Recent mortality statistics for patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder indicate a 1.2- to 4.9-fold increase in mortality relative to age- and sex-matched individuals in the general population resulting from coronary heart disease, diabetes, stroke, and other cardiovascular conditions (

1 ). Moreover, the lifespan of public mental health patients is approximately 25 years shorter than that of the general population (

1 ). In the recent Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial, the ten-year coronary heart disease risk was significantly higher among patients with schizophrenia (men, 9.4%; women, 6.3%) than in a general U.S. population sample (men, 7.0%; women, 4.2%) (p<.001) (

2 ). A variety of lifestyle factors, including smoking (

3,

4,

5 ), lack of physical activity (

3 ), and poor diet (

3,

6,

7 ), contribute to the development of cardiovascular risk factors. Patients with serious mental illness have elevated rates of metabolic syndrome (

8,

9 ). In the fasting subsample of the CATIE study (N=689) the prevalence of metabolic syndrome, based on the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) definition, was 40.9% among patients with chronic schizophrenia (

8 ). Elevated rates of metabolic syndrome have also been reported among patients with bipolar disorder, varying between 17% and 50% (

10,

11,

12 ). In addition to lifestyle and illness-related factors, the use of some second-generation antipsychotics may also contribute to the increased cardiometabolic risk (

13,

14,

15,

16 ).

