Depression burdens nearly one in six persons over age 65 with substantial morbidity, mortality, and costs (

1,

2,

3 ). Although treatment consists almost entirely of antidepressants (

4,

5 ), pharmacotherapy for depression among older populations can be problematic (

6,

7 ). Perhaps partly a result of high costs, many elderly persons with depression never begin appropriate antidepressant regimens, and of those who do, less than half fill prescriptions for 30 days or more (

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13 ).

Although the Medicare Modernization Act (MMA) in the United States improves seniors' access to antidepressants through Medicare Part D coverage, it may also lead to large expenditures for these medications (

14 ). There are particular pressures to control such psychotropic costs, because the proportion of spending on prescription drugs is twice as high in mental health care as in general health care (

15 ). Costs of psychotropic medications have increased 17% annually, far outpacing other mental health expenditures and spending increases on medications overall (

15,

16 ). Newer agents with potentially greater tolerability are widely available (

16,

17,

18 ), making antidepressants among the most widely prescribed classes of medications in most health care systems (

19,

20 ).

Prescription benefit plans operating under Medicare Part D use many strategies to contain costs, including via copayments, coinsurance, income-based deductibles, and combinations of these (

21 ). Copayments require a fixed amount to be paid for each prescription. Copayments also can be tiered, with the lowest tier for generics, requiring small copays, and higher tiers for brand names, requiring larger copays. Coinsurance requires payment of a proportion of the medication price. Coinsurance policies have been criticized as being unfair to sicker patients who require more medications (

22 ). Therefore, most coinsurance policies have annual out-of-pocket ceilings; costs up to the ceiling are paid out of pocket, whereas costs above the ceiling are reimbursed. Ceiling amount also can be linked to income in the prior year, under the presumption that patients with higher incomes can afford to pay more for medications. Such forms of cost sharing might reduce payers' expenditures by increasing patients' out-of-pocket contributions, thereby ensuring the fiscal viability of medication assistance programs for seniors. However, some analysts argue that coverage restrictions will adversely affect the elderly population's use of essential medications (

23,

24 ). For these reasons, it is critical to understand how medication cost sharing affects older patients, especially those who use antidepressants.

Aims of this study were to evaluate the impact of two sequential large-scale "natural experiments" in cost sharing on antidepressant use among seniors in British Columbia, Canada. In January 2002 the province-funded prescription benefit program introduced a copayment ("copay") policy requiring a $25 Canadian copay ($10 Canadian for low-income seniors). In May 2003 this copay policy was replaced by a second policy, which featured an income-based deductible, 25% coinsurance once a beneficiary's deductible was met, and full coverage once an out-of-pocket ceiling was met. The transition from one new policy to the next emulates the experience of many U.S. seniors who transitioned from private insurance programs requiring copays to Medicare's medication coverage system requiring deductibles and coinsurance. This natural experiment among all elderly British Columbia residents provided a unique opportunity to evaluate the impact of these two sequential cost-sharing interventions on antidepressant utilization, initiation, and discontinuation.

Methods

Data

Prescription records were obtained from the PharmaNet database, which contains records of all prescriptions dispensed at community pharmacies in British Columbia, regardless of payer, since 1996. Underreporting and misclassification are minimal (

25 ). Prescription records were linked by encrypted personal health numbers to Ministry of Health administrative databases for physician services, hospitalizations, and deaths. These databases contain diagnostic codes and dates of service, admission, or death. The completeness and misclassification of diagnostic coding are probably similar to comparable databases (

26,

27 ).

Antidepressant utilization

Our primary analysis included all British Columbia residents age 65 and older and focused on patterns of antidepressant dispensing from January 1, 1997, to December 31, 2005. Because the cost-sharing policies could have affected the number of prescriptions filled and the strength of those prescriptions, we sought a dispensing metric that would be sensitive to both types of changes. For each medication, we converted the number of milligrams dispensed into the number of milligrams of imipramine that would be equivalent in strength (

28 ) and tallied the number of imipramine-equivalent milligrams dispensed each month. Monthly dispensing was then divided by the British Columbia senior population during that month (

29 ). Because bupropion is marketed for depression and smoking cessation and the indication cannot be determined with certainty from claims data, we excluded bupropion in our primary analysis but included it in a sensitivity analysis.

