A recent study reported that 14.5% of men and 31.0% of women booked in five county jails (three in New York and two in Maryland) had a serious mental illness (

1). The authors estimated that if these figures were applicable to arrestees in the United States, 2,161,705 individuals among the 13 million arrestees booked into U.S. jails in 2007 would have a serious mental illness at the time of arrest. Many of these individuals return to communities with inadequate treatment capacity, housing, and social welfare services, and many are rearrested, jailed, and ultimately returned to those same communities, where the cycle may begin anew (

2). However, even where adequate services exist, many people returning to the community from jail and prison lack the means to pay for services or do not qualify for entitlement programs, such as Medicaid, that might provide a funding stream for service providers (

3).

Medicaid enrollment can be an important part of successful community reentry from jail. A study conducted in King County, Washington, and Pinellas County, Florida, found that individuals enrolled in Medicaid at the point of release from jail had better access to services and fewer rearrests than comparable unenrolled persons (

4). Based in part on such findings, programs have been developed to assist individuals in applying for entitlements while still in jail (

5).

Although policy makers have begun to focus on the importance of Medicaid and other entitlements as part of community reentry, little is known about the size of the potential target population. For example, how many arrestees have been enrolled in Medicaid before their arrest, and how many have a history of Medicaid-reimbursed mental health or substance abuse service use? As important, how many of those who had used such services were still eligible at the time of arrest?

One practical reason little is known about these questions is that databases containing arrest information and Medicaid claims files typically are held by different agencies and there is no single entity with the access and technical capacity to integrate them. However, in Florida access to both statewide arrest files and Medicaid claims files is available to the University of South Florida through agreement with the Florida agencies responsible for them. Using these statewide databases, we conducted analyses designed to address the following questions. First, how many people arrested in Florida in fiscal year (FY) 2006 were enrolled in Medicaid in the 365 days before their arrest? Second, how many of those individuals had used Medicaid-reimbursed mental illness or substance abuse treatment services during that period? Third, how many of the individuals enrolled in Medicaid, including those using Medicaid-reimbursed behavioral health services in the 365 days before their arrest, remained enrolled in Medicaid when arrested?

Methods

The analyses relied on two statewide administrative data sources: Florida arrest information kept by the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, which includes records of individuals arrested in Florida and is made available through a memorandum of understanding with the Florida Criminal Justice, Mental Health, and Substance Abuse Technical Assistance Center at the Florida Mental Health Institute, and Florida Medicaid claims data, which were made available to the Florida Mental Health Institute under contract with the Florida Agency for Health Care Administration, which administers Florida's Medicaid program.

All data management and analyses were conducted in SAS, version 9.1. Individuals were linked across these two systems by using public domain record linkage and consolidation software called the Link King (

www.the-link-king.com), which is written in SAS and uses probabilistic and deterministic linkage protocols. Descriptive analysis was used to answer the first question and then general linear model regression models were used to examine the relationships for both number of arrests and number of Medicaid services with gender, race or ethnicity, and age at arrest.

Diagnoses of mental and substance use disorders and use of services were based on ICD-9 diagnosis codes (290.00–319.00) in individuals' Medicaid claims files. For our purposes, serious mental illness included schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, mood disorders, delusional disorders, bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, major depressive disorder, and nonorganic psychoses.

