After the surge in incarceration during the past 30 years, an increasing number of individuals are now being released from prison, estimated to be up to 600,000 to 750,000 per year (

1,

2,

3,

4 ). The estimates indicate that as many as 100,000 consumers of mental health services are returning to the community each year (

4,

5 ). These individuals often have co-occurring substance use problems and are more likely than other mental health service consumers to be poor and nonwhite (

5,

6,

7 ).

Like their counterparts released from psychiatric hospitals, persons with mental illness released from prison reenter the community with many needs (

4 ). Family and friends are often expected to facilitate reentry by providing housing, financial assistance, transportation, and personal support (

8,

9,

10 ). Although it is customary for people leaving hospitals to have discharge plans that coordinate these supports with treatment, this is rarely the case for those leaving prison. Individuals typically leave prison without a reentry plan, except possibly a parole supervision condition. They enter an extreme life transition in which there are few, if any, rehabilitative resources for former prisoners, much less for those with behavioral health needs (

11,

12,

13,

14 ). What is done by, for, and with these individuals under such stress can make the difference between a new life and a return to the old life at a greater risk for a new arrest.

Critical time intervention (CTI), a focused, time-limited intervention to build community connections to needed resources, has been shown to be effective for consumers making a transition to community housing after discharge from an institution (

15,

16,

17,

18 ). This article proposes CTI as a promising model for enhancing support during the reentry process of prisoners with severe mental health problems and presents a conceptual framework for evaluating its effectiveness in this context.

The CTI model

CTI is a nine-month, three-stage intervention that strategically develops individualized linkages in the community and seeks to enhance engagement with treatment and community supports through building problem-solving skills, motivational coaching, and advocacy with community agencies. CTI workers can increase the number and strength of clients' ties to community resources, especially ties to behavioral health providers and other service providers. Although originally used with persons who were transitioning from homeless shelters to housing in the community, CTI has now been adapted for those leaving psychiatric hospitals. Its application to homeless families was featured in the President's New Freedom Commission Report (

19 ), and the model is one of a handful of homelessness prevention interventions recognized in the National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Policies of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

CTI was first developed and tested in a randomized trial for people with mental illness who were moving into housing from New York City's Fort Washington Armory shelter (

15,

16 ). In that trial, persons who received CTI experienced fewer nights homeless during an 18-month follow-up period than those who received the usual case management services. One notable finding from this study was the durability of the effect; improved outcomes were sustained even after termination of the intervention after nine months (

16 ). CTI has demonstrated cost-effectiveness for addressing homelessness (

18 ). In the United States CTI has since been used with homeless families leaving shelters (

20 ), men and women after discharge from inpatient psychiatric treatment (

21,

22 ), and homeless women with co-occurring disorders who were moving from a shelter into housing (

23 ). In addition, studies of CTI for people leaving prison in the United Kingdom have recently begun (

24 ).

The CTI intervention has two components. The first is to strengthen the individual's long-term ties to services, family, and friends. To whatever degree these supports are available, individuals with mental illness and those upon whom they depend often need assistance to work together. Moreover, many consumers have preferences for treatment that may not easily link with preferences of providers, landlords, friends, and families. CTI attempts to promote treatment engagement through psychosocial skill building and motivational coaching.

The second component of CTI is to provide emotional and practical support and advocacy during the critical time of transition. During a stay in an institution, an individual may develop strong ties to the institution and become habituated to having therapeutic and basic needs met on site. These individuals often return to an isolated life in the community. For this reason, CTI provides temporary support to the client as he or she rebuilds community living skills, while working with the client to develop a persisting network of community ties that will support long-term recovery and reintegration into the community.

CTI is not intended to become a permanent support system; rather it ensures support for nine months while the person gets established in the community. CTI workers are singularly focused on developing a support system that lasts, and most important, that fits the individual and the community to which the individual returns. Thus, in many ways, the robust element of the intervention is building a resilient network of community supports that continues after CTI ends.

