Before new services are developed for families with a parent who has a psychotic disorder, several key questions need to be addressed. How many patients with psychotic disorders are parents? How much contact do those parents have with their children? What child care and family services have the parents used, and are there barriers to gaining access to existing services?

To help in service planning, this descriptive study aimed to identify the prevalence of parenthood in a representative sample of patients with psychotic disorders who were in contact with health services, and to assess the amount of contact between parents and their offspring. Child care use and barriers to gaining access to child care services were explored.

Results

A total of 342 individuals with a psychotic disorder participated in the study.

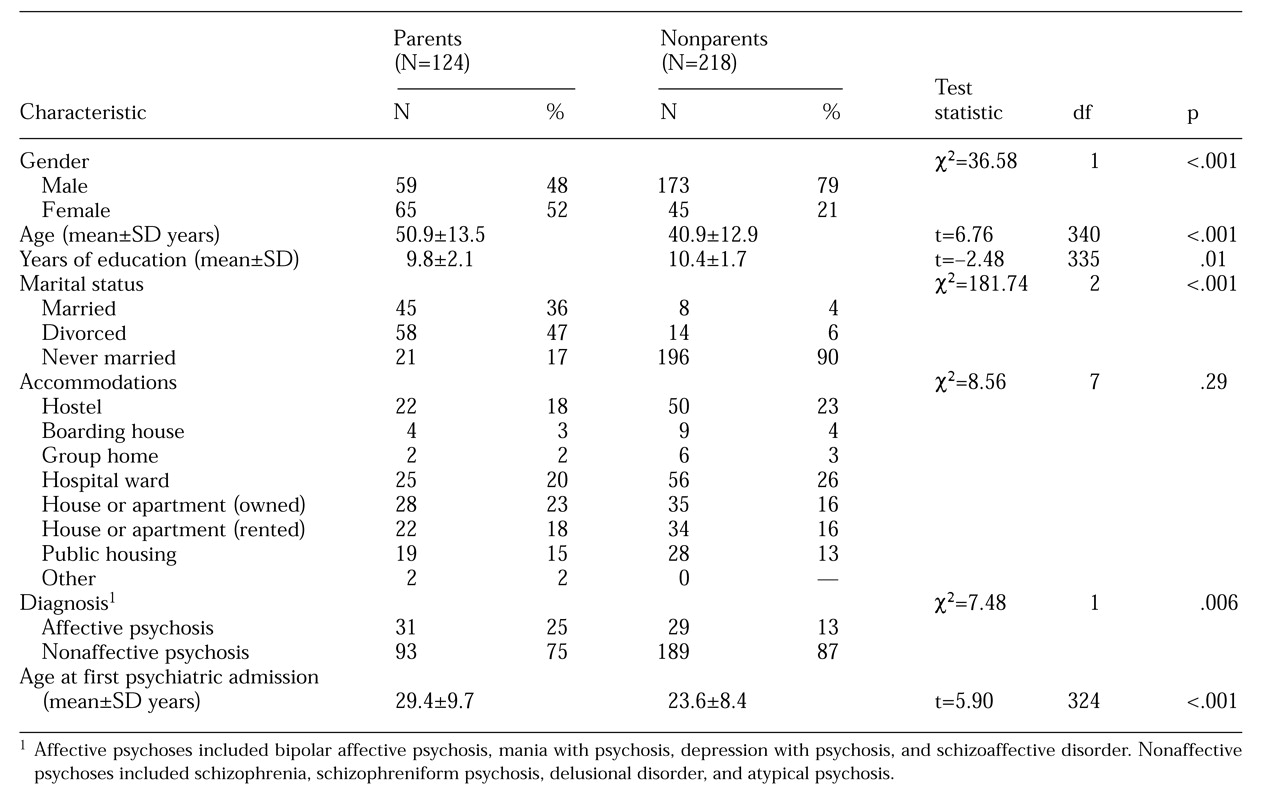

Table 1 presents information about participants and comparisons between parents and nonparents. A total of 257 patients—182 men and 75 women—met

DSM-III-R criteria for schizophrenia. Sixty patients—38 men and 22 women—had affective psychoses, which included bipolar affective psychosis, mania with psychosis, depression with psychosis, and schizoaffective disorder. The remaining 25 patients had either a delusional disorder or atypical psychosis.

Of the 342 participants, 124 (36 percent) were parents who had a total of 323 offspring. More than half of the women in the sample were mothers (65, or 59 percent). Only a quarter of the men were fathers (59, or 25 percent). Eleven of the parents (9 percent) had a partner with a serious mental illness.

