Although the evidence base is tentative, several studies suggest that payee programs offered within clinical settings confer secondary benefits in the form of reductions in hospitalization (

3 ) and homelessness (

5 ). Payeeship also has been linked to improved functioning in the areas of substance abuse, treatment adherence, and quality of life (

1,

6,

7 ). Recent research, however, also highlights several potential downsides to payee arrangements.

Most notable, studies suggest that payeeship is sometimes associated with negative interactions between clients and payees (

6,

8,

9,

10,

11 ); in particular, potential strain to the therapeutic alliance has been cited as a concern (

1,

6,

10 ). Only one previous study, however, has directly assessed the effects of payeeship on the client-provider relationship (

12 ). That study assessed whether clients assessed the alliance with their nonclinician payees as weaker than their alliances with their primary clinicians. No such differences were found, but because the sample studied was relatively small and did not include in the comparison clients without payees, clarification of this issue is needed.

Previous research implies that strain on the alliance stems from conflict between clients and payees over the payee's power to control money disbursement (

6,

10,

11 ). Such tensions may be aggravated when payeeship is used strategically as a source of treatment leverage. That is, payees sometimes promote treatment adherence by making the receipt of funds contingent on appointment attendance, taking medication, or abstinence from drug or alcohol use (

13,

14,

15 ). Thus payeeship could be viewed as an opportunity for the use of therapeutic social control or influence (

16 ), or what has also been termed therapeutic limit setting (

17 ). Although use of payeeship as leverage to promote treatment adherence is apparently somewhat common (

13,

14 ), recent studies show that this practice is associated with experiences of coercion and lowered autonomy (

18 ) and that the practice is generally opposed by consumers (

19 ).

In this study, we asked two questions. First, does having a clinician as a payee affect the case management relationship negatively? And second, if so, is the effect mediated by whether the payeeship arrangement is used as a source of financial leverage? The survey reported here assessed the prevalence of treatment pressures experienced by adults in public mental health services. To assess the effects of financial pressures on the treatment alliance, we used a recently developed measure of the client-provider relationship tailored specifically to the context of intensive service delivery to people with serious mental illness (

20 ), which takes into account unique features of the case management relationship, including the potential for disagreement, conflict, and struggle (

21,

22,

23,

24 ), which may be particularly salient in the context of clinician payeeship.

Results

About half of the sample (107 of 201, or 53%) reported having a payee or money manager; among those with payees, most (84 of 107, or 79%) reported that this individual was a mental health professional. The remainder of respondents with a payee (23 of 107, or 21%) reported that a family member or other informal network member (such as a friend or minister) served in this role. Because our primary focus pertained to differences between clinician payee arrangements and all other arrangements (family or friend payee and no payee), we used bivariate statistical tests (chi square for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables) to compare respondents with a clinician payee versus all others (