The foundation of CTI rests on elements found in other evidenced-based models. The core elements include small caseloads, active community outreach, individualized case management plans, psychosocial skill building, and motivational coaching. The overall framework borrows from assertive community treatment models and training in community living (

25,

26 ), which introduced an approach with these common elements and which has been rigorously tested over the past 30 years (

27,

28 ). The community treatment strategies of CTI are also grounded in the evidence base for psychiatric treatment, substance abuse treatment, and psychosocial interventions. These interventions include elements of assertive outreach, illness management (

29 ), motivational interviewing, chronic disease management, and integrated substance abuse treatment (

30,

31,

32,

33 ). All of these interventions have been tested by experience and empirical investigation and have been found to improve outcomes.

From aftercare planning to reentry planning

In mental health services, the success of aftercare planning depends on the quality of personal and community connections. For people with mental illness, smaller, less diversified social networks are associated with higher rates of rehospitalization and unsatisfactory treatment outcomes (

23,

34,

35,

36 ). Tensions around adherence to medication regimens and periods of social isolation and antisocial behavior may strain relations with friends, family members, and professional providers (

6,

9,

10 ). Co-occurring substance abuse can fracture prosocial ties and also support the formation of other social ties centered on substance abuse (

37 ).

Reentry planning for persons with mental illness after incarceration is the counterpart to discharge planning for persons being discharged from a psychiatric institution. It aims to set in place a strategy for connecting individuals to housing, employment, and education and creating positive social ties to reinforce these connections. Ideally, reentry planning capitalizes on existing social connections, intervenes to preserve connections on the outside while a person is incarcerated, and builds new community connections (

4 ). In practice, reentry planning is often no more than a new buzzword for loosely brokered services with few strategies for access to effective treatment or other supports (

14,

38,

39 ). Typically, criminal justice agencies are the major provider of reentry services for former prisoners with mental illness (

40 ). The mental health system has offered no comprehensive evidence-based models for this transition other than forensic assertive community treatment, an adaptation of assertive community treatment applied to prison release settings (

41 ). A broader range of reentry models is needed for interventions that are driven by priorities of the mental health system in the context of the criminal justice process.

Although at a conceptual level CTI seems to apply well to the process of prisoner reentry, there are also key differences between prison release and discharge from a hospital or shelter that must be considered. For instance, the availability of basic postdischarge resources, such as housing, is likely to be constrained by probation, parole, or other criminal justice system factors. Also, although a shelter or hospital resident may make prerelease visits to potential housing and other community settings, prisoners typically cannot leave prison to help plan their life after reentry.

Co-occurring substance use disorders

Research shows that compared with persons who have single disorders, those with co-occurring diagnoses are more debilitated by their illnesses (

42 ), have lower functioning capacity (

43,

44,

45 ), are heavier users of expensive services (

46 ), and are less likely to adhere to treatment expectations (

47,

48 ); they also have less desirable treatment outcomes (

45,

49,

50,

51 ). They have greater risk of involvement in the criminal justice system (

52 ). The rate of co-occurring substance abuse among people with mental illness in the criminal justice system is substantial; approximately two-thirds of state prisoners with mental illness report being under the influence of alcohol or drugs at the time of their offense (

5 ).

Blended service models, which integrate mental health and addiction services into a unified care approach, and specialized case management strategies that address situational barriers to care are among the innovative strategies developed to improve engagement and promote more positive client outcomes. The effectiveness of blended treatment is supported by a growing body of research, which has led SAMHSA and the National Institute on Drug Abuse to recognize it as a best practice for this population in both inpatient and outpatient care as well as for those involved with the criminal justice system (

31,

53,

54 ). Further, the evidence supports active, outreach-oriented, flexible, individualized interventions that attempt to establish a safe and supportive environment for community living, including housing, work, and social relations (

30,

55,

56 ). Such interventions include supervision by a psychiatrist trained in the treatment of co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorders and ongoing attention to relapse prevention and maintenance of motivation (

30,

55,

56 ). One approach to integrated treatment that has been tested in conjunction with CTI is dual recovery therapy (DRT) (

30,

55,

57,

58 ). DRT supports case managers in using evidence-based substance abuse treatment therapies. It is a manualized set of structured group sessions combined with ongoing support of case managers to enhance motivation to engage in substance abuse treatment (

59,

61,

62 ).

