Last year, Anita Thapar, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at Cardiff University in Wales, and her team reported a genomewide association study that they believed established for the first time a genetic basis for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

In that study, which was based on genetic material from 366 children with ADHD and 1,047 controls, they were able to link some rare gene duplications or omissions with the illness (Psychiatric News, November 5, 2010).

Since then, they have conducted a more extensive ADHD genomewide association study, analyzing genetic material not just from the 366 children with ADHD in the previous study, but from 361 additional children with ADHD and 5,081 comparison subjects. And their results were largely the same as the first time around, they reported November 8 in AJP in Advance.

Specifically, they found a significantly higher rate of rare gene deletions or rare gene duplications in children with ADHD than in comparison subjects. And even when they focused solely on the new children with ADHD in this study, this was the case.

“We were pleased that our previous findings were replicated,” Thapar told Psychiatric News.

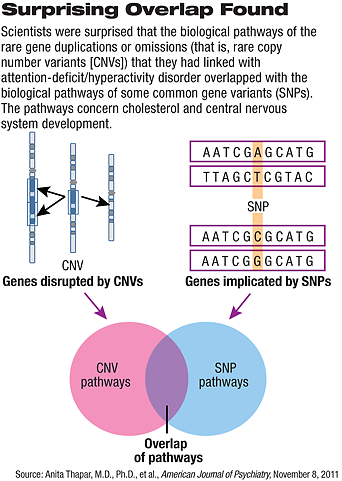

“We were [also] surprised that the biological pathways affected by these rare genetic variants overlapped with those affected by common [gene variants or SNPs],” she added. In other words, “even though the common variants didn’t reach the very stringent statistical thresholds required to say they are risks, they still seemed to be affecting biological pathways that are affected by the rare copy number variants that were for sure statistically significant. It highlights for me that by dismissing associations that are nonsignificant, maybe we are throwing away potentially valuable information. It also shows how complex it will be capturing different types of genetic risks.”

A gene duplication of particular interest also emerged from the scientists’ findings. It was found to be present in six children with ADHD, but in none of the comparison subjects. The duplication concerned a gene called CHRNA7. It encodes the alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor; is widely expressed in the brain, especially in the hippocampus; is involved in rapid synaptic transmission; and has been implicated in schizophrenia (Psychiatric News, July 18, 2008).

“There needs to be further investigation of CHRNA7 and the biological pathways in which it is involved before we can think about what it might mean clinically,” Thapar said. “[But] if specific biological pathways are involved, then it could give clues about treatments.”

It is too early to know whether any of the researchers’ other findings might have clinical implications, she pointed out. But the 13 biological pathways that she and her colleagues linked to variations in both gene number and variations in gene composition are known to affect the development of the central nervous system. Four of the 13 concern cholesterol, which is an important brain component.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust and the United Kingdom Medical Research Council.