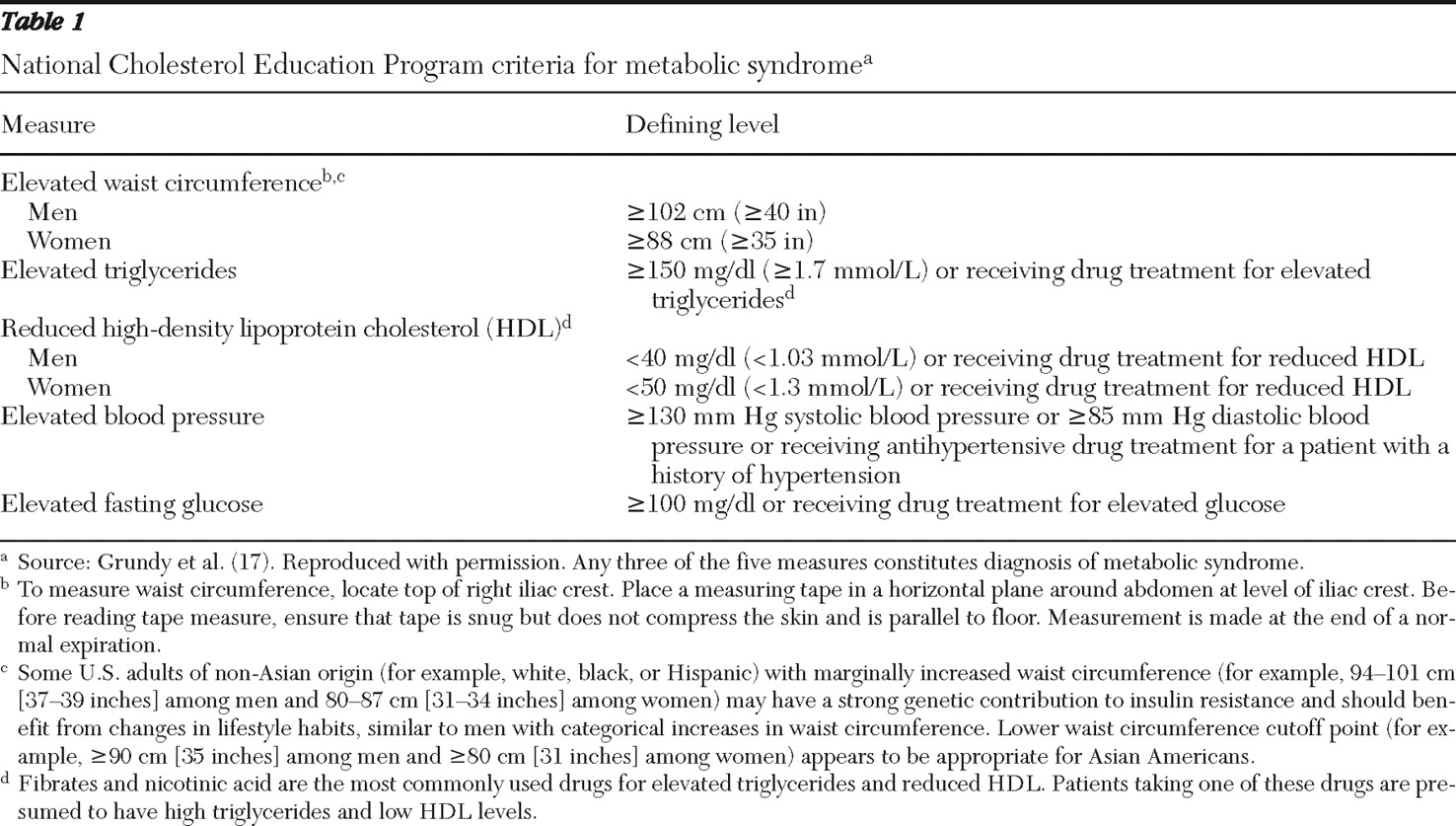

The metabolic syndrome is one of the most widely used markers for cardiometabolic risk in the general population. According to the NCEP (

Table 1 ), metabolic syndrome is defined as abdominal obesity; low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL); and elevated triglycerides, blood pressure, and fasting glucose (

17 ). A recent meta-analysis of longitudinal studies reporting associations between metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular events or mortality demonstrated that metabolic syndrome is an independent predictor (relative risk [RR]=1.78) of cardiovascular events and death (

18 ). A similar ten-year RR estimate has been reported for metabolic syndrome among patients with mixed psychiatric disorders who were receiving second-generation antipsychotics (

19 ).

The reduction of modifiable risks of cardiovascular disease has been the focus of broadscale national health improvement efforts in the general population (

20,

21,

22 ). Recent declines in mortality resulting from cardiovascular disease point to the success of such efforts in the general population (

23 ). However, it appears that cardiovascular risks have remained high and secondary preventive efforts have remained insufficient among patients with severe mental illness (

24,

25 ). Although cardiometabolic screening has been widely recommended for patients given prescriptions for second-generation antipsychotics (

26,

27,

28 ), prevalence estimates of cardiovascular risk and metabolic syndrome have generally not been obtained outside of clinical trials, and data are lacking for the prevalence and severity of metabolic abnormalities among psychiatric patients treated in routine clinical settings.

A national comprehensive cardiometabolic screening program for patients in a variety of public mental health facilities, group practices, and community behavioral health clinics was initiated in 2005 with the aim of obtaining naturalistic data documenting the prevalence and severity of metabolic abnormalities among patients with psychiatric illnesses.

