Poor young women are at risk of depression (

1 ), and those who are from an ethnic minority group are particularly unlikely to get care (

2 ). Fewer than 9% of U.S.-born Latinos seek care from mental health settings, and fewer than 20% seek such care in general health care settings (

3 ). Immigrant Latinos are even less likely to get mental health treatment (

3 ). African Americans are more likely than Latinos to get depression care, but they are underserved compared with their white counterparts (

4,

5,

6,

7 ). Little is known about the mental health service utilization of immigrant black women from Africa and the Caribbean. In this study, we examined the relationship of stigma to wanting and getting mental health care for low-income U.S.-born and immigrant Latina and black women.

Poor persons from ethnic minority groups face many practical barriers to care, such as lack of insurance and transportation (

8,

9 ). Although minimizing insurance-related barriers to mental health care improves access (

10,

11,

12 ), blacks and Latinos remain less likely than whites to receive services, even when they have the same insurance coverage (

13,

14 ). Stigma about mental illness may keep poor women from ethnic minority groups from seeking treatment for common mental disorders (

15,

16 ) and might therefore be an important factor in explaining disparities in care.

Depression is a stigmatized condition (

17,

18,

19 ), and persons who are depressed report more stigma associated with depression than do those who are not depressed (

20,

21,

22 ). Small studies have produced conflicting results regarding the role of stigma in seeking mental health care among low-income women from ethnic minority groups. Although many women report stigma concerns in talking to primary care clinicians about mental health issues (

23 ), Latina and black women are more likely than white women to endorse stigma concerns (

20,

24 ). Similarly, Caribbean immigrants to Canada and the United Kingdom report concerns about being labeled as "crazy" (

25 ), which reduce their willingness to engage with mental health services (

26,

27 ). Nigerians have also been found to have high levels of stigma concerns and negative attitudes in regard to mental illness, although not specifically to depression (

28 ). However, other research suggests that stigma plays a minimal role in service utilization (

7 ), with low-income African-American, Latina, and white women endorsing logistical barriers to care to a far greater extent than stigma (

20,

29 ) and few women reporting stigma concerns overall (

29 ). These early studies have relatively small samples and do not distinguish between immigrants and U.S.-born minorities.

Little is known about the relation of stigma concerns to wanting and using mental health services. A study of depression and stigma among primary care patients demonstrated that although many patients reported stigma concerns, stigma was not associated with being in treatment (

30 ). Stigma may affect treatment seeking for some individuals (

31,

32,

33,

34 ), but little is known about the extent to which stigma influences wanting and being in mental health care among women who are from ethnic minority groups.

In this study, we examined stigma-related concerns about mental health care among immigrant and U.S.-born black and Latina women compared with U.S.-born white women. First, we examined ethnic differences in stigma among women with depression and among women without depression, allowing us to assess the specific experiences of women with depression and general attitudes among women without depression who have similar backgrounds. We then examined whether stigma-related concerns about seeking care were related to wanting or being in mental health treatment among those needing care for depression, paying particular attention to the differential impact of stigma among women from ethnic minority groups and immigrant women.

Methods

Participants

Between March 1997 and December 2001 a total of 15,383 low-income women were screened for the Women Entering Care (WE Care) depression treatment study (

35,

36 ) in county health settings, including Women, Infants and Children (WIC) clinics (WIC provides nutritional services to low-income pregnant and postpartum women and their children up to age five) and Title X family planning clinics (Title X provides comprehensive family planning services for low-income women). A small number were screened in pediatric clinics and a subsidized housing project. All participants provided written informed consent in English or Spanish. Immigrant black women served in these settings spoke either English or Spanish. Seventy-nine percent of the immigrant Latina women were from Central America (for example, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Nicaragua), 15% were from South America (for example, Chile and Bolivia), and the remainder were from the Caribbean or Mexico. Country of origin information was not available for immigrant black women. Among those approached, only 8.8% declined participation. Research procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of Georgetown University, the State of Maryland, and the University of California, Los Angeles.

Measures

Measures were administered orally in the participants' preferred language (English or Spanish) by WE Care project staff in a private room at each of the different service settings.

Depression. The Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD) (

37 ) was used to identify women who were depressed. On the basis of

DSM-IV criteria, the PRIME-MD demonstrates good agreement (92%) with independent psychiatric diagnoses made using a structured interview and has been used with ethnic minority populations (

37 ).

Stigma-related concerns about mental health care. A stigma variable was created from three yes-or-no items in response to the query, "Would any of the following keep you from getting professional help?" Participants were categorized as having stigma-related concerns if they endorsed one or more of the following: "being embarrassed to talk about personal matters with others," "being afraid of what others might think," and "family members might not approve."

