Per capita mental health spending in the United States was relatively stable between 1996 and 2000 (

1). However, between 2000 and 2006, per capita spending increased from $104.25 to $148.56, which Frank and colleagues (

1) attributed to the increased use of prescription drugs. They also found that spending on mental health varied considerably by payer. In Medicaid, mental health spending grew more slowly than spending for overall health care, whereas in private insurance the opposite was true: growth in mental health spending outpaced overall spending.

Frank and colleagues (

1) did not include the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) in their analyses, and there are a number of features that make VA an interesting case study. First, VA is one of the nation's largest integrated health care providers, with 153 medical centers, 232 vet centers, more than 800 community-based outpatient clinics, and 135 nursing homes (

2), and veterans can access a wide range of services for mental health and substance use disorders. Second, the benefits are generous, and approximately two-thirds of veterans who use the VA each year receive free services because they have a service-connected disability or have passed an income-based means test. Thus the majority of veterans do not face financial barriers to care, and the VA has become an essential part of the safety net (

3). Third, the VA does not use carve-outs, which are frequently used by insurers to manage mental health spending (

1). Instead, all providers are employees of the VA, and they provide care in VA facilities. Finally, the VA has to provide these services within a capitated global annual budget set by the U.S. Congress.

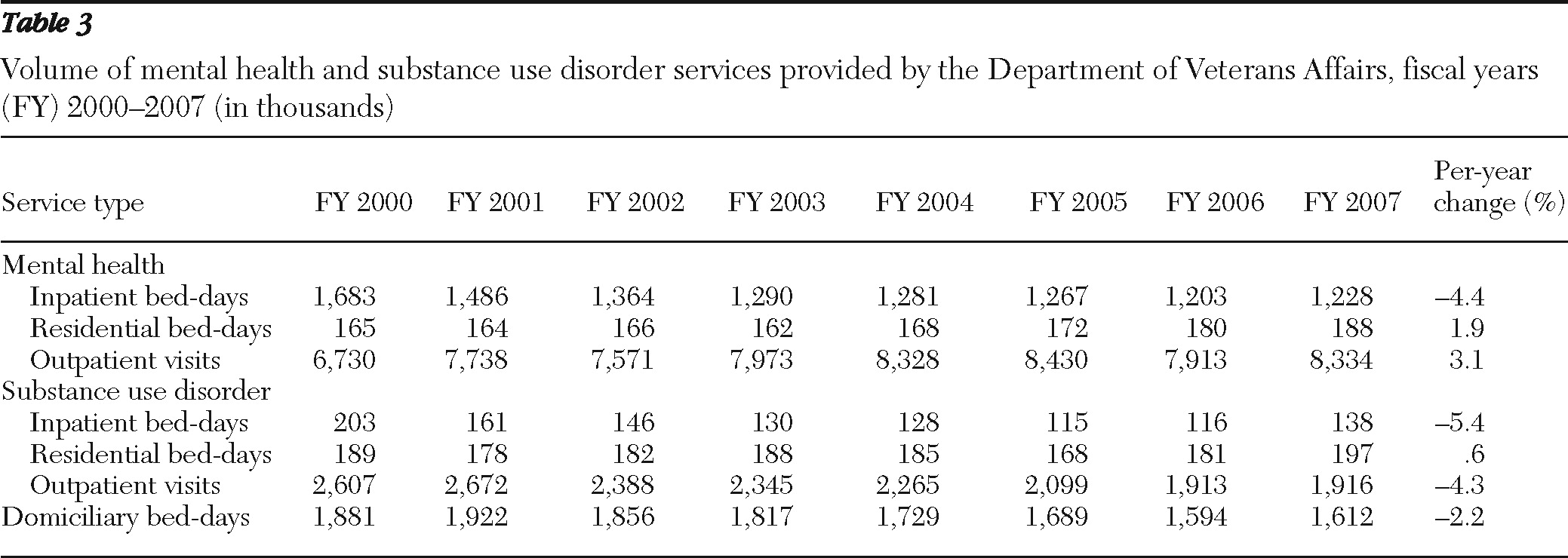

Several studies have analyzed VA spending on treatment for mental health and substance use disorders since the mid-1990s, when the VA was reorganized into Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) that focused on access and primary care. In just four years, the VA was transformed from a system of hospitals providing inpatient care to an expanded system of hospitals and clinics emphasizing outpatient services, with no adverse effect on mortality (

