The Program for Assertive Community Treatment (PACT) integrates vocational and mental health services to facilitate community employment of persons with severe mental illness (

1,

2). However, most assertive community treatment programs have not emphasized vocational rehabilitation as a program responsibility (

3,

4).

Employment offers unique contributions to the successful community stabilization of persons with severe and persistent mental illness by countering patients' impoverishment and social isolation (

5,

6). We sought to determine if the shorter-term employment gains reported in studies of the PACT model (

1,

2,

5) could be sustained over a decade of PACT modeled services.

Program description and rationale

The PACT-modeled program was established in rural Illinois in 1984 with funding from state mental health and vocational rehabilitation agencies. The aim was to treat state hospital patients who had been deemed unmanageable as outpatients by local community mental health centers; the program also had a goal of training mental health professionals in the PACT model (

1,

2). The only deviation from the PACT model included in the program's design was that it accepted referrals from the state hospital for short-term care of persons from other counties who returned to their community of origin after they were stabilized.

All staff—seven full-time nurses, social workers, and psychologists and a part-time psychiatrist—had faculty appointments and were responsible for training university medical students, psychiatric residents, and other professional trainees to function as PACT team members. Team members shared responsibility for a caseload of 70 clients. The program operated seven days per week: 12 hours a day on weekdays and eight hours on weekends. Staff were on call after hours.

The team met daily to review the status of each client and to plan the day ahead. It also met weekly to prepare and review treatment plans. Daily assignments of case managers to provide client services were coordinated by the team leader and assistant team leader, both of whom were master's-level social workers. Case managers recorded the status of clients in their assigned caseloads each day using an automated data system.

Persons who were referred to the PACT program were told that it was a vocational program. Although clients were not required to work to remain in the program, the theme of increasing and maintaining work motivation pervaded the interaction between staff and clients. The routine of dealing with work—an area of experience common to staff and clients (

6)—provided a primary context for developing social and instrumental skills. Team members assisted clients in identifying interests, gaining relevant skills, applying for competitive employment, and obtaining interviews. Employment opportunities within the agency introduced clients to work habits, helped clients develop consistency in attendance and performance and explore their interests, and helped in building rapport between clients and staff.

If clients were willing to disclose their disability to potential employers, staff often worked directly with employers to advocate and negotiate needed accommodations. Otherwise staff showed clients how to use resources such as want ads and employment agencies to identify work opportunities and held mock interviews. Staff intervened on and off the job to strengthen clients' work habits and skills. Staff also worked with community businesses to develop blocks of jobs for clients within individual businesses and provided on-site employment support for clients when needed. Staff assured prospective employers that the required work would be performed and when necessary staff worked alongside clients until needed performance levels were achieved.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective evaluation after ten years of program operation, using several types of information. One source of information was clients' discharge summaries for all psychiatric hospitalizations for the five years before program enrollment and for the period during enrollment. Clients gave informed consent for dates of hospitalization to be verified at all public and private hospitals in the area. A second information source was case managers' weekly home visit reports, which allowed tracking of clients' residential arrangements.

A third source was daily records of all client-staff contacts. The records were maintained in an automated reporting system, and they included the location of the contact, such as office, home, or community, and the category of the contact, such as crisis intervention, psychiatric management, psychotherapy, psychiatric rehabilitation, or case management. The fourth type of information, also derived from the automated reporting systems, was the dates and weekly hours of employment. Clients' histories of preprogram residential and employment experience were obtained in separate interviews with clients and families. Major discrepancies between reports were pursued until resolved.

Results

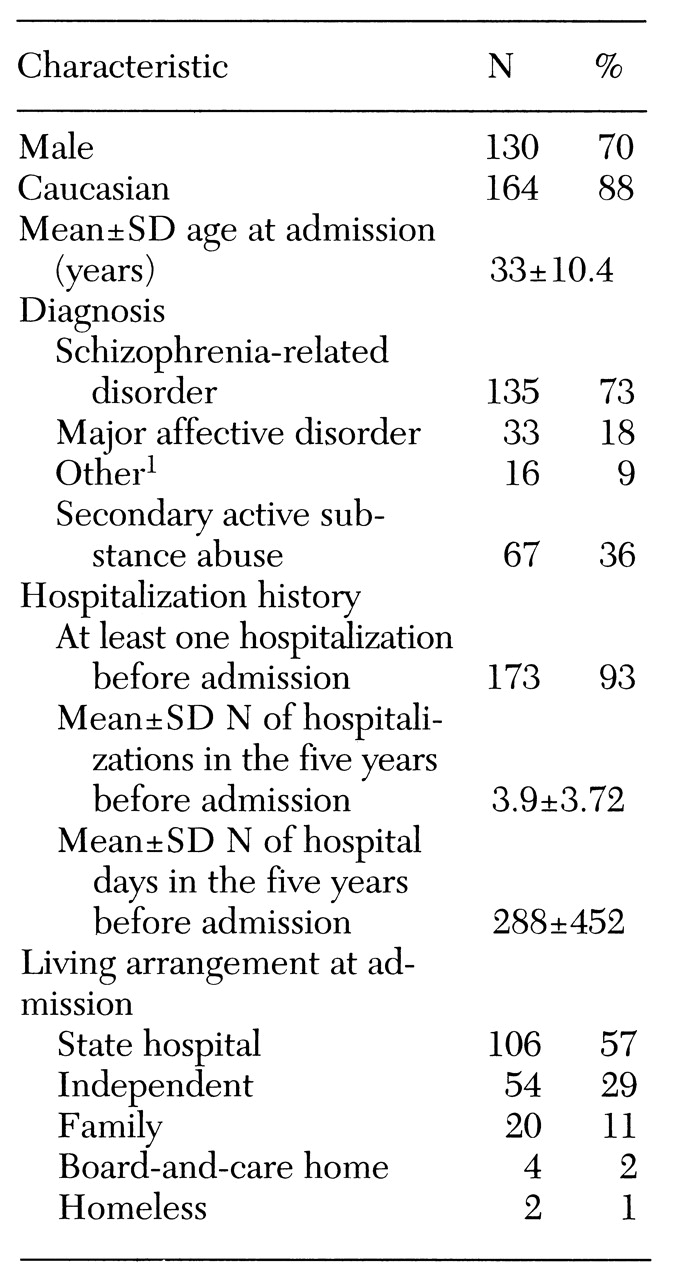

A total of 184 clients were served from December 1984 through February 1994. Characteristics of the clients at the time of admission are shown in