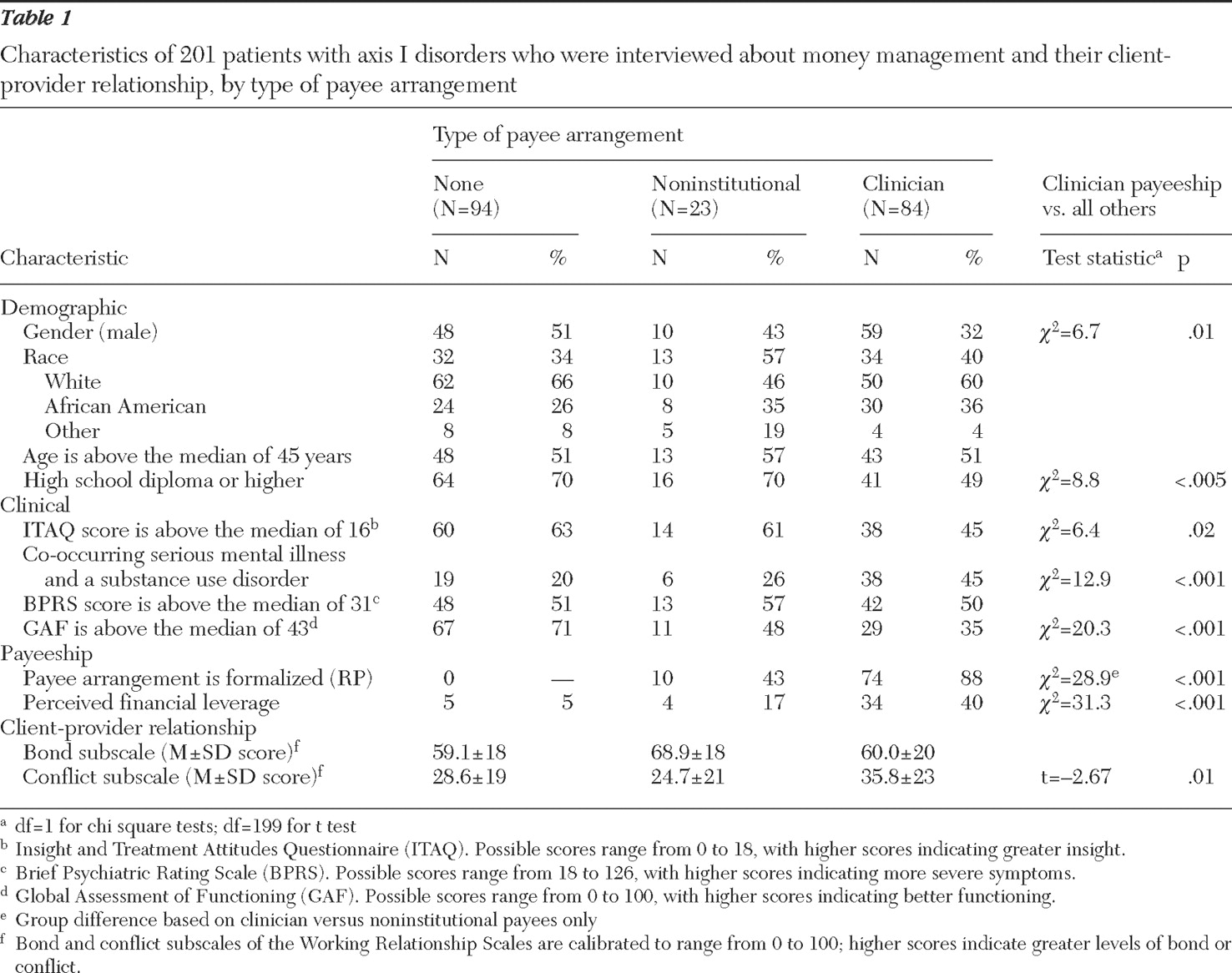

Table 1 ).

Relative to noninstitutional payeeships, clinician payee arrangements were more likely to be assigned through the representative payee program, which often signifies an involuntary arrangement (

1 ). Compared with other respondents, persons with clinician payees were more often male and were more likely to have co-occurring disorders. They also were rated as having lower functioning, they reported less insight into their mental illness, and they were less likely to complete high school. These results suggest that the participants with clinician payees were more severely impaired than those with no payee or a noninstitutional payee.

About one-fifth (43 respondents) of the 201 respondents reported recent experiences of perceived financial leverage. Of those who did so, most (34 of 43, or 79%) had clinician payees as opposed to no payee or a noninstitutional payee ( χ 2 =31.3, df=1, p<.001). In fact, 34 of 84 respondents (40%) who reported having a mental health clinician as their payee reported that they perceived that their money would be withheld if they did not adhere to treatment.

Respondents with clinician payees also scored significantly higher on the conflict dimension of the client-provider relationship, indicating that they were more likely to experience hostile, intrusive, or negative interactions with the case manager. Scores on the bond dimension, however, did not vary significantly between respondents with clinician payees and all other respondents (those with no payee or a noninstitutional payee). Thus the bivariate analyses suggest that in comparison with respondents with no payee or a noninstitutional payee, respondents with clinician payees were more disabled, were more likely to experience perceived financial leverage, and reported higher levels of conflict and negativity in their relationships with their case managers. Subsequent analyses aimed to further clarify the relationships between having a clinician payee, financial leverage, and the client-provider relationship.