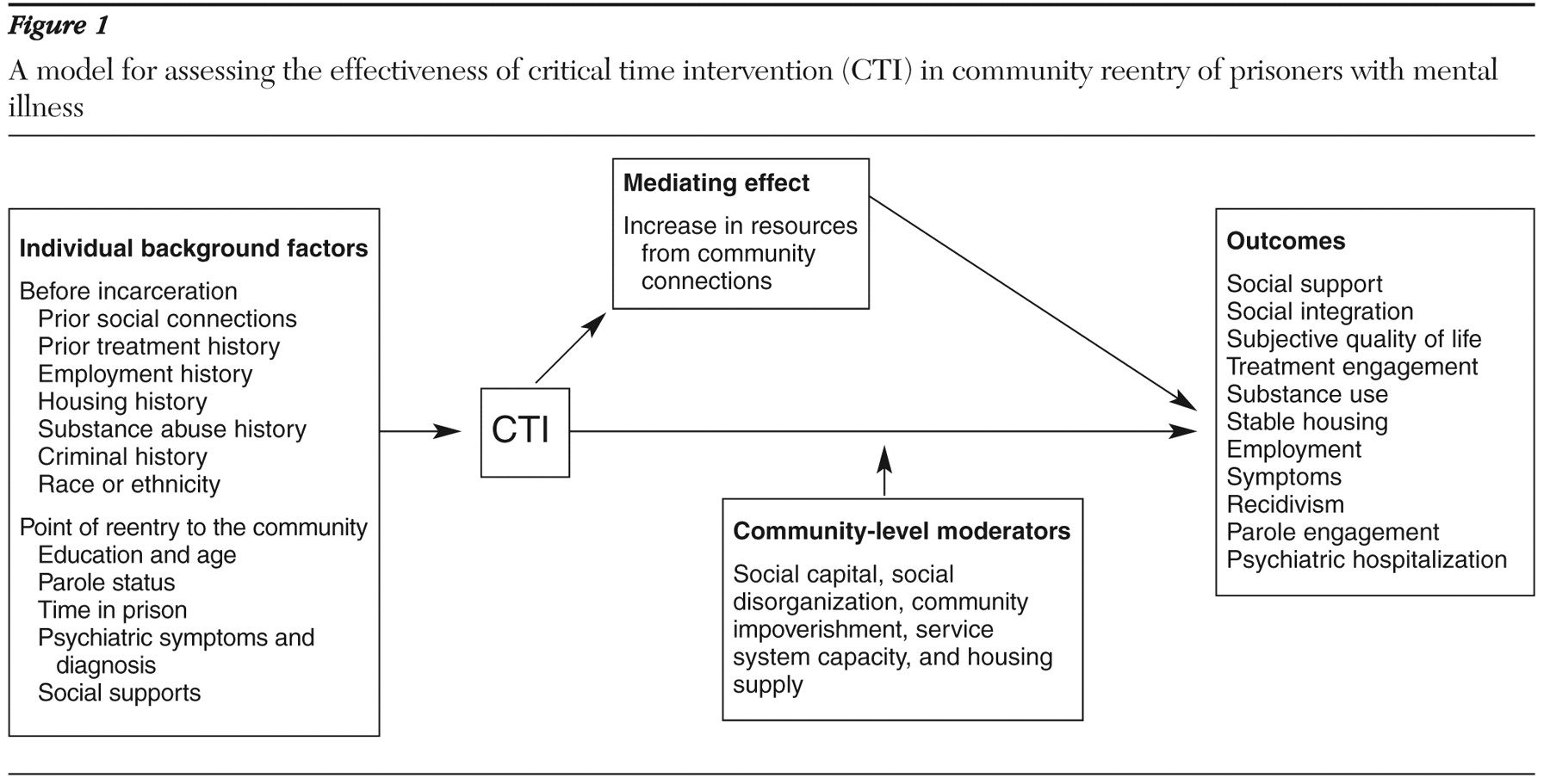

A conceptual framework to assess effectiveness

Only one randomized trial testing the effectiveness of CTI with persons with mental illness reentering the community from incarceration is currently being implemented. (For more information on this trial contact the first author.) This article presents a conceptual model from that trial of CTI effectiveness in reentry that combines an understanding of mental health outcomes and criminal justice outcomes (

Figure 1 ). The model addresses prisoner reentry as it applies to people with mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders. It emphasizes the role of community ties in individual and social outcomes.

In the model the CTI intervention is positioned as a connector between prison and community. Growth in community ties mediates the effect of CTI on consumer outcomes. This mediator represents a growth in social capital, conceptualized at the individual level (

63,

64 ). The model also includes community-level factors (

64,

65 ) that are included as potential moderators. Therefore, in addition to providing a framework for testing the effectiveness of the CTI intervention on mental health outcomes, we provide a theoretical framework for testing individual and community mechanisms that have an impact on outcome in reentry.

A key element in this model is the mediating effect of increases in resources that are embedded in social relationships. This is the "sticky" mechanism for CTI effectiveness that helps sustain the impact after the intervention is over. However, little research supports the effectiveness of interventions in increasing community connections. Research on the activities of CTI workers can develop this literature by documenting the effectiveness of this mechanism in regard to consumer outcomes in general, not just for prisoner reentry.

Housing is the single most critical need for persons with mental illness after discharge from any institutional stay, and it is often the most difficult need to meet. Housing for prisoners, ostensibly homeless at release, is often tenuously connected to social relationships. More reliable housing arrangements are frequently linked to formal services. Access to and continued tenure in housing may rely in part on the strength of the connection between the individual returning from prison and service providers (

39 ).

Community impoverishment has been shown to explain involvement in the criminal justice system and prosocial outcomes among people in urban communities (

