The purpose of this study was to examine predictors of treatment completion, a proxy for retention, in an outpatient program for opioid dependence. We studied all patients who entered treatment over a two-year period and examined the role of demographic variables and the therapeutic alliance in predicting treatment completion among patients receiving an effective pharmacotherapy in conjunction with an intensive behavioral therapy. We hypothesized that certain pretreatment variables, including fewer psychiatric symptoms, would be associated with treatment completion. We also hypothesized that patients with a stronger therapeutic alliance would be more likely to complete treatment, and that this therapist-patient relationship would be particularly important for treatment completion among patients with more psychiatric problems.

Methods

Patients

The patients were 114 individuals, each enrolled in one of five buprenorphine studies—three studies of dosing and two of detoxification—conducted over a two-year period (1994 to 1996) at the University of Vermont Substance Abuse Treatment Center. Criteria for entry into the studies included being over 18 years old and meeting DSM-III-R criteria for opioid dependence and the Food and Drug Administration's qualification criteria for methadone treatment.

Psychiatric and medical status was determined by history, physical examination, and laboratory evaluation. Evidence of active untreated psychosis or serious medical illness (for example, cardiovascular or liver disease) and pregnancy were exclusion criteria. Codependence on other drugs did not exclude individuals from participation. In all studies, daily buprenorphine maintenance doses ranged from 2 to 8 mg per 70 kg of body weight, based on the level of opioid dependence (

43). Subjects provided written informed consent after receiving a full explanation of the procedures.

Demographic and severity data

At patients' intake to the clinic, trained research assistants collected demographic information such as age, education, and gender and administered the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (

44) to all patients. ASI severity scores, ranging from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicative of more severe problems, were derived for the subscales of alcohol, drug, medical, social, legal, employment, and psychiatric problems. In these subscales, severity is defined as the number, duration, frequency, and intensity of symptoms. Previous research indicates that interrater reliability coefficients are high, ranging from .84 to .95 across the seven subscales, and test-retest correlation coefficients are .92 or above (

44). Discriminant validity is also adequate, with severity ratings on each of the subscales significantly correlating (p>.05) with other indexes of problems in that area (

44).

Therapists

Three master's-level staff clinicians with degrees in counseling psychology or social work and seven to ten years of experience as therapists provided the therapy. They had been employed by the clinic for one and a half to two years, and each provided therapy to between 32 and 43 patients. Assignment was based on current clinical caseloads, so that new patients entering treatment were assigned to the therapist with the lightest clinical load. Therapists received two hours a week of group supervision and one hour a week of individual supervision. Therapists were blind to the purposes of this study.

Therapeutic alliance

The Helping Alliance Questionnaire—Therapist Version (HAQ-T) is a 19-item inventory that measures the alliance between therapists and their patients, or the degree of a positive, helping relationship (

45). The items require responses from 1, strongly disagree, to 6, strongly agree. Five questions are negatively worded or related to negative interactions, and these items were reverse-coded. A total alliance score is computed by summing the responses, and scores can range from 19 to 114, with higher scores indicative of a more positive alliance.

This scale has adequate internal consistency, with correlations ranging from .90 to .93 (p>.001), and adequate test-retest reliability, with correlations ranging from .55 to .79 (p>) (

45). It also has covergent validity with the California Psychotherapy Alliance Scale, with correlations ranging from .59 to .80 (p>001) (

45).

The therapists completed the HAQ-T for each patient they saw for a minimum of three sessions. Only five patients were treated for less than three sessions, and they were not included in further analyses. For 46 of the 114 patients, the questionnaire was completed after the third therapy session. For the remainder of the patients, the questionnaire was completed retrospectively, after treatment termination. No statistically significant differences in HAQ-T ratings were noted between patients rated prospectively or retrospectively. The main analysis included the entire sample, and subsequent analyses were conducted including only patients for whom HAQ-T ratings were obtained after the third therapy session.

The Helping Alliance Questionnaire—Patient Version (HAQ-P) (

45) asks the same questions as the HAQ-T, but from the patient's perspective. All but three of the 46 patients who were followed prospectively completed the HAQ-P after the third therapy session. Patients completed the questionnaire in the dispensary, which was in a separate location from therapists' offices so that therapists could not see their responses. Directions on the questionnaire indicated that responses would not be shared with therapists. Patients did not know that their therapists were rating the alliance.