Methods

Study population and screening

Between 2005 and 2008, one-day, voluntary metabolic health fairs funded by Pfizer Inc. offered outpatients with mental illness free metabolic screening and same-day feedback to treating physicians from a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant biometrics testing third party (Impact Health, King of Prussia, Pennsylvania). Advertisements for the health fair were posted in clinics, and patients who attended a scheduled outpatient appointment on the day of the health fair were invited to receive voluntary cardiometabolic screening. Informed consent was obtained for all participants.

Clinics were identified through the National Council for Community Behavioral Healthcare. Sites included community mental health centers, prisons, state hospitals, inpatient units, and Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care facilities. This article focuses on patients with a self-reported diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or depression. The first 10,111 patients were sampled. However, 15 patients without data on sex and 12 patients without metabolic data to determine metabolic syndrome were excluded, giving us a final sample of 10,084 patients at 219 sites (median 39 patients per center; range=4–166). [An appendix showing the number of patients sampled at each site and in each state is available as an online supplement at

ps.psychiatryonline.org .]

The standardized screening, performed by a trained health technician, included a questionnaire (to collect medical history), physical examination (waist circumference, body mass index [BMI], and blood pressure), and laboratory testing of fasting or nonfasting lipid profile (total cholesterol, HDL, low-density lipoprotein [LDL], and triglycerides) and of blood glucose.