Antidepressant starting and stopping

To better understand dispensing patterns, we computed monthly rates of antidepressant starting and stopping. Starting an antidepressant was defined as filling a prescription and having no antidepressant fills in the previous six months. Numbers of new starts were tallied over the British Columbia senior population. In a second analysis, we restricted the study population to persons with a recorded depression diagnosis and no antidepressant use in the past six months. Persons counted toward the denominator of this cohort until they filled a prescription for an antidepressant or until six months had elapsed since their most recent depression diagnosis.

For our stopping analysis, we first identified persons as they initiated antidepressant therapy, defined as filling an antidepressant prescription without having filled one in the past year. Individuals were allowed to contribute multiple episodes of use to this analysis. We then created a patient coverage diary for each treatment period by stringing together consecutive prescriptions based on pharmacist-reported days' supply dispensed, calculated days' supply available from previous fills, and fill dates. Stopping was defined as failing to refill a prescription within 90 days of exhausting available supply, and the patient was assumed to have stopped on the date when his or her supply should have run out. Individuals were considered part of the cohort until death, emigration, discontinuation, or one year elapsed after initiation, whichever came first. We calculated monthly stopping rates as the number of persons stopping an antidepressant during the month divided by the number of persons in the cohort during that month.

Statistical analyses

Trends in antidepressant utilization, initiation, and discontinuation were plotted over time. Segmented linear regression was used to identify changes in slope or level at the time of the policy changes (

30 ). Our multivariate linear regression models of aggregated monthly rates included a constant term, a linear time trend, a binary indicator for the period after the introduction of the copay policy, a linear trend for time since the copay policy, a binary indicator for the period after the introduction of the income-based deductible policy, and a linear trend for time since the income-based deductible policy. For selected models we additionally included indicator terms for December and January to model year-end stockpiling. In our main model, effects of the income-based deductible policy were estimated relative to trends during the copayment policy period. In a secondary analysis, we compared trends during the income-based deductible policy directly with trends during the baseline policy. The parameter estimates of this model estimated the cumulative effect of the two policies. A Durbin-Watson test was used to determine autocorrelation, and where appropriate, an autoregressive error process was specified. Statistical significance of policy effects was determined from two-sided t tests.

This study was approved by the institutional review boards at Brigham and Women's Hospital as well as the University of Victoria in British Columbia.