Treatment completion

The two detoxification studies consisted of a four-month study period during which patients were given and then tapered off buprenorphine, followed by naltrexone. These studies required patients to attend the clinic a minimum of three times a week, receive medication, and attend one to two hours a week of individual behavioral therapy. Therapy focused on triggers of drug use, functional analyses of drug use, relapse prevention, coping strategies for cravings, drug refusal skills, HIV education, and social and recreational training. Specifically, patients were taught to monitor their triggers and cravings for drugs and to develop alternatives to drug use. Patients also chose from optional training modules. Among the choices were modules on employment, education, parenting, anxiety, depression, pain management, and insomnia. Patients were discharged for failure to receive buprenorphine on three consecutive days or failure to initiate naltrexone therapy after the buprenorphine taper.

The other three studies were buprenorphine pharmacology studies, ranging from three to four months (

46,

47,

48). These studies examined different alternate-day dosing schedules of buprenorphine. Subjects were required to attend the clinic for all scheduled doses (between two and seven days a week), to remain abstinent from all opioids as assessed by urine specimens required two or three times a week, and to attend one to two hours a week of individual behavioral therapy, as described above. Subjects were discharged for failure to attend the clinic for a scheduled dose of buprenorphine or for submission of more than one opioid-positive urine sample.

Assignment to a detoxification or a pharmacology study was determined at intake to treatment by the clinic director, and it was based on the subject's preference and on the degree of opioid dependence. Patients with minimal levels of dependence were ineligible for pharmacology studies. Subjects were classified as study completers or noncompleters. No significant differences were noted between completion rates for detoxification and pharmacology studies; 62 percent completed detoxification and 53 percent completed pharmacology studies.

Data analysis

Differences between study completion rates, patient demographic characteristics, and baseline ASI scores were examined among the three therapists' caseloads using analysis of variance for continuous variables and chi square tests for nominal variables. Differences in HAQ-T and HAQ-P scores were also examined among the three therapists. To determine interrater reliability of ratings of alliances, correlations between patients' and therapists' alliance ratings were examined.

Univariate analyses were used to test differences between study completers and noncompleters in demographic characteristics, ASI severity ratings, and HAQ scores. These analyses were conducted using t tests for continuous variables and chi square tests for nominal variables.

Logistic regression was performed to examine unique contributions of these variables to whether subjects completed treatment. Demographic characteristics, ASI severity scores, clinic variables (study type, buprenorphine dose, and therapist), and HAQ-T scores and interactions of these variables were entered as independent variables. Treatment completion was the dependent variable.

Results

Comparison of therapists

The three therapists' caseloads did not differ in terms of any patient demographic characteristics or baseline ASI ratings. Study completion rates did not differ among the three therapists. Completion rates were 64 percent, 56 percent, and 47 percent for patients of therapists A, B, and C, respectively.

However, the therapists' ratings of their alliances with their patients differed significantly between therapists (F=4.01, df=2,113, p>.05). Therapist A had a mean±SD rating of 79±12 on the HAQ-T, which was significantly higher (p>.05) than those of the other two therapists. The mean±SD ratings were 74±10 and 69±23 for therapists B and C, respectively.

The strength of the therapeutic alliance as rated by the patients using the HAQ-P differed among the three therapists' patients, but the difference did not reach significance (p= .08). The highest mean±SD rating on the HAQ-P, of 96±14, was for therapist B, and the lowest, of 81±20, was for therapist A; the mean rating for therapist C, of 88±,17, was in between. Although patients tended to give higher ratings to the alliances than the therapists did, the therapists' and patients' ratings were related, with correlations between HAQ-P and HAQ-T scores ranging from .64 to .73 (p>.05).

