Patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder are at much higher risk of committing suicide than the general population. In the U.S., local and regional epidemiological findings on risk of suicide vary from a roughly sixfold increase (

1) to a 36-fold increase (

2) in risk among patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. A Swedish study found that suicide was 12.3 times more common among patients with schizophrenia than in the general population (

3). In Canada a 19.6-fold increase in risk has been reported (

4). Several studies have indicated that at least 10 to 15 percent of patients with schizophrenia eventually die by their own hand (

5,

6). These figures suggest that the suicide risk among patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder approaches, or is comparable to, that observed among patients with severe depression.

Besides comorbid major depression, there are a number of possible reasons for increased suicide risk among patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. In their more lucid moments such patients may realize that drastic changes are occurring in their minds and lives. They may grasp that they have a lifelong, disabling illness that is devastating their health, severely limiting their personal relationships and career opportunities, and causing social stigmatization and isolation. Given the harsh realities of uncontrolled severe schizophrenia and its consequences, suicide may be seen by some as a rational Socratic act.

Even in the absence of depressed mood, the patient's delusions, hallucinations, or misperceptions may make death an attractive alternative. Also, some patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder are prone to substance abuse, and the risk of potentially lethal consequences due to overdose or unsafe behavior while intoxicated may be increased for these patients because of the attendant psychosis. Finally, self-destructive thoughts and behaviors are likely to be less predictable and potentially more lethal among patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder than among persons without those disorders.

Medication-related factors may also increase the suicide risk. Inadequate clinical efficacy of the prescribed antipsychotic drug, which leads to poorly controlled symptoms, heightened social and personal problems, and an unstable, often chaotic disease course, is a major source of risk. Motor disorders such as tardive dyskinesia, which is often irreversible, are associated with many antipsychotic drugs. Such side effects and adverse effects add to the patient's disability and hopelessness and exacerbate disease-related suicide risk.

Compared with conventional neuroleptics, clozapine decreases psychotic and behavioral symptoms and decreases the need for hospitalization among patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder (

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12). In an experimental context, Meltzer and Okayli (

9) found an 86 percent reduction in suicide, attempted suicide, and suicidal ideation among a group of patients with schizophrenia treated with clozapine, compared with control subjects who did not receive clozapine. Both groups were composed of patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Results were obtained using a retrospective count of serious suicide attempts (based on a 0-to-5 scale of "probability of success"). In an epidemiological study covering the years 1990 through 1993, Walker and associates (

13) found that among all U.S. patients under age 55 who had been treated with clozapine and for whom cause of death could be verified from death certificates, current users of clozapine had an 82 percent reduction in suicide risk compared with past users. However, we have been unable to identify in the psychiatric literature any studies relating specifically to the effect of clozapine on suicide risk in a clinical practice setting.

The Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Rehabilitation cares for approximately 80,000 patients with severe and chronic mental illness, of whom approximately 30,000 have a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. At any one time, more than 95 percent of these patients are treated as outpatients in state-funded community settings.

Clozapine was first prescribed in the Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Rehabilitation system (outside of humanitarian protocols) in 1991. An early, largely financial cap on clozapine use kept the number of recipients relatively low compared with the number receiving traditional antipsychotic medications, a condition that continues at this writing for clozapine and other atypical neuroleptics. The number of patients who received the drug was 294 in 1991, increasing steadily to 3,053 in 1996. The average annual number of patients receiving clozapine from 1991 to 1996 was 1,310. The total number of patients who had taken clozapine for more than 90 days during those six years was about 3,800, given a dropout rate of only 20 to 25 percent.

Clinical and demographic data for all patients within the Texas public mental health system are recorded in an agency database. Patients' deaths, including all verified or suspected suicides, are reported to the mental health system's central office. Follow-up by the system's office of medical services determines the cause and manner of death in almost all cases of suicide or suspected suicide. Particularly good suicide reporting data are available for the two-year period between 1993 and 1995, and these data form the basis for our core analysis of suicide risk among all patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder.

Detailed data on deaths of all patients currently or formerly treated with clozapine are also reported promptly to a second database maintained by the mental health system. The study period for patients who received clozapine in the Texas public mental health system can therefore be extended back to 1991.

