Permanent supported housing has become a favored approach to housing homeless people with serious mental illness with or without a history of comorbid drug or alcohol addiction. Different opinions exist, however, on best practices for individuals actively using substances (

1–

4). Some recommend that abstinence be required before housing entry or, minimally, during a trial period of residential treatment (

1). This model (termed “linear” or “continuum of care”) requires that participants complete one phase of treatment (achieving abstinence) before proceeding to the next. Proponents of this traditional approach assert that abstinence-contingent housing supports improved substance use outcomes. The uncertainty in offering housing to homeless parents that is not contingent on abstinence or to those using illegal drugs has also been noted (

5). Because mainstream funding sources have provided support with this model, the predominant housing approach remains “linear” (

3).

In contrast, programs using a model loosely referred to as “housing first” (including Pathways to Housing in New York City [

6]) take a “harm reduction” approach where clients are encouraged but not required to reduce substance use before entering housing. Clients are provided elective treatment, with primary emphasis on avoiding adverse consequences of active use rather than on abstinence. The model postulates that stable housing may—in and of itself—motivate reduced substance use (

3), although data supporting this assertion have thus far been limited (

7). No studies have reported specific outcomes for populations of homeless individuals who are actively using substances when provided supported housing that is not contingent on abstinence or treatment.

This observational study examined such outcomes with data from 410 individuals participating in a program for chronically homeless adults who reported either a high frequency of substance use or abstinence. Housing, clinical outcomes, service use, and cost data were compared between individuals actively using substances (when entering supported housing) and those not. Although this study did not include a test of harm reduction interventions compared with programs that require abstinence, it did gather basic information on the potential adverse effects of active substance use at time of housing entry, net of other factors.

Methods

Collaborative Initiative on Chronic Homelessness

The Collaborative Initiative on Chronic Homelessness (CICH) was a multisite federally funded demonstration program begun in 2004 to provide permanent supported housing and supportive primary and mental health services to persons experiencing chronic homelessness (

8). Through a competitive process, 11 communities were selected for funding (

8). They were charged with providing comprehensive health services and linking them to housing and to use of service models that have been proven effective (most notably, intensive case management [

9] or a “housing first” housing model [

6]). Funding was provided by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Health Resources and Services Administration, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).

Study design

The federal agencies sponsoring the initiative invited the VA Northeast Program Evaluation Center to conduct a national evaluation of CICH client outcomes in order to monitor the initiative's implementation and effectiveness (

8). During the 4.5-year data collection period (from February 2004 to September 2008), staff at each site administered assessment interviews to voluntary participants at program entry and quarterly thereafter for up to four years. Because CICH was a service initiative and not a formal research study, there was no systematic inclusion of a comparison group not receiving CICH housing or services (

10).

Sample

Altogether, 756 individuals out of 1,242 program participants (61%) consented to participate in the national program evaluation and were assessed at program entry. Participation was voluntary and did not influence housing placement or other services. Institutional review boards at each participating site approved the informed consent procedures. After complete study description, written informed consent was obtained. Compared with those who did not participate in the national evaluation (N=508, 41%), participants were more likely to be older, male, black, and have medical or mental health problems but were less likely to have substance use problems or be recruited from a community location (streets, parks, or other outdoor areas) (

8). Of the 756 evaluation participants, the study's analytic sample was limited to 410 (54%) participants who were housed within 12 months of program entry and completed an assessment interview just after housing placement and at least one additional follow-up assessment. They reported either high (>15 days of use) or no substance use in the month they were housed. Of 62 assessed but not included in the study, 58 (8%) were never placed into housing and four (<1%) were placed after 12 months. Those never placed did not differ significantly from the study group. [An appendix showing participant selection and comparison of baseline characteristics is available as an online supplement to this article at

ps.psychiatryonline.org.] The remaining sample (N=694) was restricted to high-frequency substance users (N=120, 16%) and abstainers (N=290, 38%) in order to ensure comparison between an actively using and a low-use group. Intermediate-frequency substance users (one to 15 days of use) (N=284, 38%) did not differ significantly from either high-frequency users or abstainers or fell intermediate to each group (see online appendix).

Data collection

Full-time evaluation assistants were trained at project initiation and regularly throughout data collection. Baseline and follow-up interviews were administered in person, and self-report items were recorded during the interview. Interviewer observations and disabling-condition assessments were then confirmed with program staff. Follow-up interviews were typically administered in person or by phone as needed—for example, if participants had relocated. Thus follow-up assessments continued even if participants had discontinued CICH services.

