Getting access to offspring

We were able to gather information on the fate of 93 of the 158 patients who were parents. It was more difficult to locate patients with a history of homelessness, alcohol or drug abuse, or antisocial personality disorder. Our ability to locate patients was not related to whether the patient had ever lived with his or her offspring or whether the offspring had ever been placed in foster care.

From the pool of 93 subjects who could be relocated on follow-up, we eliminated patients with underage offspring and patients who had moved outside the region, who were currently hospitalized, or who were deceased. Of the remaining 68 patients who could be asked for permission to contact their offspring, 41, or 60 percent, agreed, and 27, or 40 percent, refused. We noted no differences in participation based on whether the patient had ever lived with his or her children, had ever been homeless, or had a child placed in foster care.

Characteristics of offspring

Demographic characteristics.

When we contacted the offspring of the 41 consenting parents, 39 (95 percent) agreed to be interviewed and two refused. Thirty-six of the 39 offspring who were interviewed (92 percent) were children of women patients.

Offspring were primarily female (29 offspring, or 74 percent), American born (37 offspring, or 95 percent), and raised in New York City (32 offspring, or 82 percent). The majority were members of a minority group: 23 were African American (59 percent), and 15 were Hispanic (38 percent). Most indicated that their religious preference was Protestant (17 offspring, or 44 percent) or Catholic (11 offspring, or 28 percent).

The age range was 13 to 48 years, and the median age was 26 years. More than two-thirds were single (27 offspring, or 69 percent), but nearly one-fifth were married or living with a partner (seven offspring, or 18 percent). Fourteen offspring, or 36 percent, had one child, and nearly one-fourth (nine offspring, or 23 percent) had two or more children. Only two offspring had ever served in the military.

The median level of education was 12 years, but nearly half had attended college. The majority (22 offspring, or 61 percent) were employed full or part time. The apparent success in educational endeavors for the group as a whole occurred even though a substantial minority had dropped out of high school (nine offspring, or 23 percent), were left back a grade (11 offspring, or 28 percent), were suspended from school (12 offspring, or 31 percent), or were often truant (14 offspring, or 36 percent). Only three offspring—two sons and one daughter—had ever spent time in prison or jail.

Childhood experiences.

Nearly all offspring were raised by the patient-parent for some time from birth to 18 years of age. However, changes in childhood living settings and relationships with nurturing adults were common. Only three offspring, or 8 percent, experienced no such changes. The offspring were raised in an average of three different settings, with a range from one to seven settings. Residential instability was typically associated with the patient's inability to care for offspring, precipitating foster care placement for ten offspring, or 29 percent, or care by relatives for 18 offspring, or 51 percent.

Corporal punishment was common in the settings in which offspring were raised. About half of the offspring (21 respondents, or 54 percent) reported having been hit with a belt, stick, or fist, and six offspring (15 percent) stated that they had been bruised or beaten. There were no gender differences in these reports. Eight subjects (21 percent) reported that they were raised in a setting in which one or more children was physically injured or sexually abused by a parent or adult in the household. For two offspring, the abuse was severe enough to have resulted in a child's being removed from the home by civil authorities. Only three offspring, or 8 percent, indicated that they had ever run away from home.

Experiences with parents with mental illness.

