As the duration of inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations has decreased over the past several decades (

1,

2 ), timely follow-up care after hospital discharge has become increasingly important. Individuals who receive timely follow-up care are less likely to be readmitted (

3,

4,

5,

6 ). Those who do not utilize follow-up care services—such as outpatient mental health care, partial hospitalization, and residential treatment—are more likely to be readmitted (

7,

8 ). As a result, timely care after psychiatric hospitalization is one of the behavioral health quality measures in the widely used National Committee for Quality Assurance's Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS) (

9 ), and a number of states have prioritized efforts to improve timely follow-up care after psychiatric hospital discharge (

10,

11,

12,

13 ).

Multiple studies have examined who is at greatest risk of not receiving timely follow-up care, and a range of predictors has been identified, including diagnosis, treatment history, and linkages with community mental health care before hospitalization (

3 ). For example, in a single-site hospital study that included primarily publicly insured individuals, follow-up care after inpatient hospitalization was less likely for individuals with serious mental illness who were admitted involuntarily and had no history of hospitalization in a public facility (

14 ). A population-based study of commercially insured individuals found that having a prior relationship with a mental health provider and being diagnosed as having an affective disorder were associated with higher rates of timely follow-up care (

4 ). A study of individuals in Veterans Affairs hospitals found higher rates of follow-up care for individuals diagnosed as having posttraumatic stress disorder than for those diagnosed as having schizophrenia or major affective disorders (

15 ). In a study of individuals in managed Medicare, African Americans were less likely than Caucasians to receive follow-up care, and there was also a positive association between length of inpatient stay and rate of follow-up care (

16 ).

Despite the fact that Medicaid-enrolled individuals have a greater prevalence of serious psychiatric disorders and greater utilization of intensive mental health services, compared with other populations (

17 ), we are unaware of population-level studies that have examined predictors of timely follow-up care after inpatient care for the Medicaid-enrolled population. To better understand predictors of timely follow-up care among Medicaid-enrolled individuals and to determine whether predictors are comparable with those of individuals not enrolled in Medicaid, this study explored factors associated with timely follow-up care among Medicaid-enrolled adults. We also examined whether there is significant variation in rates of follow-up care by discharging hospital after controlling for patient characteristics. Given the findings in studies of non-Medicaid populations, we hypothesized that higher rates of follow-up care would be seen among Caucasians, individuals who had had mental health treatment before inpatient hospitalization, individuals voluntarily admitted to the hospital, and individuals who had longer inpatient stays.