Statistical analysis

Means, medians, and interquartile ranges (25th and 75th percentiles) were used, with the latter being used because of skewed data. Separate analyses were conducted for the 2,739 patients who indicated that they were fasting. Metabolic abnormalities and the metabolic syndrome were defined according to NCEP criteria (

Table 1 ). Patient records were deidentified in accordance with HIPAA privacy rules, and Emory University exempted research on the data set from institutional review board review. Descriptive statistics were used for continuous and categorical cardiometabolic endpoints of interest. Patients without values for all five factors but who met at least three metabolic syndrome criteria were categorized as having metabolic syndrome. Patients who could not possibly achieve three risk factors on the basis of the pattern of available and missing values were categorized as not having metabolic syndrome. Patients whose patterns of available and missing values could not be used to determine metabolic syndrome status were not assigned any status. Rates of metabolic abnormalities were examined among participants who self-reported diagnoses of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia (with the caveat that these two diagnoses were not mutually exclusive and were comorbid among 337 of the 2,739 fasting participants).

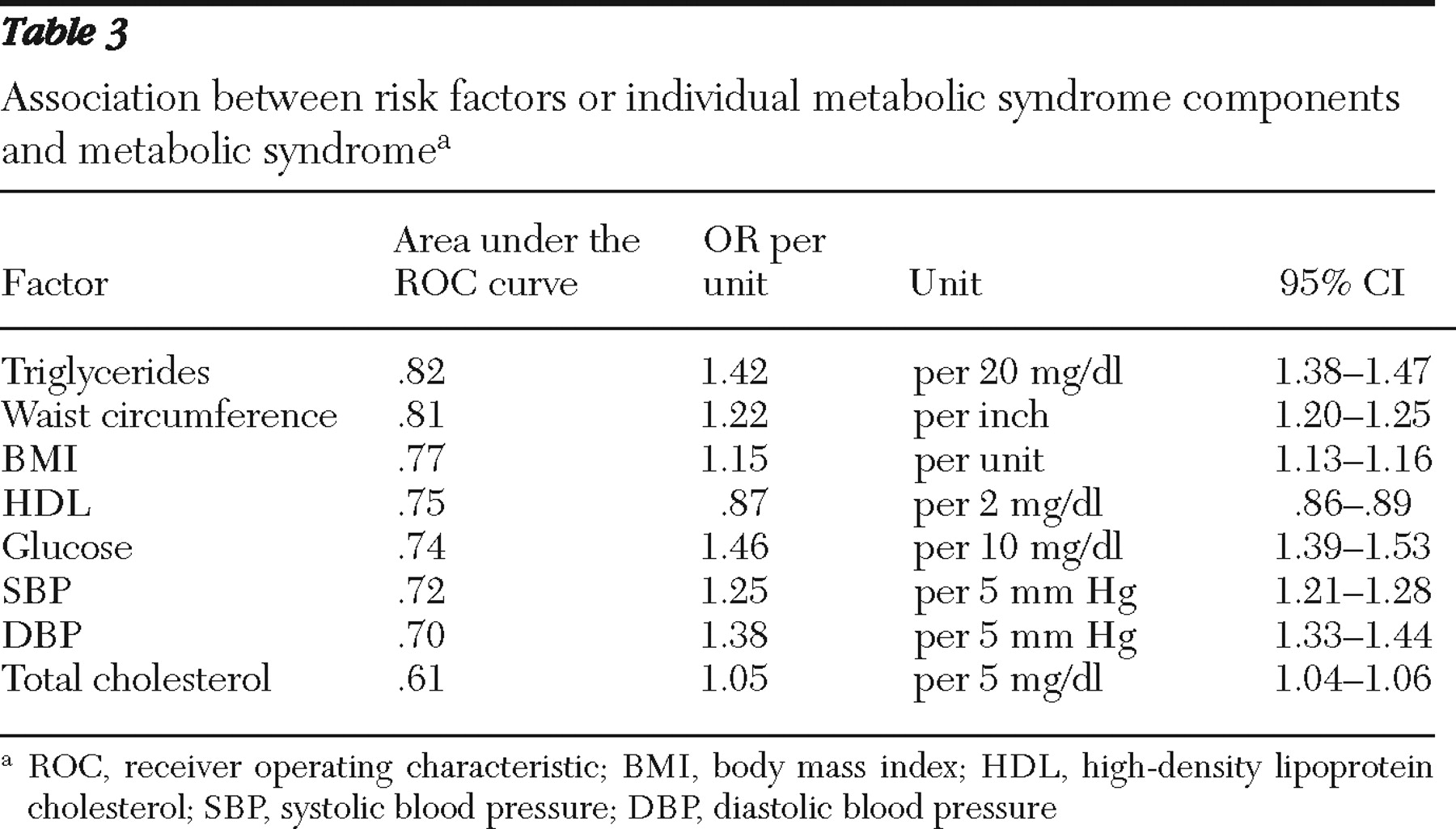

Logistic regression was performed to evaluate the significance of an association between individual risk factors and metabolic syndrome. Area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to evaluate individual risk factors among patients classified into groups according to whether or not they had metabolic syndrome (

