Military personnel are at high risk of exposure to potentially traumatic events and, as a consequence, may be particularly susceptible to mental health problems. Research findings based on the most recent cohort of veterans returning from Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) suggest that veterans may experience a range of mental health problems, including, especially, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and generalized anxiety (

1–

5). In one recent study, approximately one-third of returning OEF-OIF soldiers experienced major depression, PTSD, suicidal ideation, interpersonal conflict, or aggressive ideation approximately six months after returning from deployment (

4).

Despite extensive efforts on the part of both military and Veterans Health Administration (VHA) leadership to enhance access to mental health services for military personnel and veterans, research findings indicate that many returning war veterans do not seek out needed services. For example, in one study of OEF-OIF veterans identified as having serious mental health problems, only between 23% and 40% reported having sought mental health care, and less than half indicated an interest in receiving mental health care (

1). In a more recent study, less than half (42%) of OIF military personnel referred for mental health care after deployment received follow-up care, and over one-third (39%) of those referred for mental health care six months later did not pursue follow-up care (

4). Thus it appears that the use of mental health services among military personnel and veterans does not parallel expected prevalence and need, underscoring the importance of efforts to identify factors that influence mental health service use within these populations.

One factor that may be especially salient with respect to understanding why veterans do or do not seek out needed mental health services is a veteran's beliefs about mental health and mental health treatment. In particular, concerns about public stigma, as reflected in the extent to which an individual believes that he or she will be stigmatized by others for having a mental health problem, as well as personal beliefs about mental illness and mental health treatment, may have implications for service use. This conceptualization draws from research on attitudes toward mental health care among the general public by Corrigan and colleagues (

6,

7), who have focused on both public stigma, defined as the general society's reaction to people with mental illness, and self-stigma, reflected in the internalization of negative beliefs about mental illness. Findings based on research with the general public indicate that concerns about public stigma may be a powerful deterrent to service use. For example, “concerns about what others would think” was identified as a key barrier to the use of treatment in the National Comorbidity Survey (

8), and 24% of adults who reported unmet need for mental health care identified stigma avoidance as a barrier to care in another large nationally representative sample (

9). Similarly, Sirey and colleagues (

10) found that beliefs about devaluation and discrimination toward individuals with mental illness were negatively related to treatment adherence in a sample of adults who had been prescribed antidepressant medication.

Evidence from the literature on the general population also suggests that an individual's own beliefs about people with mental illness may have important implications for service use. For example, Cooper and colleagues (

11) found that people who endorsed the belief that individuals with psychiatric problems are responsible for their disorders and who reacted to those individuals with anger were less likely to seek care for themselves when they needed it. Beliefs about mental health treatment also appear to be implicated in service use. For example, Kessler and colleagues (

8) found that among those who recognized a need for treatment, 45% reported perceived lack of effectiveness as a reason for not seeking treatment, and 19% of adults who indicated an unmet need for mental health care as part of Ojeda and Bergstresser's (

9) study of a large nationally representative sample identified negative attitudes about treatment seeking as an obstacle to care.

The goal of this study was to review the literature on beliefs about mental health in regard to service utilization among military and veteran populations and to identify conceptual and methodological issues that warrant additional attention in future research in this area. This article fills an important need by being the first to provide a critical review of this literature. Included in the review were studies that fall within two categories: those that examined how concerns about public stigma relate to mental health service use and those that focused on how personal beliefs about mental illness and mental health treatment relate to mental health service use. To set the stage for this review, a brief overview of the literature on barriers to care for military personnel and veterans is provided next, and the relevance of mental health-related beliefs for these populations is discussed.

