Remember the 1985 film “Back to the Future,” in which a teenager traveled back in time and met his parents while they were in high school?

In a way, it is analogous to a hypothesis proposed by Daniel Schacter, Ph.D., a professor of psychology at Harvard University, that our memories play a substantial role in helping us prepare for the future.

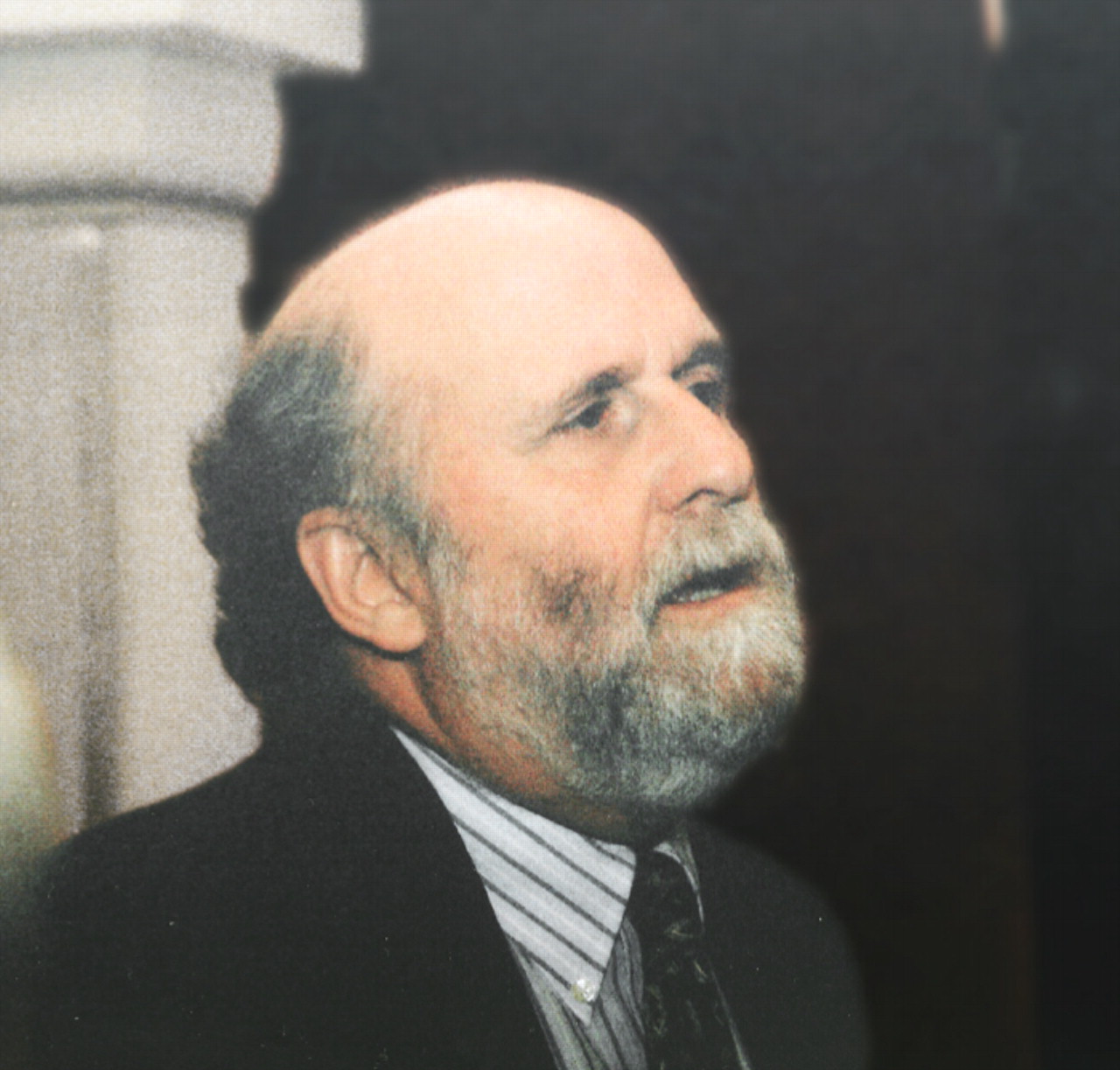

Or as Schacter put it at the annual meeting of the American Psychoanalytic Association in New York in January: “Episodic memories might allow us to engage in mental time travel.” Schacter was invited to give a plenary address at the meeting because he is an internationally recognized human-memory authority.

A number of years ago, Schacter said, a man with severe brain damage could neither remember past episodes nor visualize any episode that might happen in the future. These deficits suggested to Schacter that there might be a link between episodic memory and visualization of the future. But how might he study such a hypothesis? He didn't know, so it “went on my back burner for 20 years,” he said.

During the past decade or so, though, he and his colleagues have conducted experiments that bolster the hypothesis.

For example, they put 14 college students in an fMRI brain scanner, then asked the students to recall past events or visualize the future. Meanwhile, they observed the brain activity of the students.

“We were struck by the similarities in brain activity when subjects either recalled past events or visualized future events,” he said. “The hippocampus, the major memory center of the brain, was extremely active in both instances. So it looks as if the hippocampus is involved in both remembering and imagining.”

They also found in other experiments that the entire medial temporal lobe, which includes the hippocampus, as well as the medial prefrontal cortex are involved in both recollecting the past and imagining the future. And while activity in the back of the hippocampus is linked with both recalling and imagining, activity in the front of the hippocampus is associated with imagining only.

So if there are indeed links between recalling and imagining, and if the same brain areas are involved in both activities, then it's possible that the human brain uses memories to prepare for the future, Schacter contends. “We think that fragments of memories are recombined to visualize future scenarios without actually carrying them out. It's economical because it doesn't involve any actual risk. It's a simulation, if you will—memory of the future.”

Of course, if such a system really exists, it could have a drawback, he pointed out. Fragments of memories could be recombined inaccurately and thus lead to false memories. “Certainly it's not news that our memories can distort things. Even Freud knew that.”

In any event, if recalling past events helps people imagine future ones, it has implications for analysis and psychiatry, Schacter believes.

For example, Schacter and his group compared the memory and visualization abilities of 16 older adults who had mild Alzheimer's disease with the memory and visualization abilities of 16 older mentally healthy adults. They found that the former were not as capable as the latter at either task. Thus, Alzheimer's appears to impair both recall and imagining.

Still another study, conducted by other researchers, suggests that depression can do so as well. Depressed patients were found to experience a deficit in both remembering and visualizing future events.