Aims of study

Lifestyle interventions are essential in lowering the risk and morbidity associated with preventable medical conditions (for example, obesity, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes) experienced by adults with serious mental illness. The goal of this study was to provide a systematic literature review of lifestyle interventions tested in the United States aiming to improve the physical health of this at-risk population. To this end, we found 23 studies and focused our review on four key aspects.

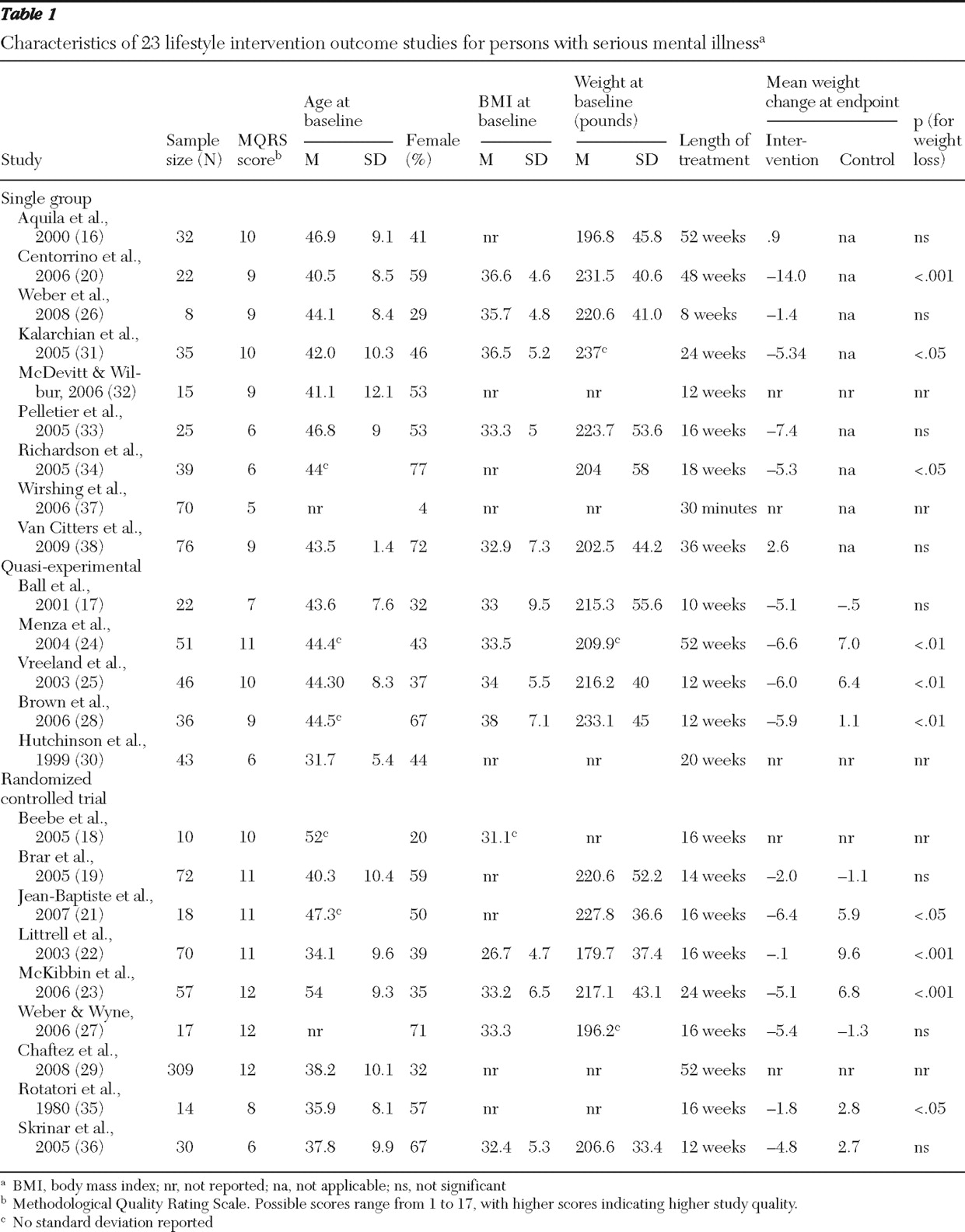

Our first aim was to rate studies' methodological quality. The findings from the MQRS ratings suggest three levels of evidence corresponding to the degree of internal validity of the studies. At the lowest level were the nine uncontrolled studies that relied on single-group pre-post designs. These studies tended to have small sample sizes and to vary in treatment length (treatment length ranged from 30 minutes to 52 weeks). In addition, many of these studies (N=4, 44%) did not use manualized interventions. At the second level of evidence were the five studies that utilized quasi-experimental methods. Similar to the uncontrolled studies in level 1, these quasi-experimental studies consisted of open trials with small samples that varied in treatment length (ten to 52 weeks), and two did not use a manualized intervention. These trials, however, controlled for more threats to internal validity than studies in level 1 by comparing treatment effects between an intervention group and a comparison group (for example, usual care group) and by employing statistical controls to adjust for group differences and minimize selection bias.

At the highest level of methodological quality were the nine randomized controlled trials. These studies ranged in sample size from ten to 309 participants, most used manualized interventions, and treatment ranged from 12 to 52 weeks. A major limitation of these randomized controlled trials was that four did not use blind assessors to measure treatment outcomes, thus introducing the possibility of assessment bias. Future randomized controlled trials in this area should consider using assessors blinded to participants' assignment in order to reduce unintended bias in data collection.

Studies' methodological ratings also suggest that this literature is mostly based on small, single-site efficacy trials, thus limiting the external validity of this evidence to real-world mental health settings. Aside from the study by Chafetz and colleagues (