Twenty-seven fathers and 21 mothers had children under age 16, and within this group, 20 parents (42 percent) had their children living with them. Among the 323 offspring, 75 (23 percent) were under age 16. Thirty-four of these children resided with the study participant, and 24 resided with the other parent. In many cases, the children resided with the well parent after the parents separated. Four children lived with relatives other than the patients' partners or former partners, and five children were in permanent foster care or had been adopted. The whereabouts of three children were unknown, and data were missing for five offspring.

For children under age 16 who were not residing with the study participant, data indicated that 11 children were seen by the participant at least weekly, 11 were seen at least several times a year, and 16 had not been seen for more than year. The 28 parents in this subgroup were asked about their overall level of satisfaction with the amount of contact with their offspring. More than half (17 participants, or 61 percent) described themselves as happy with the current level of contact, and ten participants (27 percent) said they preferred more contact. One participant preferred to have less contact.

Of the 248 offspring over age 16, 145 lived independent of the study participant, 22 lived with the study participant, 17 lived with the other parent, ten resided with relatives other than their parents, and six were in foster care or had been adopted. The whereabouts of 13 offspring were unknown, and data were missing for nine offspring. Twenty-six offspring had died.

A total of 111 of the 124 parents provided information about child care. Of these, most parents who responded to this question (N=97, or 87 percent) reported that they had relied on relatives for assistance. Twenty-seven parents (24 percent) relied on friends. Other forms of child care reported included foster care (15 parents, or 14 percent), day care (three parents, or 4 percent), family-based child care (three parents, or 4 percent), and emergency respite care (six parents, or 5 percent). Five children (5 percent) had been permanently adopted.

The child care assistance or interventions that parents reported using were organized by a variety of agencies, including the state government statutory child protection agency (19 parents, or 18 percent), mental health clinics (14 parents, or 13 percent), church groups (11 parents, or 10 percent), psychiatric hospitals (nine parents, or 8 percent), general community agencies (nine parents, or 8.3 percent), legal aid services (six parents, or 6 percent), maternity hospitals (six parents, or 6 percent), family courts (five parents, or 5 percent), and ethnic services (one parent, or 1 percent). Four parents (4 percent) endorsed the "other" category for the question about agency type.

Thirteen parents (11 percent of the parents who responded to this question) stated that a child care intervention had been made against their will.

Parents were also asked if certain prespecified factors had impeded access to ideal child care assistance. Of the 107 parents who responded to this question, the most frequently endorsed factor was the desire to manage alone (52 parents, or 49 percent). Other factors included not being able to pay for help (42 parents, or 40 percent), not thinking of seeking help (40 parents, or 37 percent), not knowing where to get help (38 parents, or 36 percent), fearing that children would be removed (32 parents, or 30 percent), being too embarrassed to ask for help (23 parents, or 22 percent), having no services available (22 parents, or 21 percent), and having asked for but not received help (13 parents, or 12 percent).

Discussion and conclusions

The survey of 342 individuals with a psychotic disorder found that more than a third (36 percent) were parents. The lack of participants from the private sector and the absence of a control group limit interpretation of the results. However, it is noteworthy that of the 48 parents in the study with children under age 16, only 20 had their children living with them. In addition, 13 of the parents in the study reported past child care interventions that had been carried out against their will, and nearly a third of the parents stated that they were reluctant to seek help with child care because they feared that their children would be removed from them.

The study provides insights into patterns of child care use among parents with a psychotic disorder. Clearly, such parents often rely on the support of family and friends. Providing timely and practical support to these individuals in the area of child care, as well as supporting the parents, may serve to keep such support networks intact. We agree with others who have commented on the important role that a supportive social support network can play in keeping children within the family system (

1,

4,

5).

This study found that many parents with psychoses acknowledged that they needed support but were unable to find it for various reasons. To improve outcomes for the current generation of parents with psychotic disorders, it is hoped that service planners can address barriers such as lack of affordable local services. Other factors found in the study that impeded access to optimal child care—such as embarrassment or fear of losing custody of children—require consumer education and practical demonstrations that services will respect the needs of parents with psychotic illnesses.

Currently in Australia, there is a lack of integration of the services required by families with a mentally ill parent. In many instances, the focus is on the adult and the mental health problem or on the children and their needs for care and protection. Service philosophies that focus on the functioning and maintenance of the family unit are vital to maintaining intact families and promoting positive outcomes for both parents and children (

4,

6,

7,

8,

9).