The mental health system and the police have a long history of interaction (

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6). Thirty years ago Bittner (

2) noted that managing persons with mental disorders has long been considered a part of police work. More recently, a study examining crisis response services in 69 U.S. communities noted that law enforcement officers play a critical role in mobile crisis services, particularly in providing assistance in potentially dangerous situations (

7). Despite these findings, a survey of California law enforcement agencies suggested that most law enforcement officers are given insufficient training in identifying, managing, and referring mentally ill persons (

8).

In a survey of mobile crisis services, Geller and colleagues (

9) reported that mobile mental health crisis teams appear to be widely accepted as an effective approach to emergency service delivery. However, they noted that this perception is based on little or no empirical evidence.

To facilitate further research into this issue, it seems necessary to first organize the various types of interactions between police and mental health professionals into well-defined categories; to do so was the purpose of this study.

Methods

A survey of urban police departments in the 194 U.S. cities with populations of 100,000 or more was conducted in 1996. Completed surveys were received from 174 departments (90 percent) in 42 states. Besides background information on the police department and locale, the survey requested information about interactions between police and mental health professionals—specifically whether the police department had any policies or procedures designed to divert into treatment or provide crisis assistance to persons thought to be mentally ill who might otherwise be arrested. Also requested was information about the availability to all line officers of departmental training in managing mentally ill persons and whether the department employed specially trained mental health officers or deputies.

Departments were asked to rate on a 5-point Likert scale the perceived overall effectiveness of the department to respond to a person with a mental illness who is in crisis. This perceived effectiveness scale was used as a "first-cut" and cost-effectiveness measure to identify exceptional programs. Steadman and colleagues (

10) reported that program ratings of perceived effectiveness correlate highly with program characteristics and objective measures of program success.

To identify existing response strategies, we asked departments three questions: "does your department have special mental health officers or deputies who are employees of your department?" "does your department provide on-site emergency psychiatric evaluation of mentally ill persons?" and "does your department have other collaborations with emergency mental health services? If yes, specify." The open-ended question provided more specific accounts of the departments' crisis response. We then examined the responses for similarities across departments and combined the similar strategies into categories. This procedure yielded three primary police-mental health professional response strategies.

Results

Typology of crisis response

Among the 174 police departments in our study, 7 percent of all police contacts, both investigations and complaints, involved persons believed to be mentally ill. More than half of the departments (96 departments, or 55 percent) indicated that they had no specialized response for handling these types of incidents.

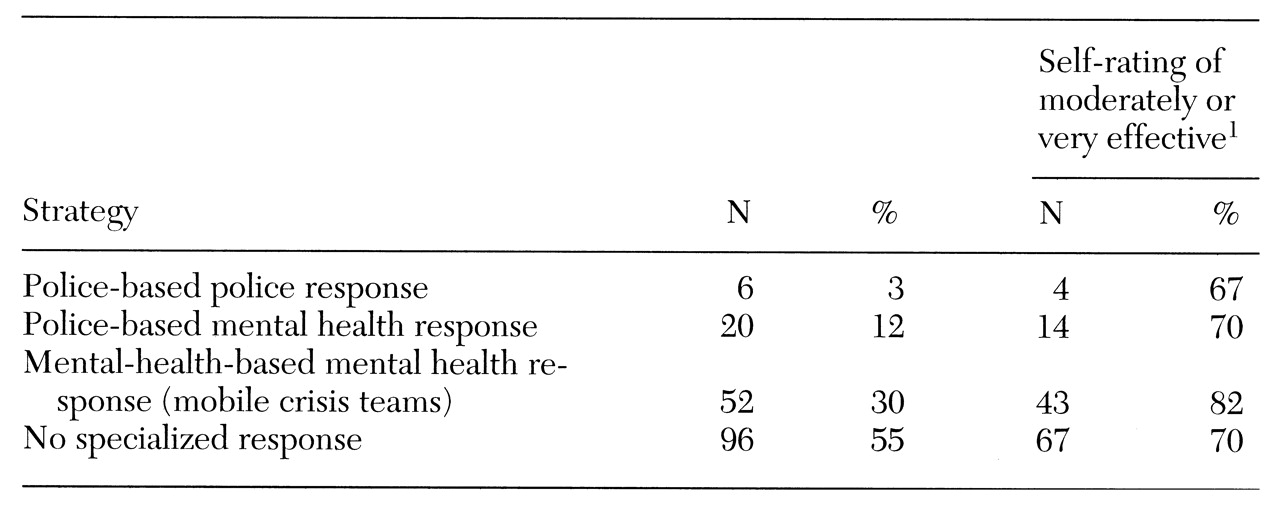

Table 1 shows the three basic strategies that were used by the 78 departments that had a specialized response. These strategies appear to differ substantially in their organization, policies, and procedures. The extent to which they actually differ in practice will require on-site observation, which will be the next phase of this study.