29 ). The ROC curve plots the sensitivity (proportion of true positive) versus 1 - specificity (proportion of false positive) of the metabolic syndrome classification by a risk factor, with higher areas under this curve indicating better classification. In general, a classifier needs to produce an area under the curve value higher than .7 for acceptable discriminating power.

Results

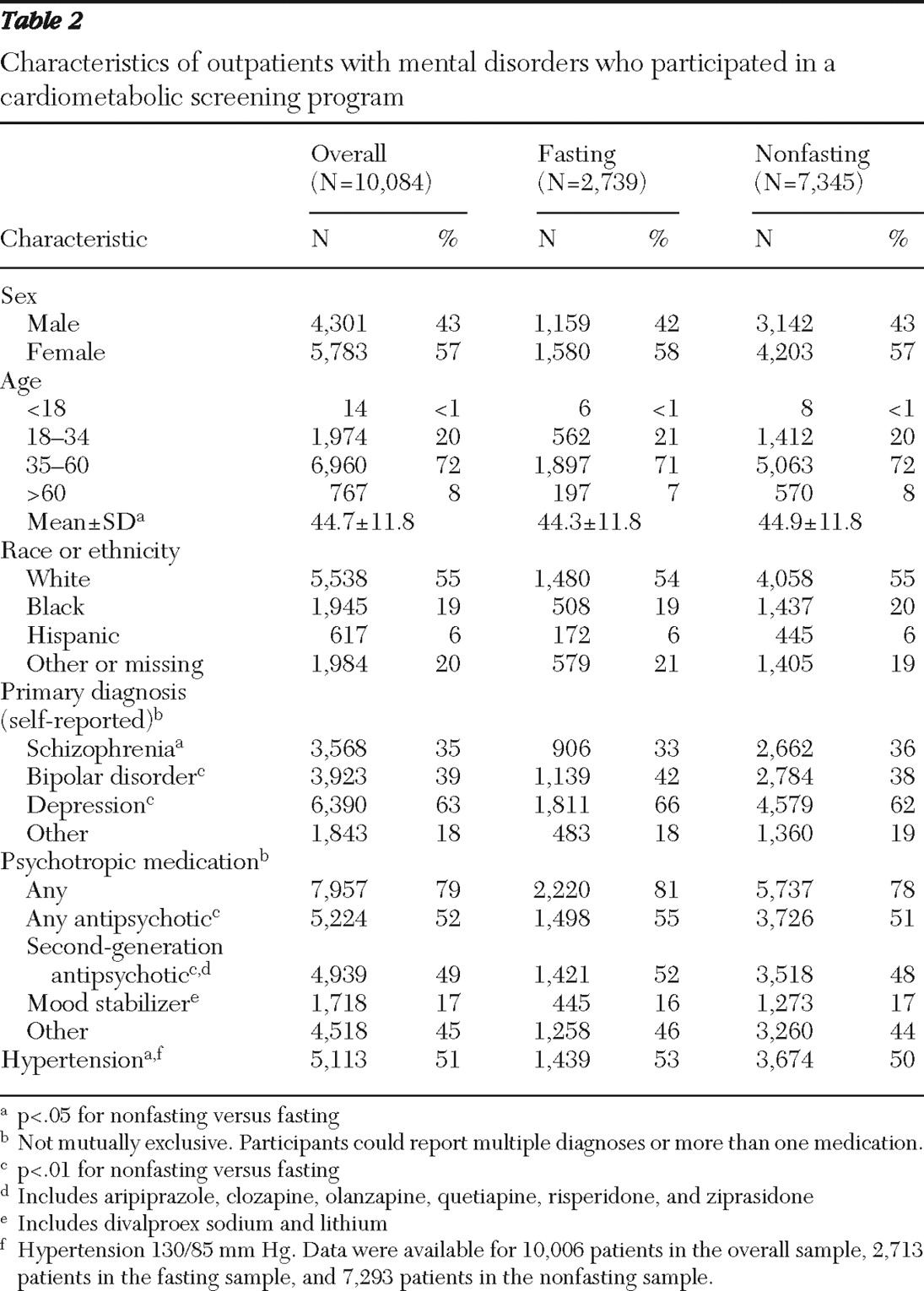

Overall analyses included 10,084 outpatients with mental illness, 6,233 of whom reported having a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or both. The fasting sample included a subset of 2,739 patients. Patient demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in

Table 2 . The fasting and nonfasting samples were similar, with some small differences that reached statistical significance, mainly because of the large sample size. For example, the small difference in age of half a year was significant (p=.03). The largest percentage point difference between groups was 4% for bipolar disorder, depression, and the use of second-generation antipsychotics.

Metabolic syndrome in the fasting sample

Altogether, 52% (1,359 of 2,633) of the fasting sample demonstrated evidence of metabolic syndrome. Among the 2,466 patients with data on all five risk factors, 92% (N=2,281) fulfilled at least one criterion for metabolic syndrome, and two or more risk factors for metabolic syndrome were observed among 71% (736 of 1,035) of male patients and 77% (1,109 of 1,431) of female patients. Among male patients, 23% (243 of 1,035), 17% (177 of 1,035), and 6% (63 of 1,035) had three, four, and five risk factors, respectively. Among female patients, 27% (382 of 1,431), 19% (274 of 1,431), and 8% (108 of 1,431) had three, four, and five risk factors, respectively. Overall, 471 participants were not able to be classified as having or not having metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome was present among 54% (588 of 1,093) of patients with bipolar disorder and 52% (450 of 871) of patients with schizophrenia. Triglyceride levels were the best predictor of metabolic syndrome, as measured by the area under the ROC curve, followed closely by waist circumference (

Table 3 ).

