unaware of the children's ASQ scores.

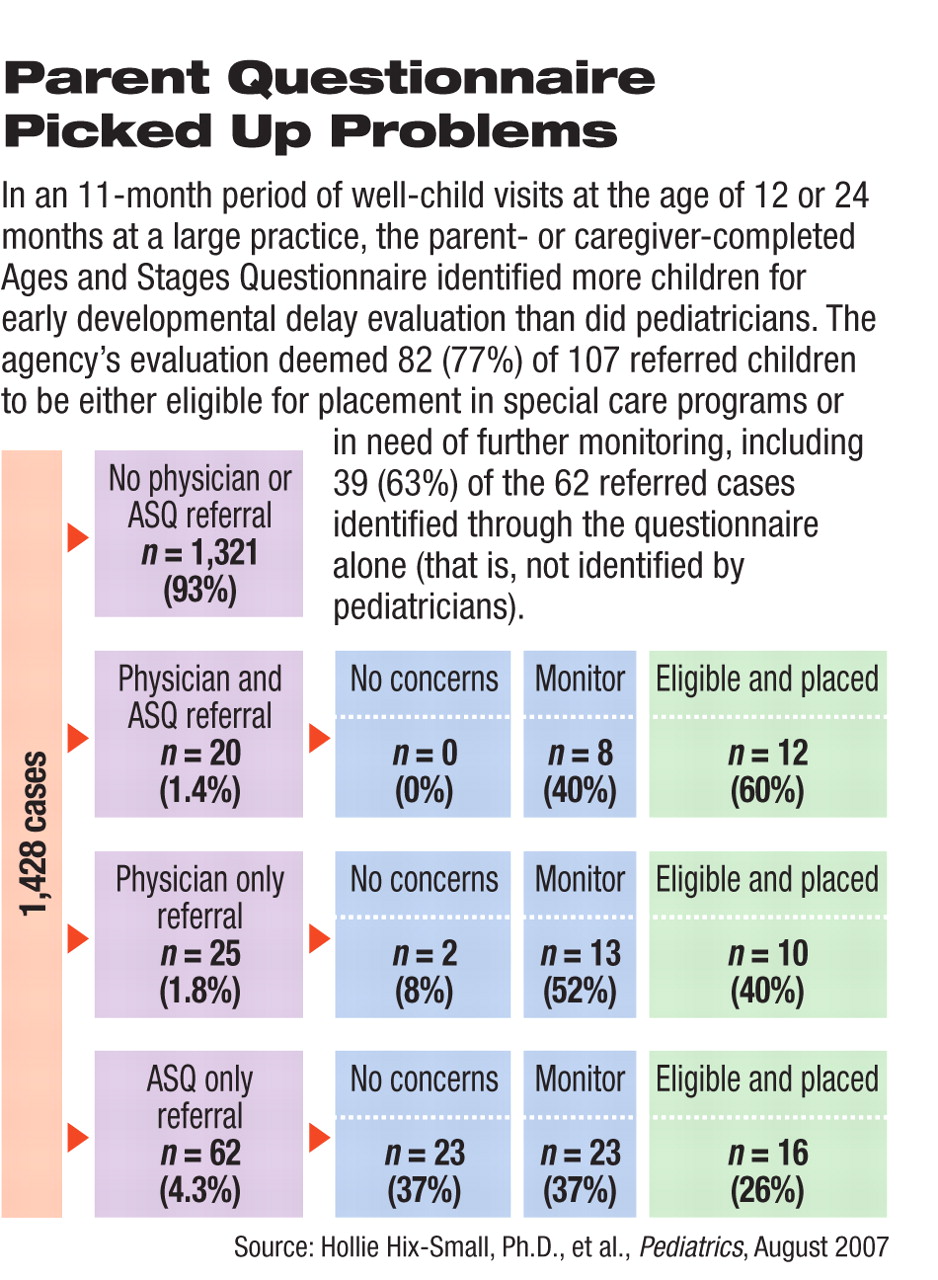

The result was impressive: out of 1,428 children who were seen at the practice, 107 children were referred to an IDEA part C agency for further developmental evaluations. That represented a 224-percent increase over the period April 2003 to March 2004, when only 33 referrals were made. On the basis of their clinical impression alone, physicians referred 45 children, while researchers identified and referred 82 children on the basis of ASQ scores. Only 20 were cases overlapping from both processes.

Of all the referrals, 25 children were screened out by the state's part C agency as “no concern,” 38 met the eligibility criteria for IDEA part C special-education services immediately, and 44 were scheduled for future screening because of suspected developmental delays.

Once a child is referred to a part C agency, the agency contacts the parents or caregiver and conducts further evaluations to determine whether the child is eligible for state-provided care.

The authors cited the importance of early intervention, which requires early detection of signs or symptoms, to achieve optimal outcomes for children with developmental delays. Although the American Academy of Pediatrics has published guidelines for identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders, busy pediatricians may find it challenging to use these algorithms during routine visits. In contrast, the ASQ can be completed by parents or caregivers at home and potentially teach them possible signs to look for in children.

“One anecdotal observation in the clinic was that often the act of filling out the ASQ increased the parent's observational skills for child development,” Hix-Small told Psychiatric News.

The authors estimated that the cost of incorporating the screening program, including distributing the ASQ to parents or caregivers upon check-in and collecting the forms at the clinic or by postage-paid mail, was only $1.61 to $2.43 per patient. Kevin Marks, M.D., one of the study authors and a physician at the medical practice group, noted that “the ASQ screening system was found to be feasible [and] low cost and did not impede office flow.”