Research on barriers to care in military and veteran populations

Research on barriers to care for military personnel and veterans has burgeoned over the past several decades, revealing a number of factors that substantially affect service use and health outcomes (

12–

17). Many of these studies have applied Andersen's original model (

18) to address characteristics of an individual that influence his or her likelihood to seek out mental health services. According to this model, use of services is a function of background characteristics that increase or decrease the likelihood that one will use them (predisposing factors), social circumstances that have an impact on ability to seek care (enabling or impeding factors), and factors that reflect one's need for health care based on health status and functional impairment (need-based factors). Military and veteran studies that have applied the Andersen model have addressed factors such as sex (

15,

19), age (

20), service-connected disability status (

19–

21), and need for health care, as reflected in mental and physical health symptoms (

22,

23). Findings have revealed a number of background characteristics that are associated with increased service use. For example, prior research on the VA health care setting has shown that being male (

19,

24,

25), being older (

20,

21), having a service-connected disability (

21), and having more severe health problems (

20) are all predictors of more service use.

A separate line of research has focused on characteristics of the health care environment that may increase or decrease use of services, such as the availability of services and ease of accessing care. Much of this research has focused on the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care environment (

12,

13,

26,

27). Findings from the literature indicate that perceptions of service availability play a key role in predicting utilization of VA health care. For example, among female veterans, perceptions of the availability of services have been found to contribute unique variance in the prediction of VA health care use above and beyond individual factors known to differentiate current from former users of VA health care (

27). Results from samples that include men also indicate that waiting times and paperwork are perceived as significant barriers to VA health care (

13,

28). Consistent with this perspective, among users of VA health care, difficulty navigating the health care system has been identified as a relevant barrier to care (

12).

Another potentially relevant barrier to care for military and veteran populations is personal beliefs about mental illness and mental health treatment. As discussed above, mental health-related beliefs have been identified as a key contributor to mental health service use within the broader literature on the general population (

29), and negative beliefs about mental health treatment may be an even more powerful deterrent to service use in military and veteran populations. Because of the high value placed on emotional strength in the military, including, for example, the ability to “tough out” difficult emotions (

30), military and veteran populations may be more susceptible than civilians to negative beliefs about mental illness and mental health treatment. The relevance of mental health attitudes among military and veteran populations is further underscored by the fact that the military includes a large proportion of young men, a group that may be especially susceptible to negative beliefs about mental health treatment seeking (

31–

34).

Concerns about public stigma may also be compounded among military personnel to the extent that individuals who experience mental health problems fear negative career consequences. In contrast to the civilian workplace, in which mental health records are typically not available to supervisors, in the military each service member's commanding officer has access to his or her mental health records, and those who are seen as “unfit” for service may be discharged or removed from duty (

31). There is also some evidence that concerns about potential career consequences associated with having mental health problems may continue to plague military personnel who have left service. For example, in a recent focus group study with OEF-OIF veterans, fear that VHA mental health records would be accessible to potential federal and state employers was raised as a significant concern of several participants (

35). Consistent with this finding, preliminary study findings based on a small sample of female veterans of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan revealed that 36% of female veterans who sought care outside the VHA identified concern about harming their career as a reason for their decision (

36).

The next section summarizes the military and veteran literature on mental health beliefs about service use. Gaps in the literature are discussed, and recommendations for future research are provided.

Methods

A review of PsycINFO and PubMed bibliographic databases was conducted in September 2009. PsycINFO provides abstracts and citations to the scholarly literature in the psychological, social, behavioral, and health sciences from 1806 to the present. PubMed comprises more than 19 million citations in the fields of medicine, nursing, dentistry, veterinary medicine, the health care system, and preclinical sciences. PubMed, which includes articles from 1879 to the present, provides access to MEDLINE and to citations for selected articles in life science journals not included in MEDLINE. All available journal articles in both search engines were included in this review. The primary search terms that were used for this review were “attitudes” or “beliefs” or “stigma,” “mental health” or “mental illness,” and “military” or “veteran.” In addition, a search of

www.google.com was conducted to identify any articles that were recently published but that had not yet been indexed in PsycINFO and PubMed, and colleagues who were known to be studying mental health-related beliefs in military or veteran populations were consulted to identify any additional articles accepted for publication but not yet published (“in press”). Only articles that reported either qualitative or quantitative data based on military or veteran samples were included in this review. All articles that were identified as “under review” or “in preparation” were excluded.