Police-based specialized police response

This strategy was used by six of the 174 departments (3 percent). It involves sworn officers who have special mental health training to provide crisis intervention services and to act as liaisons to the formal mental health system. Some of these programs used additional services as a secondary response.

Police-based specialized mental health response

This strategy was used by 20 of the departments (12 percent). Mental health consultants are hired by the police department. The consultants are not sworn officers, but they provide on-site and telephone consultations to officers in the field. Eight departments used teams of social workers, and 12 had mental health professionals, such as a psychologist, on staff.

Mental-health-based specialized mental health response

This strategy was used by 52 departments (30 percent). If a program used any other type of response, it was not placed in this category, which includes only programs that rely solely on mobile crisis teams. The teams are part of the local community mental health service system and have developed a special relationship with the police department to respond to special needs at the site of an incident.

Perceived effectiveness by model type

Table 1 also shows the percentage of the 174 programs that rated themselves as moderately or very effective. At least two-thirds of all departments, even those with no specialized response program, rated themselves as moderately or very effective in dealing with mentally ill persons in crisis. No significant relationships were found between the models in perceived effectiveness.

Despite the lack of any significant pattern between the models and perceived effectiveness, 43 of the 52 programs with mobile crisis teams (82 percent) indicated that their overall ability to respond to people with mental illness in crisis was moderately to very effective. This rating was higher than the average perceived effectiveness of other models, including that of no specialized response, but the difference was not significant.

Ten of the 20 programs that had a police-based mental health response (50 percent) rated themselves as very effective, compared with only 20 to 35 percent of the other model types, including that of no specialized response.

Another important strategy, often used in conjunction with a specialized response program, appears to be the use of a crisis "drop-off center" where police officers can literally transfer mentally ill persons in crisis to mental health staff, thus reducing the officers' down time. Indeed, police departments that used a drop-off center were significantly more likely than other departments to perceive themselves as highly effective (χ2=21.69, df=1, p<.001). Crisis drop-off centers were used by 118 (68 percent) of the 174 departments surveyed.

Discussion and conclusions

A majority of police departments in U.S. cities with populations of 100,000 or more do not have a specialized strategy to respond to persons in crisis who may have a mental illness. Among those that do, three primary approaches can be identified: a police-based specialized police response, a police-based specialized mental health response, and a mental-health-based specialized mental health response.

A very small percentage of departments (3 percent) indicated that they had a specialized unit of officers who were trained to handle crisis calls involving mentally ill persons. This innovative strategy appears to be a relatively new type of police response developed under community policing initiatives. The use of a police-based unit of mental health professionals also appears to be an innovative response; such units range from a team of specially trained social workers to staff psychologists who do consultations with officers in the field. The most widely used method of response is a mobile crisis team, based in the mental health system, that provides assistance on the scene.

One note of caution is that the survey reflected only urban police departments, and it is possible that the typology would be quite different if specialized mental health responses in rural areas were taken into account.

This classification of three types of the various police-mental health collaborations can provide a framework for further research, preferably with an objective evaluation as opposed to a self-perceived rating of the effectiveness of these strategies.

Acknowledgments

This study was jointly supported by grant 96-IJ-CX-0082 from the National Institute of Justice and by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH)-Duke University Program on Services Research for People With Severe Mental Disorders. The authors thank Matthew Johnsen, Ph.D., for comments on the draft, as well as the program participants at the UNC-CH meeting on police-mental health crisis response who helped refine the typology: the Birmingham, Alabama, police department community service officer program; the police-mobile crisis teams of Albany, New York, Charleston, South Carolina, Knoxville, Tennessee, and Richmond, Virginia; and the Memphis, Tennessee, police department crisis intervention team.