Logistical barriers. Responding to the same stem question, participants were coded with a logistical barrier to care if they indicated that they endorsed "couldn't afford it/no insurance," "had no time," "no transportation," or "no child care." Items for both stigma and logistical barriers were taken from Sussman and colleagues (

7 ).

Treatment. Participants responded to the following yes-or-no question: "Are you interested in receiving mental health treatment?" They also indicated whether they were currently in treatment. These categories were not mutually exclusive.

Demographic characteristics. Participants provided demographic information including age, marital status, employment status, insurance status, number of children, education, and years in the United States. Information regarding ethnicity and birthplace was obtained via the following two items: "What is your cultural or ethnic identity?" and "Where were you born?"

Analysis

Simple descriptive statistics were used to characterize the samples. In order to examine our research questions, we conducted a series of logistic regressions. The first addressed rates of stigma endorsement across ethnic groups among women with depression and among those without depression, controlling for sociodemographic variables. The second set was limited to the subgroup with depression, examining how ethnicity and stigma predict wanting and being in treatment after controlling for demographic characteristics and logistical barriers to care. The third set of analyses used interaction models to examine how stigma might be differentially related to wanting treatment and being in treatment across ethnic categories in the subsample with depression. Regressions predicting wanting treatment excluded persons who were already in treatment.

Because of reduced sample sizes when restricting analyses to the depressed group, stigma-by-ethnicity interaction models with the original ethnic categories had low or zero cell counts in particular covariate patterns, preventing detection of meaningful effects. In order to examine differences with respect to minority and immigrant status in general, we regrouped our ethnic categories into U.S.-born whites, U.S.-born persons from ethnic minority groups (U.S.-born blacks and U.S.-born Latinas), and immigrants from minority groups (African-born and Caribbean-born blacks and immigrant Latinas) and ran interaction models with these groupings. We calculated adjusted rates for wanting treatment and being in treatment by stigma endorsement by each category, setting all control covariates at the mean for the entire subsample with depression. From the interaction models, we also estimated odds ratios for stigma versus no stigma for each category.

We had small amounts of missing data. Demographic variables all had less than .5% missing data, with the exception of ethnicity (1%) and years living in the United States (approximately 5% for immigrants). None of the barriers to care or stigma items had missing data. Both our outcome variables, wanting to be in care and being in care, had approximately 5% missing data. To examine the influence of missing data on our parameter estimates, we reran analyses using multiple imputation. Demographic items were imputed with an approximate Bayesian bootstrap predicted mean matching hot-deck procedure, in sequential order of least to most missing data (

38,

39 ). After imputing demographic variables, treatment variables were imputed separately for participants with depression and for those without depression. Analyses were then rerun with five imputed data sets, adjusting standard errors for the uncertainty introduced by imputation. All significant and nonsignificant differences were replicated with the imputed data sets, so we present only the unimputed data.