Measures

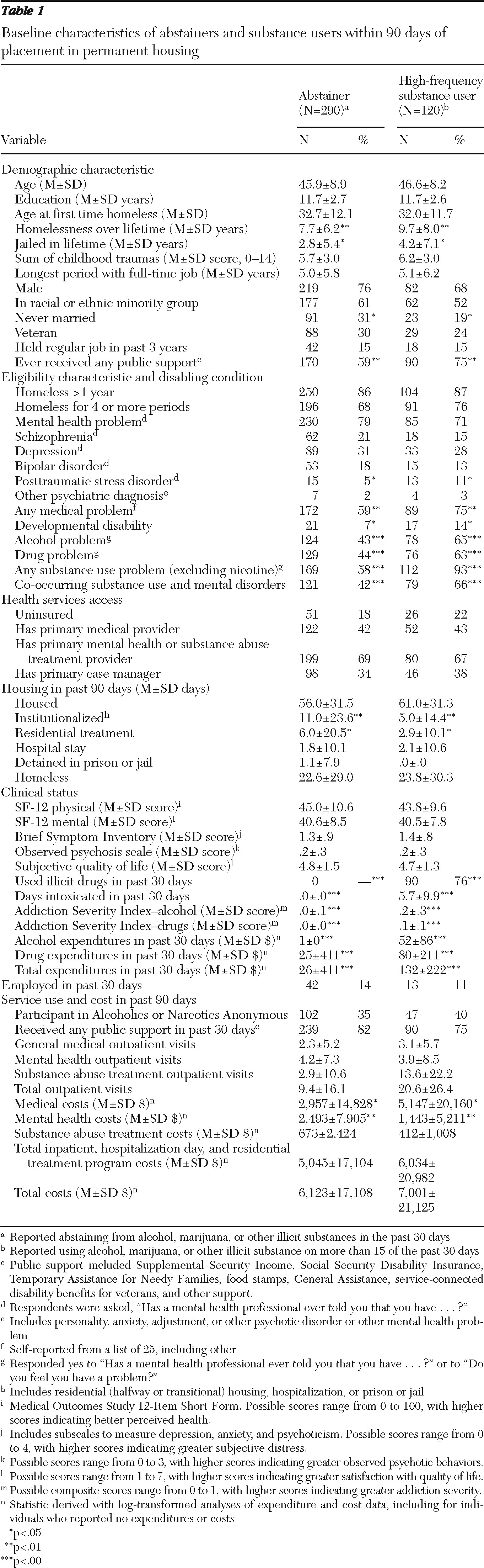

Demographic characteristics, eligibility, disabling conditions, and health service access.

We assessed at screening and confirmed with clinicians sociodemographic characteristics; eligibility characteristics (that is, the current episode of homelessness had lasted a year or longer versus four or more episodes of homelessness during the past three years); and the presence of disabling medical, mental, and substance use conditions. Baseline data were obtained on health insurance, access to a “usual health care provider,” and ability to identify a primary mental health or substance use provider or case manager.

Housing.

Participants were asked the number of days during the previous 90 in which they were housed in each of nine settings. Nights spent in shelters, outdoors, or in vehicles or abandoned buildings qualified as being homeless. Being “institutionalized” included halfway or transitional housing, hospitalization, or detention in prison or in jail. Other categories represented being housed.

Clinical status.

The Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short Form (SF-12) (

11)—a measure including physical and mental health subscales—assessed overall level of functioning in mental and physical domains. Scores range from 0 to 100, with a mean±SD score of 50±10 representing a normal level of functioning in the general population. Higher scores indicate better perceived health. The SF-12 has been validated in homeless populations (

12).