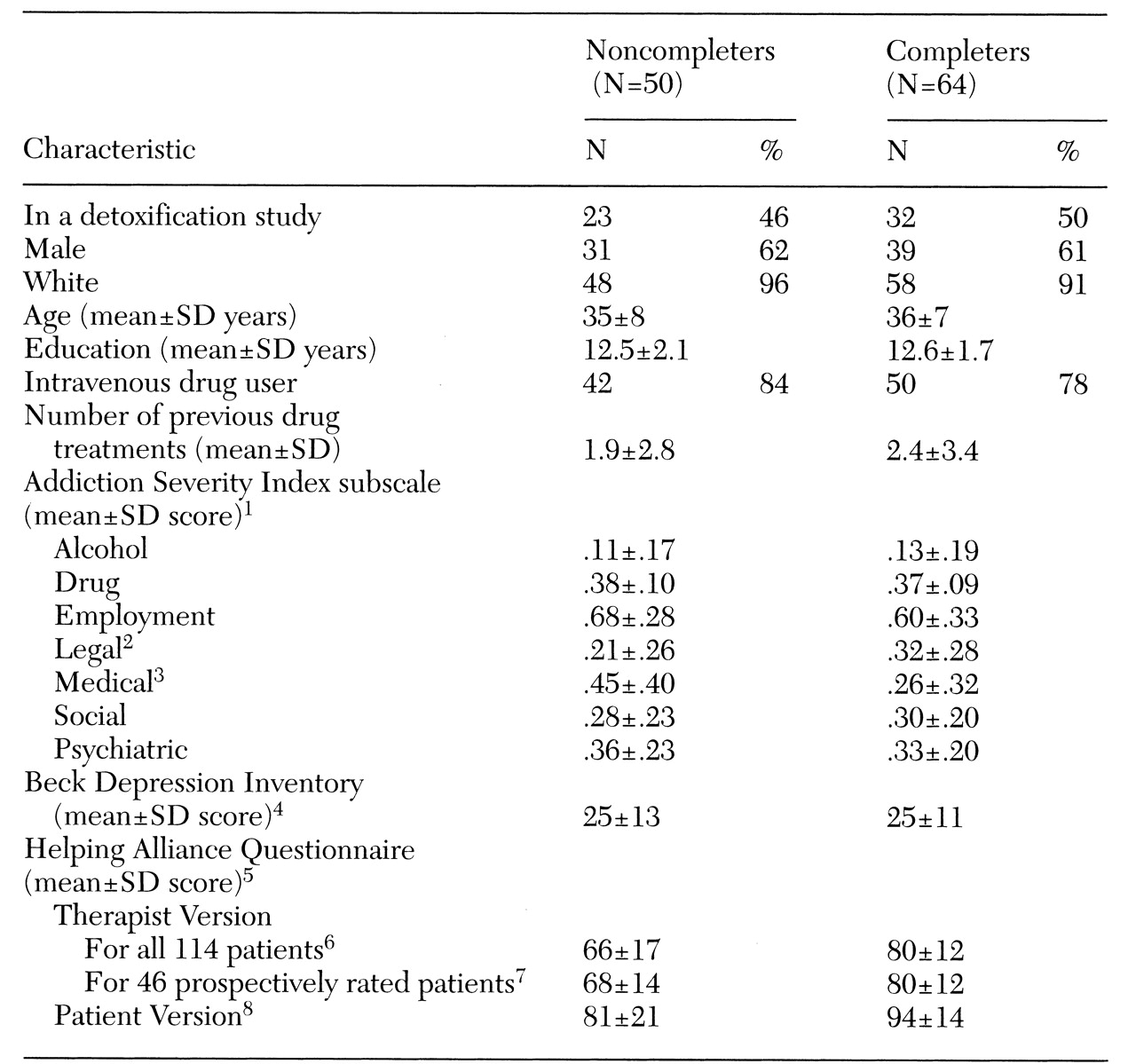

Comparison of completers and noncompleters

Table 1 presents characteristics of the study completers and noncompleters. The groups did not differ significantly in basic demographic characteristics, including gender, race, age, and education. A similar proportion of each group were intravenous drug users. The completers and noncompleters differed significantly on only two of 15 variables tested, ASI scores for legal and medical problems. Those who completed the studies had more severe legal problems and less severe medical problems.

Completers and noncompleters also differed significantly in the strength of the therapeutic alliance as rated by both the therapists and the patients. Compared with noncompleters, patients who completed treatment rated alliances higher, as did their therapists.