Results

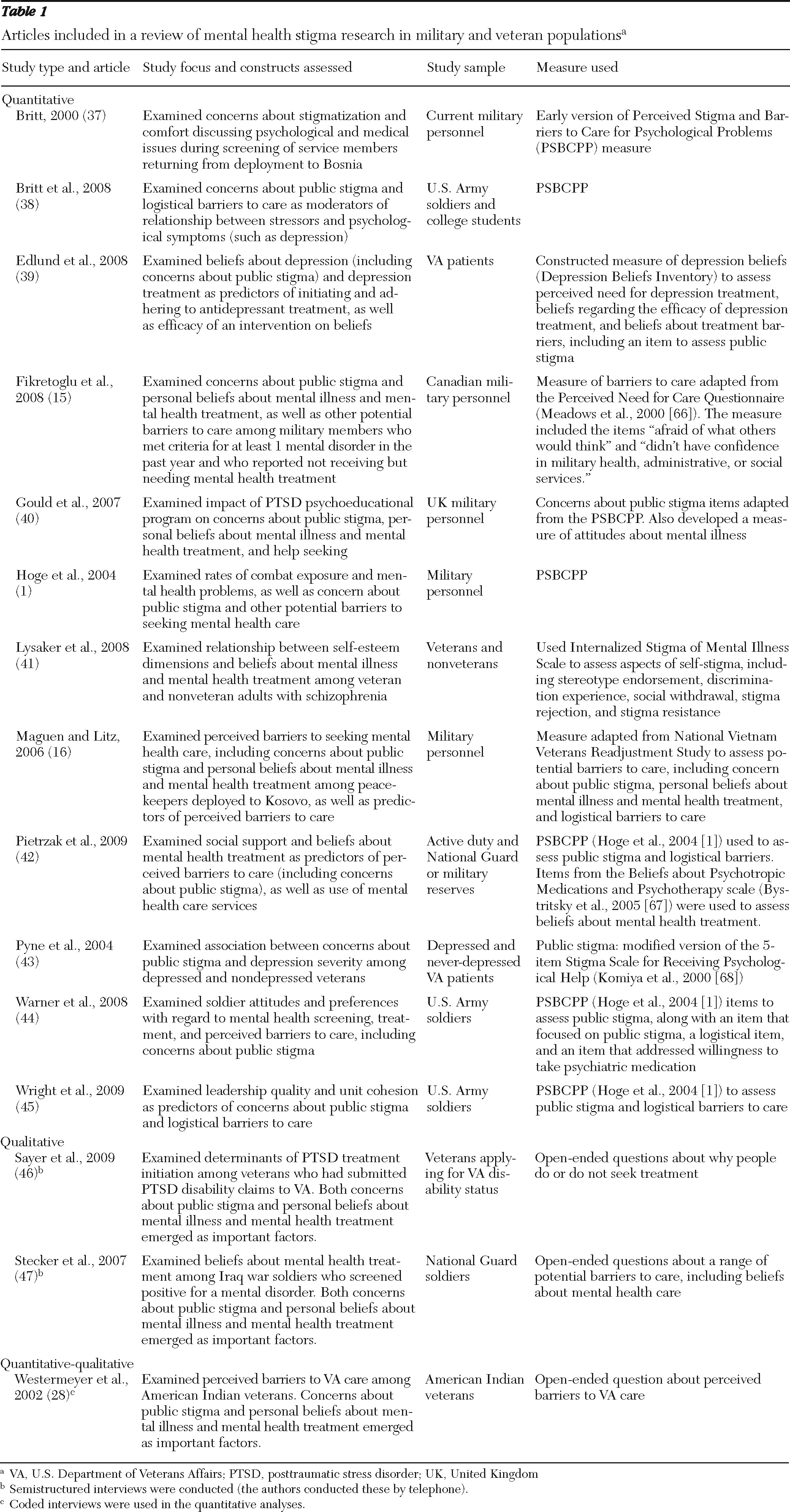

This review revealed only 15 articles that reported empirical data on mental health beliefs about service use (