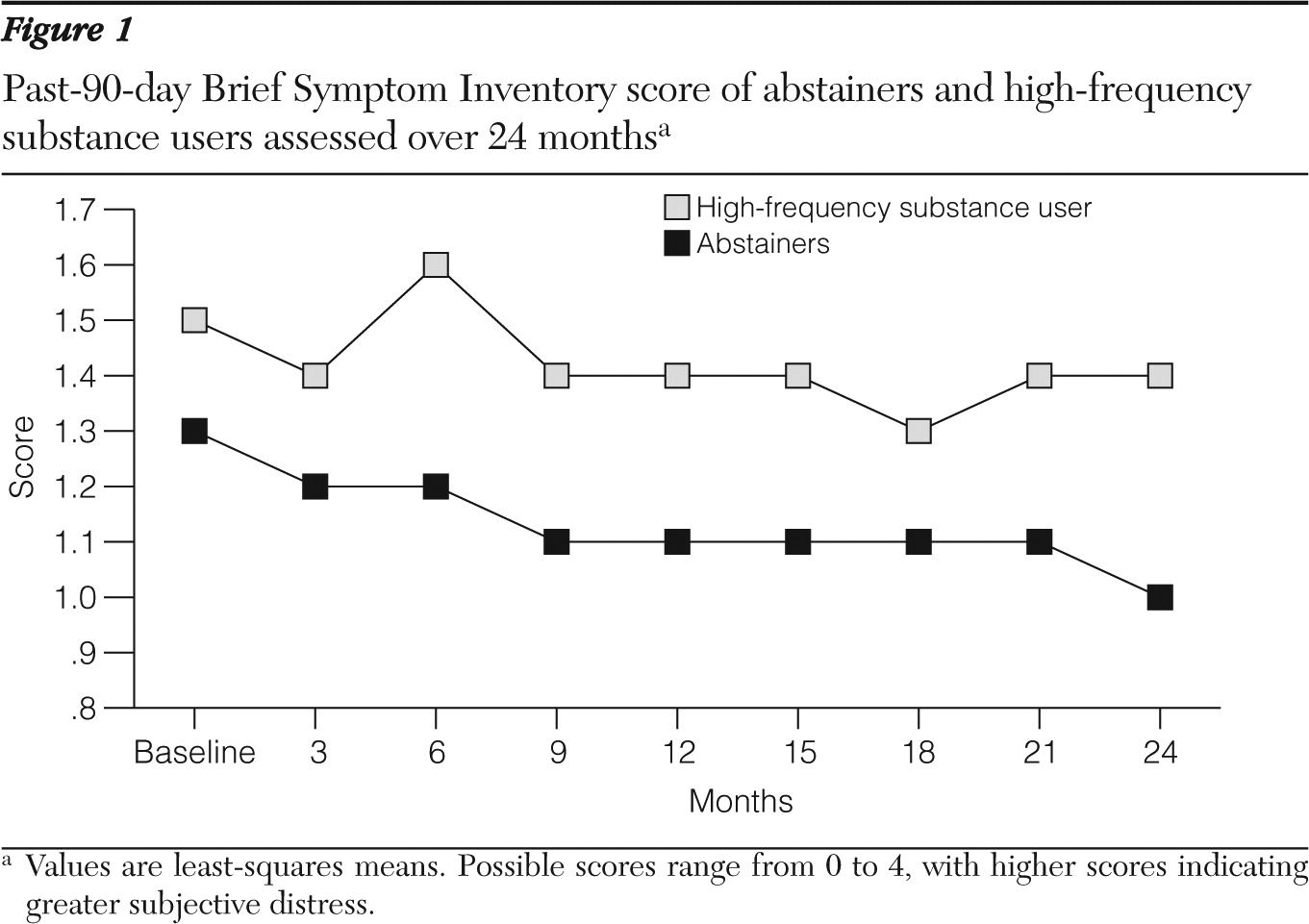

Three subscales of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (

13) were selected for measuring domains of subjective distress—psychoticism, depression, and anxiety. Respondents rated on a scale from 0 (never experience) to 4 (very often experience) 16 items, such as “nervousness or shakiness inside” and “the idea that someone else can control your thoughts.” The BSI score presented here represents the mean value for responses on these three subscales.

An observed psychotic behavior rating scale (

14) included ten psychosis-related symptoms (including hallucinations, delusions, and inappropriate speech) and was rated on the basis of interviewer observations. Each behavior was coded from 0 (not at all) to 3 (a lot). The average score across items constituted the total score.

A participant's subjective quality of life was scored on a standard 7-point scale (from 1, terrible, to 7, delighted), with higher scores indicating greater life satisfaction (

15). Interviewers also documented days employed during the previous 30 days.

The Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (

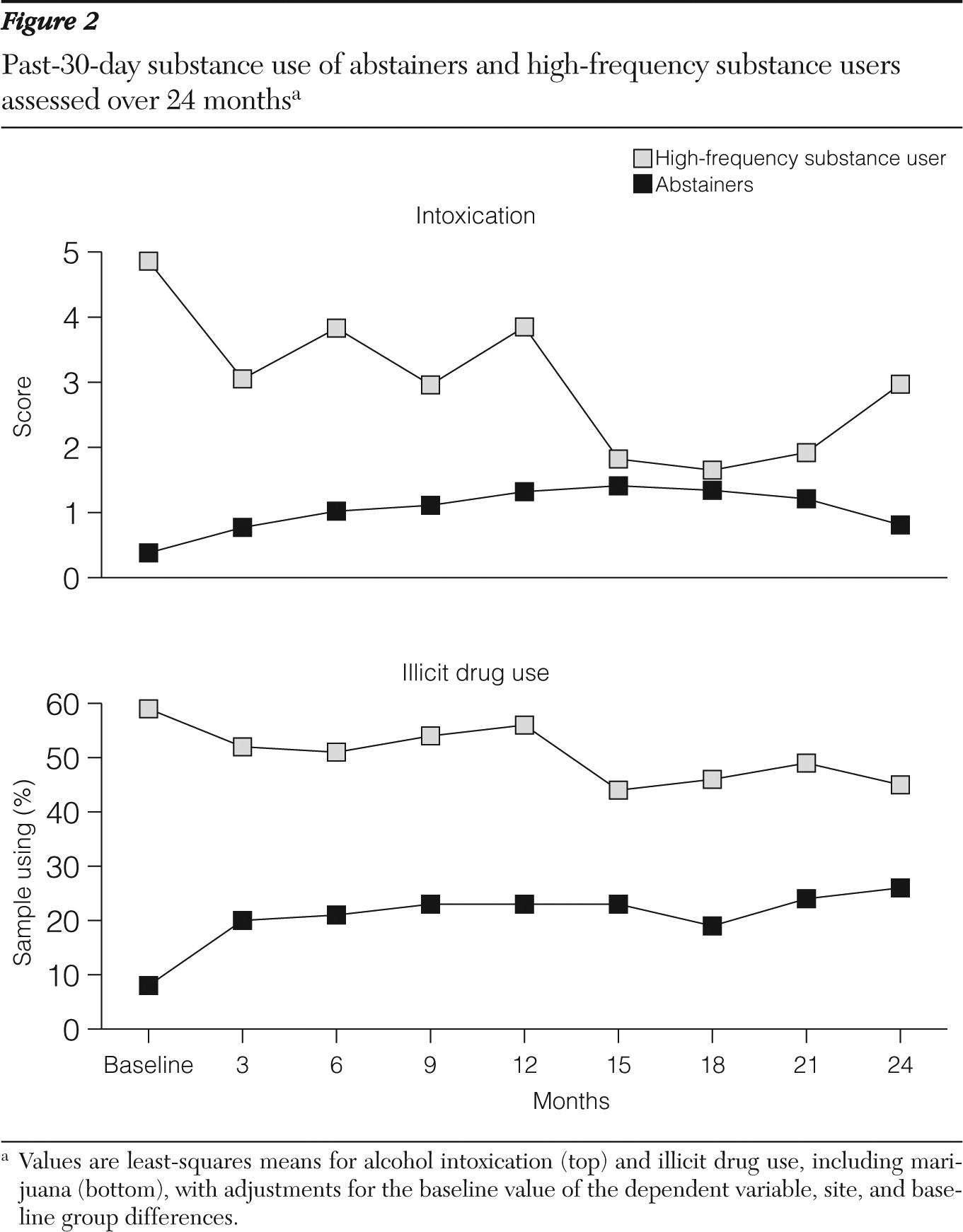

16) documented past-month alcohol and drug use; perceived problems with alcohol use, drug use, or both; and substance-related expenditures. Scoring is based on a seven-item alcohol use subscale (ASI-alcohol) and a 13-item drug use subscale (ASI-drugs). Items are combined in a standard composite score ranging from 0 to 1 for each subscale; higher scores reflect more serious substance use. As part of the ASI, participants reported how many days they drank or used specific types of drugs in the past month and how many days they drank to intoxication.