Logistic regression

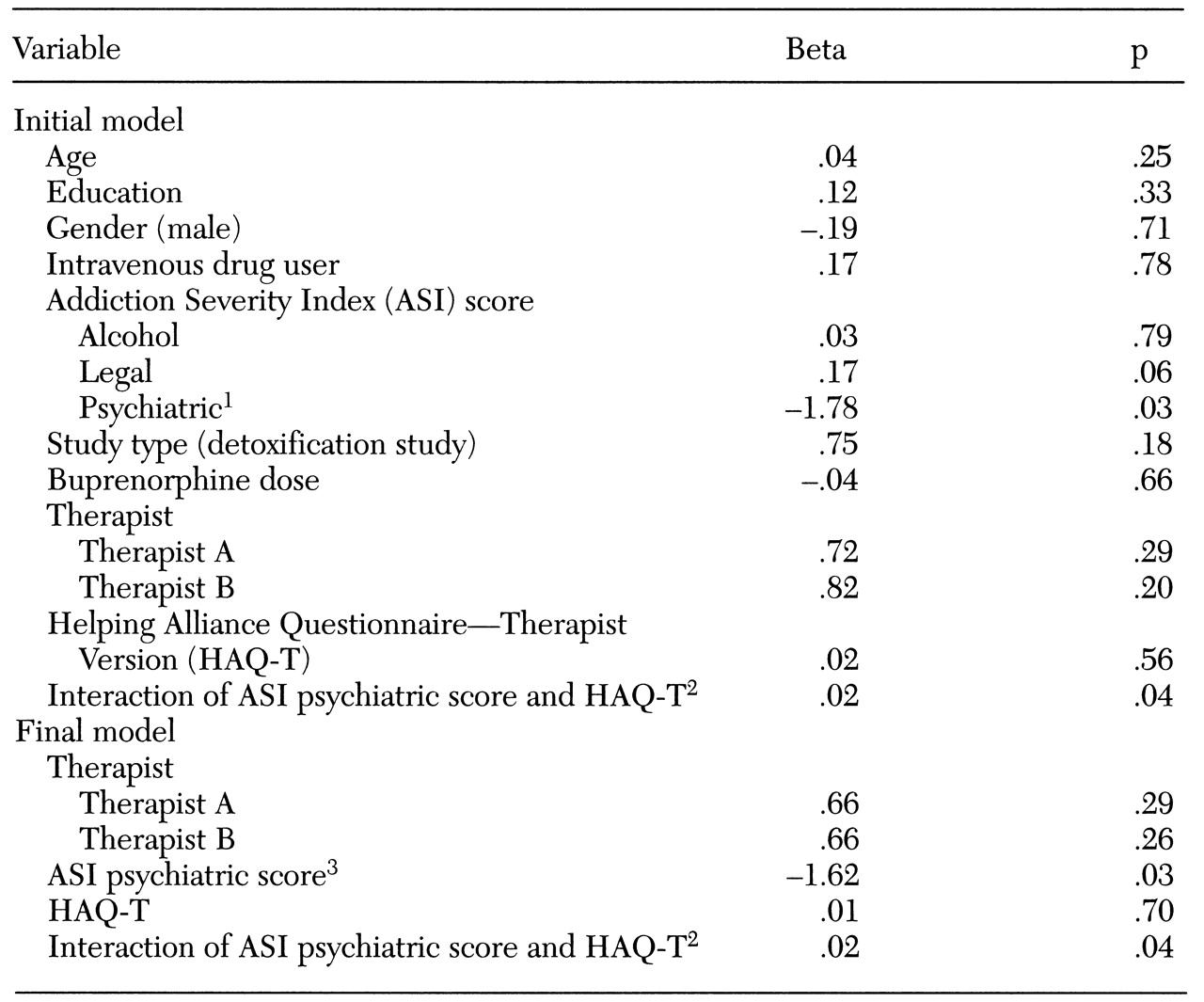

Table 2 shows the initial and final models testing the association of treatment completion status and certain variables, including ASI scores. The general procedure used in the development of the logistic regression model incorporated several steps to determine variables for inclusion in the final model. The first step was to enter basic characteristics and ASI severity ratings as one block into the logistic regression equation. For variables that were highly correlated with one another, such as employment and severity of legal problems, only one was included. The second step was to enter program variables into the equation, after controlling for the demographic characteristics. In the third step, the therapists' alliance ratings and the interaction between psychiatric severity and therapeutic alliance were entered.