4). In mental health, the use of inpatient care declined dramatically, from 3.5 million bed-days in 1995 to 1.5 million bed-days in 2001. In turn, outpatient care increased, as did mental health pharmacy spending (

5). The effects were similar, if not larger, for substance use disorder treatment. Inpatient spending for substance use disorder treatment declined from $442 million in 1993 to $86 million in 1999 (1999 dollars) (

6). Spending for outpatient treatment of substance use disorders increased but at a slower pace than the cuts to inpatient spending, such that the net effect was a decline in the average per capita amount spent on substance use disorder treatment from $221 to $103 over this seven-year period. Some inpatient wards were converted to outpatient clinics or to psychosocial residential care programs. These residential programs grew rapidly after 1995 (

5), and they enabled the VA to provide mental health and substance use disorder care to more veterans without increasing total costs (

7).

Since 2001, little information has been reported on VA mental health and substance use disorder spending, a period for which Frank and colleagues (

1) reported the largest growth in mental health spending per capita in the non-VA population. There has also been considerable discussion about the mental health of soldiers deployed to Operation Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF-OIF) (

8,

9). Early evidence suggests that a quarter of returning soldiers have a mental disorder diagnosis and that approximately half of those with any diagnosis have more than one (

10). Common diagnoses include posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders (

10,

11).

In this article, we describe VA spending on mental health and substance use disorder treatment for fiscal years (FYs) 2000 through 2007—a period during which the VA had a large increase in users.

Methods

The VA collects cost and service utilization data in several large systemwide databases. Previously the VA used the VA Cost Distribution Report (CDR) for financial accounting (

5,

6). In the late 1990s, the VA replaced the CDR with a new activity-based accounting system, the Decision Support System (DSS), and then stopped producing the CDR. In this study, we summarized the DSS inpatient and outpatient utilization data along with the outpatient pharmacy data to estimate spending per fiscal year. We identified mental health and substance use disorder care by using the outpatient clinic stop and the inpatient “treating specialty,” which are described in more detail elsewhere (

12–

14). A table of the specific clinic codes is available upon request. It should be noted that mental health treatment that is provided outside specialty mental health clinics—for example, in primary care—is not captured in these analyses.

We tabulated total costs, service utilization, and cost per VA user for FYs 2000–2007. The data give a complete picture of care provided by the VA. Because some care is provided in the community under contract and paid for by the VA, we tabulated these contract costs from the VA Fee Basis files, according to the year that the funding was disbursed. We did not include service utilization from the Fee Basis files because it was less clear when the care was provided. This means that total costs are accurate but that the reports of the volume of care are underestimated. We report expenditures in 2007 dollars and inflate expenditures for prior years using the general consumer price index report (

15). We also report total outpatient pharmacy costs, and in a subanalysis using Smith and Chen's (

16) methods, we identified costs related to common classes of psychiatric drugs: antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics and sedatives-hypnotics, and lithium (a list of the VA drug classes is available upon request).