Table 1). Of these, 12 reported the results of quantitative studies (

1,

15,

16,

37–

45) and three were based on qualitative studies that either focused on mental health-related beliefs or in which mental health-related beliefs emerged as an important issue (

28,

46,

47). All but two of the quantitative studies reported results relevant to concerns about public stigma. In general, results of the literature review appear to support the conclusion that concern about public stigma may be an important barrier to care. For example, almost half of all participants in a study of service members returning from Bosnia indicated that admitting a psychological problem would cause a coworker to maintain distance from the service member (

38), and approximately one in three OEF-OIF veterans who participated in another study reported concern about public stigma associated with seeking mental health care (

1). Similarly, fear of being labeled as having a mental disorder was a concern for 70% of OIF veterans who participated in Stecker and colleagues' (

47) study on barriers to care, and concern about what others would think if one were to seek mental health care was identified as one of the most salient barriers to mental health care among Kosovo peacekeepers (

16).

Fewer studies examined the role of an individual's own beliefs about mental illness and mental health treatment as they relate to service use. As indicated in

Table 1, of the quantitative studies that were included in this review, only two focused primarily on personal beliefs about mental illness and mental health treatment (

39,

41), and many of the studies that did included only one or two items to assess these beliefs. The available studies, however, indicate that these beliefs may be important predictors of service use. For example, Stecker and colleagues (

47) found that discomfort with treatment seeking, as reflected in the belief that one ought to be able to handle mental health problems on one's own, was the most commonly reported barrier to care in a sample of Vietnam and OEF-OIF veterans, and pride in self-reliance was identified as an important deterrent to treatment seeking in a qualitative study of veterans with PTSD (

46). Another study that examined the impact of personal beliefs about mental health treatment on service use in a sample of OEF-OIF veterans found that negative beliefs about the nature of mental health care were significantly related to the use of mental health services (

42).

Overall, the sparse literature that is available appears to support the importance of both concerns about public stigma and personal beliefs about mental health as potential barriers to care for military and veteran populations. However, this literature is characterized by a number of limitations that are described in the section below.

Discussion

Personal beliefs about mental illness and treatment

As noted above, much of the research on mental health-related beliefs in military and veteran populations has focused on concern about public stigma. Studies that have focused on individuals' own beliefs about mental illness and mental health treatment have generally not included a broad assessment of this construct, instead including only a few items for its assessment. Given ample evidence for the importance of personal beliefs about mental health in the general population, this factor warrants additional attention in future research on military and veteran populations. On the basis of a broader review of the literature concerning the general public, and pulling together what have largely been three separate research literatures, three potential domains of beliefs about mental health may be especially relevant here. These domains include beliefs about people with mental health problems (

48–

51), beliefs about mental health treatment (

52,

53), and beliefs about treatment seeking (

6,

54–

56). Efforts to isolate the unique contribution of concerns about public stigma and personal beliefs about mental illness and mental health treatment will make an especially valuable contribution to the literature. The literature review revealed no studies that examined and compared the relative impact of these two factors on mental health service use.

Measurement of mental health beliefs

Most of the studies that were included in this review relied on measures of mental health beliefs that may not adequately reflect the complexity of this construct or that have questionable or undocumented psychometric quality. More specifically, seven of the 12 quantitative studies identified in this literature were based on unvalidated measures developed specifically for the purpose of the study or scales that investigators modified from other measures. This is potentially problematic given that studies that rely on measures of uncertain psychometric quality may produce results that are of questionable validity. Thus additional attention to measurement issues with respect to the assessment of mental health beliefs is encouraged in future research.