Several iterations of model trimming were done to develop the most parsimonious model. Parameters not approaching statistical significance were dropped. After variables that best explained the variance were identified, variables that had been excluded from the original analysis due to multicollinearity (such as ASI ratings on employment and legal problems, and the ASI rating on drug problems and intravenous drug use) were substituted into the equation, and analyses were rerun.

Model 1 included age, education, gender, and intravenous drug use and only three ASI ratings—alcohol, legal, and psychiatric severity scores. The three subscales were chosen because they have been associated with treatment retention in previous studies (

19,

20,

21,

37) and because they did not correlate with one another. Gender and intravenous drug use were coded as dummy variables. The likelihood ratio test indicated that this model did not predict study completion.

Model 2 addressed whether program-specific variables (therapist assignment, type of study protocol, and buprenorphine dose) predicted completion status, after controlling for the previously described variables. The likelihood ratio test indicated that this model also failed to predict study completion.

Model 3 examined whether therapists' ratings of the alliance (HAQ-T scores) and the interaction between the therapeutic alliance and psychiatric severity were significantly associated with treatment completion, after controlling for the other variables. Inclusion of this step resulted in an equation that significantly predicted treatment completion (χ2=37.5, df= 13, p>.001 for the model, and χ2= 27.3, df=2, p>.001 for the block). More than 75 percent of the cases were correctly identified by this model as completers or noncompleters.

After other variables were adjusted, ASI scores on psychiatric severity were significantly related to treatment completion (Wald statistic= 4.80, p>.05), and patients with fewer psychiatric symptoms were more likely to complete treatment. When the analysis adjusted for other variables, therapeutic alliance was not associated with completion status, but the interaction between psychiatric severity and therapeutic alliance was associated (Wald statistic=4.25, p>.05). Patients with more severe psychiatric symptoms were more likely to complete treatment if they had a strong alliance, but alliance was not related to completion among patients with less severe psychiatric symptoms.

These models were repeated removing terms that were not significantly associated with treatment completion. Both the initial and the final models are shown in

Table 2. The final model was robust, in that key variables of interest did not vary appreciably with inclusion or exclusion of other variables, such as adding ASI scores on the drug or social subscales; substitution of other highly correlated variables, such as legal ASI score for employment ASI score; or removal of nonsignificant variables, such as gender, education, intravenous drug use, and buprenorphine dose. Although other possible interactions between alliance measures and other variables were examined, none were significant.

