Individuals with serious mental illness require both mental and medical health care services (

1 ). Difficulty in accessing outpatient services may produce overreliance on emergency services (

2 ), resulting in suboptimal care and adverse outcomes, including increased mortality, morbidity, and functional impairment. Identifying factors that interfere with the utilization of medical and mental health care services among consumers with serious mental illness could lead to strategies to improve such services.

Previous work suggests that mental health care consumers, especially those with more serious or disabling psychiatric conditions, perceive significant barriers to clinical care (

3,

4 ). Consumers experience various person-level, interpersonal, and system-level barriers to care. At the person level, demographic characteristics may be associated with difficulties with, delays in, or lack of receipt of clinical care among those with serious mental illness. These characteristics include age (

3,

4 ), race (

1 ), and financial resources (

3 ); clinical characteristics, such as greater functional disability (

3 ) and co-occurring mental illness and medical conditions (

4 ); and situational factors, such as personal crises (

5 ) and life stressors (

6 ). Factors related to interpersonal interactions, such as stigma (

7 ), distrust, and negative experiences with service providers or systems (

6,

8 ), may prevent service utilization. Finally, system-level factors, such as accessibility and availability of services (

9 ), also have been identified as barriers to accessing mental health care and medical care.

Few studies have focused on consumers with serious mental illness. Furthermore, with the exception of financial barriers, few studies have compared barriers to mental health care and medical services. Thus it is unclear whether consumers perceive similar barriers to mental health care and medical care. In this study we examined perceived person-level, interpersonal, and system-level barriers to medical and mental health care among consumers with serious mental illness; assessed the relationship between demographic characteristics, clinical factors, and perceived barriers; and determined the extent to which perceived barriers are similar or unique to different types of clinical care.

Methods

Data were drawn from a larger study designed to test the effectiveness of a brief three-month, critical time intervention for veterans with serious mental illness. Participants were recruited from four inpatient psychiatric units within the Veterans Affairs (VA) Capital Health Care Integrated Service Network (VISN 5). Participants were 18 to 70 years of age, lived within 50 miles of the inpatient facility, and had a chart diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum disorder (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or psychosis not otherwise specified) or mood disorder (major depression or bipolar disorder). All participants were at risk of treatment dropout; risk factors were defined as diagnosis of a co-occurring substance use disorder in the past year, medication nonadherence for the past year per the patient or the patient's medical chart, or an inpatient admission in the past two years, followed by a readmission, emergency visit, or no outpatient visits within 30 days postdischarge.

Consumers who consented to participate completed a 90-minute interview, which included assessments of demographic and clinical characteristics and barriers to clinical care. Items modified from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey were used to assess respondents' perceived barriers leading to difficulty with, delay in, or lack of receipt of mental health care (21 items) and medical care (22 items) in the six months before hospitalization. In the absence of predefined categories of barriers, a priori consensus among investigators yielded six distinct categories: money and finances, transportation and distance, time constraints, provider and institutional constraints, alliance and rapport with service providers and staff, and personal factors. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale was used to assess the nature and severity of psychopathology in the past week. Self-reported alcohol and drug use in the past month was assessed with two questions from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team survey (

10 ). Items from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III (

11 ) were used to assess self-reported presence of 14 medical conditions, which ranged from cancer and diabetes to dental and vision problems.

Of 212 inpatients approached, 156 provided informed consent and 56 (26%) refused. Twenty patients were withdrawn from the study because of changes in the discharge plan, participant request, or other reasons (

12 ), leaving a study group of 136 participants. Interviews were completed by trained clinical interviewers between February 2003 and April 2005 during the patient's hospitalization or, for 56 participants, shortly after discharge (9.5±9.9 days). The study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. Additional details concerning participants and methods are available elsewhere (

12 ).

Results

A total of 123 participants were male (90%), 58 were Caucasian (43%), and 78 (57%) were African American. A total of 123 participants (90%) had a high school or equivalent (GED) level of education, and 48 (35%) had a schizophrenia spectrum disorder diagnosis. Psychiatric symptoms ranged from none to mild or moderate (mean±SD total symptoms=2.03±.60). A total of 107 participants (79%) reported at least one current medical condition, with a mean number of medical conditions of 3.53±2.33. Seventy-five participants (55%) reported current vision problems, 58 (43%) dental problems, 54 (40%) high blood pressure, 35 (26%) stomach problems, 33 (24%) skin problems, and 32 (24%) breathing problems.