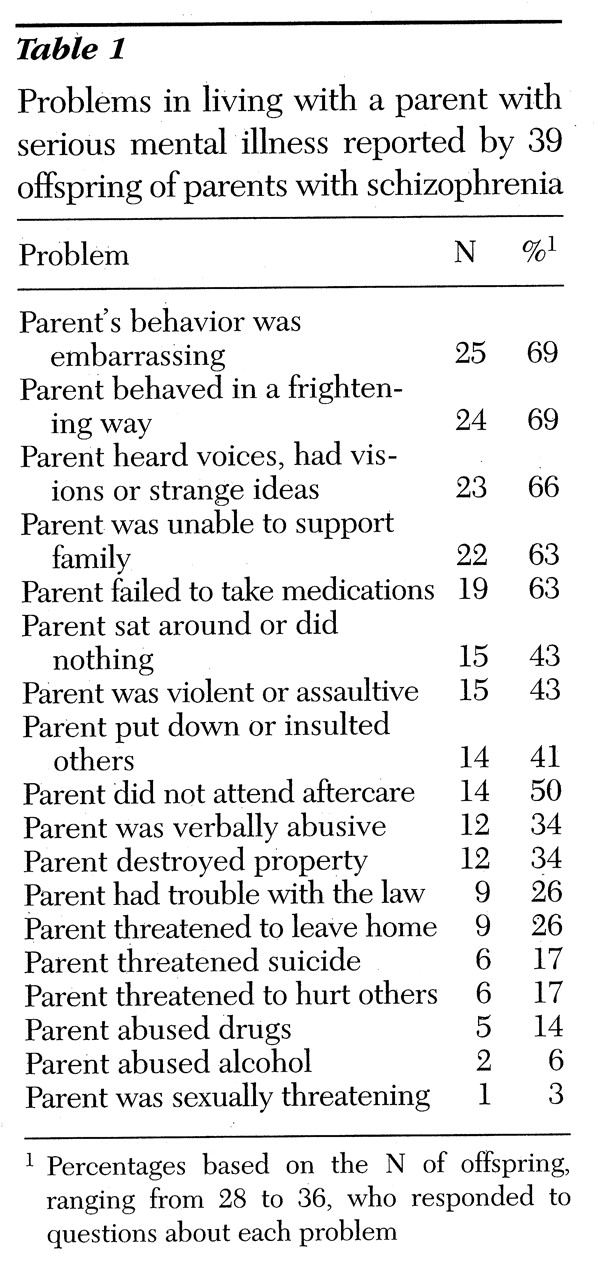

The offspring reported many problems in living with their parent who was a patient, even though they lived together intermittently. Evaluating their overall experience, more than three-quarters reported some problems with their parent (30 offspring, or 77 percent), and 21 offspring (54 percent) stated that there were many problems or serious problems. When asked about the most common problems, half or more of the offspring indicated that the parent's behavior was embarrassing or that the parent behaved in a frightening way, heard voices or had visions or strange ideas, was unable to support the family, or failed to take medications. Other common problems were that the parent sat around and did nothing all day, was violent or assaultive, put down or insulted others, and failed to attend aftercare. A list of these problems from most to least often reported is shown in

Table 1.

Although all of the offspring we interviewed were aware that their parent suffered from a disabling emotional illness, their level of knowledge, attitudes, and specific experiences related to the disorder varied considerably. Only half (19 offspring, or 49 percent) had ever had an opportunity to talk about the illness with a mental health professional involved in the parent's treatment. Only one-quarter (ten offspring, or 24 percent) reported that as a child he or she had been told by a doctor that the parent suffered from schizophrenia. Others were given no specific information about the illness or no information at all. Slightly more than one-third (14 offspring, or 36 percent) reported receiving counseling from a mental health professional to help them deal with the parent's illness.

It is of interest that one in four (ten offspring, or 26 percent) believed that their parent would recover. The majority seemed convinced that their parent suffered from a lifelong illness.

A substantial minority of the offspring played a caretaking role. Seventeen offspring, or 45 percent, indicated that they cared for their parent at some time. Nearly as many (15 offspring, or 39 percent) stated that their parent's inability to function demanded that they take over homemaking activities, a role shift requiring some to give up work or school activities (ten offspring, or 26 percent) or free time (12 offspring, or 32 percent). The impact of the parent's illness on the offspring's social role activities is shown in

Table 2.

Relationship with the nonpatient parent.

We asked offspring about their relationship with their nonpatient parent, who was primarily their father. Slightly more than half (21 offspring, or 54 percent) had ever lived with their father for any period of time throughout childhood and adolescence. Living arrangements involving the father tended to be unstable, as the fathers of one-third of the offspring (13 respondents, or 33 percent) had never married the offspring's mother, and nearly one-half of the fathers (of 19 offspring, or 49 percent) were divorced or separated from the mother during the offspring's childhood.