Results

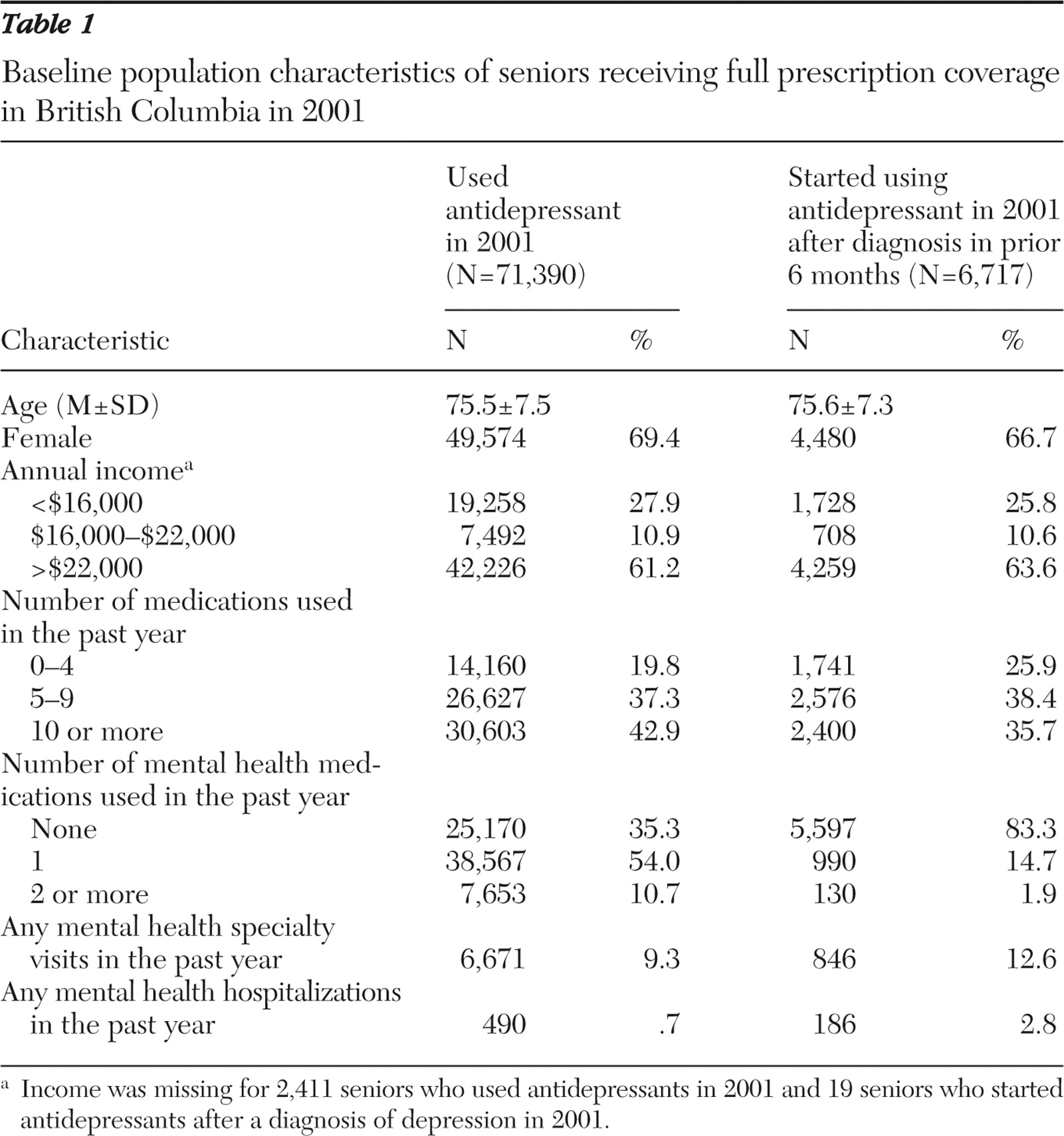

Table 1 shows baseline covariates for our population during 2001, which represented the full-coverage period immediately before the policy change and occurred midstudy. The average age of current antidepressant users was 76; 69% were women. A total of 64% of patients had received at least one mental health prescription in the prior year, 9% had had at least one mental health specialty visit, and less than 1% had been hospitalized for mental health reasons. The subset of patients who were new users of antidepressants during this period and had a depression diagnosis in the previous six months was similar to the full group but used fewer mental health medications and fewer medications overall.