Results

Sample characteristics

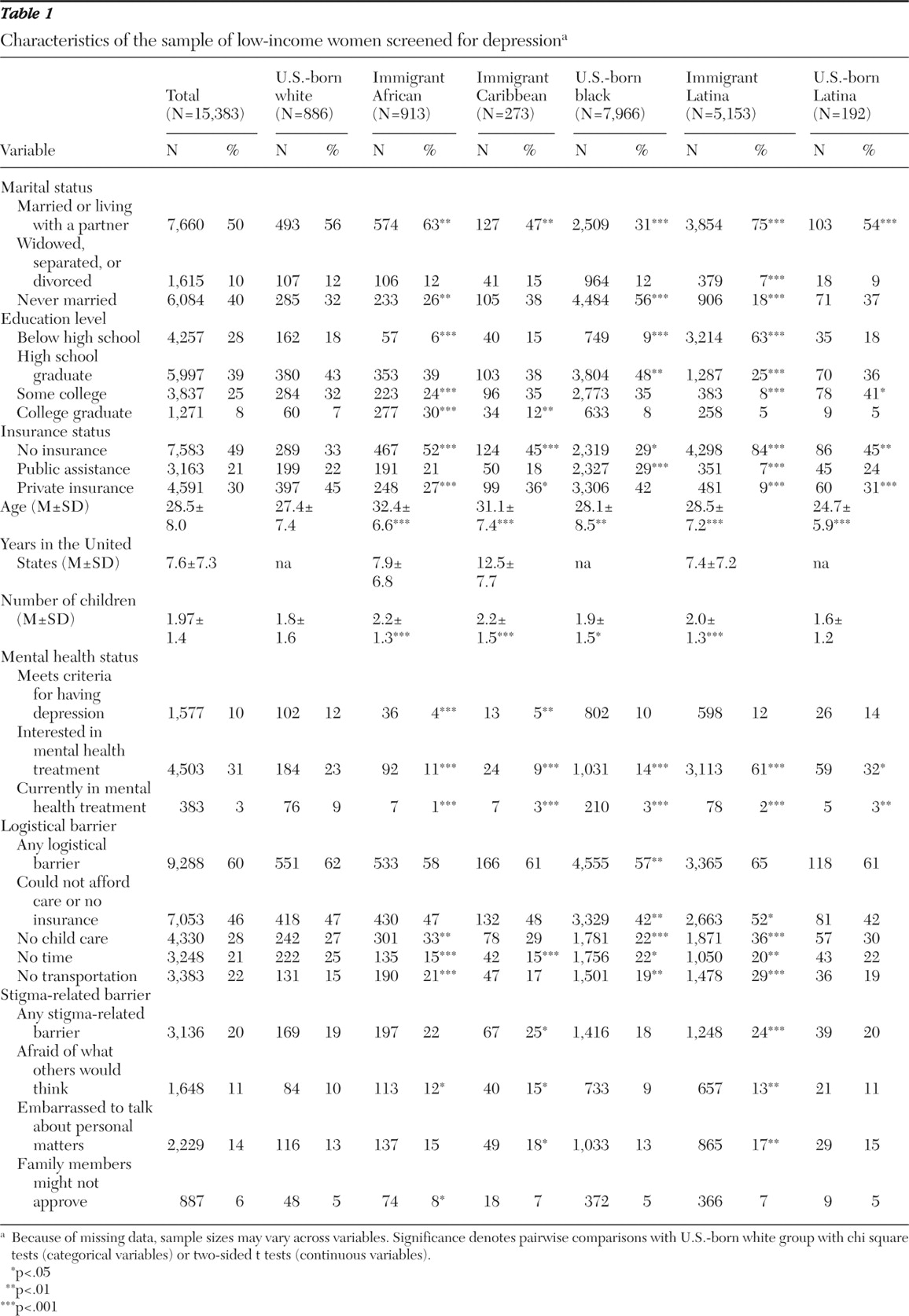

As reported in

Table 1, the sample consisted of 192 (1.2%) U.S.-born Latinas, 5,153 (33.5%) immigrant Latinas, 7,966 (51.8%) U.S.-born blacks, 913 (5.9%) immigrant Africans, 273 (1.8%) immigrant Caribbeans, and 886 (5.8%) U.S.-born whites. The women were relatively young (mean±SD age=28±8 years), about half were married or living with a partner, and nearly a third did not complete high school. About 8% of the women had graduated from college. About half were uninsured, and 21% had medical assistance. Immigrants had been in the United States on average just over seven years. There were many significant differences between women from ethnic minority groups and U.S.-born white women. Demographic variables were controlled for in subsequent analyses.

Overall, 10% (N=1,577) of our sample screened positive for symptoms of major depression. Women endorsed logistical barriers to care more than stigma-related concerns (60% versus 20%). Among women with depression, only 129 (8.2%) were in treatment (21 white women, or 21%, and 108 women from ethnic minority groups, or 7%). However, 71% (N=1,111) of the women were interested in treatment (81 white women, or 81%, and 1,030 women from ethnic minority groups, or 69%). [Demographic characteristics stratified by depression status are available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