Of the 12 quantitative studies that were included in this review, six used the Perceived Stigma and Barriers to Care for Psychological Problems measure or adapted this measure for the particular study purposes. This measure, which includes items that were first introduced in a study by Britt (

37), focuses on public stigma as well as logistical barriers to care. Future research would benefit from supplementing measures of concerns about public stigma like this one with psychometrically sound measures of personal beliefs about mental illness and mental health treatment. For example, researchers interested in assessing beliefs about people with mental illness might consider using the stereotype agreement subscale from the Self-Stigma of Mental Illness Scale (

57). Also useful in this regard might be the Mental Illness Stigma Scale, which was developed to assess attitudes toward people with mental illness (

50).

Mental health beliefs as predictors of service use

Although the assumption that underlies much of the research on mental health beliefs is that concerns about public stigma and negative beliefs about mental illness and mental health treatment serve as deterrents to service utilization, only one of the studies included in this review reported results that specifically addressed the impact of mental health beliefs on use of mental health services (

42). Instead, most studies assessed how commonly mental health beliefs are reported as a barrier to care among those who demonstrate need for care but do not seek out services. Although studies that require participants to identify factors that contribute to their decision not to seek care are certainly useful and informative, what is perceived as a key barrier may not always be what actually predicts use of services. For example, some individuals may not feel comfortable acknowledging, or may not even realize, the role that their own or others' biases about mental illness play in their willingness to seek out mental health care. Thus more direct evidence is needed to confirm the importance of mental health beliefs as a barrier to health care use. Therefore, a primary recommendation based on this review is that researchers examine mental health beliefs as predictors of mental health service use. Further, research in this area would benefit from the application of representations of service use that extend beyond a simple assessment of “use” versus “no use.” For example, it is important to examine the effects of mental health beliefs as they relate to whether one “walks through the door” to seek mental health treatment compared with how they relate to treatment adherence.

Finally, researchers who study the association between mental health beliefs and service use should carefully consider the direction of this association. As noted by Corrigan and Rusch (

7), some people who do not pursue treatment may rationalize this decision in terms of stigma, so that lack of service use predicts mental health beliefs rather than vice versa. In addition, seeking mental health care may lead to an increase in perceptions of stigma, because stigma may become more salient for those who seek care. Prospective designs that attend to the timing of the assessment of attitudes about mental health, the onset of mental health symptoms, and use of mental health services are needed to tease apart the nature of this complex relationship. None of the studies included in this review examined the prospective relationship between mental health beliefs and service use; therefore, this is a key direction for future research efforts.

Other potential barriers to care

Future research will also benefit from careful consideration of the larger context within which the decision to seek or not seek mental health care takes place. The decision to seek mental health care is likely to be influenced by many different factors, and it is important to isolate the unique effects of any given factor by examining it in the context of other explanatory variables. In particular, it will be important to attend to logistical factors that may contribute to service use in studies of military and veteran populations (

58). For example, studies that document the contribution of mental health beliefs to mental health service use above and beyond basic logistical issues, including factors such as availability of needed services and ease of use, will be particularly valuable. A strength of the Perceived Stigma and Barriers to Psychological Problems measure (

37) is that it includes items to assess both concerns about public stigma and logistical barriers to care. Future research that examines the unique effects of these potential barrier categories on service use will provide an important contribution to the literature.

Likewise, studies that consider the role of mental health-related beliefs in the context of institution-specific factors unique to the particular type of health care service under investigation will be especially valuable. For example, in our recent focus groups with OEF-OIF veterans, beliefs about how deserving one is to receive VA health care services, as well as one's perception of fit within the VA health care setting, emerged as important potential predictors of service use (

35). In addition, breaches of confidentiality and documentation of health problems in medical records have been identified as particular concerns for military personnel (

44), given that negative career consequences may result when commanding officers use these medical records to inform decisions about whether a service member is fit to perform specific job responsibilities (

31,

59). Studies that can tease apart the unique effects of these and other potential barriers to care will best inform clinical care and intervention efforts.