Results

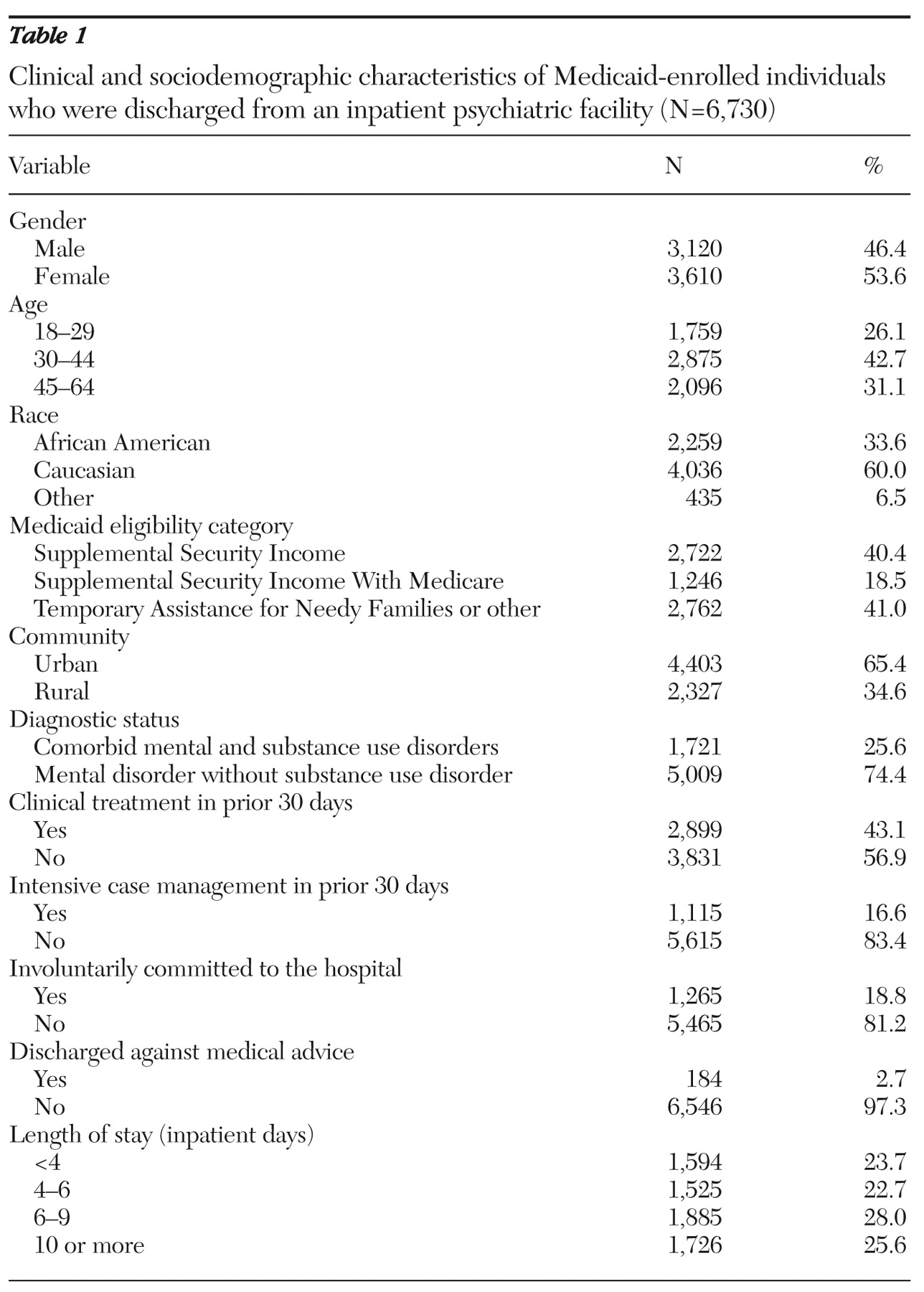

We identified 6,730 Medicaid-enrolled adults who had at least one psychiatric hospitalization during calendar years 2004 or 2005. Fifty-four percent of these individuals were women, and 34% were African American. Twenty-six percent had been identified as having a comorbid substance use disorder. More information about the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the population are presented in

Table 1 .

Approximately one-third (N=2,037, 30%) of hospitalized adults had follow-up behavioral health specialty care within seven days of discharge; 49% (N=3,280) had such follow-up care within 30 days. Of individuals receiving follow-up care within 30 days, outpatient mental health services were the most common initial follow-up care received by individuals (N=1,775, 54%). Twenty percent of individuals (N=670) initially had a medication management visit as follow-up care, 12% (N=391) first received follow-up care at a partial hospital, 10% (N=314) first received outpatient substance abuse treatment, and 4% (N=115) were first seen by an assertive community treatment team.