Differences in stigma-related concerns about care

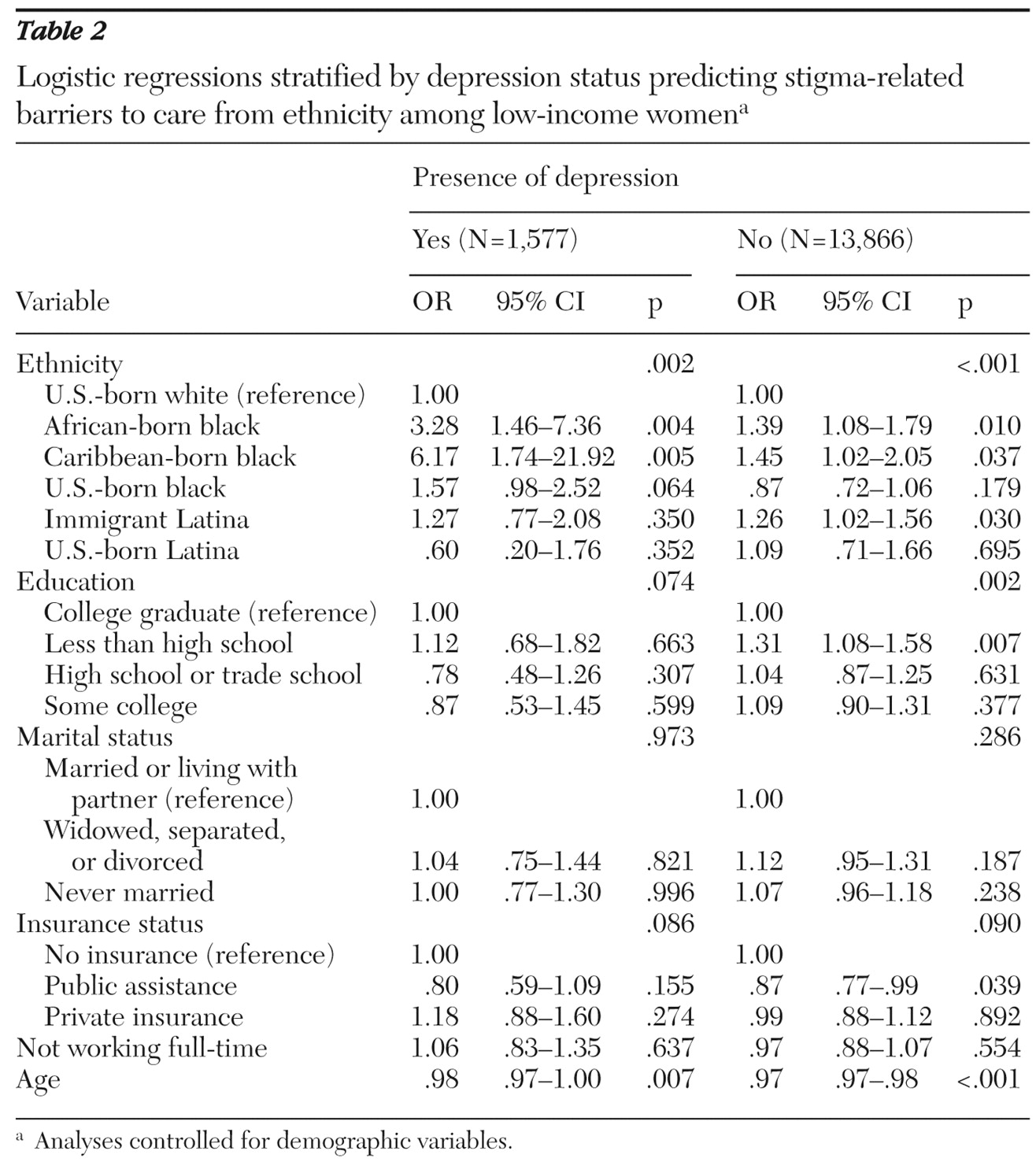

After controlling for demographic characteristics, logistic regression predicting stigma from depression revealed that compared with women without depression, women with depression were 2.25 (p<.001) times more likely to endorse stigma concerns about care. As such,

Table 2 shows the logistic regressions stratified by depression status predicting stigma from ethnicity, controlling for all other demographic characteristics. Ethnicity was a significant predictor in both the group with depression (p=.002) and the group without depression (p<.001). In the group with depression, the black immigrant groups were more likely than U.S.-born whites to endorse stigma concerns (Africans, OR=3.28, p=.004; Caribbeans, OR=6.17, p=.005). There was a trend in the same direction for U.S.-born blacks (OR=1.57, p=.064). Among those with depression, U.S.-born and immigrant Latinas did not differ significantly from whites.

The magnitude of the ethnic differences was smaller in the group without depression, although it was still apparent. Compared with U.S.-born whites, immigrant black women (Africans, OR=1.39, p=.010; Caribbeans, OR=1.45, p=.037) and immigrant Latinas (OR=1.26, p=.030) were more likely to report stigma-related concerns.