Interaction between psychiatric severity and alliance

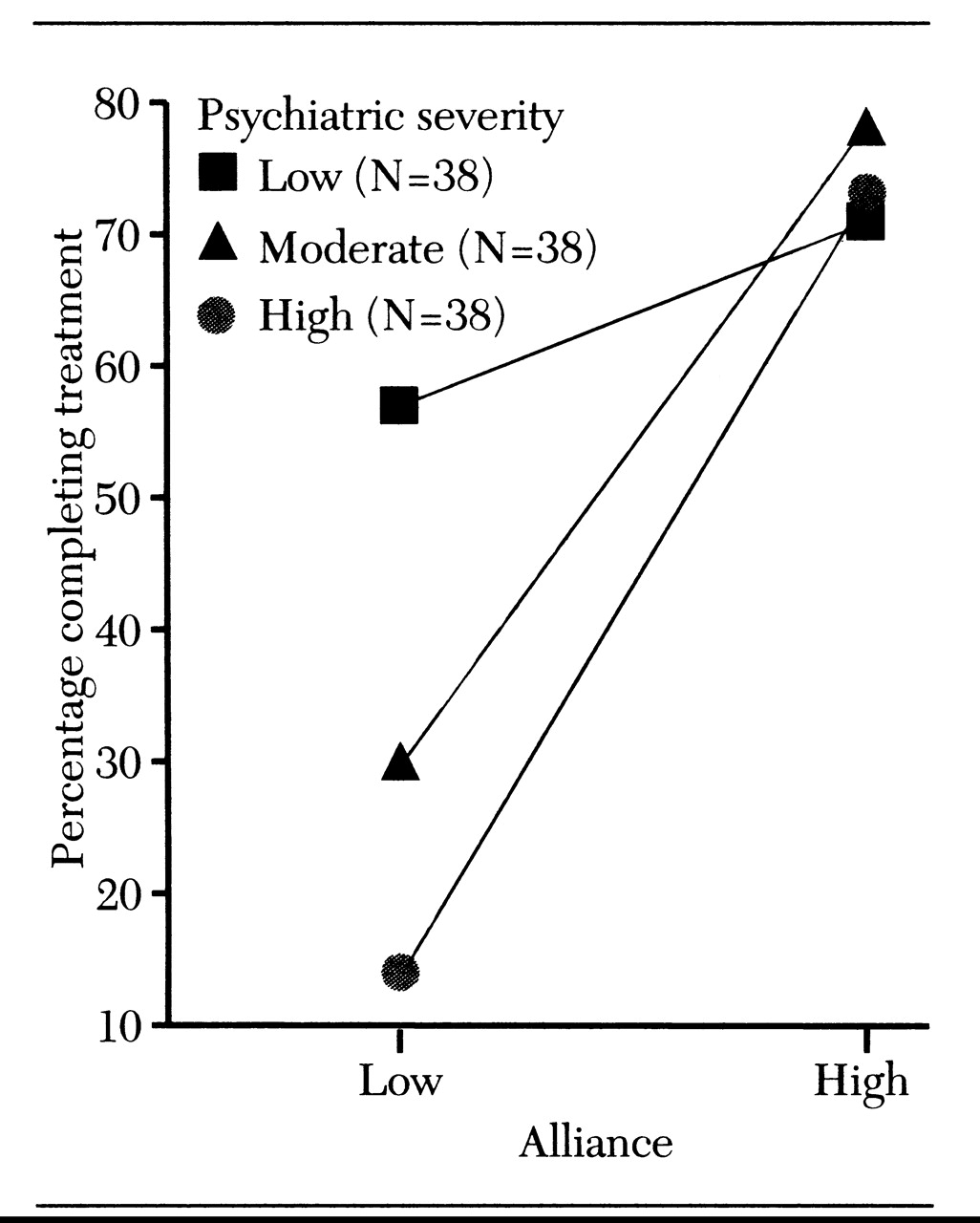

Patients were grouped into one of three categories based on psychiatric severity, with 38 patients in each group: those with ASI scores in the lowest third of the sample (scores of 0 to .21), in the middle third (scores of .22 to .48), or in the highest third (scores of .49 to 1). The alliance between the therapists and each of their patients was ranked as either above or below the median of the alliances for that therapist.

Figure 1 shows that therapeutic alliance did not affect study completion among patients with few psychiatric symptoms. However, the therapeutic alliance was related to treatment completion among patients who had psychiatric problems that were moderate or severe. Only 23 percent of patients with moderate to severe psychiatric symptoms and a below-average alliance completed treatment. In contrast, more than 75 percent of patients with moderate to severe psychiatric problems but an above-average alliance completed treatment. This trend was similar for all three therapists (data not shown).

The interaction effect was maintained when the analysis included only the 46 patients who were followed prospectively. HAQ-T scores were not related to study completion of patients with relatively few psychiatric symptoms. However, among patients with moderate to severe psychiatric problems, 30 percent with low-rated alliances completed treatment versus 80 percent with high-rated alliances. Chi square analyses revealed that alliance was significantly associated with treatment completion among patients with moderate to severe psychiatric problems (χ2=8, df= 1, p<.01).

Among the 46 patients followed prospectively, 43 completed the HAQ-P. Analysis of their ratings of the therapeutic alliance provided further support for these findings. HAQ-P scores were not associated with treatment completion among patients with few psychiatric problems. Seventy-five percent of those with alliances below the median completed treatment, and 67 percent of those with alliances above the median completed treatment. Among those with moderate and severe psychiatric problems, the relationship between study completion and therapeutic alliance approached but did not reach statistical significance (p=.06). Fifty percent of patients who reported relatively weak alliances completed treatment versus 85 percent of those who reported relatively strong alliances.

