As the primary locus of mental health care has shifted from the hospital to the community, high prevalence rates of mental illness have been found in incarcerated populations. Best estimates indicate that between 10% and 16% of people incarcerated in state prisons can be considered to have a mental illness (

1,

2,

3 ). Explanations for this high prevalence usually focus on increased numbers of persons with mental illness cycling through the criminal justice system (

1,

4 ). However, limited research suggests that inmates with mental illness have greater difficulty getting released on parole (

3,

5,

6 ), serve longer prison sentences (

2 ), and serve greater proportions of one's sentence in prison (

5 ). These findings suggest that persons with mental illness may serve more time in prison and are more likely to serve a full sentence before being released, as opposed to receiving parole.

Using data from the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, this study took a closer look at the relationships between the receipt of mental health services in prison and both the likelihood of serving a full sentence and the amount of time served in prison.

Methods

The data used in this study come from Pennsylvania Department of Corrections' administrative records for men who were released from the Pennsylvania state prison system between 1999 and 2002 to locations in Philadelphia County. Records used for this study include incidences where the prison episode commenced upon conviction (as opposed to a return to prison after revocation of parole) and incidences where the men were either paroled or served their full sentence. A total of 7,046 records were included in this data set.

The primary measures of interest were the outcome measures—type of prison release (served full sentence or paroled) and length of prison episode—and the covariate that categorized the mental health services received while incarcerated, taken at the time when the most recent classification was made. The latter measure reflects that these services were administered at one of three levels of intensity. Persons receiving the most intensive level of services were denoted as being on the "psychiatric review team"; the second level represents persons who received ongoing, albeit less intensive, services; and the third level includes persons who were not receiving any services at the time of release but had a history of receiving mental health services during the examined incarceration. Further information on diagnosis or specific services received was unavailable, but the two higher levels of services received are very likely to involve a diagnosis of ongoing mental illness, with the level of services corresponding to the severity of the illness and the willingness of the person to receive services. For the least intensive category, having a history of mental health services during the examined incarceration indicates a limited period of care and leaves more uncertainty about the extent of any accompanying mental illness.

Other measures available in the data set described criminal history: primary charge related to the incarceration (that is, the instant offense), history of prior offenses, the original date of incarceration for the instant offense (that is, reception date), release date, and disposition upon release (parole or served full sentence). The data also include an assessment of substance dependence by using the Texas Christian University Drug Screen II (

7 ), as well as measures of age, race or ethnicity, and year of release.

This brief report presents descriptive statistics. It also presents the results of logistic regression, which are presented as adjusted odds ratios to assess the association between receiving mental health services and the probability of serving a full sentence before release. Finally, I show the ordinary-least-squares regression results, an analysis performed to estimate the association between receiving mental health services and the duration of the incarceration episode from which the person was released. All measures described here were included in the regression models, but only the results related to the level of mental health services received are reported. Data management, matching, and analyses were performed by using SAS statistical software, version 9.1.

This study is a component of a larger project that examined service use by people who received mental health services while they were incarcerated; the project examined service use during incarceration and after prison release. The study was approved by the research review committee of the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections and the institutional review boards of the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia, the University of Pennsylvania, and the City of Philadelphia.