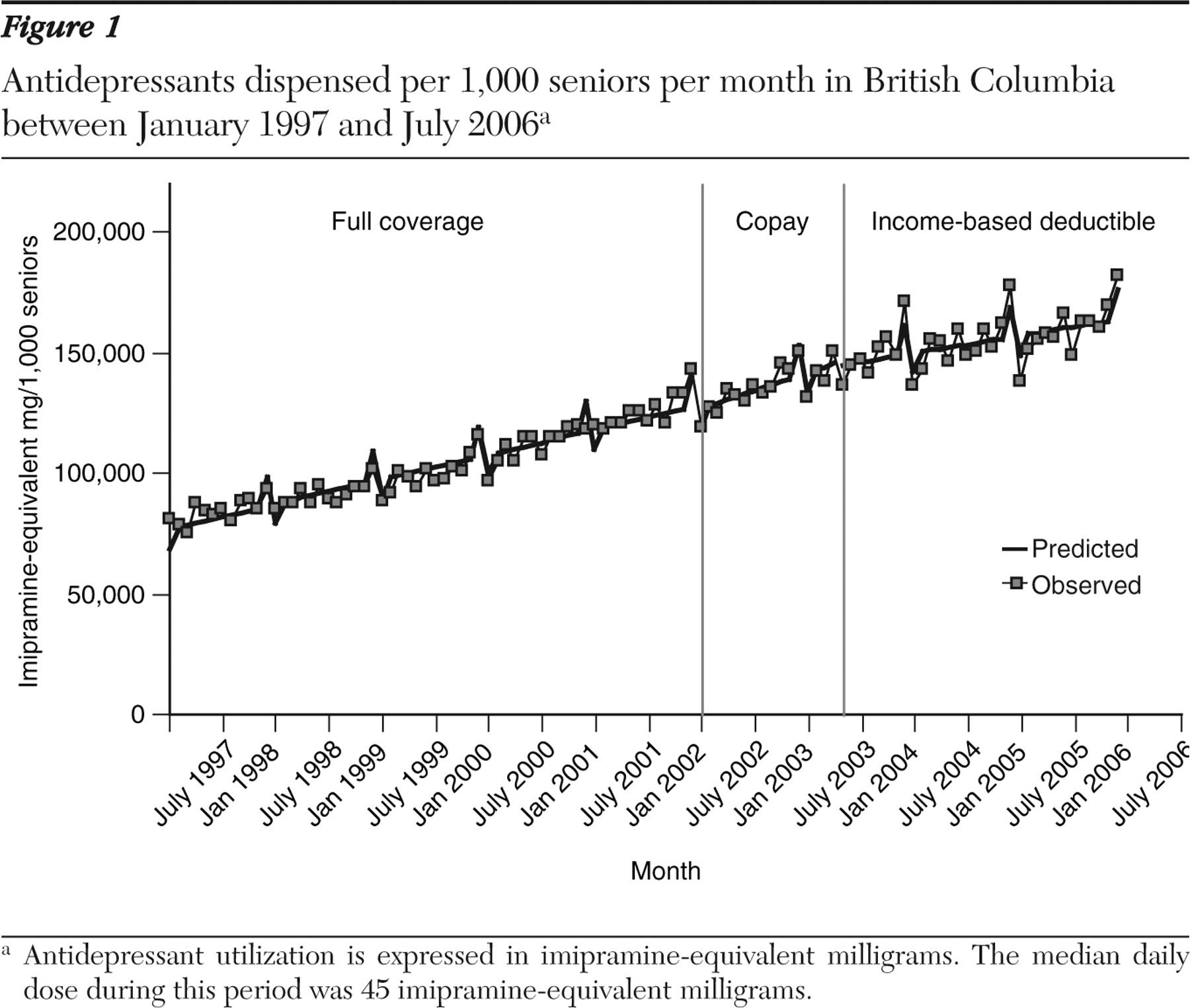

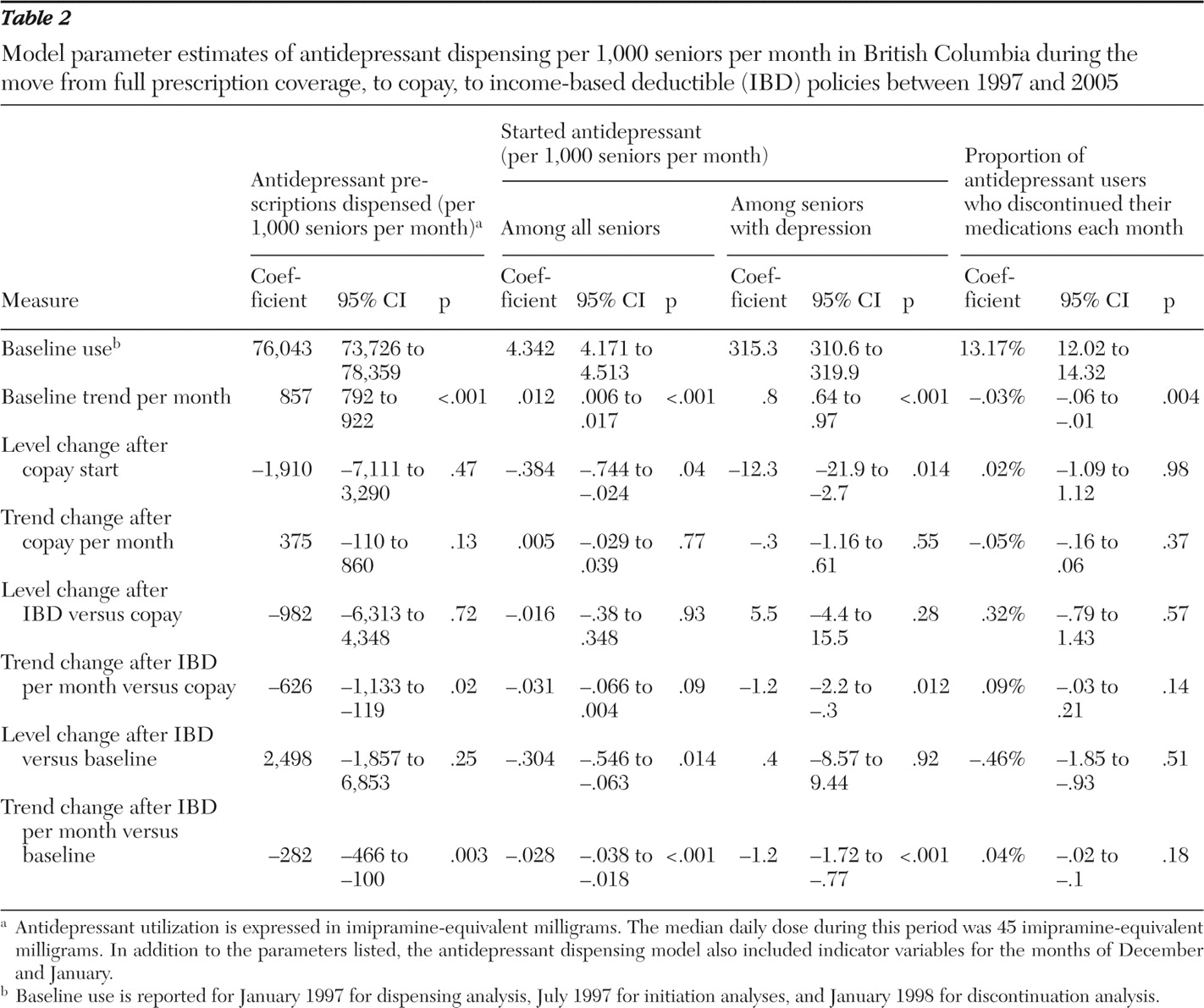

From 1997 to 2001, antidepressant dispensing increased at a rate of 857 imipramine-equivalent milligrams per month per 1,000 seniors (95% confidence interval [CI]=792 to 922) (

Figure 1 ). Observed and predicted values are shown in

Figure 2, and model parameter estimates are reported in

Table 2 . The median daily dose of 45 mg of imipramine per day during this period equates to an additional 19 patient days' worth of antidepressant dispensed.

The implementation of the copayment policy in January 2002 was associated with a drop in dispensing by 1,910 mg per month (CI=-7,111 to 3,290; 42 patient-day decrease in days' supply per month), but the growth rate of dispensing increased by 375 mg per month after the policy change (CI=-109.7 to 860.2; change in slope=decrease of eight patient-days per month). The subsequent implementation of the income-based deductible policy resulted in a nonsignificant decrease in the dispensing level and a significant decrease in the rate of dispensing growth by 626 mg per 1,000 seniors per month (CI=-1,132.8 to -119.3; change in slope=decrease of 14 patient-days per month). When the income-based deductible period was compared directly with the baseline period, there was no change in dispensing level, but dispensing growth slowed by 283 imipramine-equivalent milligrams per month (CI=-466.3 to -99.6).

The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) increased substantially over the study period. SSRIs accounted for 42% of imipramine-equivalent milligrams dispensed in January 1997, with this proportion increasing to 63% by December 2005. Use of new and second-generation agents as a proportion of total use also increased, from 11% to 22%, whereas tertiary amine use as a proportion of total use fell from 37% to 15%. Within the SSRI class, citalopram market share increased rapidly from the medication's first use in April 1999 to December 2005, when it accounted for 50% of total SSRI use. [A list of antidepressants included in the evaluation is provided as an online supplement to this article at ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