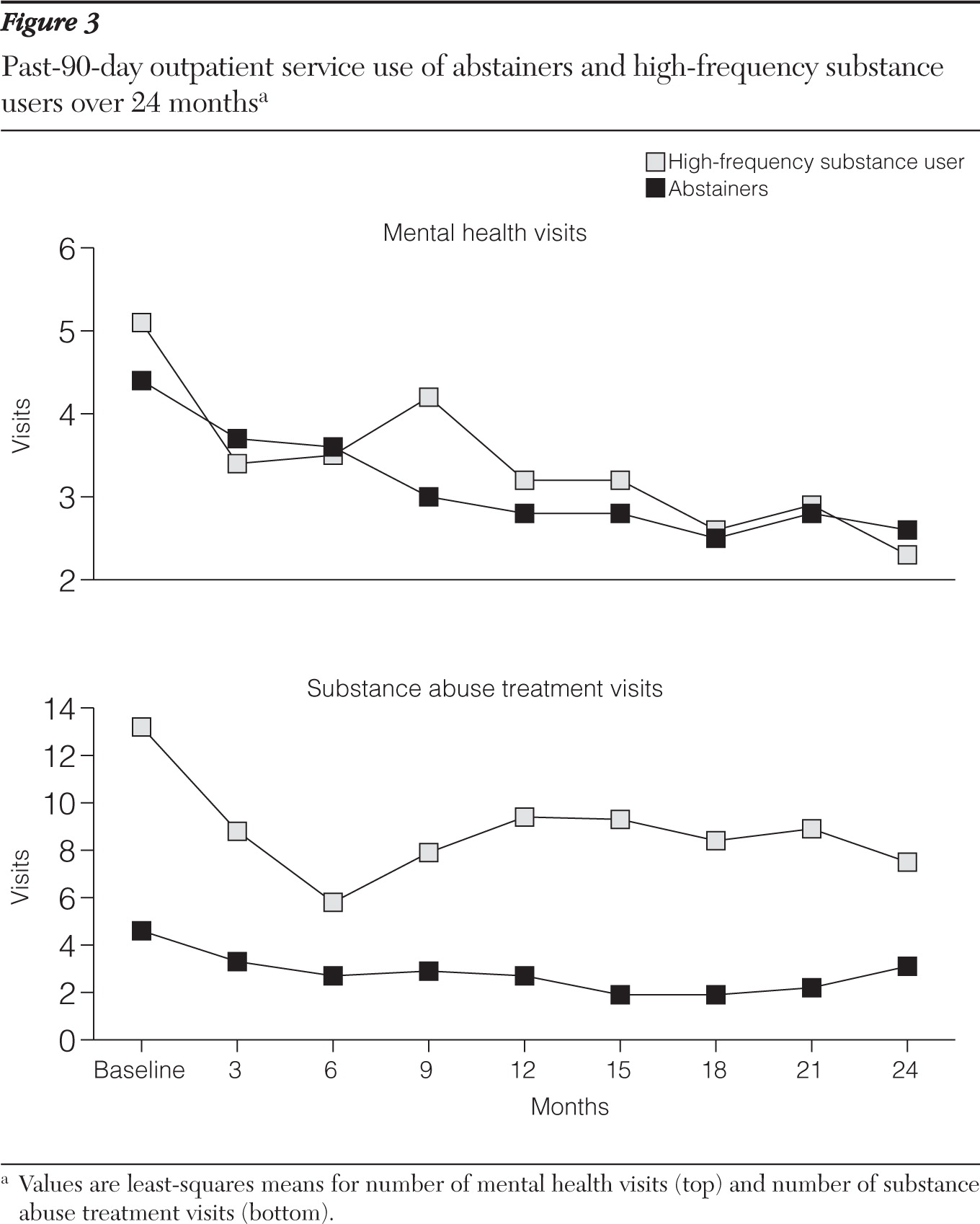

Service use and cost.

Participants reported number and type of general medical and dental, mental health, and substance use treatment visits made during the prior three months. From this information, health service costs were estimated for medical and dental, mental health, and substance use services, and the total for all three service groups. Emergency department, inpatient, and outpatient costs were differentiated within each of the aggregate services. Estimates were computed by multiplying the number of visits or days of care by standard estimates of unit cost for each type of care. Unit costs were estimated with data compiled for a recent cost-effectiveness study of schizophrenia treatment funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (

17). Participants also reported public support received in the past 30 days, including Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), state or local general assistance (GA), food stamps, or VA pension and service-connected disability benefits.

Statistical analysis

Because participant substance use at the precise time of entry into supported housing was not measured, we used data from the ASI (taken during the first assessment after housing entry) to identify high-frequency substance users, defined as those reporting more than 15 days of alcohol, marijuana, or other substance use during the month in which they were housed (N=120, 29%). Abstainers reported no substance use and constituted the comparison group (N=290, 71%).

Because high-frequency and abstinent participants may have differed in ways that could confound outcome comparisons, significant baseline group differences were identified by using chi square and independent-sample t tests. Excepting substance use variables, these differences were included as covariates in outcome comparisons.