Results

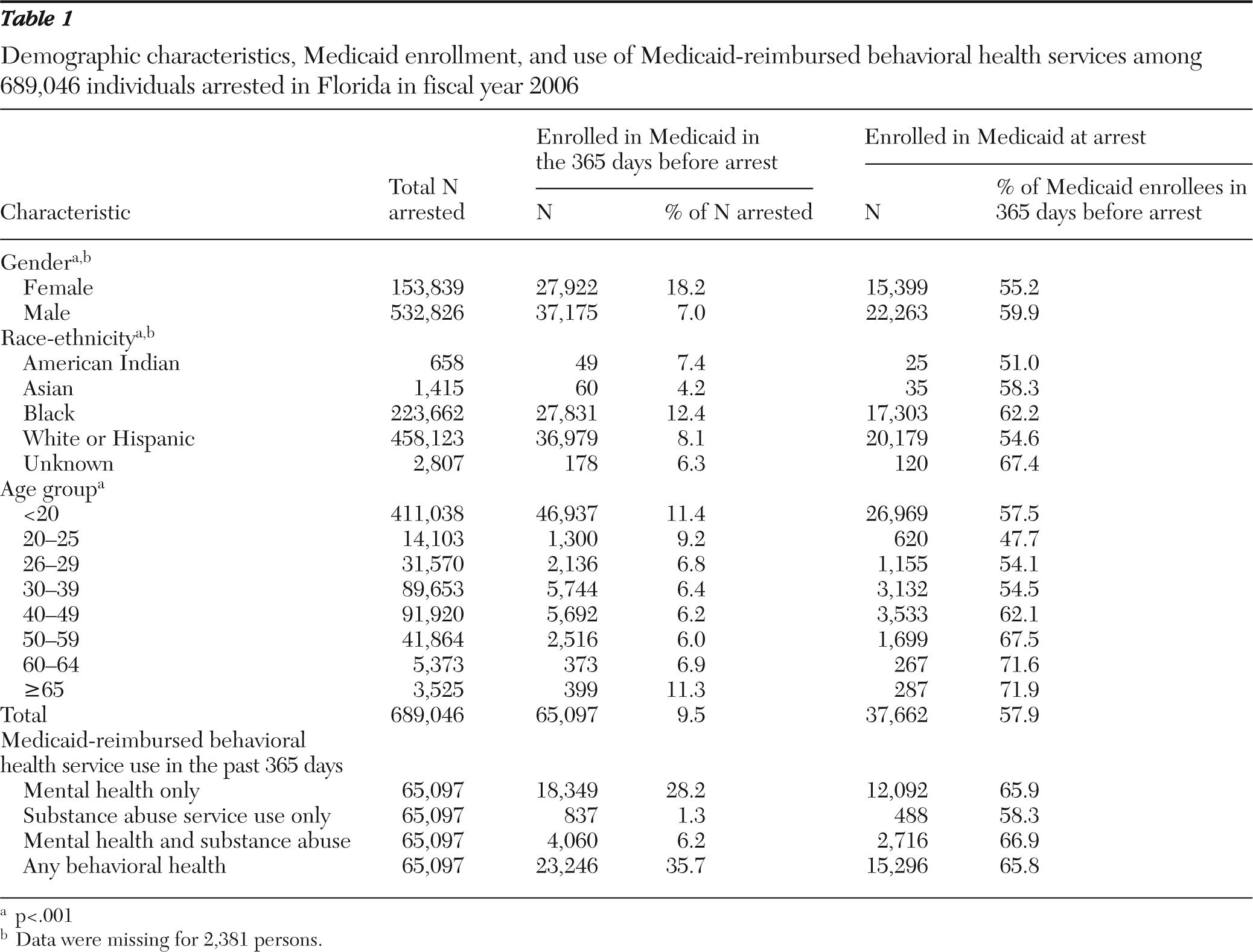

Results are presented in

Table 1. A total of 689,046 individuals were arrested in Florida during FY 2006. Demographic information was unavailable for 2,381 individuals (<.3%) and they are not included in analyses of race and gender. Roughly one-quarter (N=153,839, 22.4%) were female, and 532,826 (77.5%) were male. Among those arrested, 223,662 (32.5%) were black and 458,123 (66.5%) were white or Hispanic. Blacks were overrepresented among arrestees relative to the overall population of Florida, which according to 2006 census data was 12.8% black.

Among all arrestees, 65,097 (9.4%) had been enrolled in Medicaid at some point within the 365 days before arrest. In Florida in 2006, a total of 1,027,737 individuals between the ages of 18 and 64 were enrolled in Medicaid (6.0% of the general population). There were significant gender differences in enrollment among arrestees: among the women arrested, 18.2% were enrolled in Medicaid in the 365 days before arrest, compared with 7.0% of the men arrested. However, as a percentage of all arrestees enrolled in the 365 days before arrest (N=65,097), the proportion of men was higher: 57.1% compared with 42.9% of women. Among black arrestees, 12.4% were enrolled in Medicaid in the past 365 days, compared with 8.1% of white arrestees. As a percentage of all arrestees enrolled in the 365 days before arrest, the proportion of blacks was lower: 42.8% compared with 56.8% of whites. Few arrestees (N=1,415, <.2%) were Asian, and only 60 Asian arrestees (4.2% of Asian arrestees) had been enrolled in Medicaid in the prior 365 days.

Among Medicaid enrollees, 23,246 individuals (3.4% of all arrestees; 35.7% of those enrolled in Medicaid) used at least one Medicaid-reimbursed behavioral health service in the 365 days before arrest. The vast majority of this service use was for mental health services alone (N=18,349, or 78.9% of those who had used behavioral health services), rather than substance use services alone (N=837, or 3.6% of those who had used behavioral health services). A larger number used both mental health and substance abuse services paid for by Medicaid (N=4,060, or 17.5% of those using behavioral health services). Of those using behavioral health services, 5,927 (25.5%) had a diagnosis of a serious mental illness.