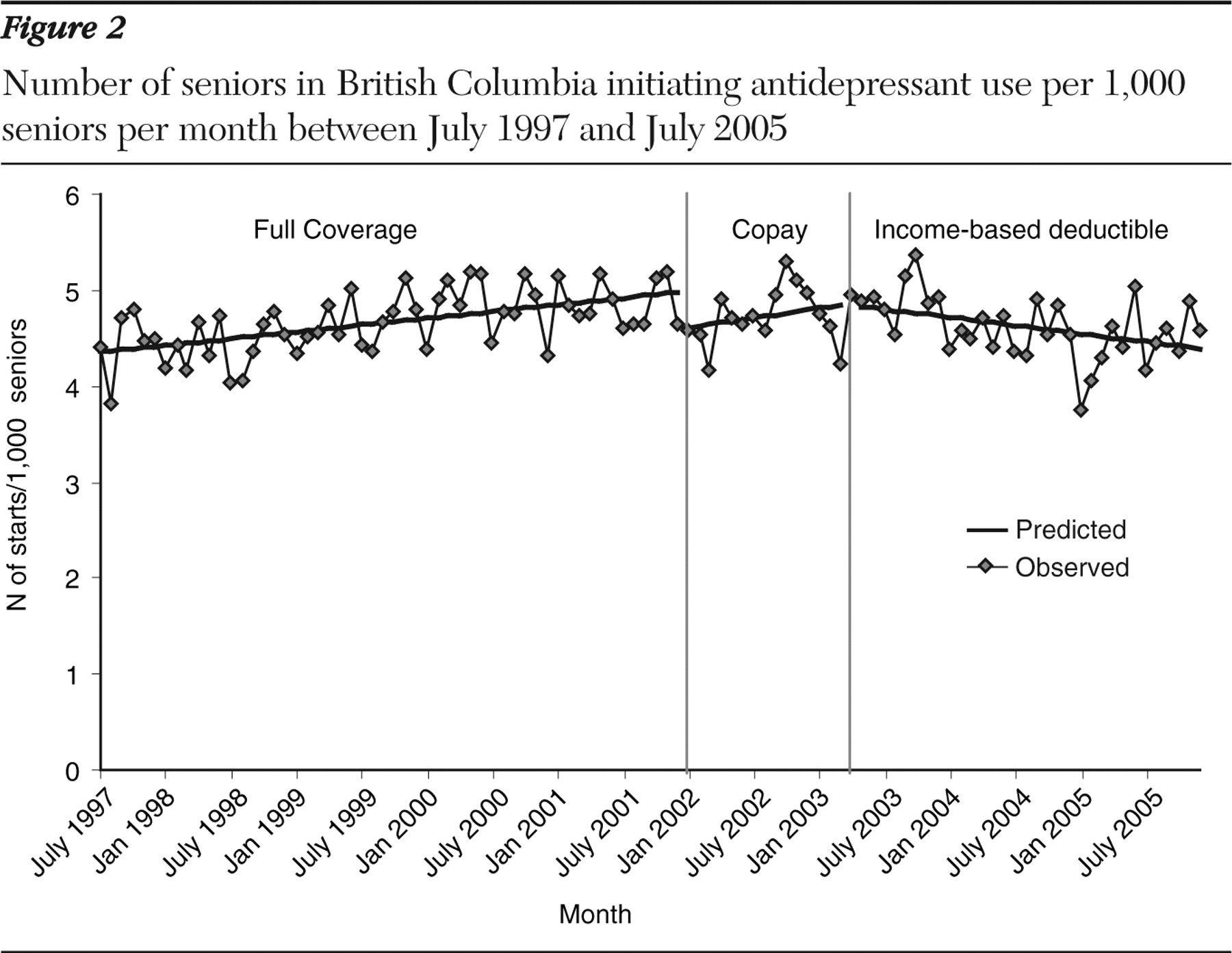

Rates of antidepressant initiation are shown in

Figure 2 . Antidepressant initiation increased from 4.3 starts per 1,000 per month in January 1997 to 5.0 starts per 1,000 per month in December 2001. The implementation of the copay policy was associated with a significant .38 per 1,000 drop in initiation level but no change in the rate of increase over time (

Table 2 ). Growth in initiation rates slowed minimally by .03 starts per month (CI=-.066 to .004) with the introduction of the income-based deductible and coinsurance policy. Relative to the baseline period, the initiation level was reduced by .3 starts per 1,000 seniors (CI=-.55 to -.06), and the growth in initiation rates slowed by -.028 per 1,000 seniors (CI=-.038 to -.018).

Among patients with a recorded depression diagnosis in the prior six months and no use of antidepressants during that period, the baseline frequency of antidepressant initiation was 315 starts per 1,000 seniors in January 1998, which increased by .8 starts per 1,000 seniors per month over time (CI=.64 to .97) (

Table 2 ). [A figure showing the number initiating antidepressants per 1,000 seniors per month with a recorded depression diagnosis in the previous six months is provided in an online supplement to this article at ps.psychiatryonline.org.] The copay policy resulted in a significant drop of 12.3 starts per 1,000 seniors (CI=-21.9 to -2.7). The income-based deductible policy resulted in a significant trend toward decrease (-1.2 starts per 1,000 seniors per month, CI=-2.2 to -.3). A similar decreasing trend and no change in number of starts per 1,000 seniors with depression were observed when comparing the coinsurance period directly with the baseline period.