Mixed linear regression models were used to test differences between the high-frequency and abstinent groups over time, with controls for the baseline value of the dependent variable, site, and previously identified baseline covariates. The significance of main effects for time, group, and group × time interaction was evaluated. Least-squares means of the outcome measures for each group averaged over all time points were calculated, as were least-squares means at each time point. Cost and expenditure variables were log-transformed to better normalize the data for statistical analysis. All analyses were carried out in SPSS version 16.0 (

18).

No significant group difference in follow-up rates was found. The mean duration of follow-up was 17.9 months, with over 50% of participants actively participating in the evaluation two years after baseline.

Discussion

This study addressed an emerging question in the debate surrounding services for chronically homeless people: can active users of substances be housed successfully via a low-demand housing model? Prior studies have demonstrated success in housing disabled individuals with and without a history of substance use problems (

3) and individuals with severe alcohol dependence (

7) when compared with generally available housing and treatment services. This study is, to our knowledge, the first evaluation of housing and clinical outcomes comparing individuals with and without active drug or alcohol use at the time of housing entry in which both groups had access to full-service supportive housing. In short, our results show equal two-year success in housing high-frequency users and abstainers. This finding is hopeful for policy makers and advocates whose primary goal is to house the homeless population and suggests that requiring abstinence is not necessary for successful independent housing outcomes. It does not, however, address whether substance use or other clinical outcomes would be different with required abstinence.

Also promising, and consistent with a growing literature, is the finding that health service costs diminish when individuals are stably housed, although in the absence of a control group this cannot be causally attributed to treatment (

7,

19).

Generally, alcohol and drug use patterns showed some limited positive change over time when high-frequency users were stably housed. This finding may lend support to the hypothesis that housing alone may motivate reduced substance use (

3). However, caution is warranted given high rates of past-30-day drug use and days intoxicated throughout follow-up. To be explicit, stable housing is not substance use treatment. Use or availability of evidence-based substance use treatments among study participants is not known but could improve these outcomes.

Moreover, the abstainers increased illicit drug use over time. Although this result might be expected given addiction's chronic nature, it raises questions about whether abstinence-contingent housing might mitigate this finding and be useful for subgroups of homeless persons. Indeed, as noted by Kertesz and colleagues (

4) and others (

20), the relevant policy question should perhaps be not “what works?” but “what works for whom?”

Also of potential concern is our finding that high-frequency users had poorer mental health status scores and subjective quality of life than abstainers. BSI scores showed improvement among the abstainers. No such positive change was seen among the high-frequency users, although there was no evident deterioration. These results deserve attention, particularly given effective evidenced-based treatments for substance dependence that may simultaneously benefit mental health outcomes.

Several limitations bear on the interpretation of these results. First, the CICH project was not an experimental research study, and there may be additional unmeasured differences between groups (such as antisocial personality or drug craving) that confounded our analysis. Although it seems unlikely that such characteristics would artificially increase housing success among high-frequency users, they may offer an explanation for poorer mental health and substance use outcomes. Although our results are primarily descriptive, we used multiple-regression mixed models to adjust for all measured, potentially confounding factors.

Second, there were no formal structured diagnostic assessments or toxicology assessments of substance use. There may have been underreporting of substance use by either group. Limiting the analysis to groups at either extreme of substance use, however, reduced the likelihood that the groups were not actually different. Third, with design and real-world constraints, we relied heavily on self-report for housing and clinical outcomes, as is typical in homelessness services research (

3,

7). Fourth, we examined multiple outcomes with liberal use of the .05 alpha criterion, thereby increasing risk of spurious findings and suggesting even fewer significant group differences.

Finally, there remains uncertainty about generalizability. The high-frequency users identified at CICH sites who agreed to participate in the national evaluation, despite their heavy substance use, may have been more motivated to remain housed than other groups of substance-using individuals. Indeed, individuals not participating in the national evaluation were more likely to have substance use problems and be recruited from streets, parks, and other outdoor sites than evaluation participants, potentially indicating greater addiction severity and overall poorer functioning. In addition, CICH sites were competitively selected for funding and may represent best-case scenarios for implementation of supported housing and retention. Nonetheless, by setting such high thresholds for inclusion into the high-frequency use group, our findings suggest that high levels of substance use, including nonmarijuana illicit drug use, provide little to no interference with housing outcomes among voluntary participants in real-world supported community housing programs.