Review of Research Evidence Supporting Guideline Statements

Assessment and Determination of Treatment Plan

Statement 1 – Initial Assessment

Grading of the Overall Supporting Body of Research Evidence for Assessment of a Patient with Possible Borderline Personality Disorder

Statement 2 – Quantitative Measures

Grading of the Overall Supporting Body of Research Evidence for Use of Quantitative Measures

Statement 3 – Treatment Planning

Grading of the Overall Supporting Body of Research Evidence for Evidence-Based Treatment Planning

Statement 4 – Discussion of Diagnosis and Treatment

Psychoeducation Versus Wait-List

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with wait-list | Difference in effect with psychoeducation |

Severity of BPD | |||||

Assessed with ZAN-BPD Follow-up: mean 12 weeks | 130 (two RCTs: Zanarini and Frankenburg 2008; Zanarini et al. 2018) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 9.16 | Mean 1.33 lower (ns) |

Anxiety | |||||

Assessed with CUXOS Follow-up: mean 12 weeks | 80 (one RCT: Zanarini et al. 2018) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWb for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 40.11 | Mean 4.96 lower (ns) |

Depression | |||||

Assessed with CUDOS Follow-up: mean 12 weeks | 80 (one RCT: Zanarini et al. 2018) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWb for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 26.89 | Mean 6.11 lower (ns) |

Functioning | |||||

Assessed with SDS Follow-up: mean 12 weeks | 80 (one RCT: Zanarini et al. 2018) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWb for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 9.76 | Mean 2.18 higher (ns) |

Severity of Borderline Personality Disorder

Severity of Symptoms Associated With Borderline Personality Disorder

Global Impression and Functioning

Incidence of Adverse Events, Serious Adverse Events, and Withdrawal Due to Adverse Events

Grading of the Overall Supporting Body of Research Evidence for Psychoeducation in Patients With BPD

Psychosocial Interventions

Statement 5 – Psychotherapy

Interpersonal Psychotherapy Versus Wait-List Plus Clinical Management

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with wait-list plus clinical management | Difference in effect with IPT |

Severity of BPD | |||||

Assessed with BPDSI Follow-up: mean 10 months | 43 (one RCT: Bozzatello and Bellino 2020) | ⨁⨁◯◯ LOWa for greater effects with IPT | – | Mean score at endpoint = 36.1 | Mean 8.4 lower (P= 0.01) |

Severity of BPD symptoms | |||||

Assessed with BIS-11 and SHI Follow-up: mean 10 months | 43 (one RCT: Bozzatello and Bellino 2020) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWb for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint on BIS-11 = 64.8, on SHI = 6.91 | Mean 12.6 lower on BIS-11 (P= 0.03) and 2.8 higher on SHI (P= 0.27) |

Functioning | |||||

Assessed with CGI-S and SOFAS Follow-up: mean 10 months | 43 (one RCT: Bozzatello and Bellino 2020) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa for greater effects with IPT | – | Mean score at endpoint on CGI-S = 3.1, on SOFAS = 57.1 | Mean 1.0 lower on CGI-S (P= 0.009) and 11.1 higher on SOFAS (P= 0.02) |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Versus Treatment as Usual

Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with TAU | Difference in effect with ACT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Severity of BPD | |||||

Assessed with BEST Follow-up: mean 13 weeks | 41 (one RCT: Morton et al. 2012) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa for greater effect with ACT | – | Mean score at endpoint = 47.4 | Mean 17.2 lower (P= 0.028) |

Anxiety | |||||

Assessed with DASS Follow-up: mean 12 days | 41 (one RCT: Morton et al. 2012) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa for greater effect with ACT | – | Mean score at endpoint = 26.3 | Mean 11.6 lower (P= 0.025) |

Depression | |||||

Assessed with DASS Follow-up: mean 13 weeks | 41 (one RCT: Morton et al. 2012) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa for greater effect with ACT | – | Mean score at endpoint = 31.0 | Mean 15 lower (ns) |

Difficulties in emotion regulation | |||||

Assessed with DERS Follow-up: mean 13 weeks | 41 (one RCT: Morton et al. 2012) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa for greater effect with ACT | – | Mean score at endpoint = 140.0 | Mean 35.3 lower (P= 0.008) |