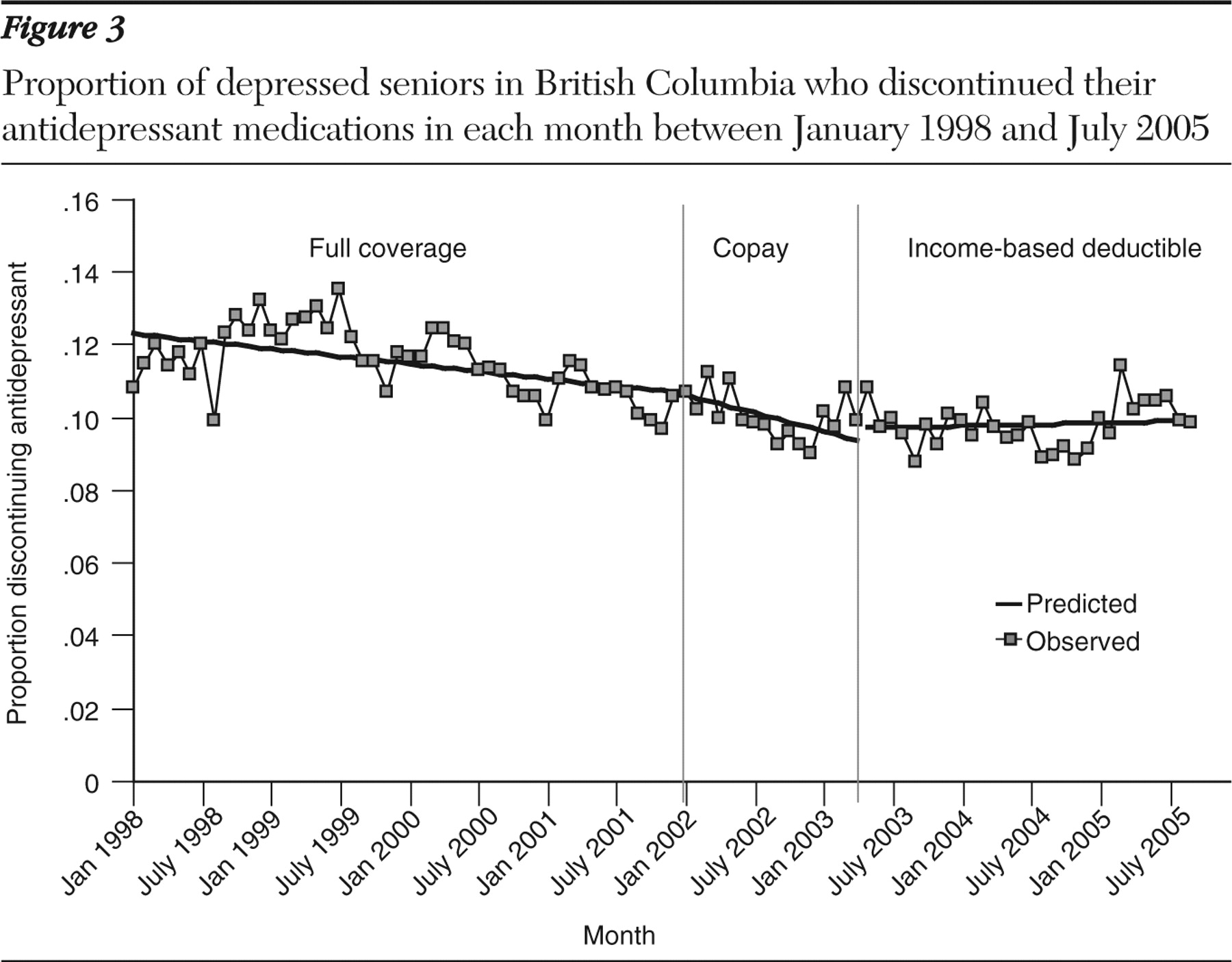

At baseline 13% of antidepressant users stopped their medication each month. Rates of stopping decreased by .03% per month over time (-.06% to -.01%) (

Figure 3 and

Table 2 ). The implementation of the copayment and income-based deductible policies did not have a significant effect on stopping rates at the population level.

Discussion

In this study of the general population of seniors in British Columbia, we found that implementing a copay policy led to an observable drop in antidepressant initiation. Replacement with an income-based deductible plus coinsurance policy also was associated with a slowing of the rate at which antidepressant use had been increasing. Neither policy affected the rates of antidepressant discontinuation.

Prior studies of the impact of cost-sharing mechanisms on medication utilization are generally consistent with these findings. Most (

22,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38 ) but not all (

39 ) studies of copayments have observed declines in drug prescriptions ranging from 5% to 10%, even with relatively modest copays. Doubling copayments has reduced antidepressant use by 25% (

40 ). The RAND health insurance experiment found that medication use was reduced by 33% in plans with 95% cost sharing (roughly equivalent to the uncovered period before patients reach their deductible in our study) (

37,

38 ). Introduction of a 25% coinsurance and income-based deductible policy among seniors in Ontario was associated with a 9% reduction in use of essential medications (

22 ).