29 ), the studies had small samples ranging from eight to 76 participants. Moreover, most studies were single-site trials, usually in academic settings, limiting the generalizability of these findings to community settings that have limited resources and infrastructure to support these interventions. Finally, the small number of persons from racial and ethnic minority groups included in these studies restricts the generalizability of their results to diverse populations. These methodological findings suggest that more rigorous methods are needed to advance the knowledge base in this area, particularly multisite randomized controlled trials that include racially and ethnically diverse samples and are conducted in collaboration with providers and organizations outside the confines of academic institutions.

Our second aim was to examine intervention characteristics. Across the studies reviewed, goals of the interventions were to enhance participants' knowledge of nutrition, physical activity, and general health promotion; to impart skills regarding healthy eating, weight management, and exercise; and to provide support for sustaining lifestyle behavioral changes. Twelve studies reported statistically significant improvements in either weight loss or metabolic syndrome risk factors associated with their lifestyle interventions. These interventions for individuals with serious mental illness were informed and adapted from existing lifestyle interventions originally developed and used in the general population. All used a group format or a combination of group and individual sessions to deliver the intervention. Similar to the approaches proven effective in the general population for reducing weight (

40,

41 ) and decreasing risk factors for chronic medical conditions, such as hypertension and diabetes (

39,

42 ), most interventions used dietary counseling and an exercise regimen of light-to-moderate physical activity (for example, walking). Finally, all of these studies incorporated common behavioral techniques (for example, problem solving, goal setting, and self-monitoring) into their interventions. It is difficult to tease out from the existing studies which of these intervention features accounted for the greatest variance in health outcomes for individuals with serious mental illness because of the differences in samples, sites, and outcome measures used across studies. Findings of this nature make inferences untenable. More work in this area is needed to identify the core intervention elements that are most beneficial and cost-effective for improving the health of persons with serious mental illness.

Our third aim was to examine the effects that lifestyle interventions had on health outcomes, particularly weight loss and risk factors for preventable medical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Both types of outcomes are important health indicators for individuals with mental illnesses because they are linked to the elevated mortality and morbidity reported in this population (

43 ).