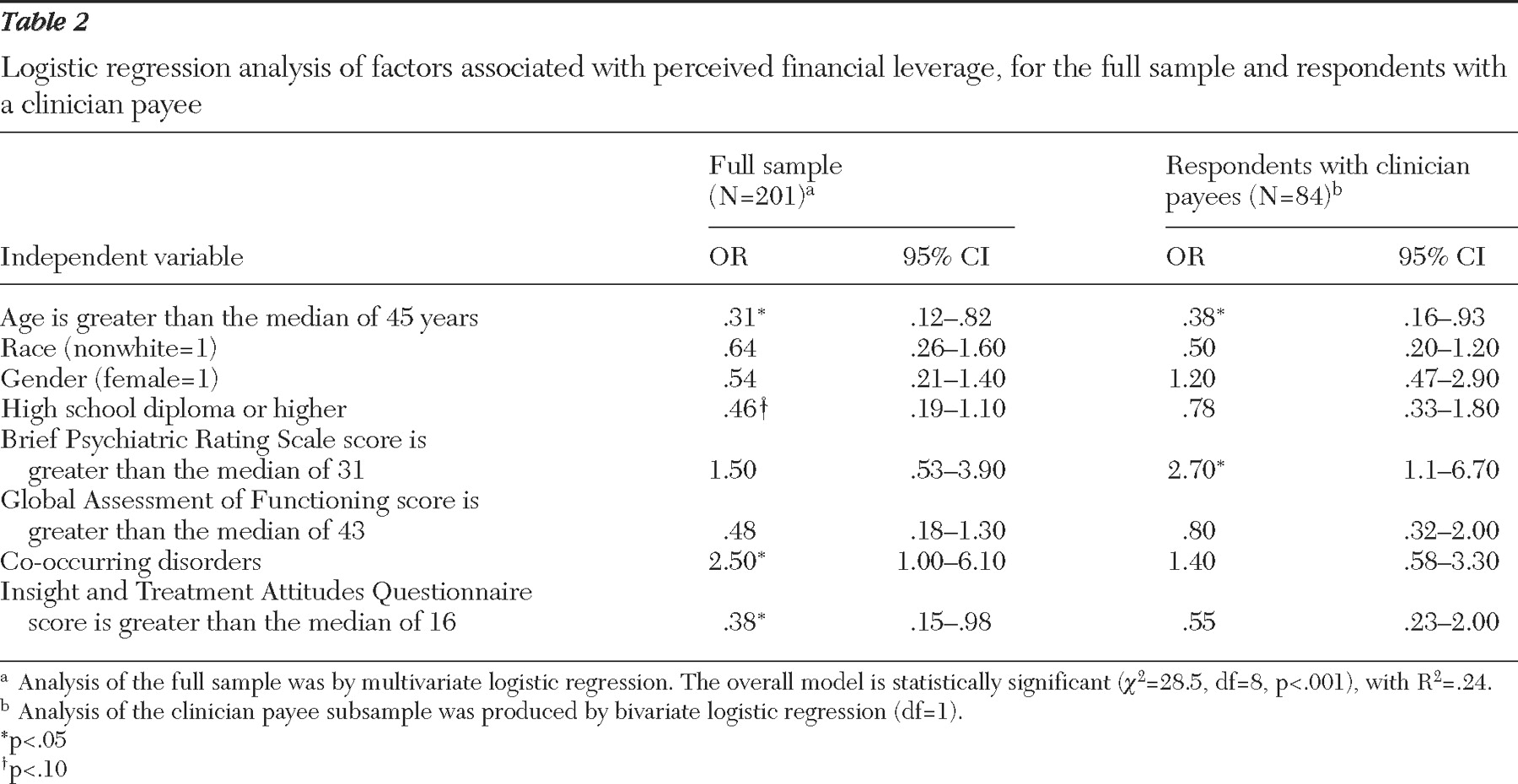

First, logistic regression analyses were conducted to identify extraneous variables that increase risk of financial leverage, because these factors might represent potential confounds of the effect of financial leverage on the client-provider relationship. Multivariate analyses of the entire sample of 201 respondents and bivariate analyses of the subsample of 84 respondents with clinician payees are shown in