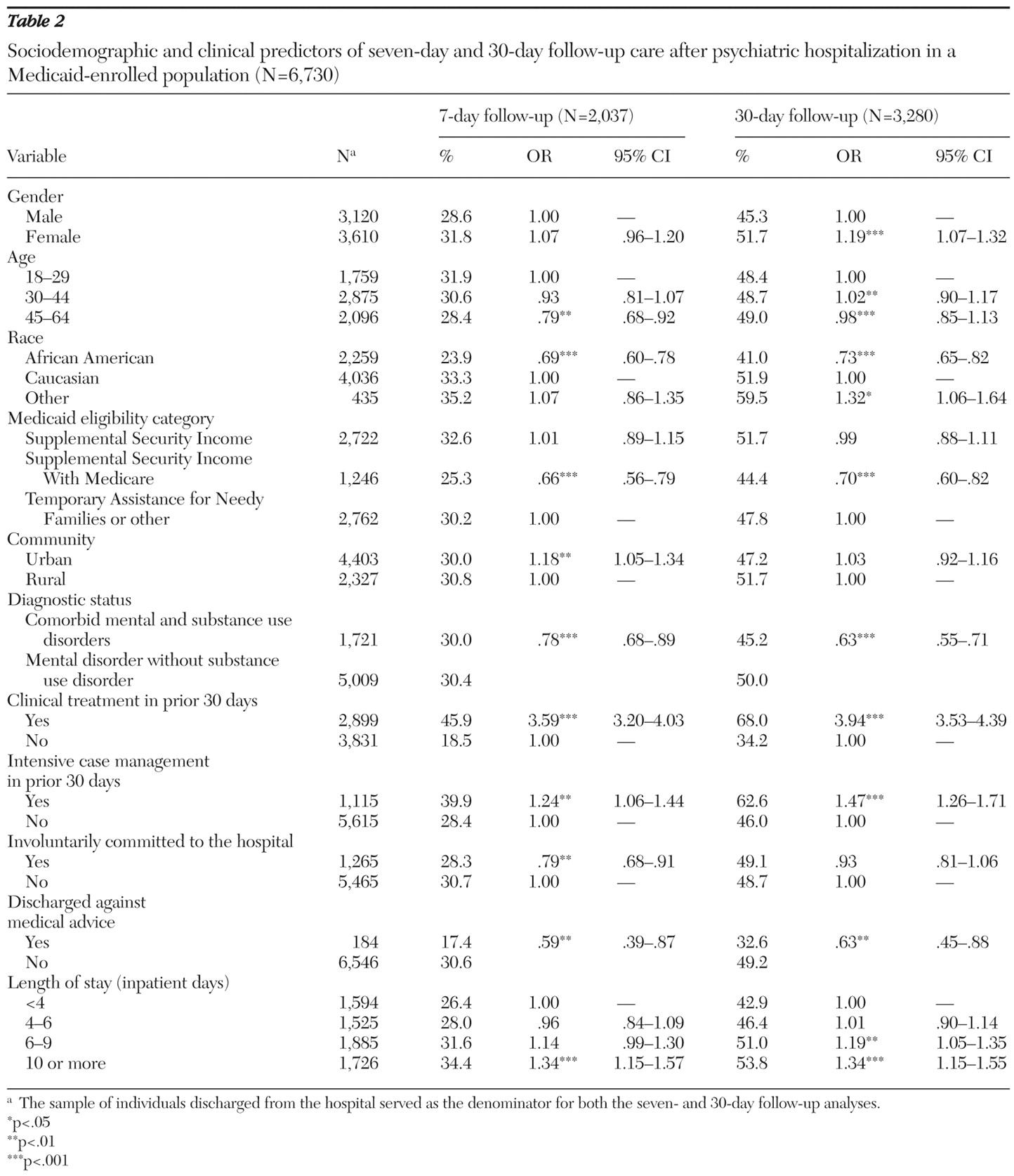

The strongest predictor of seven- or 30-day follow-up care was receiving clinical treatment in the month before admission. Individuals who had been in treatment were over three times as likely to receive follow-up care within seven days of discharge, and almost four times as likely to receive follow-up care within 30 days of discharge (

Table 2 ). Individuals who had received case management services in the month before admission were also significantly more likely to receive follow-up care within seven days and within 30 days than were individuals whose hospitalization exceeded nine days. African Americans, persons who were discharged against medical advice, those with a comorbid substance use disorder, or those who were enrolled in SSIM were significantly less likely than other individuals to receive seven- or 30-day follow-up care (

Table 2 ). We also found that individuals living in rural areas and those involuntarily admitted to the hospital were less likely than others to have follow-up care within seven days, but we found that these differences disappeared by 30 days (

Table 2 ).

In examining the relationship between discharging hospital and timely follow-up care, controlling for individuals' sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, we found that discharging hospitals were significantly associated with rates of seven-day follow-up care (Wald χ 2 =8.61; df=1, p< .01), but there was not a significant association with rates of 30-day follow-up care. When the analysis controlled for individual characteristics, the OR for seven-day follow-up care differed threefold between the top-performing discharging hospital, for which 45% of discharged individuals received follow-up care within seven days (OR=1.68, 95% CI=1.22–2.33), and the lowest-performing discharging hospital, for which 23% of discharged individuals received follow-up care within seven days (OR=.47, 95% CI=.30–.76).

Discussion

We found that almost 30% of Medicaid-enrolled adults received follow-up care within seven days of discharge from psychiatric hospitalization and that within 30 days of discharge, 49% of individuals had at least one follow-up visit. Better understanding of predictors of timely follow-up care will allow better targeted interventions designed to improve rates of timely follow-up care. Because such follow-up care has been shown to be associated with lower rates of readmissions in several studies (

3,

7,

8 ), such targeted interventions have the potential of enhancing the continuity of care and reducing unnecessary hospital readmissions.