Hopelessness | |||||

Assessed with BHS Follow-up: mean 13 weeks | 41 (one RCT: Morton et al. 2012) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa for greater effect with ACT | – | Mean score at endpoint = 16.4 | Mean 8.9 lower (P= 0.006) |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Manual-Assisted Cognitive Therapy Versus Treatment as Usual

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with TAU | Difference in effect with MACT |

Deliberate self-harm | |||||

Assessed with deliberate self-harm frequency (scale NR) Follow-up: mean 6 months | 30 (one RCT: Weinberg et al. 2006) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa for greater effects with MACT | – | Mean at endpoint for frequency = 6.69 | Mean 4.71 lower (P< 0.001) |

Assessed with deliberate self-harm severity (scale NR) Follow-up: mean 6 months | 30 (one RCT: Weinberg et al. 2006) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa for greater effects with MACT | – | Mean severity score at endpoint = 1.01 | Mean 0.5 lower (P< 0.001) |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Versus Treatment as Usual

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with TAU | Difference in effect with CBT |

Anxiety | |||||

Assessed with STAI Follow-up: mean 24 months | 102 (one RCT: Davidson et al. 2006) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa for greater effect with CBT | – | Mean score at endpoint = 50.9 | Mean 7.96 lower (0 to 0) |

Depression | |||||

Assessed with BDI Follow-up: mean 24 months | 102 (one RCT: Davidson et al. 2006) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 28.8 | Mean 2.3 lower (0 to 0) |

Proportion of participants with suicidal acts | |||||

Follow-up: mean 24 months | 102 (one RCT: Davidson et al. 2006) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWb for similar risks | OR 0.78 (0.30–1.98) | 531 per 1,000 | 62 fewer per 1,000 (277 fewer to 161 more) |

Mean number of suicidal acts | |||||

Follow-up: mean 24 months | 102 (one RCT: Davidson et al. 2006) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWb for greater effect with CBT | – | Mean number at endpoint = 1.73 | Mean 0.91 lower (1.67 lower to 0.15 lower) |

Quality of life | |||||

Assessed with EQ-5D Follow-up: mean 24 months | 102 (one RCT: Davidson et al. 2006) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 0.66 | Mean 0.02 lower (0 to 0) |

Social functioning | |||||

Assessed with SFQ Follow-up: mean 24 months | 102 (one RCT: Davidson et al. 2006) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 12.3 | Mean 0.7 lower (0 to 0) |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Dialectical Behavior Therapy Versus Treatment as Usual

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with TAU | Difference in effect with DBT |

Severity of BPD | |||||

Assessed with BSC-23 Follow-up: mean 32 weeks | 125 (one RCT, one observational study: Gregory and Sachdeva 2016; McMain et al. 2017) | ⨁⨁◯◯ LOWa for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 45.99* | Mean 4.91 higher (ns) |

Anger, depression | |||||

Assessed with various scales Follow-up: 3–12 months | 227 (one RCT, one nRCT, one observational study: Bohus et al. 2004; Feigenbaum et al. 2012; Gregory and Sachdeva 2016; McMain et al. 2017) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b,c,d for similar effects | – | Inconsistent effects with TAU | Inconsistent |

Dissociative experiences | |||||

Assessed with DES Follow-up: 3–12 months | 102 (one RCT, one nRCT: Bohus et al. 2004; Feigenbaum et al. 2012) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,e for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 83.3 | Mean 0.1 higher (ns) |

Impulsiveness | |||||

Assessed with BIS Follow-up: mean 32 weeks | 84 (one RCT: McMain et al. 2017) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWe for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 55.16 | Mean 1.84 lower (ns) |

Self-harm | |||||

Assessed with DSHI, self-injury, self-mutilation Follow-up: mean 3–12 months | 367 (four RCTs, one nRCT, one observational study: Bohus et al. 2004; Carter et al. 2010; Feigenbaum et al. 2012; Gregory and Sachdeva 2016; McMain et al. 2017; Verheul et al. 2003) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWb,c for greater effect with DBT | Not estimable | Mean score for DHSI at endpoint = 1.14* | Mean 0.34 lower (ns) |

Suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injuries | |||||

Assessed with LSASI Follow-up: mean 32 weeks | 184 (three RCTs: Feigenbaum et al. 2012; McMain et al. 2017; Verheul et al. 2003) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa for greater effect with DBT | – | Mean score at endpoint = 2.56* | |

General psychopathology | |||||

Assessed with SCL-90-R; follow-up: mean 32 weeks | 134 (two RCTs: Bohus et al. 2004; McMain et al. 2017) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa for greater effect with DBT | OR 3.44 (NR) | 184 per 1,000* | |

Functioning | |||||

Assessed with GAF; follow-up: mean 4 months | 50 (one RCT: Bohus et al. 2004) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,e for greater effect with DBT | - | Mean score at endpoint = 49.4 | |

Withdrawal due to adverse events | |||||

Follow-up: 12 months | 41 (one observational study: Gregory and Sachdeva 2016) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,e for similar risks | RR 1 (– to –) | 0 per 1,000 | |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Dialectical Behavior Therapy Versus Mentalization-Based Treatment

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with DBT | Difference in effect with MBT |

Severity of BPD | |||||

Assessed with BEST Follow-up: 12 months | 90 (one nRCT: Barnicot and Crawford 2019) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 35.0 | Mean 0.8 higher (ns) |

Dissociative experiences | |||||

Assessed with DES Follow-up: 12 months | 90 (one nRCT: Barnicot and Crawford 2019) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 30.6 | Mean 4 lower (ns) |

Emotional dysregulation | |||||

Assessed with DERS Follow-up: 12 months | 90 (one nRCT: Barnicot and Crawford 2019) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 103.1 points | Mean 5.6 higher (ns) |

Self-harm incidents | |||||

Assessed with SASII Follow-up: 12 months | 90 (one nRCT: Barnicot and Crawford 2019) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Median number at endpoint was 2.0 | Mean 10.5 more (ns) |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Dialectical Behavior Therapy Versus General Psychiatric Management for Borderline Personality Disorder

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with GPM | Difference in effect with DBT |

Severity of BPD | |||||

Assessed with ZAN-BPD Follow-up: 36 months | 180 (one RCT: McMain et al. 2012) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 6.66 | Mean 1.63 higher (ns) |

Depression | |||||

Assessed with BDI Follow-up: 36 months | 180 (one RCT: McMain et al. 2012) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa,b for greater effect with GPM | – | Mean score at endpoint = 18.05 | Mean 6.40 higher (P = 0.004) |

Interpersonal functioning | |||||

Assessed with IIP Follow-up: 36 months | 180 (one RCT: McMain et al. 2012) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 84.36 | Mean 10.12 higher (ns) |

Nonsuicidal self-injuries | |||||

Assessed with SASII Follow-up: 36 months | 180 (one RCT: McMain et al. 2012) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean number at endpoint = 1.09 | Mean 1.09 more (ns) |

Suicidal episodes | |||||

Assessed with SASII Follow-up: 36 months | 180 (one RCT: McMain et al. 2012) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean number at endpoint = 0.29 | Mean 0.26 more (ns) |

Symptom distress | |||||

Assessed with SCL-90-R total score Follow-up: 36 months | 180 (one RCT: McMain et al. 2012) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 1.03 | Mean 0.23 higher (ns) |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Dialectical Behavior Therapy Versus Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem-Solving

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with DBT | Difference in effect with STEPPS |

Severity of BPD | |||||

Assessed with BSL-23 Follow-up: 6 months | 72 (one nRCT: Guillén Botella et al. 2021) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for greater effect with DBT | – | Mean score at endpoint = 23.56 | Mean 5.73 higher (P= 0.03) |

Anxiety | |||||

Assessed with severity of participants index Follow-up: 6 months | 72 (one nRCT: Guillén Botella et al. 2021) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 8.40 | Mean 0.71 higher (ns) |

Depression | |||||

Assessed with BDI Follow-up: 6 months | 72 (one nRCT: Guillén Botella et al. 2021) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 28.03 | Mean 6.7 lower (ns) |