Table 2 . In the full sample, those reporting financial leverage were significantly more likely to be younger than the median age, to have co-occurring psychotic and substance use disorders, and to indicate less insight into their illness (model

χ 2 =28.5, df=8, p<.001), consistent with analyses across sites reported elsewhere (

18 ). Within the subsample of respondents with clinician payees, younger age (younger than 45) and greater symptom severity significantly increased the odds of perceived mental health financial leverage. In other words, among individuals at higher risk of financial leverage (such as those whose money is managed by a mental health professional), being younger and having more severe symptoms represented additive risk factors.

Next, hierarchical multiple regression was used to assess whether having a clinician payee and experiencing financial leverage were associated with differences in the bond and conflict subscales, after analyses controlled for covariates that were identified as risk factors for financial leverage (age, education level, co-occurring disorders, functioning, insight level, and symptom severity). Neither mental health payeeship nor financial leverage was significantly associated with client ratings of the bond dimension of the working relationship (results not shown).

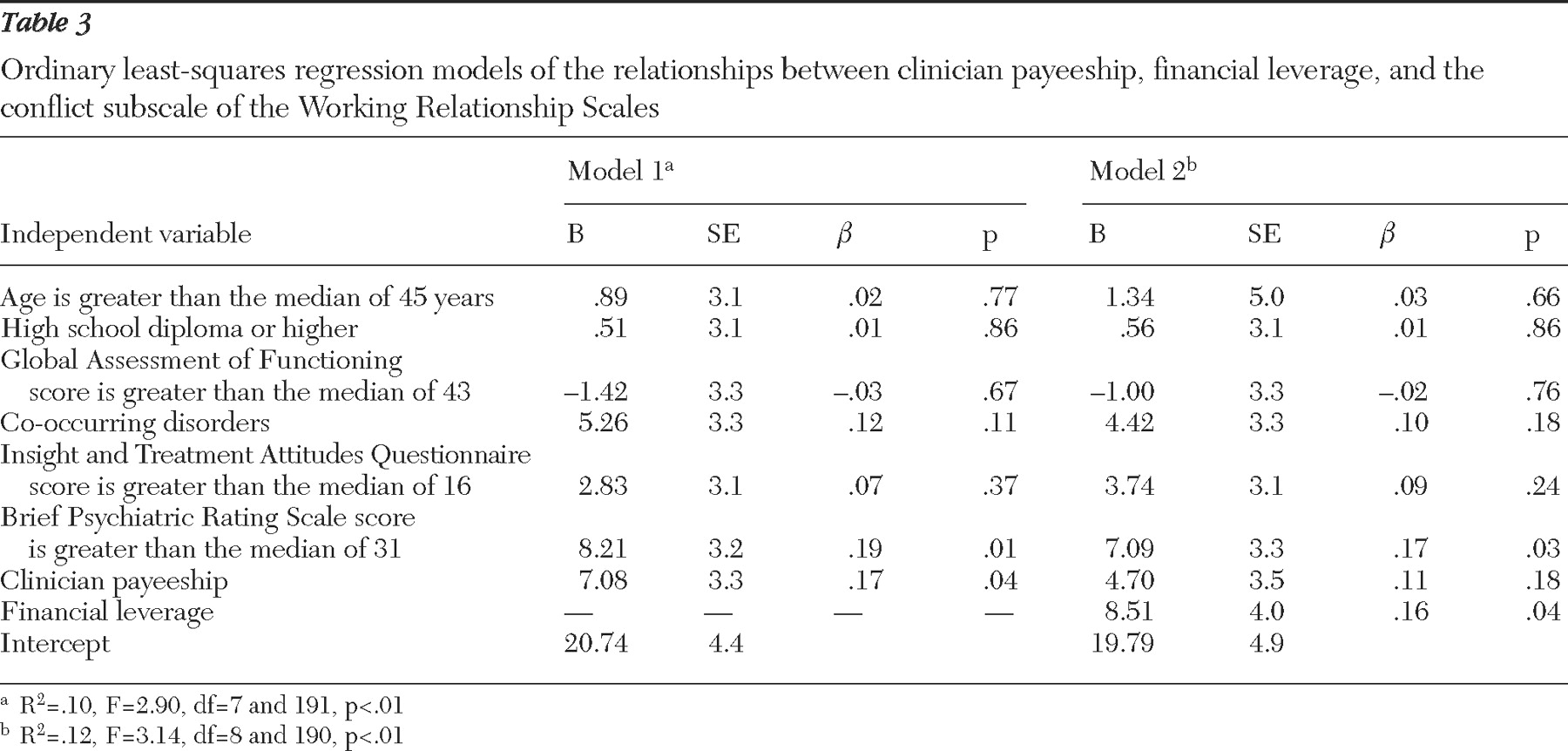

In the model predicting the conflict dimension (

Table 3 ), having a clinician payee, when entered alone, was associated with higher levels of conflict (model 1). When financial leverage was entered in the second step (model 2), however, a different pattern emerged: financial leverage was associated with higher conflict scores, and its addition suppressed the previously significant relationship between clinician payeeship and conflict. This pattern of findings suggests that the difference in conflict scores between individuals with and without clinician payees is explained or mediated by financial leverage, according to the criteria developed by Baron and Kenny (

35 ). That is, the relationship between the independent variable (clinician payeeship) and the outcome (conflict) was significantly attenuated when the mediator (financial leverage) was taken into account.

As more recent guidelines suggest (

36 ), we conducted a formal test of the significance of this mediating effect. Because the frequency of financial leverage was relatively small, the attenuation of power was a concern, particularly given the number of covariates in the model. To increase the efficiency of the test, we used bootstrap methods to estimate a confidence interval for the mediation effect (