Discussion and conclusions

This study examined the relationship between patient variables, ASI severity ratings, program-specific variables, and the therapeutic alliance in predicting treatment completion among opioid-dependent individuals in an outpatient research and treatment clinic. The data indicate that only psychiatric severity and the interaction between psychiatric severity and therapeutic alliance predicted treatment completion. These findings, and several issues that may bear on the interpretation of the findings, are discussed.

The three therapists' caseloads did not differ in any demographic characteristics or ASI severity ratings. This lack of difference was expected, because new patients were arbitrarily assigned to therapists. In addition, treatment completion rates did not differ among the three therapists' caseloads, suggesting that the three therapists were equally efficacious in retaining patients in the studies.

However, significant differences in HAQ-T scores were noted among the three therapists. These differences suggest either that the three therapists had differential response biases in filling out the questionnaire (for example, therapist A was most likely to strongly endorse positive items) or that the alliances between patients and therapists differed among the three therapists. Patients' ratings indicated that therapist B tended to have the strongest relationships with patients and therapist A the weakest. Because of these differences in HAQ ratings among the therapists, subsequent analyses controlled for a therapist effect.

To examine the unique variance that therapeutic alliance, patient characteristics, and symptom severity may explain in predicting treatment completion, logistic regression analysis was conducted. After the analysis controlled for other variables, only psychiatric severity and the interaction between psychiatric severity and therapeutic alliance significantly predicted treatment completion. Specifically, patients with moderate to severe psychiatric symptoms were less likely to complete treatment. The interaction term indicated that patients with few psychiatric problems were equally likely to complete treatment, regardless of whether they had strong or weak alliances with their therapists. In contrast, a strong alliance was associated with a completion rate three times higher among patients who presented with moderate to severe psychiatric symptoms.

These results both confirm and extend previous findings of the roles of psychiatric severity and therapeutic alliance in treatment retention. Several studies of substance abusers have found better retention rates among those with fewer baseline psychiatric problems (

35,

36,

37). In terms of the role of the therapeutic alliance, Luborsky and colleagues (

39,

41) have shown repeatedly the predictive validity of the HAQ in the treatment responsiveness of substance abusers as well as other psychiatric populations. The data from the study reported here integrate these findings and suggest that the therapeutic alliance is particularly important in predicting treatment retention among opioid-dependent individuals with moderate to severe psychiatric problems.

These results are consistent with those recently reported by Carroll and colleagues (

49). They found that a strong alliance was important in treatment outcome among cocaine-dependent patients assigned to "control" therapies, but alliance did not predict outcome among patients assigned to enhanced therapies. To the extent that receiving enhanced therapies, like having few psychiatric problems, leads to improved outcomes, a strong alliance seems to exert influence on outcome among patients who are less likely to succeed on their own. Whether these results hold for other substance-abusing and psychiatric populations remains to be determined.

Although these conclusions have intuitive appeal and are consistent with past research, the findings may be affected by several factors. One potential criticism of these findings is that the ASI psychiatric composite score, rather than structured clinical diagnoses, was used to assess psychiatric status. However, this scale score is highly correlated with scores on the Beck Depression Inventory, the Maudsley neuroticism scale, and the Symptom Checklist-90 (

37). In the study reported here, pretreatment Global Severity Index scores from the Symptom Checklist-90 were available for 77 patients and correlated (r

2=.46, p<.001) with ASI psychiatric scores. Thus in both this sample and previous samples of opioid-dependent patients, ASI psychiatric scores are indicative of global psychiatric status. However, patients with the most severe psychiatric problems, such as active psychosis, were screened out before admission to treatment or may have been discharged before receiving three therapy sessions. Thus these findings are representative only of patients who remained in treatment at least two weeks.

One weakness of the study was that the therapeutic alliance was retrospectively rated for the majority of the patients and thus may have been influenced by therapists' knowledge of whether the patient completed treatment. Similarly, patients who were retained in treatment longer may have been more likely to develop a stronger relationship with their therapist. However, post hoc analyses including only patients who were followed prospectively confirmed the main finding of a stronger alliance being important for successful treatment completion among patients with moderate to severe psychiatric problems. Other prospective research using the HAQ also indicates that both therapists and patients have an early mutual sense of the therapeutic alliance and that does not change appreciably over time (

45).