Suicide risk can be expressed as a standardized mortality ratio, in which observed mortality (in this case suicide) in the population of interest is compared with expected mortality in a reference population. Suicide risk may also be expressed as a simple rate; for example, the actual number of suicides per 100,000 persons per year in the population of interest is compared with the actual number per 100,000 persons per year in other populations. This study compares the simple rate of suicide in several populations: all severely and chronically mentally ill patients in the Texas state mental health system, patients in this system with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, and the subset of patients with such disorders who were treated with clozapine. The study findings are discussed in relation to the suicide rates reported for other cohorts of patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, as well as for the general U.S. population.

Editor's Note: Experiences with the use of clozapine in treatment of patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder and describe by several contributors to this month's issue. William H. Reid, M.D., M.P.H., and his colleagues report evidence of reduced suicide rates among patients treated with clozapine (page 1029). Daniel J. Luchins, M.D., and his associates analyze cost of treatment for patients who begin taking clozapine in an outpatient setting (page 1034). The treatment of a patient who became pregnant while taking clozapine is described by Ruth A. Dickson, M.D., F.R.C.P.C., (page 1081). Pregnancy and clozapine is the subject of the Taking Issue Column by Glenn W. Currier, M.D., M.P.H., and George M. Simpson, M.D., and the others discuss the case of a man who developed agranulocytosis during a second trial of clozapine despite a succesful previous trial (page 1094).

Methods

The records of all deaths of patients treated with clozapine in the Texas mental health system between 1991 and 1996 were reviewed to identify cases of suicide. Patients were considered to have been clozapine recipients if, at the time of death, they had been receiving clozapine for at least 30 days and had not discontinued the drug for more than 14 days. Patients for whom clozapine had been prescribed but for whom no information about the duration of treatment or drug discontinuation was available were also considered to have been clozapine recipients. For the purposes of the study, suicides included both verified suicides and deaths in which suicide was considered reasonably likely, regardless of whether it was initially suspected.

For the total patient population in the Texas system and the population of all patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, all cases of suicide during the 24-month period for which the most complete agency data were available, May 1993 to May 1995, were included in the analysis. In addition, all fatalities reported in the Texas mental health system's database were manually reviewed by the director of medical services or the first author to determine whether any additional patients should be included in the suicide group. Both reviewers were at the time blind to whether clozapine had been prescribed for a given patient. No unrecorded suicides or likely suicides were uncovered in the manual review. The complete list maintained by the Texas mental health system, which also contained diagnostic and demographic information, was once again compared with the agency's database of patients who had received clozapine to determine whether any deceased patient had received clozapine during the period immediately before death but had inadvertently been omitted from the clozapine database.