BMI and waist circumference in the overall sample

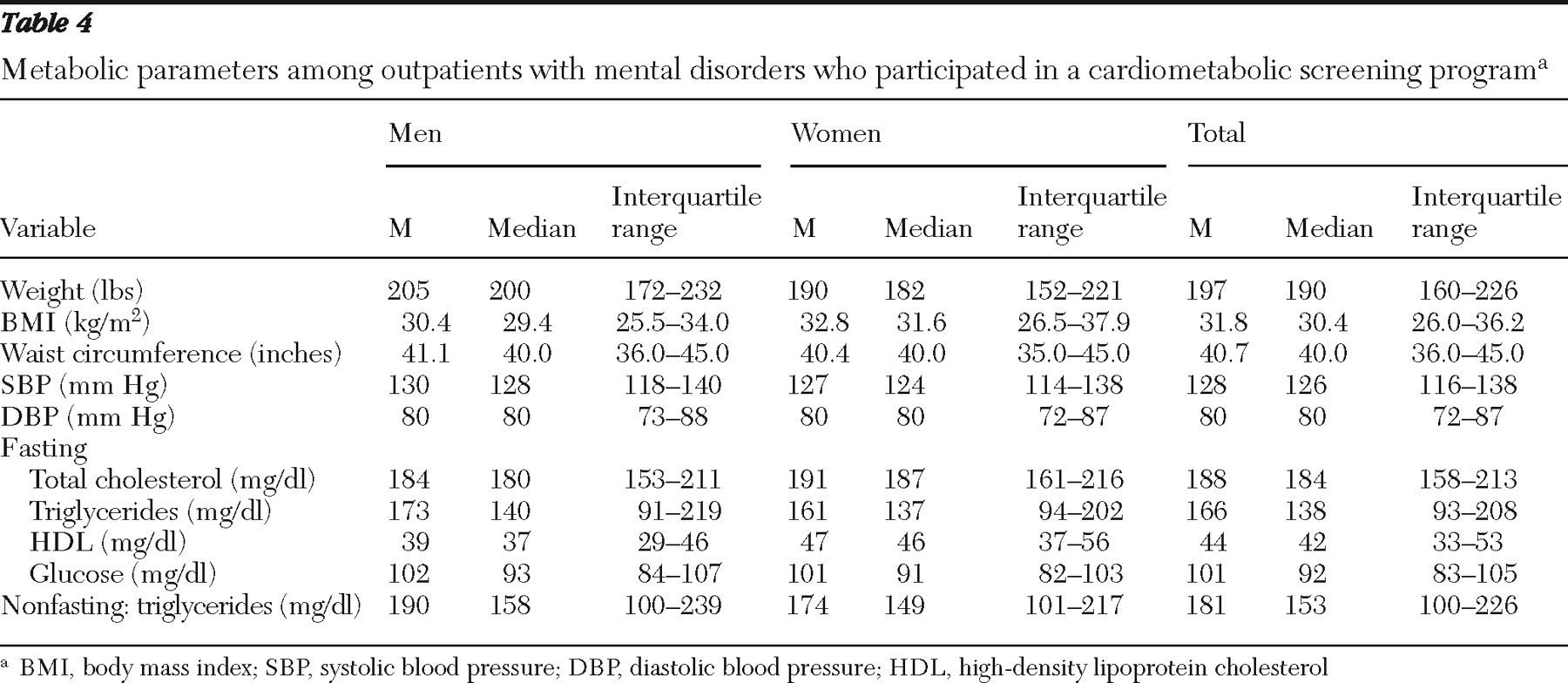

Data for weight, BMI, and waist circumference are displayed in

Table 4 . There were high prevalence rates of overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m

2 ) (men, 32% [1,375 of 4,269]; women, 24% [1,361 of 5,710]; overall sample, 27% [2,736 of 9,979]; persons with schizophrenia, 29% [1,014 of 3,545]; and persons with bipolar disorder, 27% [1,054 of 3,898]). There were also high prevalence rates of obesity (BMI ≥30.0 kg/m

2 ) (men, 46% [1,945 of 4,269]; women, 57% [3,268 of 5,710]; overall sample, 52% [5,213 of 9,979]; persons with schizophrenia, 53% [1,869 of 3,545]; and persons with bipolar disorder, 55% [2,136 of 3,898]).

Blood pressure in the overall sample

Blood pressure data are displayed in

Table 4 . Hypertension was present among 51% (5,113 of 10,006) of the overall sample, 55% (2,341 of 4,274) of men, 48% (2,772 of 5,732) of women, 51% (1,798 of 3,546) of patients with schizophrenia, and 51% (1,969 of 3,895) of patients with bipolar disorder.

Lipid and glucose profiles

Overall sample. Lipid and glucose values are displayed in

Table 4 . In the overall sample, hypertriglyceridemia (≥150 mg/dl) was found among 53% (2,222 of 4,161) of men, 50% (2,818 of 5,638) of women, and 51% (5,040 of 9,799) of the total population.

Fasting sample. Hypercholesterolemia (≥200 mg/dl) was present among 32% (367 of 1,130) of men, 38% (585 of 1,559) of women, and 35% (952 of 2,689) of the overall fasting population. Low HDL levels were present among 57% of men (636 of 1,107), 61% (936 of 1,544) of women, and 59% (1,572 of 2,651) of the overall fasting population. Hypertriglyceridemia (≥150 mg/dl) was present among 46% of men (520 of 1,125), 44% (685 of 1,544) of women, and 45% (1,205 of 2,669) of the overall population. In the fasting population, several patients had hyperglycemia: 33% (880 of 2,668) had glucose levels ≥100 mg/dl and 20% (539 of 2,668) had glucose levels ≥110 mg/dl (≥100 mg/dl was the new definition of hyperglycemia and ≥110 mg/dl was the old definition [17]). Among men, 36% (403 of 1,124) had glucose levels ≥100 mg/dl and 22% (242 of 1,124) had glucose levels ≥110 mg/dl; among women, the values were 31% (477 of 1,544) and 19% (297 of 1,544), respectively.

Among fasting patients with bipolar disorder, 48% (537 of 1,109) had hypertriglyceridemia, compared with 40% (354 of 878) of patients with schizophrenia. Fasting hyperglycemia (≥100 mg/dl) was present among 31% (347 of 1,107) of patients with bipolar disorder and 37% (323 of 882) of patients with schizophrenia. Hypercholesterolemia was found among 36% (405 of 1,115) of patients with bipolar disorder and 30% (264 of 891) of patients with schizophrenia. Low HDL levels were found among 61% (673 of 1,102) of patients with bipolar disorder and 59% (523 of 879) of patients with schizophrenia.