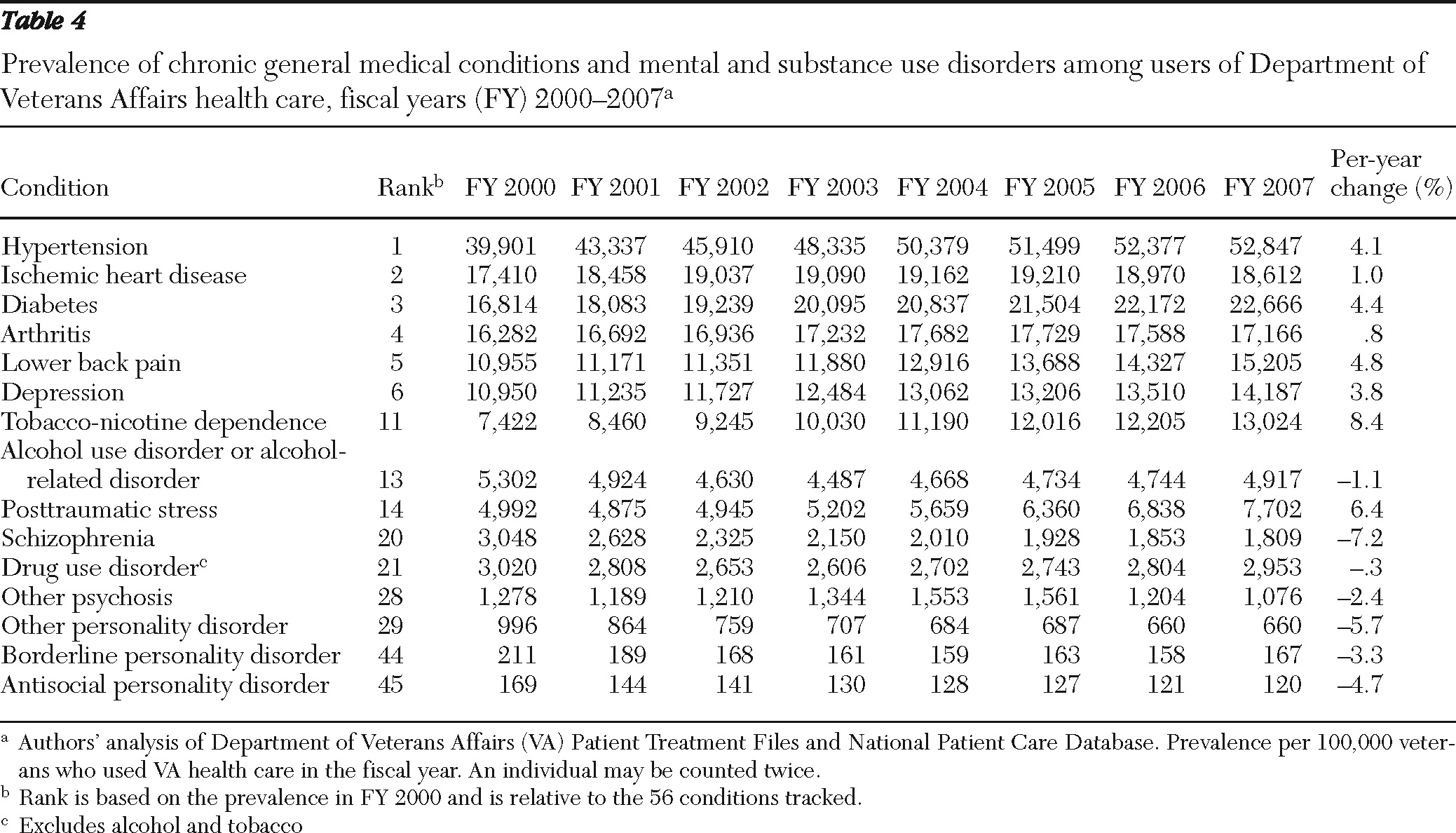

Comparing spending across years implicitly assumes that patient case mix is stable. To test this assumption, we tabulated the prevalence of 56 chronic illnesses for each year of data using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's Clinical Classification Software that was modified for the VA (

17–

19). We standardized the prevalence per 100,000 VA users. All research activities were approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board.