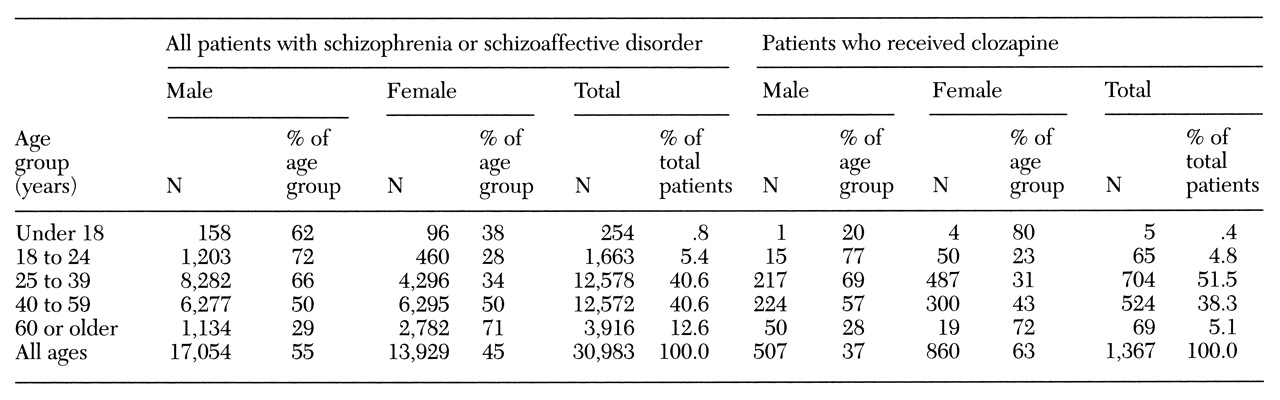

Annual rates of suicide per 100,000 patients were calculated for three groups of patients within the Texas public mental health system: all psychiatric patients, all patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, and the subset of patients with such disorders who were treated with clozapine. Data on gender and age for the last two groups during a representative year are reported in

Table 1.

Results

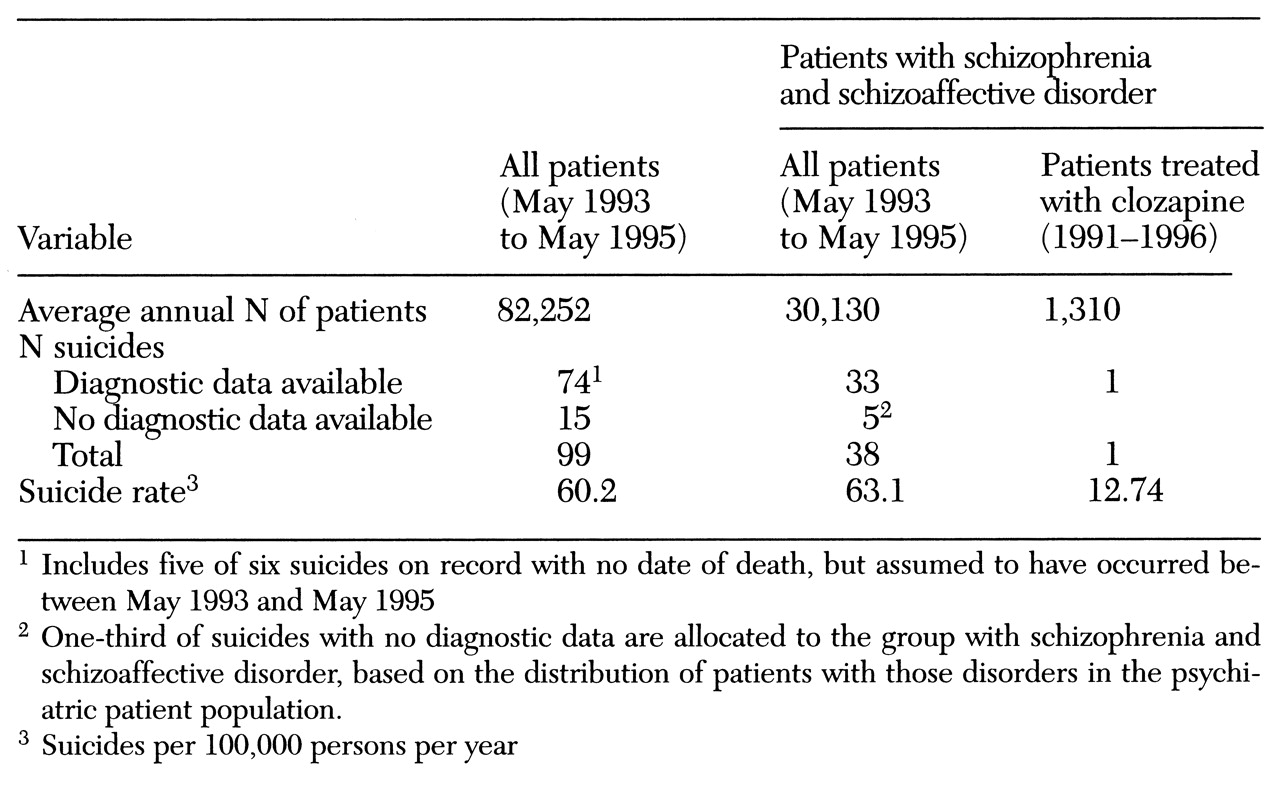

Among an annual average of 30,130 patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder in the Texas public mental health system, 38 committed suicide during the two-year period for which detailed records were kept (May 1993 to May 1995). This number represents an annual suicide rate for all patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder of 63.1 per 100,000 patients. During this period, the total number of suicides among all psychiatric patients (an average annual census of 82,252, including those with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder) within the Texas system was 99, for an annual suicide rate of 60.2 per 100,000 patients.