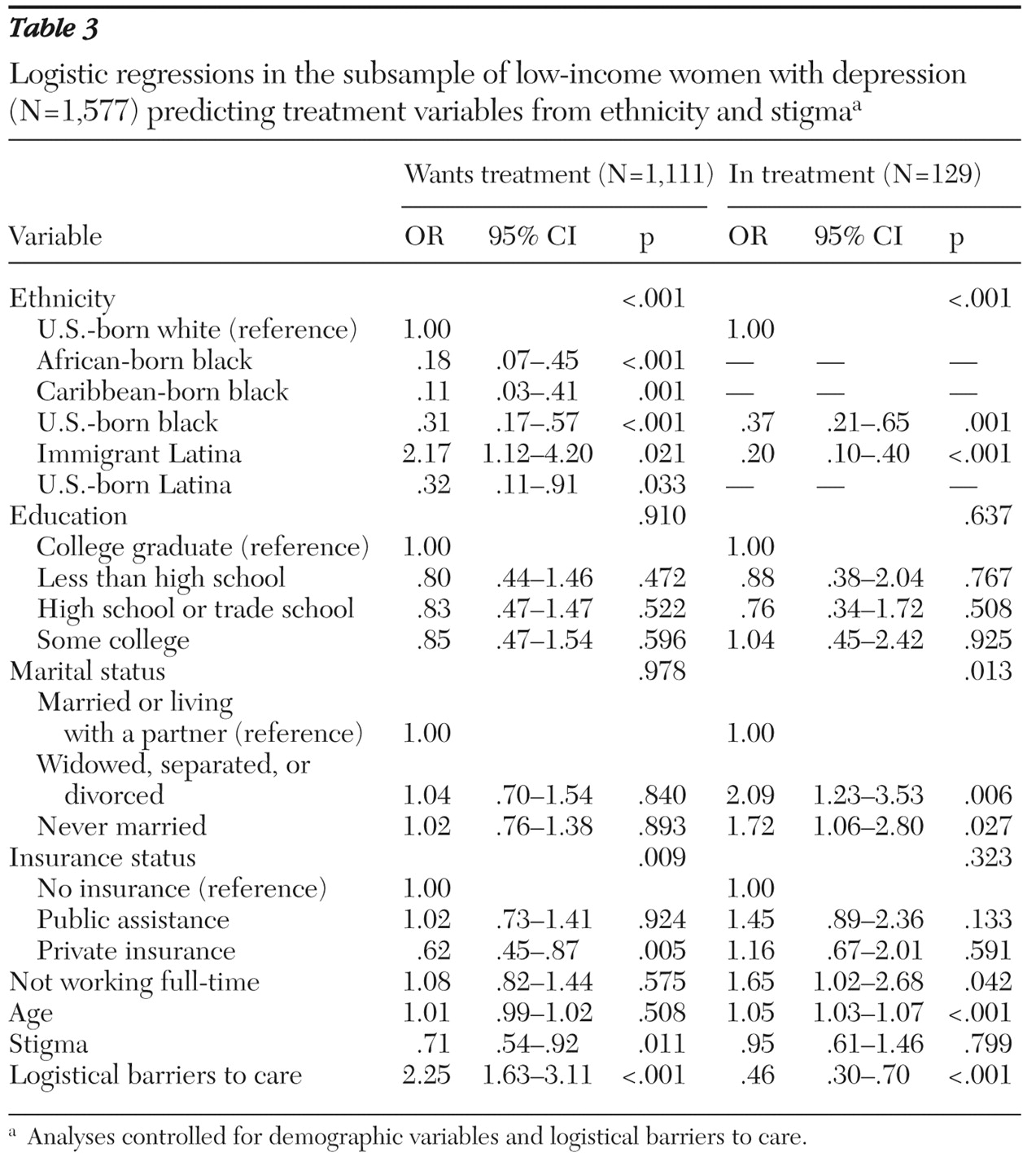

Ethnicity and stigma concerns predicting wanting treatment

Table 3 shows the results of a logistic regression analysis predicting whether wanting treatment was influenced by ethnicity and by stigma, when the analysis controlled for demographic characteristics and logistical barriers to care. Each immigrant and U.S.-born minority group differed from the group of U.S.-born white women. Immigrant African women (OR=.18, p<.001), immigrant Caribbean women (OR=.11, p=.001), U.S.-born Latina women (OR=.32, p=.033), and U.S.-born black women (OR=.31, p=.021) were less likely than U.S.-born whites to want treatment. Conversely, immigrant Latinas (OR=2.17, p=.011) were more likely to want treatment than U.S.-born white women. Women with stigma-related concerns were less likely than those without such concerns to indicate an interest in treatment (OR=.71, p<.05).

Ethnicity and stigma concerns predicting being in treatment

Next, we examined the main effects of ethnicity and stigma on being in treatment, controlling for demographic characteristics and logistical barriers to care. Results are presented in

Table 3, omitting ethnic groups with small samples. There was an overall effect of ethnicity, such that U.S.-born blacks (OR=.37, p=.001) and immigrant Latinas (OR=.20, p<.001) were less likely than U.S.-born whites to be in treatment. Having stigma-related concerns was not a significant predictor of being in treatment.