Dissociation experiences | |||||

Assessed with DES-II Follow-up: 6 months | 72 (one nRCT: Guillén Botella et al. 2021) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 20.81 | Mean 2.8 lower (ns) |

Suicide risk | |||||

Assessed with SRS Follow-up: 6 months | 72 (one nRCT: Guillén Botella et al. 2021) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 7.0 | Mean 1.56 higher (ns) |

Quality of life | |||||

Assessed with QoL Follow-up: 6 months | 72 (one nRCT: Guillén Botella et al. 2021) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 6.31 | Mean 1.16 lower (ns) |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Dialectical Behavior Therapy Versus Dynamic Deconstructive Psychotherapy

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with DBT | Difference in effect with DDP |

Severity of BPD | |||||

Assessed with BEST Follow-up: 12 months | 52 (one observational study: Gregory and Sachdeva 2016) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for greater effect with DDP | – | Mean score at endpoint = 41.8 | Mean 8.8 lower (P= 0.04) |

Depression | |||||

Assessed with BDI Follow-up: 12 months | 52 (one observational study: (Gregory and Sachdeva 2016) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for greater effect with DDP | – | Mean score at endpoint = 27.6 | Mean 10.5 lower (P= 0.009) |

Disability | |||||

Assessed with SDS Follow-up: 12 months | 52 (one observational study: Gregory and Sachdeva 2016) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for greater effect with DDP | – | Mean score at endpoint = 6.1 | Mean 2.3 lower (P= 0.049) |

Self-harm | |||||

Follow-up: 12 months | 52 (one observational study: Gregory and Sachdeva 2016) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for greater effect with DDP | – | Mean number at endpoint = 2.4 | Mean 1.1 fewer (P= 0.02) |

Suicide attempts | |||||

Follow-up: 12 months | 52 (one observational study: Gregory and Sachdeva 2016) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean number at endpoint = 1.3 | Mean 0.74 fewer (ns) |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Dialectical Behavior Therapy Versus Transference-Focused Psychotherapy Versus Supportive Therapy

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with TFP | Difference in effect with DBT |

Anxiety | |||||

Assessed with BSI Follow-up: 12 months | 40 (one RCT: Clarkin et al. 2007) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = NR | NR (ns) |

Depression | |||||

Assessed with BDI Follow-up: 12 months | 40 (one RCT: Clarkin et al. 2007) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = NR | NR (ns) |

Suicidal behaviors | |||||

Assessed with OAS-M Follow-up: 12 months | 40 (one RCT: Clarkin et al. 2007) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = NR | NR (ns) |

Global functioning | |||||

Assessed with GAF Follow-up: 12 months | 40 (one RCT: Clarkin et al. 2007) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = NR | NR (ns) |

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with supportive therapy | Difference in effect with DBT |

Anxiety | |||||

Assessed with BSI Follow-up: 12 months | 39 (one RCT: Clarkin et al. 2007) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = NR | NR (ns) |

Depression | |||||

Assessed with BDI Follow-up: 12 months | 39 (one RCT: Clarkin et al. 2007) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = NR | NR (ns) |

Global functioning | |||||

Assessed with GAF Follow-up: 12 months | 39 (one RCT: Clarkin et al. 2007) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = NR | NR (ns) |

Suicidal behaviors | |||||

Assessed with OAS-M Follow-up: 12 months | 39 (one RCT: Clarkin et al. 2007) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = NR | NR (ns) |

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with TFP | Difference in effect with supportive therapy |

Anxiety | |||||

Assessed with BSI Follow-up: 12 months | 45 (one RCT: Clarkin et al. 2007) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = NR | NR (ns) |

Depression | |||||

Assessed with BDI Follow-up: 12 months | 45 (one RCT: Clarkin et al. 2007) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = NR | NR (ns) |

Global functioning | |||||

Assessed with GAF Follow-up: 12 months | 45 (one RCT: Clarkin et al. 2007) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = NR | NR (ns) |

Suicidal behaviors | |||||

Assessed with OAS-M Follow-up: 12 months | 45 (one RCT: Clarkin et al. 2007) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = NR | NR (ns) |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Dialectical Behavior Therapy Components Versus Other Components of Dialectical Behavior Therapy