Another potential limitation of the findings is that the dependent variable of interest was defined as a dichotomous variable: completion or noncompletion of a three- to four-month research study. Other studies have used pre- and posttreatment evaluations of drug use and psychosocial functioning as outcome measures (

16,

18,

22,

2735,

36,

44), and these measures may better assess efficacy of treatment across a range of domains. In the study reported here, such data were not collected for all subjects across all trials, and thus treatment completion was used as the dependent variable. Nevertheless, completion of a three- to four-month treatment program such as the protocols in which these subjects participated may be considered a clinically important outcome measure. In previous studies, Simpson and colleagues (

50,

51,

52) found that drug abusers who spent less than three months in treatment programs had the least favorable outcomes.

In the study reported here, subjects were required to attend the clinic regularly and provide opioid-negative urine samples to be permitted to continue in these trials for three to four months. The bulk of evidence suggests that treatment retention in opioid substitution programs is associated with a variety of positive outcomes, including reductions in opioid and other illicit drug use (

6), decreases in criminal activity (

9), improvements in psychosocial functioning (

12), and reductions in HIV risk-taking behaviors (

10). Further research may more clearly delineate the effects of the therapeutic alliance and psychiatric symptoms in improving these variables during substance abuse treatment.

Other limitations of this study include the small sample size of therapists and the research nature of the clinic in which the study was conducted. Only three therapists were studied, but similar trends were found for all three. In other words, all three equally retained patients with few psychiatric symptoms in the research protocols, regardless of the alliance.

In addition, for patients with moderate and high levels of psychopathology, increases in study completion rates were found for all three therapists only when a strong relationship was formed. These similar results across therapists may have resulted from the highly structured therapy that was provided in conjunction with buprenorphine, an efficacious opioid agonist. Future research should examine whether these results can be replicated with a larger sample of less experienced therapists and when other psychotherapies are provided, both with and without pharmacotherapy.

In summary, these data indicate that psychiatric severity and the interaction between psychiatric severity and therapeutic alliance are associated with treatment completion among opioid-dependent individuals. If the results are replicated in prospective studies using a larger sample of therapists and a greater variety of outcome measures, they may have important implications for treating opioid-dependent individuals.

Specifically, the results suggest that patients with few psychiatric problems tend to stay in treatment, regardless of their relationship with their therapist. However, perhaps greater efforts should be expended on developing a positive helping alliance with patients who have moderate and severe psychiatric problems. The data indicate that these patients are not likely to remain in treatment unless they develop a strong therapeutic relationship with their therapist.

Because the helping alliance is established by the third therapy session (

45), patients with psychiatric problems should be closely monitored. Perhaps patients who do not develop a positive relationship early in treatment could be transferred to a new therapist, with whom they may be more likely to develop a positive rapport. Prospective clinical trials are needed to assess this strategy in improving retention in substance abuse treatment programs.

Although this study did not have an adequate sample of therapists and patients to investigate demographic and other personal qualities of both that may be relevant to a strong alliance, other studies have begun to address this issue. These factors may include demographic similarities between patient and therapist (

53), the patient's degree of involvement in therapy (

54), and mutual patient-therapist understanding (

55).

A better understanding of the characteristics and processes that result in the development of a positive therapeutic alliance may help improve treatment retention of opioid-dependent patients, especially those with greater psychiatric problems, who are among the most difficult to treat. Given the high prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders and early treatment termination among substance abusers (

17), the drug abuse treatment and public health communities may benefit from expanded efforts to understand and maximize the effectiveness of dynamic patient-therapist variables that are associated with retention in treatment programs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Bruce Brown, M.S.W., Marne Moegelin, M.A., and Tyler Wood, M.A., for providing therapy, Melissa Foster, Elizabeth Kubik, Bonnie Martin, Richard Taylor, and Evan Tzanis for collecting data, and Alan Budney, Ph.D., Joe Burelson, Ph.D., Henry Kranzler, M.D., and Howard Tennen, Ph.D., for providing helpful comments. This research was supported by grants T32DA07242, R01DA06969, 2R01DA06969-Supp, and R29DA12056 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and grant 5P50-AA03510-19 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.