About one-quarter (ten offspring, or 26 percent) did not know the current whereabouts of their father, and seven (18 percent) believed that their father was no longer living. Although nearly one in four had no information about their father's health status, 14 offspring, or 36 percent, indicated that he had an alcohol problem; 12, or 31 percent, that he was violent or abusive at home; 12, or 31 percent, that he had a serious health problem; seven, or 18 percent, that he had a mental or emotional problem; six, or 15 percent, that he had a drug problem; six, or 15 percent, that he had been in jail or prison; and four, or 10 percent, that he had been treated in a psychiatric hospital. Slightly more than one of four offspring with at least occasional contact with their father stated that they got along well or moderately well.

The most significant nurturing adult.

Only two offspring, or 5 percent, indicated that their nonpatient parent was the most significant nurturing adult during childhood and adolescence. Eleven offspring, or 28 percent, revealed that the parent with mental illness played this role in their lives.

However, biological parents were not as important for most offspring as were other relatives. Fifteen offspring, or 39 percent, told us that a grandparent was the most significant nurturing adult, and eight, or 21 percent, indicated that this person was an aunt or an uncle. Only one offspring reported that a foster parent played this role. Nearly three-quarters of the offspring (28 respondents, or 72 percent) stated that they currently got along well or moderately well with the most significant adult, and that this person gave them material support, including food, clothing, and shelter, as well as emotional support and companionship.

Current adjustment of offspring.

Most offspring were living in city apartments shared with family members. More than one-third (15 respondents, or 39 percent) were currently residing with the parent with mental illness. Although none of the offspring was currently homeless, nearly one-fifth (seven respondents, or 18 percent) reported an earlier episode of homelessness with an average duration of three to four months. Nearly half of those respondents experienced the episode of homelessness in the company of the parent with mental illness.

The majority of offspring (34 respondents, or 87 percent) had at least one close friend with whom to share life's ups and downs. Typically, the relationship was close enough to involve free and open discussions of important issues, including the nature and impact of the parent's illness. Few avoided discussing the parent's illness with a close friend because of embarrassment or fear of being misunderstood.

Eleven offspring, or 28 percent, were currently living with a partner who was gainfully employed and able to contribute to the household income. Eight offspring, or 21 percent, reported that they had experienced violence in their relationships with partners. Many offspring (23 respondents, or 59 percent) had children, and most were raising their children alone.

One in three offspring (13 respondents, or 33 percent) reported a current health problem that was usually not serious. The respondents varied considerably in overall mental health status. Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scores, which measure the extent to which any psychiatric symptom interferes with the ability to function in usual social roles, ranged from 38 to 90. The median score was 74, indicating that symptoms, if present, are transient and cause only slight impairment in social, occupational, or school functioning.

Depression was the most common symptom and syndrome. Fourteen offspring, or 36 percent, reported at least one episode in their lives when they felt depressed, sad, or blue most of the time every day for at least two weeks. For seven offspring, or 18 percent, the depression was severe enough to qualify them for a diagnosis of major depression (see

Table 3). The prevalence of affective disorder among these offspring was nearly twice the lifetime prevalence in the general population (

23).

Posttraumatic stress disorder was experienced by five offspring, or 13 percent. Four subjects, or 10 percent, received a lifetime diagnosis of alcohol abuse or dependence, and five, or 13 percent, had a diagnosis of drug abuse. Thus the prevalence of drug abuse among these offspring was about double the lifetime prevalence in the general population (

24). Only two offspring, or 5 percent, received a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder. It is of interest that one offspring received a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, and none received a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Three offspring, or 8 percent, had concurrent major depression or schizoaffective disorder and substance abuse.

Mental health treatment.

More than one-third of the offspring (15 respondents, or 39 percent) had received outpatient psychiatric treatment. Two offspring, or 5 percent, had received treatment in a psychiatric hospital, and four, or 10 percent, received some type of psychiatric medication.

Of the ten offspring with psychiatric diagnoses of major depression, schizoaffective disorder, or drug and alcohol abuse, six, or 60 percent, received some form of treatment, and four, or 40 percent, remained untreated. All untreated offspring had a diagnosis of major depression, and one also had concurrent substance abuse.