66,

67 ) Therefore, community-level factors are proposed in this model as a moderator. However, testing this effect in a randomized field trial setting may be challenged by limited variance in neighborhood-level variables for the neighborhoods involved, most of which are expected to be low in prosocial, legal economic options in terms of employment, housing, and daily activities.

Conclusions

Much work remains to be done toward developing and testing a variety of effective models to facilitate community reentry of persons with mental illness from different types of correctional facilities. The seven million to ten million persons who will be discharged from local jails in the United States each year is ten times the largest estimate of the number of persons leaving prisons (

68 ). Prisons and jails represent different populations of individuals returning from incarceration and operate under different organizational constraints. They thus present unique challenges in implementing effective reentry strategies.

Among collaborative mental health and criminal justice interventions, the most impressive results to date have been obtained from interventions that rely on assertive community treatment, sometimes in a time-limited format, as the primary driver of consumer-level outcome (

40,

41,

69,

70 ). CTI presents an alternative that is specifically structured to build mental health system capacity to facilitate transitions, establish connections for reentering clients, and allow the connections to work. Principally founded on the values of the public mental health system, the goals of CTI are to connect consumers with sustainable formal and informal relationships in the community. CTI differs from most reentry programs that are initiated by the justice system (

40 ) in its focus on the well-being of the consumer as a value at least on par with public safety. Hopefully, this approach will lead to reduced recidivism and reduced involvement in the criminal justice system among people with mental illness.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Support was provided by grant R01-MH-076068 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), from the Center for Mental Health Services and Criminal Justice Research (funded by NIMH grant P20-MH-068170), and from the Center for Homelessness Prevention Studies (funded by NIMH grant P30-MH-071430). The authors express their gratitude to Nancy Wolff, Ph.D., and Steven Marcus, Ph.D., for their comments and suggestions.

The authors report no competing interests.