Ten of the 18 studies that reported data on weight loss found statistically significant reductions in weight associated with receiving a structured lifestyle intervention. However, the average weight loss in these ten studies varied by study design. The mean weight loss for the three single-group studies (

20,

31,

24 ) was 8.2±5 pounds, whereas the three quasi-experimental studies (

24,

25,

28 ) and four randomized controlled trials (

21,

22,

23,

35 ) showed more modest average weight loss (6.2±.4 pounds and 3.4±2.9 pounds, respectively). The mean for the randomized controlled trials reviewed falls below the mean weight loss reported in meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of lifestyle interventions tested in the general population, which was eight to 11 pounds (

44,

45 ). The difference in weight loss outcomes between the general population and persons with serious mental illness may be due to variability in treatment intensity, worse health status at baseline among persons with serious mental illness, or methodological differences across studies. Our review shows that persons with serious mental illness may benefit from lifestyle interventions, although possibly to a lesser extent than the general population, but variability in study design and rigor limits the identification of the most beneficial interventions for achieving weight loss in this at-risk population. More research in this area is warranted to understand and enhance the weight loss outcomes of lifestyle interventions for individuals with serious mental illness.

Seven of the 13 studies that examined the benefits of lifestyle interventions on metabolic syndrome risk factors had statistically significant findings. These seven studies used a range of methodologies. Two were single-group studies (

20,

28 ), two were quasi-experimental studies (

24,

28 ), and three were randomized controlled trials (

19,

21,

23 ). These studies reported positive effects on sBP and dBP, blood glucose and triglyceride levels, and central adiposity. Methodological variability among these studies prevented us from identifying the most effective interventions for reducing the risk of metabolic syndrome among persons with serious mental illness. Even though these risk factors were secondary outcomes and only a limited number of studies explored these effects, these findings seem promising because improvements in these risk factors may exert a bigger health benefit than weight loss (

46 ). Because of the high prevalence of obesity and chronic medical illnesses among persons with serious mental illness and the negative metabolic alterations associated with second-generation antipsychotics (

43,

47 ), future trials need to be properly powered to examine the effect of lifestyle interventions on these risk factors.

Our fourth and last aim was to examine the inclusion of persons from racial and ethnic minority groups in these studies and the cultural and linguistic adaptations of these interventions. Our findings show a serious underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minorities in the studies reviewed, particularly for Hispanics, Asian Americans, and the non-English-speaking populations in the United States. There is also a true neglect of cultural and linguistic issues within this literature. Only one study included non-English-speaking participants and culturally adapted the lifestyle intervention to fit the needs of a small group of Spanish-speaking Hispanic patients (

26 ). Aside from Weber and colleagues' study (

26 ), we know of one other quasi-experimental study that was recently completed that also adapted a lifestyle intervention for Hispanic outpatients with serious mental illness (

48 ). More work in this area is clearly needed given the prevalence of racial and ethnic health disparities in the United States (

49 ).

Linguistic and cultural adaptations are essential to make lifestyle interventions relevant and effective for persons from racial and ethnic minority groups. The most basic level of cultural sensitivity is to provide the intervention and its materials in the dominant language of the target group (

50 ). Linguistic accessibility is essential to achieve cultural competence, but it is not sufficient. Attention to linguistic strategies alone could create a situation in which access to a lifestyle intervention is improved but the approach and content of the intervention is incongruent with patients' cultural norms, values, and preferences, which makes the intervention culturally inappropriate and ineffective (

51 ). For instance, diet is inherently cultural. A lifestyle intervention that presents dietary options that are in conflict with participants' cultural traditions and their socioeconomic reality in regard to food choices and meal preparation will most likely result in resistance to dietary changes and dropout from the program. In addition, ideal body image varies across cultures, with some African-American and Hispanic groups favoring a fuller body ideal (

52,

53 ). Unaddressed, this can lead to the perception among participants that the lifestyle intervention is insensitive or even racist. Attention to key cultural elements that have an impact on lifestyle intervention, such as diet, exercise, body image, and health promotion need to be carefully considered in order to make interventions culturally appropriate. This can also enhance treatment engagement, retention, and ultimately physical health outcomes. More work in this area is needed to identify which intervention elements require cultural adaptation and to test the efficacy of these interventions with minority populations.