37,

38 ). Controlling for clinical and demographic variables (age, education level, co-occurring disorders, functioning, insight level, and symptom severity), we estimated the following regression equations: path a, correlation of the initial variable (clinician payeeship) with the mediator (financial leverage); path b, correlation of the mediator (financial leverage) with the outcome variable (conflict), with controls for the initial variable; and path c, correlation of the initial variable (clinician payeeship) with outcome (conflict). If all three conditions were met, the final step, path c′, was to determine whether the effect of clinician payeeship on conflict was significantly reduced when the mediator (financial leverage) was controlled.

The significance of this mediated effect was tested by computing the product of paths a and b and estimating a 95% confidence interval (CI) with 5,000 bootstrap samples. The estimated mean±SE mediated effect was 2.37±1.33, CI=.16–5.52). Because zero does not lie within the confidence interval, the indirect effect of financial leverage was significantly different from zero at p<.05. Thus the test result suggests that financial leverage mediated the relationship between payeeship and therapeutic relationship conflict.

Discussion

Recent research provides a mixed picture of the effects of representative payeeship, in that studies suggest that it appears to improve functional outcomes but may produce unintended negative consequences, such as interpersonal conflict and even violence directed at payees (

5,

8,

9,

10,

11 ). This study explored the hypothesis raised in previous research that payeeship arrangements conducted within mental health treatment contribute to disruption of the client-provider relationship. The study also examined the mediating influence of financial leverage on this relationship.

Clinician payeeship was a common arrangement in this sample, particularly among individuals with substance use disorders and severe mental illness with significant functional impairment and low levels of insight about their illness. As noted in a recent report focusing on all five sites of this study (

18 ), our site appears to be unusual in the frequency with which these arrangements occur. Financial leverage was more frequently reported by younger and more severely symptomatic respondents, a pattern similar to previous findings that financial leverage and other limit-setting interventions are often used when consumers are seriously impaired or demonstrate adherence problems (

13,

15,

17,

39 ).