There have been few studies of predictors of follow-up care after psychiatric hospitalization in publicly insured populations. Methodological differences in qualifying follow-up services and population eligibility make direct comparisons of findings in these studies and the more widely available HEDIS numbers difficult. For example, the HEDIS rates of seven-day follow-up care for the Medicaid population included in our analyses ranged from 43% to 51% (greater than our 30% follow-up rate). This is somewhat higher than the national average (39%) for Medicaid plans reporting HEDIS data (

22 ). Moreover, the HEDIS rate for seven-day follow-up care for our population exceeds the 39% reported by health plans for individuals in Medicare, but it is lower than the 56% HEDIS rate reported by commercial health plans. Although HEDIS rates provide a useful point of comparison across reporting health plans, clinicians and policy makers may find that more refined approaches to calculating follow-up rates (for example, separating children and adolescents from adults) are more useful in targeting the interventions.

Individuals in mental health treatment before hospitalization have been shown to be more likely to receive follow-up care (

4 ). We also found that rates of follow-up care at seven days were substantially higher for individuals in treatment before hospitalization (46%) than they were for individuals who had not been in treatment (18%). In fact, after the analyses controlled for other factors, individuals in treatment before hospitalization were three to four times more likely to have timely follow-up care than individuals who were not in treatment. The magnitude of this difference is substantially greater than for the other factors that we were able to examine and suggests that individuals who are not in treatment before psychiatric hospitalization may require unique and novel strategies to successfully enhance the likelihood of their receiving timely follow-up care.

Others have found that individuals with co-occurring substance use disorders are at risk of poor rates of follow-up care after discharge from inpatient hospitalization (

23 ). Engaging and retaining individuals with co-occurring disorders in follow-up care can be challenging (

23,

24 ), and individuals with such disorders may be at higher risk of readmission because they have not received timely follow-up care (

25 ). The difficulties in providing high-quality care for individuals with comorbid mental health and substance use disorders may be exacerbated by fragmentation and poor coordination between the substance abuse and mental health care delivery systems. Thus experts have called for greater integration of mental health and substance abuse care to improve the quality of behavioral health care for such individuals (

26,

27 ).

Individuals in rural communities were significantly less likely than those in more urban communities to receive follow-up care within seven days, but the difference between these two groups did not remain at 30 days. This difference suggests that individuals in rural areas may have greater difficulty in seeing a provider right away for follow-up care but that they can be accommodated within several weeks. Studies of behavioral health services in rural areas have repeatedly documented an insufficient mental health workforce and difficulty in accessing mental health services (

28,

29,

30 ). Special efforts may be necessary in rural areas to facilitate access for individuals who need to receive follow-up care immediately after hospital discharge.

Consistent with our results, other studies have found lower rates of follow-up care among individuals involuntarily admitted to the hospital (

14 ). We also found that individuals discharged against medical advice were less likely to have timely follow-up care, possibly because they did not receive adequate and appropriate discharge planning or because optimal aftercare arrangements were not developed. Individuals involuntarily admitted to the hospital and those discharged against medical advice may be substantially less committed than other individuals to receiving mental health follow-up care, and they might be particularly appropriate candidates for programs that seek to enhance individual motivation for mental health care. Such programs have been shown to be effective in increasing engagement and retention in other populations (

31,

32,

33,

34,

35 ).

Numerous studies have documented disparities in the access to and quality of behavioral health care received by African Americans (

36,

37,

38,

39 ), including lower rates of seven- and 30-day follow-up care (

16 ). Despite increased attention to racial and ethnic disparities in behavioral health care and efforts to reduce these disparities in recent years (

40 ), we found significantly lower rates of seven- and 30-day follow-up care among African Americans than in other racial or ethnic groups. Efforts to enhance rates of follow-up care among African Americans might consider addressing the cultural competency of both inpatient and outpatient providers (

41,

42,

43 ), as well as other factors, such as perceived clinician empathy, which appear to influence whether individuals seek follow-up care (

44 ).

We also found dramatic differences in the follow-up rates among discharging hospitals, after controlling for individual-level characteristics. Provider-level variation has been used to identify opportunities to improve the quality of health care services in other areas of health care (

45,

46 ). States, payers, consumers, and others have previously used such information to improve care by providing feedback to providers about performance on a variety of metrics (

47,

48,

49 ), as well as to help identify providers or organizations that have developed novel and successful processes to improve care (

50 ). Such approaches may also be useful in improving the behavioral health care received by individuals with mental health and substance use disorders, although the greatest impact will likely require efforts beyond simple publication of the data (

51 ). Specifically, the approach to and quality of a hospital's discharge planning may be critically important in achieving improvements in the rates of follow-up care (

14,

31 ). Creative and aggressive approaches to such planning may be particularly critical for individuals with shorter hospitalizations—that is, individuals for whom we and others (

52 ) have found lower rates of timely follow-up care and for whom there may be insufficient time in the hospital for more traditional approaches to discharge planning.