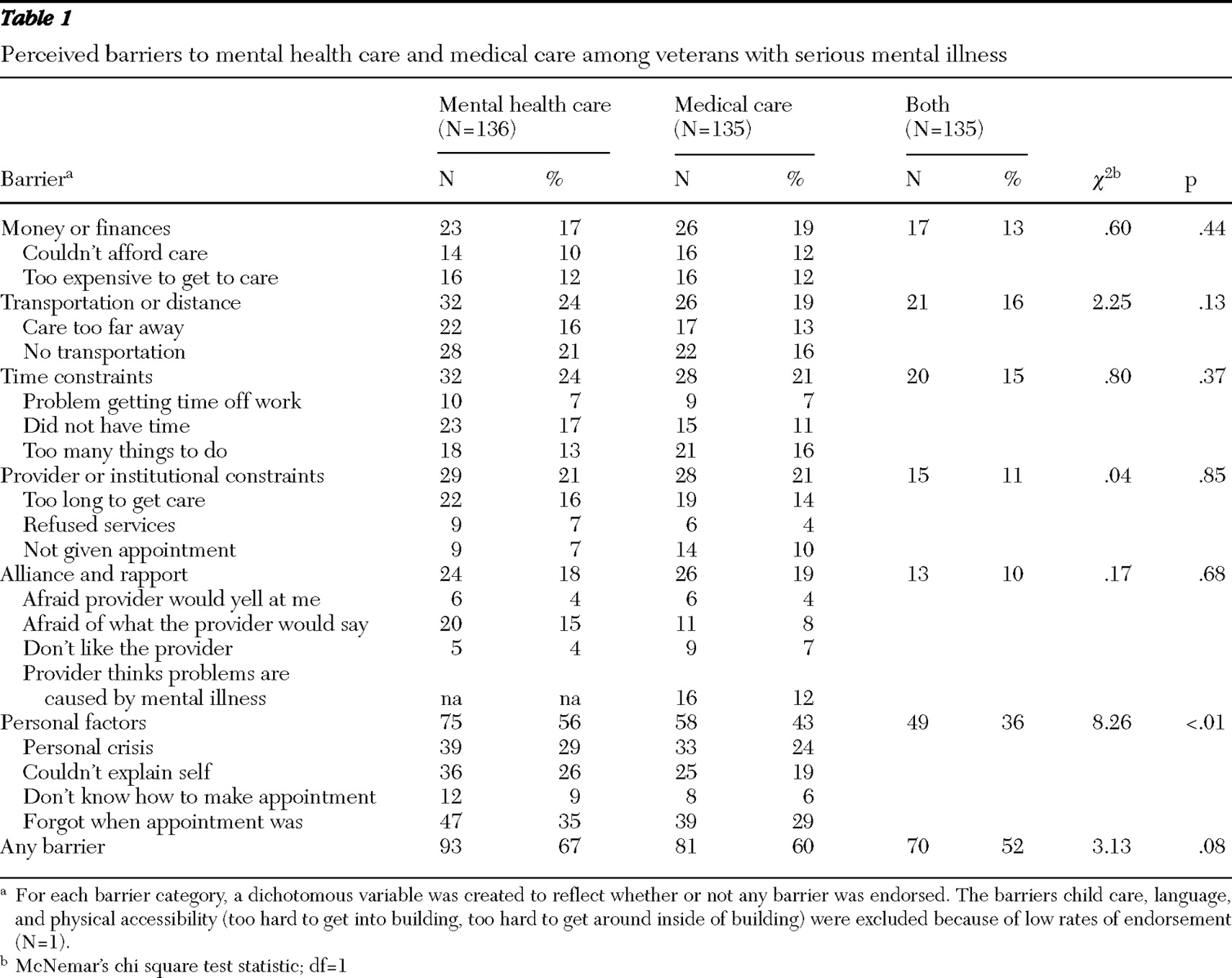

Table 1 summarizes the six identified barriers to accessing mental health care and medical treatment. Sixty-seven percent of participants reported one or more barriers to accessing mental health care (2.47±2.60 barriers), and 60% reported one or more barriers to medical care (2.24±3.03 barriers). Personal factors were the most frequently endorsed barrier to both mental health care (56%) and medical care (43%).

Relationships between demographic and clinical characteristics and perceived barriers were assessed with Spearman's rank-order correlations. Number of barriers to mental health care and number of barriers to medical care, overall and within each barrier category, were summed to determine total number of barriers to each type of care. Older participants were more likely to report fewer alliance- or rapport-related barriers to mental health care (r=–.21, p=.016), whereas married participants reported greater financial barriers (r=.20, p=.022) and more provider constraint barriers (r=.27, p=.002) to medical care. The only association between service-connected disability or monthly income and any barrier to care was that participants receiving benefits for service-connected disabilities and those with a higher monthly income reported fewer perceived transportation and distance barriers to medical care (r=–.20, p=.018, and r=–.18, p=.04, respectively).

Psychiatric symptoms were associated with a significantly greater total number of barriers to mental health care (r=.27, p=.002) and greater financial barriers (r=.21, p=.015), provider constraints (r=.22, p=.011), alliance and rapport problems (r=.23, p=.009), and personal factors (r=.29, p<.001). Similarly, psychiatric symptoms were related to greater total perceived barriers to medical care (r=.26, p=.002) and greater barriers associated with alliance and rapport (r=.26, p=.002) and personal factors (r=.30, p<.001).