In the fasting sample, 11% (296 of 2,739) of patients had a severe metabolic or blood pressure abnormality—that is, glucose ≥300 mg/dl, total cholesterol ≥600 mg/dl, triglycerides ≥600 mg/dl, or blood pressure ≥160/100 mm Hg.

Lack of treatment for self-reported disorders

Among the 3,732 patients (37%) in the overall sample who reported having been told that they had high cholesterol, 59% (N=2,215) reported receiving no treatment for this condition (60% [912 of 1,527] of patients with bipolar disorder and 57% [781 of 1,359] of patients with schizophrenia). Among the 1,754 (17%) who reported having been told they had diabetes, 699 (40%) reported not receiving antihyperglycemic treatment (40% [286 of 713] of patients with bipolar disorder and 41% [309 of 748] of patients with schizophrenia). Similarly, among the 3,608 (36%) patients with self-reported hypertension, 1,646 (46%) reported not receiving antihypertensive medication, with similar rates in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia (48% [726 of 1,507] of patients with bipolar disorder and 49% [654 of 1,341] of patients with schizophrenia). In the fasting sample, 60% (819 of 1,359) of patients with metabolic syndrome were not receiving treatment for any metabolic syndrome component (62% [365 of 588] of patients with bipolar disorder and 56% [253 of 450] of patients with schizophrenia).

Degree of control over self-reported disorders

In the fasting sample, 33% (132 of 406) of patients reporting a diagnosis of hypercholesterolemia and treatment with cholesterol-lowering medication had total cholesterol levels ≥200 mg/dl, and 65% (255 of 395) maintained low HDL levels. Among the 242 fasting patients reporting diagnosis and treatment of diabetes, 69% (N=167) had glucose levels ≥100 mg/dl and 44% (N=106) had levels ≥126 mg/dl. Among the 510 fasting patients reporting diagnosis and treatment of high blood pressure, 71% (N=361) continued to be hypertensive. Among the 1,946 patients from the total sample who reported taking antihypertensive medications, 65% (N=1,268) remained hypertensive.

Discussion

This study is, to our knowledge, the largest survey of cardiometabolic risk factors and metabolic syndrome among persons with psychiatric disorders. The overwhelming majority (79%) of patients were overweight or obese (BMI ≥25.0). Because of the central role of BMI in cardiometabolic disease, medical and behavioral interventions promoting weight loss should become part of routine care in this population. In contrast to other metabolic parameters, BMI measurements can be obtained easily and might represent a simple metric for assessing the integration of medical and behavioral health services by mental health centers. Moreover, 92% of patients had at least one metabolic syndrome-related risk factor, and 52% of fasting patients met criteria for metabolic syndrome. In line with prior research (

30 ), hypertriglyceridemia and abdominal obesity predicted metabolic syndrome better than other metabolic syndrome components.

These findings are disturbing, because metabolic syndrome increases risk of both cardiovascular disease and diabetes (

31 ). A notable proportion of patients in the fasting sample (11% [296 of 2,739]) had a severe metabolic abnormality (glucose ≥300 mg/dl, total cholesterol ≥600 mg/dl, triglycerides ≥600 mg/dl, or hypertension ≥160/100 mm Hg), indicating the need for immediate medical intervention (

21,

32,

33 ). However, among patients who reported having been told they had hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, or diabetes, only 41%, 54%, and 60%, respectively, reported receiving any specific medical treatment for these conditions. In the fasting subsample, only 40% of patients with metabolic syndrome reported receiving medical treatment for any metabolic syndrome component. It is important to note that a large proportion of patients who reported receiving medical treatment continued having medically relevant abnormalities (hypercholesterolemia, 33%; hypertension, 71%; low HDL levels, 65%; and hyperglycemia: 69%).

These results confirm prior reports of significant rates of undertreatment and lack of treatment for comorbid medical conditions among patients with severe mental illness (

34,

35,

36,

37,

38 ). In the CATIE study, 88% of patients with schizophrenia and dyslipidemia were not receiving lipid-lowering therapy. Similarly, 30% of patients with schizophrenia and diabetes and 62% of those with hypertension were untreated for these conditions (

35 ). In another study, 62% of patients treated with second-generation antipsychotics who had elevated LDL levels did not receive a medical consult or treatment, despite the fact that they were inpatients (

37 ).