Among the patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder treated with clozapine, only one suicide occurred between 1991 and 1996. Given an average of 1,310 patients continuously receiving the drug each year, the annual suicide rate for clozapine-treated patients was 12.74 per 100,000, substantially lower than the rates among all psychiatric patients in the Texas system and among patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder in that system. These results are summarized in

Table 2.

The subgroup of patients who received clozapine contained a higher proportion of female patients than did the group of all patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder —63 percent versus 45 percent (see

Table 1). However, the practical impact of this difference was likely to be minor, given the general finding that suicide rates of female patients with schizophrenia are approximately equal. The age distribution of the clozapine-treated subgroup was similar to that of the overall population of patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, with no large numerical imbalances that could skew the analysis significantly.

Discussion

The data from the Texas public mental health system indicate an annual suicide rate among patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, as well as among all psychiatric patients, that is approximately five times higher than that of the U.S. population in general: 63.1 and 60.2 per 100,000 persons, respectively, versus 12 per 100,000 persons in the U.S. This excess suicide rate among severely mentally ill patients is consistent with, although perhaps somewhat less pronounced than, the excess suicide rates reported in other studies of populations of patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder (

1,

3,

4,

6,

14).

The Texas data suggest a much lower annual suicide rate of 12.74 per 100,000 for the subgroup of patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder who were treated with clozapine. This figure is similar to the suicide rate estimated from the Sandoz/Novartis Serious Adverse Events (SAVES) U.S. database—15.7 per 100,000. Although the data reported here do not prove a direct causal relationship, the findings are nevertheless consistent with the hypothesis that clozapine therapy markedly reduces suicide risk among patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder.

It is informative to compare the suicide data of the Texas subgroup of clozapine-treated patients with data from the Sandoz/Novartis SAVES database. The SAVES database includes data on unofficial suicides recorded among all persons who have received clozapine since 1990. (The SAVES database is not an official registry of suicides, and data on suicides are provided voluntarily by clinicians. All data are confidential, represent the clinicians' opinions, and are not verified with official death certificates.)

The Sandoz/Novartis database suggests that an average of 63,876 U.S. patients received clozapine each year between 1990 and 1996. Using the same criteria for identifying suicides that we applied to the data from the Texas mental health system, a total of 70 suicides of clozapine-treated patients in the U.S. were reported to the Sandoz/Novartis database up to June 1996, for an annual suicide rate of 15.7 per 100,000.

As in all populations of outpatients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, unknown proportions of patients in the study groups failed to take their medications as prescribed. Patients treated with clozapine were likely to be more compliant with their medication regimen than patients on other medications because they were seen every week for white blood cell monitoring, and long-term noncompliance with the monitoring protocol constitutes de facto withdrawal from clozapine therapy. The fact that clozapine recipients were seen more frequently might also have contributed to their reduced suicide rate. Although patients who received clozapine rarely saw a psychiatrist on their routine visits for hematological monitoring, they did have weekly contact with laboratory and pharmacy personnel and were aware that their progress was being closely followed. It is possible that through this process, patients at high risk of suicide were identified and appropriate measures were taken, or that human contact per se favorably influenced the suicide risk. Many severely ill patients who did not receive clozapine were also followed closely, through aggressive case management and assertive community treatment, but others were seen only every few weeks or months.

Although the study groups were similar in many respects, this study did not differentiate specific medication-related improvements from any possible additional patient response due to clinic visits, case management, and other aspects of care. Because clozapine therapy cannot be prescribed without routine blood monitoring, it is perhaps academic to discuss purported disaggregated effects of weekly venipuncture versus direct drug effects; they constitute a system. Nevertheless, in our opinion it is unlikely that weekly venipuncture and pharmacy visits by themselves account for the large reduction in suicide risk that appears to accompany clozapine therapy. Research on the impact of such weekly interactions among patients receiving conventional medication would be informative.