Having any medical condition (r=.20, p=.023) and a greater number of medical conditions (r=.27, p=.002) were significantly related to perceived barriers to medical care, both overall and related to alliance or rapport (any condition, r=.20, p=.023; number of conditions, r=.27, p=.002), personal factors (any condition, r=.21, p=.014; number of conditions, r=.31, p<.001), and provider constraint barriers (any condition, r=.22, p=.011; number of conditions, r=.19, p=.025). The only association between medical conditions and barriers to mental health care was that number of medical conditions was related to greater personal factor barriers (r=.22, p=.01). Drug use in the past month was associated with greater provider constraint barriers to mental health care only (r=.18, p=.039). Alcohol use in the past month was not related to any barrier measure.

McNemar's tests of association were calculated to examine the relationship between barriers to mental health care and medical care, overall and within each barrier category. Overall there was no difference in the proportion of participants who reported barriers to mental health treatment and barriers to medical treatment (

Table 1 ). However, the proportion of participants citing personal factors as barriers to mental health care (56%) was significantly greater than the proportion of participants citing personal factors as barriers to medical care (43%). Barriers to mental health care and barriers to medical care were not significantly different for the five remaining barrier categories.

Discussion

Veterans with serious mental illness at risk of treatment dropout perceived a number of barriers to accessing care. Over two-thirds of the veterans in our study reported at least one barrier to mental health care and 60% reported at least one barrier to medical care. Consistent with previous studies of veterans (

3 ), our findings showed that structural barriers and financial barriers were less likely than other barriers to be reported, which may reflect easier access to and greater coverage of clinical care, owing to the structure of the VA health care system (

4 ). Transportation and distance barriers were also relatively low; however, low rates may be an artifact of the exclusion of individuals living more than 50 miles away. In contrast, personal factors were often cited as barriers, particularly with regard to mental health services.

Although most barriers appeared to affect access to medical care and mental health treatment similarly, personal factors were different. Greater perceived barriers associated with personal factors may reflect different attitudes toward mental illness and medical illness. In regard to mental health care, consumers may prefer to solve mental health problems themselves, believe problems will improve without treatment, or view treatment as largely ineffective (

13 ). Moreover, consumers' perceptions of the quality of communication and their relationship with their provider may affect utilization of mental health care (

14 ).

Psychiatric illness may pose one of the most significant barriers to medical and mental health care. We found that more severe psychiatric symptoms were associated with more perceived barriers to medical care and mental health care, both overall and to specific barrier categories. Individuals with serious mental illness generally have fewer financial resources, less stable living situations, and illness-related cognitive and social skills deficits, all of which may affect access to and effective utilization of clinical services. Alternatively, psychiatric symptoms themselves may impede negotiation of the health care system, communication of treatment needs, and advocating for care (

6,

7 ).

Contrary to previous findings, we found few significant relationships between barriers and age. Notably perception of barriers generally has been greater among younger consumers, typically age 30 and under (

3,

13 ), whose numbers were limited in our sample. However, among patients with co-occurring mental disorders and medical conditions, the association with greater perceived barriers to accessing medical care is consistent with earlier studies and may reflect greater dissatisfaction with aspects of consumer-provider communication regarding illness and treatment, which is compounded when dealing with multiple medical conditions (

4 ).

This study was limited by its restriction to veterans with serious mental illness who were hospitalized for psychiatric issues and at risk of treatment dropout. Thus the findings may not generalize to all consumers receiving outpatient mental health care at VA facilities or receiving inpatient or outpatient care in the community. Nevertheless, it provides important information concerning perceived barriers in a particularly vulnerable population at a critical juncture in care. Because our inquiry did not specify barriers to VA or non-VA services, it is unclear if responses reflect access to VA care, non-VA care, or both. However, simultaneous use of VA and non-VA services among those with serious mental illness rarely occurs (

9,

15 ). Finally, because we assessed perceived barriers to clinical care and not actual utilization of services, the extent to which barriers identified by consumers are actually associated with difficulties with, delays in, or lack of receipt of treatment remains unclear. Nevertheless this study suggests that psychiatric symptoms may contribute to barriers among this group, which could affect service use.

Conclusions

Veterans with serious mental illness at risk for treatment dropout perceived barriers to accessing clinical care. Psychiatric symptoms and illness severity may pose one of the most significant barriers to care. Strategies to overcome barriers are needed and should target illness-related factors that may impede service use.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Support for this research was provided by grant VCR02-166 to Dr. Dixon from the Health Services Research and Development Service of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors thank Ye Yang, M.S., for her assistance with data management and analyses.

The authors report no competing interests.