Of the 65,097 individuals enrolled in Medicaid in the 365 days before their arrest, 37,662 (57.9%) were still enrolled at the time of arrest. This means that 27,435 (42.1%) were no longer enrolled when arrested. Men were more likely than women to be enrolled at the time of arrest (22,263 men, or 59.9% of those enrolled in the prior 365 days, versus 15,399 women, or 55.2%). Blacks were more likely than whites or Hispanics to be enrolled at the time of arrest (17,303 blacks, or 62.2%, versus 20,179 whites or Hispanics, or 54.6%). Of the 23,246 individuals who had used Medicaid-reimbursable behavioral health services, 15,296 (65.8%) were still enrolled at the time of arrest; among those not using behavioral health services, 22,366 (53.4%) were still enrolled at the time of arrest.

After completing these analyses we ran a post hoc analysis to ascertain whether disenrollment among arrestees and nonarrestees was comparable (data not shown in table). Using July 1, 2007, as the end point, we found that 82,897 nonarrested individuals between the ages of 18 and 64 had used Medicaid-reimbursable behavioral health services in the prior 365 days. On July 1, 2007, 65,735 (79.3%) were still enrolled (26,085 of 32,345 men, or 80.6% of previously enrolled men; 39,647 of 50,522 women, or 78.5% of previously enrolled women). This contrasts with a retention rate at the point of arrest of 57.9% in the arrested population. Although additional analyses comparing disenrollment among arrested and nonarrested populations are warranted, this preliminary post hoc analysis suggests that among those using Medicaid-reimbursed behavioral health services, disenrollment occurred at a higher rate among arrestees.

Discussion

Medicaid enrollment as part of community reentry for persons with serious mental illness has emerged as an important issue (

6). The data presented here provide the first glimpse of Medicaid enrollment in a statewide cohort of arrestees and attrition in enrollment at the point of arrest. There are many factors that can lead to Medicaid disenrollment, and further analyses will help explore these factors. For example, have some of these individuals found jobs and received insurance through their employers? Have some qualified for Medicare, which providers may be encouraged to bill first? Have some lost family relationships, which may have terminated their eligibility? Others, particularly those who are younger, may have aged out of eligibility. It is interesting that a preliminary analysis of a nonarrested cohort that had used behavioral health services revealed much higher retention in enrollment than among arrestees. It is also interesting that among arrestees, those who had used Medicaid-reimbursable behavioral health services had a higher rate of retention than those who had not (65.8% versus 53.4%). More comparative analyses examining whether and why these patterns persist are warranted.

These data also suggest that Medicaid is little used among people with mental illnesses arrested in Florida, relative to the probable prevalence of serious mental illnesses in that population. Less than 4% of all arrestees had used Medicaid-reimbursable behavioral health services in the 365 days before arrest, a rate far below current prevalence estimates of serious mental illness among arrestees. And only 837 people (1.3%) had used Medicaid-paid substance abuse services alone, reflecting the general fact that Medicaid is of little current value in obtaining the substance abuse services that the vast majority of criminal justice-involved individuals could use. Finally, given the importance of Medicaid as a tool for gaining access to services upon release from jail (

4,

6), these data suggest that a potential target population for efforts to assist incarcerated individuals might be those who had been on Medicaid previously but were no longer enrolled when arrested. Presumably, although subject to additional analysis, such individuals may more readily qualify for enrollment than other individuals in the general inmate population.

This analysis was limited to two statewide data sets (arrest data and Medicaid claims files), so data on services not funded by Medicaid were not included. In addition, the data did not reveal why individuals were no longer enrolled in Medicaid at the time of arrest. Also, further analyses are required to determine whether an arrested population differs significantly from a comparable nonarrested population in enrollment attrition, and much more needs to be learned about pre- and postarrest use of services by arrestees with mental illnesses who are continuously on Medicaid versus those whose Medicaid enrollment is interrupted or terminated.

Conclusions

Despite limitations, this study begins to shed light on Medicaid penetration rates among arrestees, use of behavioral services among Medicaid enrollees, and the decline in enrollment at the point of arrest. These findings may have relevance for programs designed to increase access to entitlements for people in jail, which is important given the apparent impact of Medicaid enrollment on access to services when reentering the community from jail (

3,

4,

6).

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported partially by a contract with the Florida Agency for Health Care Administration. The original data were collected through a memorandum of understanding with the Florida Department of Law Enforcement and a contract with the Florida Agency for Health Care Administration.

The authors report no competing interests.