Respondents with clinician payees (relative to those with family or friend payees or no payees) reported more conflict in the case management relationship but had no difference in their bond scores in comparison with the other respondents. This finding suggests that clients with mental health provider payees develop similarly strong attachments to their case managers as those held by their counterparts in other types of money management arrangements; however, they experience more negativity and intrusion in the case management relationship. This finding is consistent with research discussed above that highlights the potential for conflict in clinician payee relationships (

6,

11 ), although this study is the first to document this effect from the perspectives of consumers in a mixed sample of clients with and without payees.

We also found, however, that the relationship between clinician payeeship and the therapeutic alliance was explained by its differential association with perceived financial leverage. Thus the analysis suggests that payeeship leads to strain in the therapeutic relationship when it is used as a mechanism for promoting adherence. Previous research has characterized representative payeeship as a treatment mandate because it represents an opportunity context for behavioral leverage (

40 ). In other words, the legal mechanism of payeeship is not intrinsically coercive but may be used strategically as a source of pressure to use or adhere to treatment. Our finding underscores this distinction. That is, although payeeship grants clinicians the capacity to regulate adherence through the contingent withholding of funds, it is the perception of actually being pressured to adhere in order to access those funds that is linked to disruption in the treatment alliance. In a similar vein, research on the process of psychiatric inpatient admission demonstrates that it is the extent of pressure applied to patients, particularly negative pressures—analogous to financial leverage in the community context—that most strongly determines the level of perceived coercion (

41,

42,

43 ).

The potential threat that financial leverage poses to the case management relationship should not be taken lightly, given that the alliance appears to play a pivotal role in the engagement, retention, and successful treatment of clients in mental health services (

44,

45 ). Furthermore, consumer surveys suggest that relationships with providers are among the most valued aspects of treatment, and many consumers view these relationships as central to the recovery process (

46,

47,

48,

49 ). As other recent work reports, consumers report fairly high levels of satisfaction with certain aspects of payeeship services, such as budgeting assistance, when they are offered within the clinical setting (

6,

50 ). Taken together, these findings suggest that a therapeutically optimal way to use payeeship may be to focus on building skills for eventual financial independence rather than using the mechanism as leverage to promote adherence. On the other hand, it is possible that using financial leverage in a collaborative contingency management contract would be perceived by consumers as less intrusive than financial leverage administered in an ad hoc manner (

2,

51,

52 ). Examining such contextual effects could be a fruitful avenue for future study.

This study has several methodological limitations. Because perceived financial leverage was measured from the client perspective, this inquiry cannot determine whether it actually happened. It is possible, for example, that consumers who perceive conflict with their case managers might overreport experiences of financial leverage, which would therefore overestimate the relationship between the two. As noted elsewhere (

53,

54 ), measuring treatment pressures via client self-report is a common limitation in much of the extant research on coercion, yet alternative methods are both impractical and costly. In the only existing study to triangulate perspectives on treatment pressures, Lidz and colleagues (

54 ) found that consumer self-report, though imperfect, correlated more highly with an observer-rated criterion measure than did the self-reports of professionals. In light of the limited alternatives available, relying on consumer reports of financial leverage is thus a reasonable strategy. Nonetheless, further study using clinician reports or independent observation of leverage is warranted.

Because money management characteristics were not manipulated experimentally, we cannot rule out the possibility that unobserved factors not controlled for in our models account for the relationship between perceived financial leverage and the client-rated conflict subscale. For example, we lacked information on whether payeeship was involuntary, which was predictive of a weaker alliance in a previous study of clients with representative payees (

12 ). Because the data reported here are cross-sectional, this study likewise cannot establish the direction of the observed relationships. Finally, we note that the setting studied is unusual in that the clinic offered a large-scale money management program; however, there is wide variation in the availability and use of such institutional payeeship arrangements (

18 ). Thus the findings may be less applicable to settings in which payeeship functions are performed primarily by family members, attorneys, or social service providers.