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with standard DBT | Difference in effect with DBT group skills training |

Severity of BPD | |||||

Assessed with BSL-23 Follow-up: mean 6 months | 88 (one observational study: Lyng et al. 2020) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 2.56 | Mean 0.51 lower (ns) |

Self-harm acts (NSSI) | |||||

Assessed with SASII Follow-up: mean 2 years | 66 (one RCT: Linehan et al. 2015) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWb,c for similar effects | – | Mean number at endpoint = 7.9 | Mean 1.5 more (ns) |

Suicidal ideation | |||||

Assessed with SBQ and BSS Follow-up: 6 months to 2 years | 154 (one RCT, one observational study: Linehan et al. 2015; Lyng et al. 2020) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWb,c for similar effects | – | Not estimable (different scales) | Mean 4.1 to mean 7.7 lower (ns) |

Suicide attempts | |||||

Assessed with SASII Follow-up: mean 2 years | 66 (one RCT: Linehan et al. 2015) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWb,c for similar effects | – | Mean number at endpoint = 2.0 | Mean 0.5 fewer (ns) |

General psychopathology | |||||

Assessed with SCL-90 Follow-up: mean 6 months | 88 (one observational study: Lyng et al. 2020) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 2.09 | Mean 0.32 lower (ns) |

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with standard DBT | Difference in effect with individual DBT therapy |

Anxiety | |||||

Assessed with Ham-A Follow-up: end of 1-year treatment | 66 (one RCT: Linehan et al. 2015) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 17.2 | Mean 7.1 higher (ns) |

Depression | |||||

Assessed with Ham-D Follow-up: end of 1-year treatment | 66 (one RCT: Linehan et al. 2015) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for greater effect with DBT | – | Mean score at endpoint = 12.3 | Mean 5.9 higher (P = 0.03) |

Self-harm acts (NSSI) | |||||

Assessed with SASII Follow-up: 2 years | 66 (one RCT: Linehan et al. 2015) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean number at endpoint = 7.9 | Mean 8.1 more (ns) |

Suicidal ideation | |||||

Assessed with SBQ Follow-up: 2 years | 66 (one RCT: Linehan et al. 2015) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 28.9 | Mean 3.4 lower (ns) |

Suicide attempts | |||||

Assessed with SASII Follow-up: mean 2 years | 66 (one RCT: Linehan et al. 2015) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean number at endpoint = 2.0 | Mean 1.6 more (ns) |

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with individual DBT therapy | Difference in effect with combined individual plus group therapy DBT |

Self-harm behaviors | |||||

Follow-up: 18 months | 51 (one nRCT: Andión et al. 2012) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean number at endpoint = 22 | Mean 13 fewer (ns) |

Suicide attempts | |||||

Follow-up: 18 months | 51 (one nRCT: Andión et al. 2012) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean number at endpoint = 14 | Mean 8 fewer (ns) |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Dialectical Behavior Therapy Versus Community Therapy by Experts

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with community therapy by experts | Difference in effect with DBT |

Suicide attempts | |||||

Follow-up: mean 2 years | 101 (one RCT: Linehan et al. 2006) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa,b for greater effects with DBT | HR 2.66 (2.40–18.07) | 469 per 1,000 | 345 more per 1,000 (312–531 more) |

Self-harm | |||||

Assessed with mean number of events Follow-up: mean 2 years | 101 (one RCT: Linehan et al. 2006) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean number at endpoint = 3.0 | Mean 0 lower (ns) |

Depression | |||||

Assessed with Ham-D Follow-up: mean 2 years | 101 (one RCT: Linehan et al. 2006) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa,c for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 14.4 | Mean 1.8 lower (ns) |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Dynamic Deconstructive Psychotherapy Versus Treatment as Usual

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies); follow-up | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with TAU | Difference in effect with DDP |

Severity of BPD | |||||

Assessed with BEST Follow-up: mean 12 months | 44 (one observational study: Gregory and Sachdeva 2016) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for greater effects with DDP | – | Mean severity score at endpoint = 42.9 | Mean 9.9 lower (P= 0.006) |