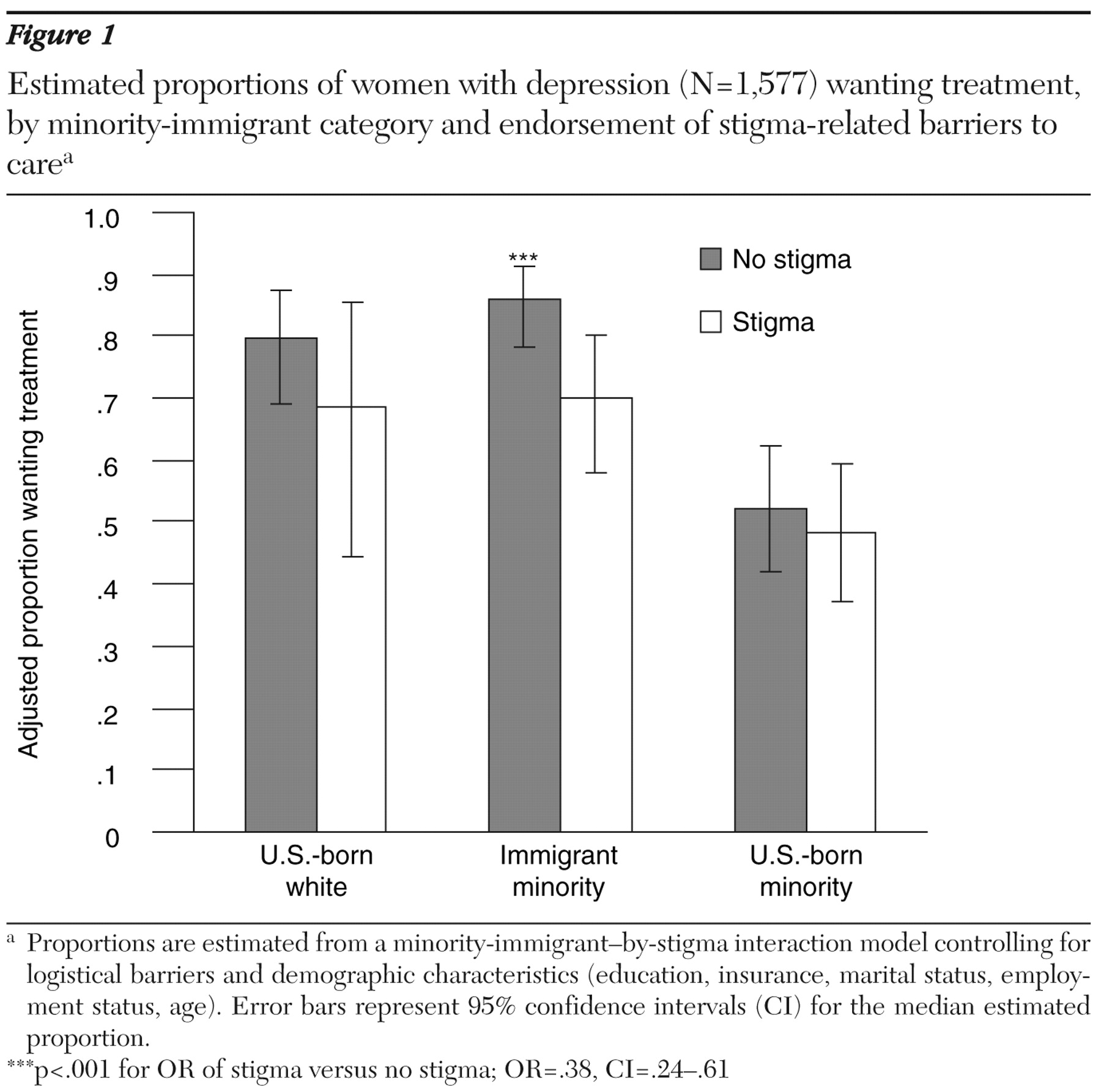

Interactions between minority-immigrant status and stigma

We next ran logistic regression interaction models examining the differential relations between stigma-related concerns and treatment variables between U.S.-born whites, U.S.-born women from ethnic minority groups, and immigrant women from ethnic minority groups, controlling for logistical barriers to care and demographic characteristics. For wanting treatment, there was a significant interaction between stigma concerns and being an immigrant from an ethnic minority group (p<.05). Having stigma concerns was significantly related to lower desire for mental health treatment for immigrant women from ethnic minority groups (OR=.38, p< .001) but not for U.S.-born whites or U.S.-born persons from ethnic minority groups (see