Discussion

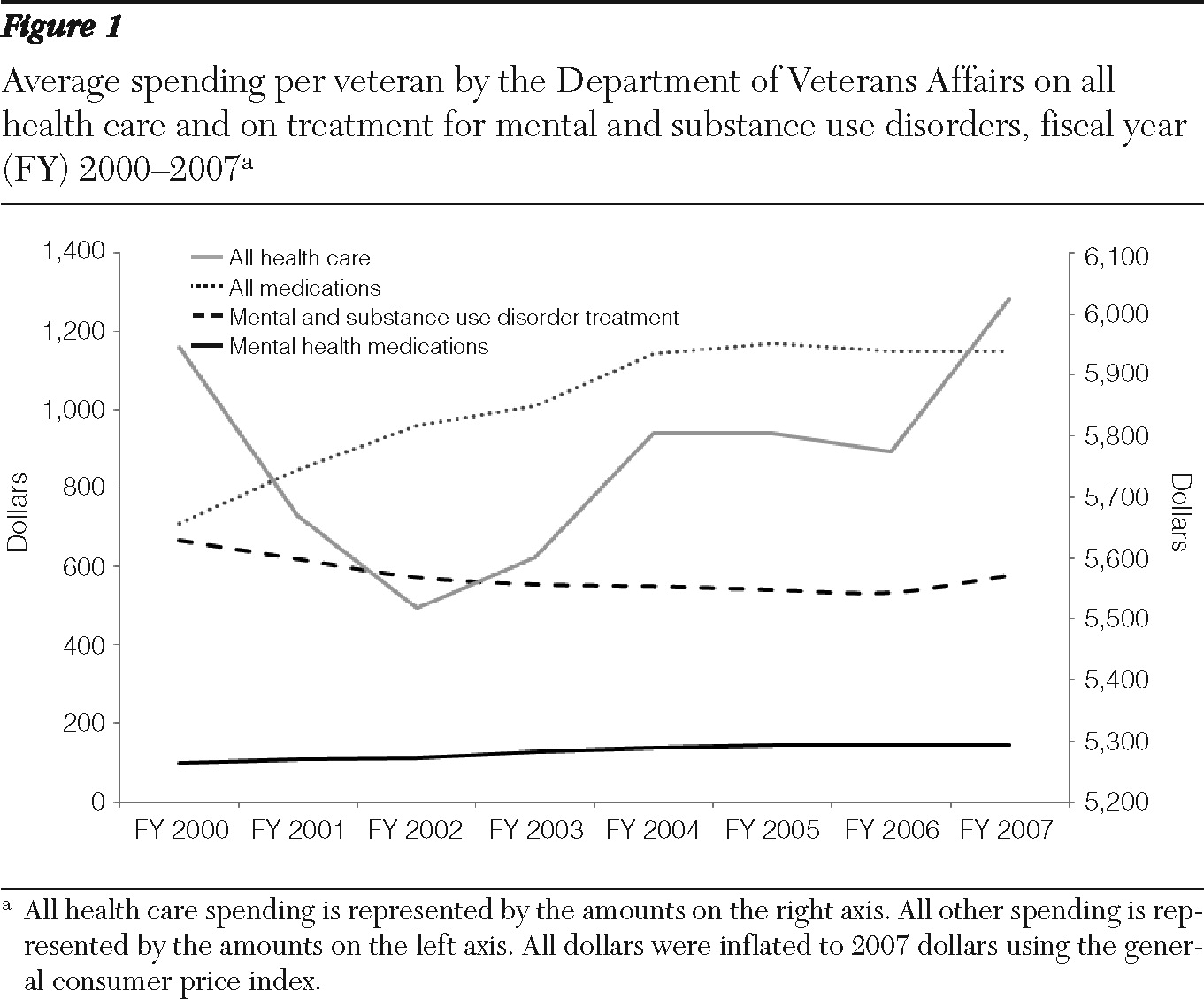

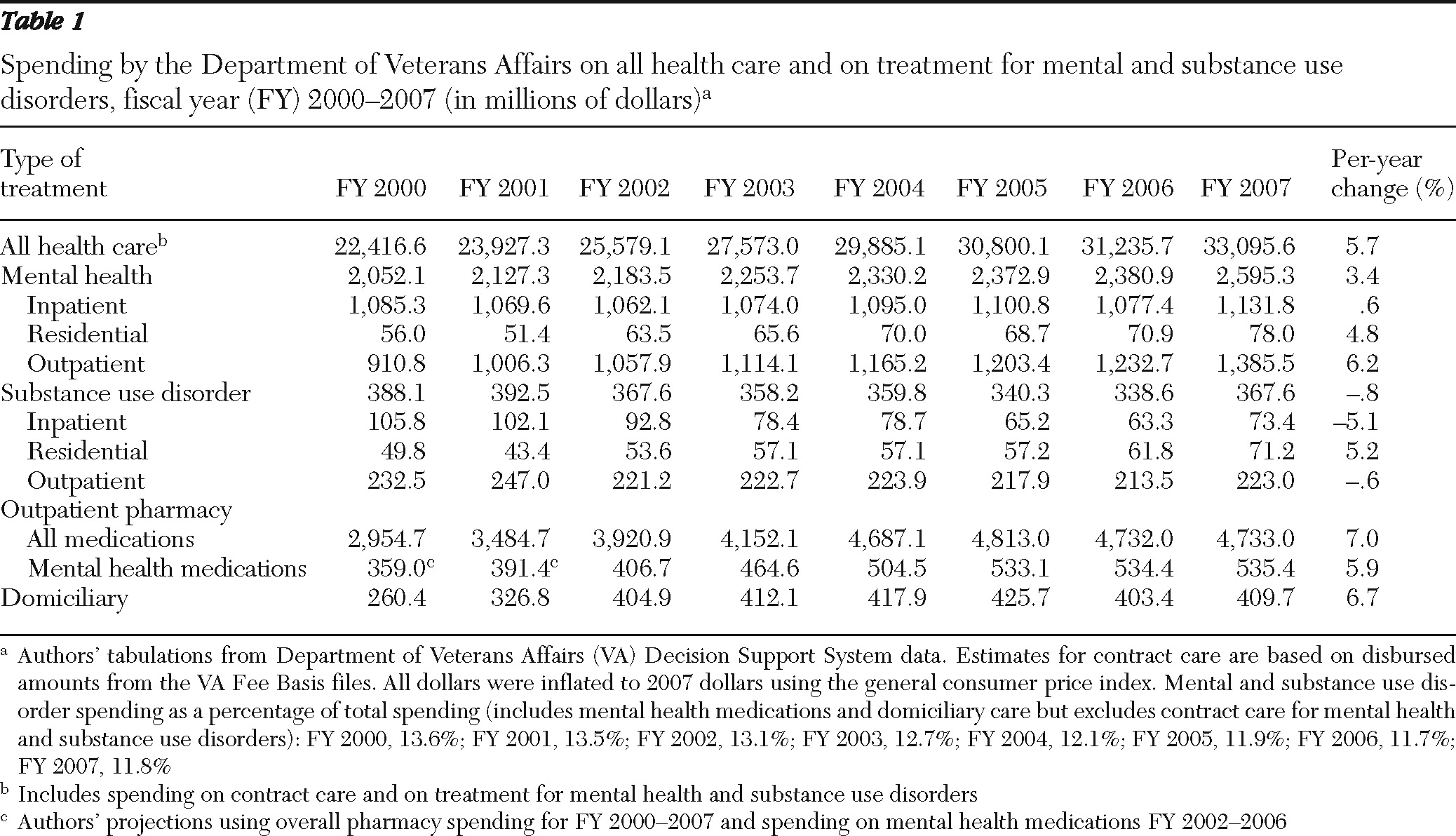

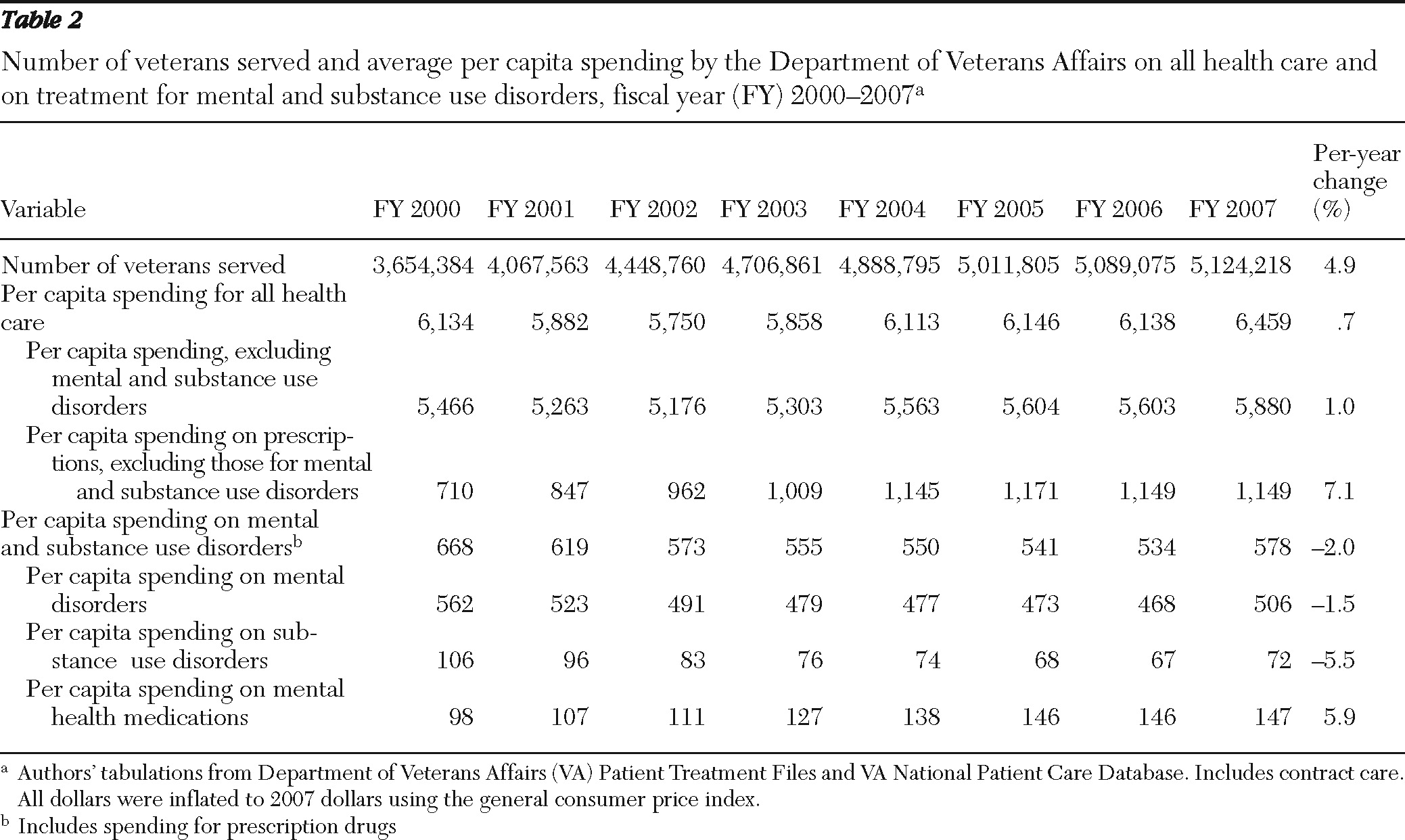

The number of veterans who used VA health care grew 40.2%, from 3.65 million in FY 2000 to 5.12 million in FY 2007 (4.9% per year), and overall spending increased 5.7% per year, but average total health care spending per veteran increased only .7% per year. These findings are considerably lower than national per capita annual growth estimates from Catlin and colleagues (

20), which were greater than 5% per person for the same time period.

Mental health and substance use disorder spending by the VA did not keep pace with overall health care spending. This is most evident in the average per capita spending, which decreased from $668 in FY 2000 to $534 in FY 2006. FY 2007 bucked the trends in prior years with 8.1% and 8.6% increases in mental health and substance use disorder spending, respectively. These increases may be a result of the large proportion of veterans with mental health needs returning from OEF-OIF (

10,

21,

22), because the number of veterans with depression and PTSD grew substantially over this time. These changes could also be responses to the Uniform Mental Health Services Act, which was enacted in 2006 to ensure that all veterans, regardless of where they receive care, have access to mental health services (including substance use disorder treatment) at VA hospitals and community-based outpatient clinics. According to internal VA data, full-time-equivalent mental health staff grew by 8% from 2005 to 2007; the growth was led by therapists (26% increase), followed by social workers (21%), psychologists (13%), physicians (5%), and nurses (<1%). We could not identify staffing data before 2005 to determine whether the staffing was relatively stable in the earlier years. Finally, costs may have increased in response to changes in the regional distribution of the veteran population or in provider efficiency, but such analyses were beyond the scope of this study.