Several potential mechanisms could explain how increased sharing of medication cost decreased antidepressant utilization and initiation. A majority of seniors spend $500 or more per month for their medications (

41 ), and they may be particularly sensitive to high costs because of their diminished financial resources (

42 ). Even elderly persons with prescription benefits may be unable to cover increased cost sharing because of their generally fixed incomes (

37 ). High costs may particularly curtail antidepressant use because of the stigma associated with mental health treatments among seniors (

10,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47 ). Older patients also frequently take multiple regimens for comorbid conditions and may decide to limit their antidepressant use so that they can pay for their other medications (

22 ).

These results should be interpreted with several potential limitations in mind. Because of the sequential implementation of the policy changes in British Columbia, it is difficult to estimate the effect of a direct change from full coverage to an income-based deductible policy. Although we have compared trends during the application of the income-based deductible policy with those during the application of the baseline policy, medication use patterns after the income-based deductible period may have been affected by the introduction of the copay policy. The other comparison we have reported—that of the effect of the income-based deductible policy compared with the copay policy—may underestimate the impact of a shift from full coverage to the income-based deductible system because some patients who would have experienced "sticker shock" after the income-based deductible policy went into effect may already have done so after the transition from the full-coverage policy to the copay policy. Furthermore, the impact of the income-based deductible policy may have been mitigated because 60% of patients had already met their deductibles when the policy was introduced in May 2003. Notably, we observed evidence in December 2003 of seniors stockpiling antidepressants, an indication of their concern about facing the full deductible in subsequent months. It may be that by 2004, when seniors faced the full deductible, they had nearly two-thirds of a year to cope with and adapt to the full income-based deductible policy.

Another limitation is the lack of a concurrent control group. Because the policy changes affected all seniors in British Columbia, with the exception of noncomparable populations (for example, seniors residing in nursing homes), no appropriate concurrent control group exists. The validity of an uncontrolled time trend analysis rests on the assumption that no sudden changes resulting from other interventions or changes in the population occurred at the same time as the interventions of interest. However, the suddenness of the changes observed in our analysis and their coincidence with the policy changes suggest that they are attributable to the policy changes.

Finally, cost sharing did not appear to affect some utilization outcomes (for example, discontinuation), and it remains unclear to what extent any reductions in antidepressant use that did occur resulted in clinically meaningful consequences. However, age-related pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes could make seniors particularly vulnerable to regimens used inappropriately to save costs, increasing their risks of morbidity, hospitalizations, emergency room visits, nursing home placements, or even death from causes such as suicide (

7,

48 ). In part because of these possibilities, the net economic savings to insurers from these cost-sharing plans might also be less than anticipated (

49 ). Prior studies of cost-sharing policies have been mixed, with some (

50,

51 ) but not all (

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59 ) finding increases in health care utilization outcomes and diminished savings after implementation. One study of limiting reimbursement for specifically psychotropic medications found that it led to increases in other health care expenditures that exceeded savings on psychotropic medications by a factor of 17 (

60 ). Without measures of the severity of depression or other indications for antidepressants, it is unclear whether any decreases in use observed here represent an increase in unmet needs. However, given the substantial underutilization of depression treatments by older adults (

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13 ), there are grounds to suspect that decreased use may have caused unmet need.

Conclusions

With the assumption that undertreatment of depression among elderly patients remains a significant public health problem, efforts to increase their utilization of treatments continue to be needed (

8,

9,

10,

12 ). Model programs have been developed and have already proven successful at overcoming barriers to care and improving clinical outcomes among elderly persons with depression (

61 ). Our results suggest that successful implementation of such model programs may also require taking into account and potentially intervening on any reductions in antidepressant use caused by patient cost sharing. Second, it remains crucial to continue conducting comparative research on different cost-sharing mechanisms and examining their effects on utilization, health, and economic outcomes. In this way, evidence-based and fiscally sound prescription drug policies can be designed for extremely vulnerable older populations with mental disorders.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by grant R01-MH-069772 from the National Institute of Mental Health, grant R01-AG-021950 from the National Institute on Aging, and grant 5-R01-HS-010881-07 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Dr. Schneeweiss has received research grants from Pfizer, Inc. The other authors report no competing interests.