Table 1. The typical client was male, younger than age 40, had multiple hospitalizations, suffered from schizophrenia or major affective disorder, had a history of substance abuse, did not live independently, was unemployed, and had been refused outpatient service by other agencies because of uncooperativeness.

The 184 clients could be divided into three almost equal groups in length of stay in the program. Thirty-three percent left the program within a year of enrollment, 34 percent were in the program for one to four years, and 33 percent for longer than four years. The median length of enrollment of the 70 active clients at the end of the study period was 73 months, with a range from 2.6 to 123.7 months.

Eighty-three percent of contacts with clients occurred in out-of-office locations in community-based settings. The main purpose for 74 percent of contacts was rehabilitative, including providing support with coping and problem solving, assistance with activities of daily living, and vocational support. Fourteen percent of contacts were related to case management, including coordinating services with other agencies, accompanying clients to appointments, and delivering medication. Ten percent were office-based therapy sessions, and 1 percent were to provide crisis intervention during after-hours emergencies.

The percentage of clients living independently increased from 29 percent at program entry to 90 percent while in the program. Most clients in the program lived alone in their own apartments. A total of 92.9 percent of clients had been previously hospitalized, and most clients, or 57.6 percent, were admitted to the program directly from the state psychiatric hospital. Some clients were accepted from a local emergency room after community mental health centers refused to provide the client with outpatient care.

More than half of the clients, or 56.5 percent, were not hospitalized while in the program. The 81 clients who were hospitalized had a median of two admissions and 35 inpatient days while enrolled in the program (mean±SD=3.22±3.86 admissions and 110.7±195.62 inpatient days, with a range from three to 1,137 days). Days of hospitalization were skewed by data for 13 clients who spent at least six months hospitalized (range=221 to 1,137 days) while enrolled in the program. These clients accounted for 66 percent of the total hospital days and spent an average of 455 days hospitalized, or 18 percent of their time in the program. When data for these 13 clients were omitted, the mean number of annual admissions for the remaining 172 clients was .69±3.85, and the mean number of days hospitalized per year was 8.35±23.33 days.

None of the clients were employed at the time of program entry. Seventy-nine of the 124 clients enrolled in the program for a year or longer (63.7 percent) were employed at some time during their enrollment, compared with seven of 61 clients (11.5 percent) who were enrolled for less than one year. Over the ten-year period, the average rate of employment was 33 percent. Of the 86 clients who attained employment, 17 clients, or 19.8 percent, were employed less than 25 percent of the time they were in the program, 22 clients, or 25.5 percent, were employed 25 to 50 percent of the time, and 47 clients, or 54.7 percent, were employed more than 50 percent of the time. While employed, 7 percent of the clients averaged less than ten hours of work a week, 76 percent averaged ten to 20 hours a week, and 17 percent averaged more than 20 hours a week.

Discussion and conclusions

The study results compare favorably with the employment rates of 5 to 21 percent reported for persons with severe and persistent mental illness generally (

7) and with the rates reported for other assertive community treatment approaches that systematically integrate state-of-the-art community mental health and supported employment interventions (

8,

9,

10). The original PACT program has maintained annual employment results similar to or exceeding those we report (Knoedler W, personal communication, 1996). For example, in 1996 a total of 60.8 percent of clients in the original PACT program were employed at any time during the year. Employed clients spent 63.9 percent of the year employed from five hours a week to full time. In a review of 17 research studies, Bond and associates (

10) found that 58 percent of clients in supportive employment programs obtained competitive employment, compared with 21 percent of clients in programs offering traditional services.

Some clients who left within a year of admission voiced eagerness to return to their homes and their intention to avoid full participation in our program, which they viewed as becoming rooted away from home. Other clients were resistant to referral, and some began to disengage from the program soon after admission. Although the program provided outreach to these clients over several months, the team reported being unable to establish a working alliance centered on active treatment and employment with many of these clients. These considerations may offer a partial explanation of the low employment rate of clients involved with the program for less than a year.

We ascribe our long-term successes in supporting clients in employment to our consistent emphasis on five aspects of the program. First, the agency leadership and service team remained committed to employment intervention as a core service. Second, rather than brokering employment services through other agencies, we designed and maintained these services within the PACT model program, a strategy recently supported by Bond and associates (

10).

Third, we took both symbolic and concrete steps to create a culture within the program that motivates clients to takes risks in employment initiatives. Fourth, we assigned specific staff members to lead the development of employment opportunities and made all members of the team accountable for individual clients' attaining employment. Fifth, we trained clients on the job in the course of work, not in anticipation of work (

1,

10).

We view our results as embodying these factors but as still limited by a lack of resources for assessment and training and lack of opportunities for transitional and competitive employment for clients (

5,

6). In addition, the results are affected by the lack of commitment of the mental health system, which tends to respond reactively to clients' symptoms rather than preventively to clients' social and vocational needs.