The VA's mental health spending resembles Medicaid's spending as reported by Frank and colleagues (

1). While private insurers experienced overall increases in spending on prescription drugs, Medicaid and VA saw smaller increases in spending for prescription drugs for mental health conditions. In the VA, spending on pharmaceuticals, both overall and for mental health medications, increased between FY 2000 and FY 2004 and then leveled off. It is not clear what caused this leveling off. One explanation is that the demand may have changed for Medicare-eligible veterans with the implementation of Medicare Part D in January 2006, but this would not explain why VA prescription spending slowed between FY 2004 and FY 2005. Demand could also reflect changes in the case mix of veterans with mental health conditions. The prevalence of schizophrenia decreased from 3,048 (per 100,000 veteran users) in FY 2000 to 1,809 in FY 2007 (an average decrease of 7.2% per year). In contrast, the prevalence of depression, which is less complex to manage, grew 3.8% per year from 10,950 (per 100,000 Veteran users) to 14,187, not including care provided in primary care clinics for patients with depression. However, the changes in case mix seem an unlikely explanation, because further examination shows that the prevalence of schizophrenia decreased more rapidly between FY 2000 and FY 2004, when drug spending was increasing.

A third explanation is that this leveling off could reflect the VA's ability to manage care. The VA uses a national formulary and encourages use of generics when possible. The VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Services provides guidance for managing depression and for using second-generation antipsychotics for schizophrenia. In the latter case, the physician is encouraged to identify an effective therapy for the patient, and if there is more than one equivalent option, the physician is directed to consider the less expensive agent. It is not clear whether clinicians use these recommendations when prescribing second-generation antipsychotics for patients with schizophrenia or in situations outside of the document's primary aim (for example, in treating depression). Although a number of generic medications became available around the time that spending leveled off (for example, citalopram), other common medications (for example, fluoxetine) were available as generics in earlier years, when the spending was increasing more rapidly. Therefore, with the data presented here, we do not have an explanation for why spending grew rapidly from FY 2000 and then leveled off. Further research would be needed to isolate the likely mechanisms.

This study has a number of important limitations. The VA, like other health care systems, is increasingly relying on primary care providers to offer a broad portfolio of services. Our data show the cost and services provided in specialized mental health clinics. This report also highlights the cost of drugs commonly used in psychiatric outpatient care, but the data do not include any health care services provided in primary care or general medical clinics. For example, if a veteran talked to his or her primary care doctor about a mental health concern or side effects related to a mental health medication that did not translate into a new prescription, then these consultations would be missing from our cost estimates. The spending estimates for mental health medications are also imperfect because we excluded some mental health drugs that are frequently used in non-mental health indications. Therefore, the figures for mental health spending, per se, should be viewed as conservative estimates.

Although it might be tempting to suggest, for the same reasons, that our estimates are conservative with regard to substance use disorder treatment (that is, an underestimation of the amount of substance use disorder services provided in the VA), recent research has shown that VA primary care providers are not providing substance use disorder services (

23). Thus, as the nation's largest provider of substance use disorder treatment, this contraction could indicate that fewer veterans with a substance use disorder are seeking care in the VA or that more veterans are paying out of pocket, are looking to other insurers to cover their costs, or are not getting needed care. Using data from 2003 and 2004, Petersen and colleagues (

24) found that 80% of veterans under age 65 relied on VA for mental health and substance use disorder care; reliance on VA decreased to 55% for veterans over age 65 because of Medicare. Unfortunately, there are no data from more recent years to determine whether veterans are becoming more or less reliant on VA services.

One trend worth following is VA's payments to community providers (that is, contract care). Between FY 2000 and FY 2007, spending on contract care grew rapidly at 18.3% per year. Although such growth is likely to improve access to care for veterans who live in rural areas, it is not clear how providers are managing care across multiple systems, especially when most providers do not use an electronic medical record (

25,

26). A recent study found that contract care was frequently used for emergency care or treatment that requires recurrent visits to a clinic (for example, dialysis and physical rehabilitation) (

27), while veterans received most (88%) of their outpatient psychiatric care and almost all of their alcohol and drug treatment at VA facilities. Use of contract providers could also have implications for outcomes, but like Frank and colleagues (

1), we have not linked the spending data to outcomes. Therefore, we cannot make statements about whether the additional (or decreased) spending was associated with marginal benefits.