Results

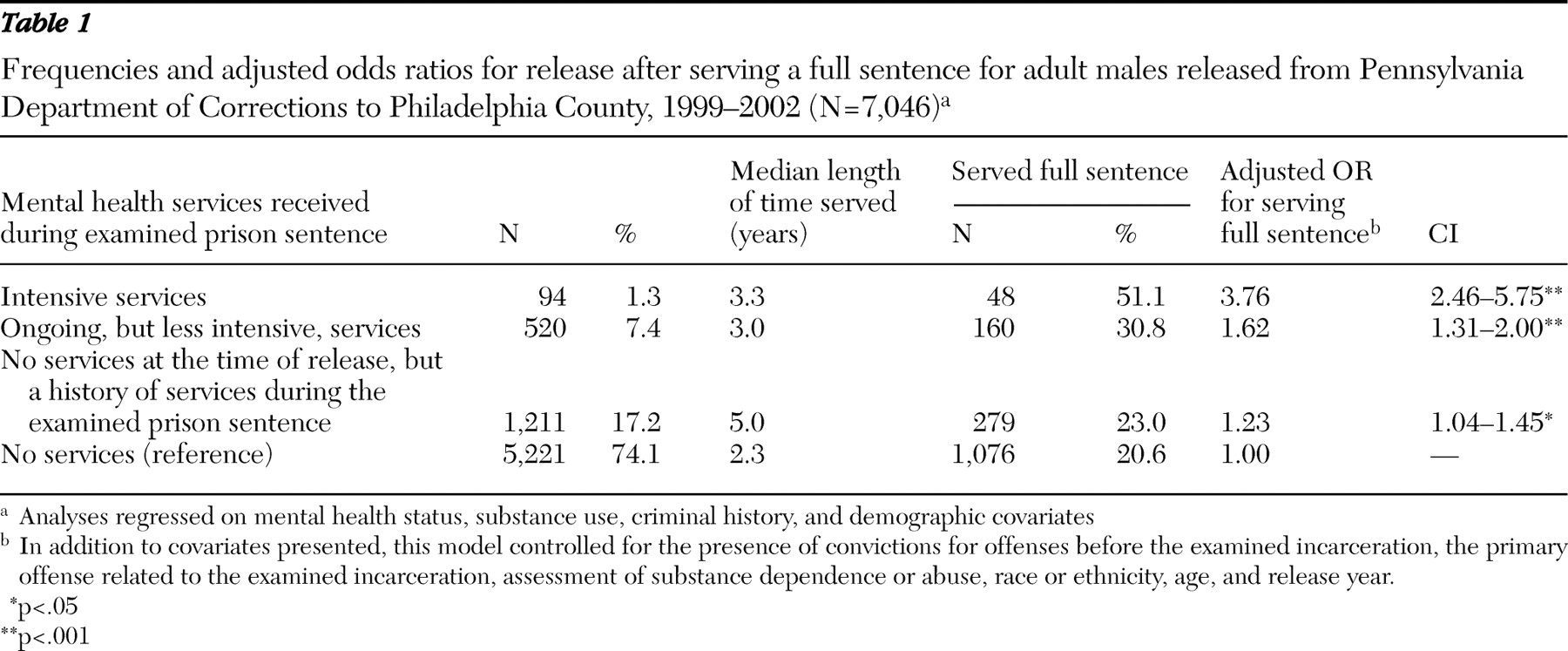

As shown in

Table 1, of the 7,046 men in the sample, 8.7% received ongoing or intensive mental health services, and as many as 25.9% of the persons in the sample received some type of mental health service while incarcerated. Almost one-third (30.8%) of those who received ongoing services and over half (51.1%) of those who received intensive services served their full prison sentences, compared with less than one-quarter of those in the other two subgroups. By length of time served, the median episode lengths ranged from 5.0 years for the subgroup with a history of services to 2.3 years for those without treatment. The ongoing and intensive services subgroups had median stays of 3.0 and 3.3 years, respectively.

Table 1 also presents adjusted odds ratios (AORs) that were calculated from fitting a logistic regression model. AORs showed that receipt of intensive services was associated with 3.76 times greater odds of serving the full sentence, compared with receipt of no services. The comparable AORs for the subgroups receiving ongoing services and having a history of services were both more modest, at 1.62 and 1.23, respectively. These AORs all take into account significant associations found in the model between the dependent variable (type of exit) and various covariates: record of previous offenses, type of offense committed, assessment of substance dependence, race or ethnicity, and age.