The annual suicide rate we extrapolated from the single case of suicide recorded among patients treated with clozapine over the six-year period is adjusted for the annual average number of patients taking clozapine, which varied from 294 in the first year to 3,053 during 1996. One cannot know whether the single suicide in six years was a representative event, and so the estimated suicide rate among clozapine-treated patients may be inaccurate. As for any rare-event phenomenon observed in a relatively small number of patients, a few additional events would make an appreciable difference. For example, the 95 percent confidence interval (CI) (Poisson distribution) of a single event ranges from 0 to 6, yielding a 95 percent CI of 0 to 52.5 for an observed suicide rate of 12.74 per 100,000 per year among patients treated with clozapine. Nevertheless, the estimated suicide rate among clozapine-treated patients in this cohort approximates that calculated from the Sandoz/Novartis SAVES database for all U.S. clozapine-treated patients.

The one clozapine-treated patient who committed suicide received her last dose four days before her death. Two patients who had previously been treated with clozapine but who did not qualify for inclusion in the clozapine group committed suicide during the six-year study period. Neither had taken clozapine in the recent past: one had been withdrawn from clozapine many months before the suicide for lack of compliance with the medication regimen and the monitoring protocol; the other had been withdrawn for unknown reasons 23 months before his death.

The distribution of causes of death among the suicides by patients served by the Texas public mental health system showed that firearms and overdose or poison collectively accounted for 74 to 75 percent of the suicides among both males and females. However, the most prevalent cause differed by gender. Almost half of suicides by male patients (46 percent) were by firearm, and 26 percent were by overdose or poison. Among female patients who committed suicide, 46 percent took an overdose or poison, and 30 percent used firearms. A smaller number of the remaining suicides were by hanging (18 percent of male patients and 9 percent of female patients) or by gas or carbon monoxide poisoning (5 percent of male patients and 6 percent of female patients).

In accordance with the prescribing policy of the Texas department of mental health, the clozapine recipients were among the most severely ill patients served by the agency and were arguably at higher risk of suicide than the remainder of patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. On the other hand, the clinical and demographic characteristics of the clozapine-treated patients were similar to those of the overall group of patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Many patients with those disorders were, in fact, eligible for clozapine therapy but were unable to receive the drug due to financial constraints.

The suicide rate among patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder in the Texas public mental health system was somewhat lower than that reported in other long-term cohort studies. It is possible that our review may have missed some suicides among young patients with recent onset of a disorder. For example, Mortensen and Juel (

15) have suggested that the suicide risk in young patients with a recent onset of the disorder may be 150 to 300 times greater than that in the general population but that these early suicides are lost to study because the patients had not received a diagnosis before death.

Another reason for the lower suicide rate for the Texas patients might be that the majority of severely ill patients in the Texas system received better care and monitoring and were more geographically stable than patients in other cohorts. It is also possible, although in our view unlikely, that the reporting system of the Texas department of mental health missed a large number of suicides or that our method of adjudicating suicide as the cause of death was more conservative than that used by other investigators.

Finally, it is possible, but extremely unlikely, that many high-risk patients in Texas were not served by the public mental health system or that they left the system before committing suicide. Regardless of the relationship of the Texas data with published findings on suicide among other cohorts of patients with schizophrenia, the comparison reported in this paper is between two very similar groups of patients treated in the same public mental health system—all patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder and the subgroup of those patients on clozapine therapy.

Conclusions

This review of suicides among patients with diagnoses of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder in a large state mental health system and the subgroup of patients who received clozapine suggests that clozapine therapy was associated with a lower suicide rate than were conventional antipsychotic therapies. This association of reduced suicide risk with clozapine therapy is consistent with previous reports from clinical and epidemiological studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ann Valdez, M.T., C.L.S., and Susan Stone, J.D., M.D., of the Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation for their assistance, and Anthony Bianchini, Carmine Cupo, and Vikram Dev, M.D., of Novartis for the provision of relevant clozapine data. Analysis and manuscript preparation were supported by a grant from Novartis Pharmaceuticals AG.