Our findings must be viewed within the context of several limitations. Our study relied primarily on administrative data. We do not know how these data correlate with patient report and medical chart abstraction data. However, Medicaid claims are subject to audit as well as edits to identify erroneous or incomplete claims at the time of submission, and published studies of the validity of Medicaid claims data have found generally high rates of agreement between medical records and claims data for both behavioral health patients (

53,

54 ) and physical health patients (

55 ). Claims data also do not provide rich clinical and contextual information, such as information about socioeconomic status and other environmental factors (for example, homelessness) that are likely to be associated with follow-up rates. However, there is likely less variation in socioeconomic status among Medicaid-enrolled individuals than there is in other populations for which claims data analyses are reported, such as individuals with Medicare, commercially insured individuals, and individuals in the Department of Veterans Affairs system.

For dual-eligible Medicaid and Medicare individuals (SSIM), we may be underestimating follow-up rates, because we cannot observe services for which the provider has submitted a claim only to Medicare. Similarly, using prior claims related to substance abuse is likely to substantially underestimate the prevalence of individuals with substantial substance use disorders (

56 ). We also did not observe services for which no claim is submitted (for example, services provided under county block grant funds, funded by charities, or for which a provider does not submit a bill), but the provision of such services is negligible in the communities in which these individuals live.

We do not know whether our findings generalize to regions where care is managed differently or where behavioral health care services for Medicaid-enrolled individuals are unmanaged; rates of follow-up care might be lower if care is unmanaged (

57 ). We examined only the first inpatient admission during the selected time period and restricted our sample to adults, limiting our ability to compare our results with the National Committee for Quality Assurance's HEDIS quality indicators (

58 ). We excluded from our analysis individuals readmitted within 30 days; we do not know how their inclusion might have changed the results, but we anticipate that such individuals might be less likely to have timely follow-up care. We also have no information on the quality or clinical appropriateness of claimed services.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, better understanding of the factors associated with follow-up care among Medicaid-enrolled individuals will allow more targeted efforts to improve the continuity of care for many individuals. With the increasing use of electronic health records and comparable information technology systems in hospitals and clinical provider organizations, future research endeavors in which administrative data are linked with more robust clinical and program data will facilitate a better understanding of the factors driving utilization patterns.

With respect to interventions, prior efforts to improve follow-up rates suggest that no one approach is likely to be effective for all individuals, and our findings indicate that multiple factors, including individual characteristics, prior experiences with the behavioral health system, available outpatient treatment resources, and the discharge planning process used by discharging hospitals, may all contribute to current rates of timely follow-up care. Therefore, successful efforts will likely require multiple strategies with different approaches to improving follow-up rates and close monitoring among selected high-risk populations. These efforts may involve interventions that occur before discharge from the hospital, such as enhanced efforts to set appropriate expectations for outpatient treatment and increased attention of inpatient staff to an individual's preferences with respect to outpatient provider (

59,

60 ), efforts to reduce waiting lists to allow for more timely visits after discharge (

3 ), enhancing predischarge contact between individuals who are hospitalized and outpatient providers (

61 ), and enhancing communication between inpatient and outpatient clinicians.

System-level interventions, such as home-based visits and more aggressive case management (

62 ), must also be considered. The development, implementation, and rigorous evaluation of feasible, acceptable, and sustainable interventions to enhance timely follow-up and subsequent engagement that build upon the existing knowledge base are sorely needed, as is the dissemination of effective practices—once these practices are identified. Because many individuals are likely to seek follow-up care from providers other than the ones to which they were referred (

3 ), successful efforts to improve the rates of follow-up care will almost certainly require an integrated effort to implement effective practices across a range of individuals and organizations, all of whom can make an important contribution to improving the behavioral health care of consumers.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Support for this study was provided by grant 5-P30-MH-030915-28 from the National Institute of Mental Health and the Community Care Behavioral Health Organization. The authors are indebted to Allison Guaspari, B.S., Karen Celedonia, B.S., Samantha Shugarman, M.S., and Stephanie Lonsinger, B.S., for research assistance and assistance with the preparation of the manuscript and to Susan Essock, Ph.D., Stephanie Fudurich, R.N., M.B.A., Deborah Wasilchak, M.A., Michael Jeffrey, M.S.W., Emily Heberlein, M.S., Lydia Singley, M.S.W., Kim Falk, B.S., Pat Valentine, M.S., and the consumers, providers, and other members of the Community Care's Quality Care and Management Committee for feedback on this article.

The authors report no competing interests.