Taken together, our findings from a large sample (nearly seven times the size of the CATIE study) with diverse representation indicate that the high rates and insufficient treatment of metabolic problems are common in real-world treatment settings. Compared with estimates from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (

39 ), our sample had only slightly more women (57% [5,790 of 10,084] versus 51%) and fewer whites (55% [5,546 of 10,084] versus 62%) and was within the age range of the majority of community mental health center patients (18–64 years) (8,40).

A variety of barriers appear to limit the ability of clinicians to effectively monitor psychiatric patients in accordance with published treatment guidelines (

28,

41 ). Patients with a high likelihood of unhealthy lifestyle behaviors (

3,

5,

6,

24,

25 ) may lack clear direction regarding methods to improve their metabolic risk. The metabolic complications of treatment with some of the currently available antipsychotics add to the problem (

13,

14,

15,

16 ). Among mental health providers, barriers include lack of comfort with medical issues or lack of time and resources to address physical health issues (

42,

43,

44 ). Furthermore, mental health facilities are not equipped to provide full medical care and have limited ability to coordinate off-site care (

39,

45 ).

Although this study provides data on a large and diverse set of patients with mental illness, it has several methodological limitations. Patients volunteering for this screening program may have been more concerned about their health, had better health information available to them, or had higher overall functioning than nonvolunteers; caregivers or physicians may have also encouraged participants to attend. If true, the findings presented here are all the more troubling, because patients with less concern for their health or lower functioning may have even worse medical health status and outcomes. Alternatively, it may be that patients who did not volunteer were of normal weight and therefore were not encouraged by a physician or caregiver to attend a screening, which would bias the selection as well. Some of the information collected relied on self-report by patients, including diagnosis, medications, and fasting status, which might have affected the results. Furthermore, analyses were not adjusted for duration and severity of illness or treatment with specific medications.

Conclusions

Our findings underscore the need to enhance physician-patient communication regarding metabolic risk factors and to increase adherence to existing treatment and monitoring guidelines (

28 ). Several monitoring initiatives have been reported, including the continuity of care model (

46 ). Primary prevention, a public health strategy involving the identification of a high-risk population with the goal of preventing disease, may assist in identifying patients in need of treatment (

47 ). Given the results of the study presented here indicating the association between waist circumference and metabolic syndrome (

30 ), this would be a simple and relevant measurement for clinicians to obtain. Similarly, weight gain during the first six weeks of treatment with a second-generation antipsychotic (olanzapine) has been associated with significant weight gain over the first year of treatment (

48 ), making early weight gain an even easier measure that should be tracked to make early treatment adjustments. Because several data sets have shown that guidelines alone do not lead to an adequate level of monitoring of (

38,

39,

41,

42,

49,

50 ) and interventions for (

37,

38 ) cardiometabolic risk factors among patients with severe mental illness, mental health providers, patients, and families need to be educated and medical monitoring and management need to be an integral part of treating patients with severe mental illness. Future studies should investigate the effectiveness of various education models and dissemination practices of clinical tools. Moreover, the potential impact on prescriber behavior of local and regional policy changes, such as use of health monitoring as an explicit marker of quality control and reimbursement, should be investigated.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Funding for this study was provided by Pfizer Inc. Annie Neild, Ph.D., of PAREXEL, served as scientific writer and provided editorial support. Her work was funded by Pfizer Inc. The role of the scientific writer was to draft an initial briefing document and then to coordinate discussions between authors, incorporate author comments on drafts, and ensure version control, as well as compliance with journal style and author guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

Dr. Correll has received speaker or consultancy honoraria from Actelion, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffmann-La Roche, Janssen, Lundbeck, Medicure, Otsuka, Pfizer, Schering-Plough, Supernus, Takeda, and Vanda. Dr. Lombardo, Dr. O'Gorman, Dr. Harnett, Ms. Sanders, Dr. Alvir, and Dr. Cuffell are stockholders, as well as employees, of Pfizer Inc. Dr. Druss reports no competing interests.