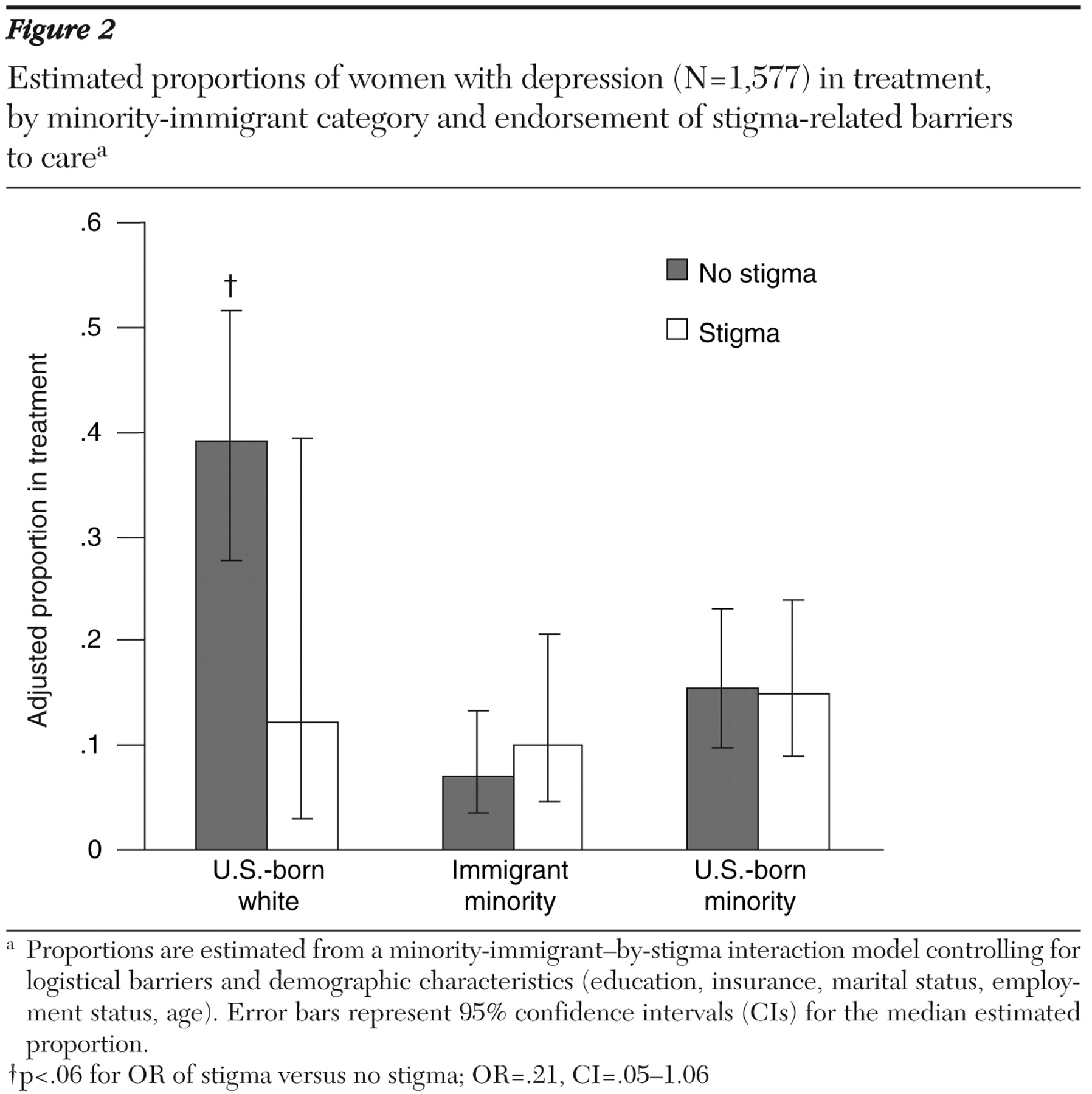

Figure 1 ). There was a trend suggesting a minority-immigrant-status-by-stigma interaction for being in treatment, although this finding was nonsignificant. Stigma concerns were associated with lower rates of treatment among white women, although this finding was not significant (OR=.21, p<.059); there was no significant association among the women from U.S.-born or immigrant minority groups (see

Figure 2 ).

Discussion

Using a large, ethnically diverse sample of low-income immigrant and U.S.-born women from racial and ethnic minority groups, we found that stigma may indeed play an important role in understanding mental health service use by these women. Ethnic differences in stigma were most pronounced among women with depression, with black women, particularly immigrant black women, reporting the most stigma concerns. Among women with depression, compared with U.S.-born white women, immigrant African woman had over three times higher odds and immigrant Caribbean women had over six times higher odds of reporting stigma concerns. Ethnic differences were also evident among women without depression, suggesting broader community-based differences in stigma-related concerns between immigrant black and Latina women and U.S.-born white, Latina, and black women. In the group without depression, compared with U.S.-born white women, the odds of reporting stigma concerns were 26% higher among immigrant Latinas, 39% higher among immigrant African women, and 45% higher among immigrant Caribbean women.

Settings providing care for immigrant women should be alert to the substantial concerns that these women might have about entering mental health care. Client education about mental health treatment, efforts to ensure privacy, and effective stigma-reducing educational campaigns might be helpful for immigrant populations. Further research is needed to explore what accounts for the higher levels of stigma-related concerns in these groups. These differences may reflect general attitudinal differences between the United States and the immigrant women's countries of origin in regard to mental health. For example, evidence from the United Kingdom suggests that black Caribbean women believe that it is inappropriate to discuss personal matters outside the home and that disclosure of mental health problems is considered a sign of moral weakness (

40 ).