Results for the ordinary-least-squares regression model assessing associations between level of mental health services provided (along with control variables) and length of time spent in prison are not presented. The association between prison episode length and receipt of services varied depending on how episode length is adjusted—for example, unadjusted, logged, truncated, and nonparametric rank order. History of receiving services was the only service level to show a robust and substantial positive association with episode length. The level of significance associated with the ongoing services category was sensitive to how the dependent variable was measured, and the intensive services category consistently showed a nonsignificant association.

Discussion and conclusions

This study found that 8.7% of 7,046 men released from Pennsylvania State prisons to Philadelphia locations between 1999 and 2002 were receiving ongoing or intensive mental health services at the last point before release when the data were collected, and as many as 25.9% of this release cohort were receiving some mental health services while incarcerated. All three identified subgroups of persons receiving mental health services had significantly increased odds of serving their full sentence. However, the associations between these subgroups and the length of time served before release from prison were not as conclusive.

Limiting parole for persons receiving mental health services while in prison limits the ability to tailor their release conditions. Parole can potentially act both as a means of supervision and as a gateway for access to community mental health and other services that facilitate successful reentry from prison into the community and reduce reincarceration. However, the lack of such community resources often impedes developing an acceptable parole discharge plan (

3 ). Specialized parole programs and programs that collaborate with parole supervision in providing intensive case management, assertive community treatment, housing, and other mental health services would also make parole a more viable option for persons diagnosed as having mental illness (

8 ). In the absence of funding for such programs through traditional mental health streams, more of these programs are being established by the criminal justice system (

9 ). The prospect of increasing options for parole for persons diagnosed as having mental illness provides an incentive for criminal justice entities to further pursue such initiatives. However, such involvement should not supplant the need for the mental health system to also provide more service options for this population (

10 ). In the meantime, these results suggest that persons who receive the most intensive mental health services while in prison are most likely to leave prison without support or supervision from the criminal justice system.

Although it was expected that the odds of serving the full prison sentence would increase as the level of mental health services got more intensive, the findings on length of incarceration episode were more counterintuitive, especially when considering that higher odds of serving the full sentence were at best only loosely coupled with longer time served in the prison episode. This suggests the existence of factors, only partially captured in this study, that may mitigate a straightforward relationship between mental illness and prison exit dynamics.

Findings also underscore one of the limitations of the study—that is, although receipt of mental health services presumably correlates with severity of mental illness, the reliability of such a de facto proxy for diagnosis is uncertain. Other factors, such as behavioral infractions or stressors related to incarceration, could lead to receipt of mental health services, especially services received in a limited fashion or over a limited time period, and these factors could also play a part in extending the length of a prison episode. Furthermore, additional time served could increase the opportunity for receiving mental health services. This may explain the association between length of time served and history of receiving mental health services and the absence of similar associations with more intensive mental health services.

This limitation is also present in Ditton's study (

2 ) of mental illness in incarcerated populations, one of the most widely cited studies on this topic. The study based mental illness on prisoner self-report of either a "mental or emotional condition" or an overnight stay in a psychiatric hospital. Differences in methodologies may explain the difference between the 25.9% rate for receiving mental health services found in the study presented here and the 16.2% prevalence rate found for mental illness in state prisons by Ditton's study, which was based on prisoner self-report of either a mental or emotional problem. More notably, the findings from the study presented here conflict with Ditton's findings that persons who are incarcerated and report mental illness serve considerably longer sentences than other offenders. As shown by the results of the study presented here, using a relatively undifferentiated measure of mental illness may conceal dynamics that confound the association between mental illness and longer prison sentences.

Despite limitations of the study presented here, the results suggest that the dynamics by which people exit the prison system play a potentially prominent role in the intersection between mental illness and incarceration, and greater attention needs to be paid to how and when people exit prison, both as a means for reducing the high rates of mental illness found among persons who are incarcerated and for providing a framework for facilitating successful reentry into the community.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Funding was provided by the Council of State Governments and the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections.

The author reports no competing interests.