Subgroup differences in impact of mental health beliefs on service use

Future research in this area should also attend to the possibility that mental health-related beliefs and their impact on service use may differ across different subgroups of military personnel and veterans (including, for example, women versus men and younger versus older service members). Although several studies presented here examined gender as a predictor of mental health-related beliefs, this review of the literature revealed no studies that explored potential demographic differences in the impact of mental health beliefs on service use. Yet, gender and racial-ethnic differences may be of particular relevance for this relationship (

37). Evidence from the literature on the general population indicates that men and persons from racial-ethnic minority groups receive less health care than women and Caucasians, and both gender and racial-ethnic minority status have been identified as correlates of attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors related to mental health care (

54,

60–

62). For example, there is some evidence that negative attitudes about treatment seeking are more salient among males than females, possibly because masculine gender roles are predicated on a sense of self-reliance and self-control (

33,

34). On the other hand, some findings indicate that concern about public stigma (in this case, family reactions to treatment seeking) is a stronger predictor of service use for women compared with men (

52). Moreover, although few studies have examined joint effects of gender and race-ethnicity on mental health beliefs, a recent study found that concerns about public stigma and mistrust or fear of the mental health system was a particular issue among white males (

9). This finding supports the importance of examining the intersection of race-ethnicity and gender in future studies.

Age is another factor that will be important to consider in future studies of mental health-related beliefs. One recent study from the broader literature found that younger age was associated with more concern about embarrassment with regard to using mental health services, although interestingly, concerns about public stigma predicted treatment discontinuation among older patients but not younger patients (

10).

Conclusions

Empirical knowledge of mental health-related beliefs that serve as barriers to mental health service use is critical to inform ongoing efforts to reduce barriers to care within military and veteran populations. Although the literature examining this topic in the military and veteran populations is sparse, the findings that are available thus far appear to suggest that both concerns about public stigma and personal beliefs about mental illness and mental health treatment may serve as important barriers to service use. As suggested by this review of the literature, there are several important directions for future research. In particular, studies that address personal beliefs about mental illness and mental health treatment, that apply psychometrically sound measures to assess mental health beliefs, and that attend to the broader context within which care-seeking decisions are made can be used to best target resources to engage military personnel and OEF-OIF veterans in health care. Evidence regarding aspects of mental health beliefs that are most relevant to predicting service use can be used to more effectively target interventions. For example, the finding that personal beliefs about mental illness and mental health treatment are stronger predictors of service use than concern about public stigma would suggest a very different intervention strategy than the finding that concern about public stigma is paramount. Likewise, research findings regarding group differences in susceptibility to negative mental health beliefs may be used to inform decisions about which groups are most in need of intervention.

In contrast to many of the factors that have received a great deal of attention in the literature, mental health beliefs represent a potentially modifiable factor and thus hold great promise as a target of future efforts to reduce barriers to care for those who need services most. Drawing from intervention strategies that have been used to combat public and self-stigma in the broader literature, results indicate that both education and contact with the stigmatized group may be promising avenues for intervention (

63,

64). Educational interventions that are targeted to both those experiencing mental health problems and the population more generally may have dual benefits. Specifically, these interventions may reduce personal misconceptions and negative stereotypes about mental health-related issues among those who would benefit from mental health treatment, as well as promote greater acceptance of treatment seeking in the population more generally. In addition, findings indicate that interventions that incorporate contact with individuals who have mental health problems (for example, personal accounts of veterans' experiences with stigma and treatment) may be an especially promising strategy to target negative beliefs about mental illness and mental health treatment (

33,

64,

65).

As this review has revealed, the literature on mental health beliefs as they relate to service use among military personnel and veterans is still in its infancy. Yet this information is critical to identify factors that interfere with the use of mental health services by this population, and where possible, intervene to reduce barriers to care. Thus additional research attention to this important topic is encouraged.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported in part by grant DHI 06-225-2 from the VA Health Sciences Research and Development Service (“Stigma, Gender, and Other Barriers to VHA Use for OEF/OIF Veterans”). Additional support was provided by the National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and the Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiological Research and Information Center (MAVERIC).

The authors report no competing interests.