Interestingly, among women who are depressed and in need of care, stigma is related to being in treatment for white Americans but not for women from ethnic minority groups. Even among whites, however, the relationship did not reach significance and thus was not robust after considerations of multiple comparisons. Nonetheless, the pattern is suggestive that other barriers to care likely inhibit utilization among low-income women from ethnic minority groups to such an extent that stigma does not have an impact on the already extremely low rates. Our models controlled for insurance and perceived logistical barriers to care. However, other practical barriers may account for the low treatment rates among women from ethnic minority groups and may have prevented detection of more subtle stigma-related effects. In the event that practical barriers to care were no longer impeding persons from ethnic minority groups from getting care, stigma would be more likely to play a role. This interpretation is consistent with research showing greater mental health service use disparities among blacks and whites who were privately insured than among blacks and whites who were uninsured (

41 ).

On the other hand, stigma is more clearly linked to desire for care, an important part of the treatment-seeking process. Among the subsample with depression, stigma concerns were associated with lower rates of wanting care. This association was most pronounced among immigrant women from ethnic minority groups. These patterns could be attributed to the fact that women with depression are faced with the reality of making decisions about whether to seek care, with immigrants having the greatest concerns about stigma. Efforts to eliminate stigma associated with mental health care are likely to result in more women wanting care. It is also possible that characteristics of depression itself may lead women to have more negative views about others and the helpfulness of treatment.

There are also a number of noteworthy racial and ethnic differences in regard to wanting care. Among the subsample with depression, we found that compared with U.S.-born white women, immigrant black women, U.S.-born black women, and U.S.-born Latinas were all less likely to want care. For black women, in particular, this may be because they do not trust the mental health system to treat them fairly (

26,

42,

43 ). Interestingly, immigrant Latinas were more likely than U.S.-born white women to want mental health care. This is in sharp contrast to commonly held assumptions that more "traditional" Latinas are reluctant to seek care, and it is intriguing in light of our finding that immigrant Latinas were among those most likely to report stigma concerns. One possible hypothesis is that they may have felt that our interviewers, who interviewed them in county health settings, were offering them something that they should agree to want. Our clinical experience in providing depression care to this population is that immigrant Latinas may feel that they are being respectful by accepting an offer for help from an interviewer, but they may later experience stigma or other barriers to care and not actually attend the offered treatment.

U.S.-born white women were far more likely to be in treatment than the women from ethnic minority groups. This is not surprising given the extensive literature showing ethnic disparities in mental health care (

2 ). Because women from ethnic minority groups are much more likely to be poor than white women, minority status is often confounded with income inequalities. In this study, most all of the women were poor, and the women from ethnic minority groups were still underserved.

There are limitations to the study presented here. First, the study was correlational, limiting conclusions about the direction of observed effects. Second, the study relied on self-report. Women were asked to think about whether they thought that any of the barriers or concerns would get in the way of their seeking mental health care, which may not reveal all of the subtlety in the treatment-seeking process. Similarly, the study measured perceived stigma in interacting with others and not self-stigma or other aspects of stigma that may have a unique impact on treatment seeking. Third, our study did not specify relations between variables based on countries of origin. Clearly, not all Latino cultures, or all African or Caribbean cultures, are the same. However, research conducted with various Latino cultural groups, for example, reveals similarities in key values, such as reliance on family (

44 ), that influence help-seeking processes. Additionally, our study used immigrant status as the primary method to distinguish between those who had greater or less exposure to mainstream U.S. culture and services systems. However, acculturation and immigration are multifaceted processes, and additional considerations, such as language barriers and acculturative stress, should be considered in future research. Nonetheless, the study presented here is the first of its kind to include a sample as rich in ethnic diversity and to explore differences among immigrant and nonimmigrant women of Latina, African, and Caribbean backgrounds.

Conclusions

Overall, our results indicate that stigma is meaningful in understanding treatment-seeking processes among immigrant and U.S.-born black and Latina women and U.S.-born white women, despite the fact that it was endorsed with lower frequency than logistical barriers to care. Immigrant women were most likely to report stigma-related concerns about care, and depressed immigrant women with stigma concerns were least likely to state that they wanted care. Stigma appears to dampen women's desire to get needed mental health care.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was funded by grants MH-R01-070260 and MH-56864 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Writing of this article was funded through three centers. The Center for Health Improvement of Minority Elderly of the Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research is funded by grant 3P0-3AG-021684 from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health. Drew Project EXPORT of the University of California, Los Angeles, is funded by grant 1P20-MD-00148-01 from the National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health. The UCLA-RAND Center for Research on Quality in Managed Care is funded by grant MH-068639-01 from the National Institute of Mental Health and by funding from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

The authors report no competing interests.