Depression | |||||

Assessed with BDI Follow-up: mean 12 months | 44 (one observational study: Gregory and Sachdeva 2016) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for greater effects with DDP | – | Mean depression score at endpoint = 29.6 | Mean 12.5 lower (P < 0.001) |

Self-injuries | |||||

Follow-up: mean 12 months | 44 (one observational study: Gregory and Sachdeva 2016) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effect | – | Mean number of self-injuries at endpoint = 1.8 | Mean 0.5 lower (ns) |

Suicide attempts | |||||

Follow-up: mean 12 months | 44 (one observational study: Gregory and Sachdeva 2016) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effect | – | Mean number of attempts at endpoint = 1.5 | Mean 0.94 lower (ns) |

Functioning | |||||

Assessed with SDS Follow-up: mean 12 months | 44 (one observational study: Gregory and Sachdeva 2016) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for greater effects with DDP | – | Mean functioning score = 7.0 | Mean 3.2 lower (P < 0.001) |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Mentalization-Based Treatment Versus Treatment as Usual

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with TAU | Difference in effect with MBT (95% CI) |

Severity of BPD | |||||

Assessed with BPFS-C, BPFS-P, ZAN-BPD Follow-up: mean 1 years | 112 (one RCT: Beck et al. 2020) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint for BPFS-C = 71.3; for BPFS-P = 68.7; for ZAN-BPD = 8.0 | Mean for BPFS-C 0 (ns), for BPFS-P 0.1 lower (–7.0 to 7.3), for ZAN-BPD 0.6 lower (95% CI, –4.0 to 2.8) |

BPD symptoms | |||||

Assessed with BDI-Y, RTSHIA Follow-up: mean 1 year | 112 (one RCT: Beck et al. 2020) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint for BDI-Y = 64.3, for RTSHIA = 39.0 | Mean for BDI-Y 0.7 lower (–6.5 to 5.1), for RTSHIA 1.4 lower (–7.1 to 4.3) |

Functioning | |||||

Assessed with CGAS Follow-up: mean 1 year | 112 (one RCT: Beck et al. 2020) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 46.7 | Mean 0.5 higher (–5.8 to 6.7) |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Mentalization-Based Treatment Versus Supportive Therapy

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with supportive therapy | Difference in effect with MBT |

Anxiety | |||||

Assessed with BAI Follow-up: 24 months | 85 (one RCT: Jørgensen et al. 2013) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 15.6 | Mean 2.1 lower (ns) |

Depression | |||||

Assessed with BDI Follow-up: 18–24 months | 219 (two RCTs: Bateman and Fonagy 2009; Jørgensen et al. 2013) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWc,d,e for inconsistent effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 18.68f | Inconsistent findings |

General psychopathology | |||||

Assessed with SCL-90-GSI Follow-up: 18–24 months | 219 (two RCTs: Bateman and Fonagy 2009; Jørgensen et al. 2013) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWc,d,e for inconsistent effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 1.55f | Inconsistent findings |

Global functioning | |||||

Assessed with GAF Follow-up: 18–24 months | 219 (two RCTs: Bateman and Fonagy 2009; Jørgensen et al. 2013) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWc,e for greater effect with MBT | – | Mean score at endpoint = 53.2f | Mean 7.7 higherf (P < 0.001) |

Interpersonal functioning | |||||

Assessed with IIP Follow-up: 18–24 months | 219 (two RCTs: Bateman and Fonagy 2009; Jørgensen et al. 2013) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWc,d,e for inconsistent effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 1.65f | Inconsistent findings |

Severe self-harm incidents | |||||

Assessed with SCL-90-R Follow-up: 18 months | 206 (two RCTs: Bateman and Fonagy 2009; Carlyle et al. 2020) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWd,e for inconsistent effects | – | Mean number at endpoint = 1.66f | Inconsistent findings |

Suicide attempts | |||||

Assessed with SCL-90-R Follow-up: 18 months | 206 (two RCTs: Bateman and Fonagy 2009; Carlyle et al. 2020) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWd,e for inconsistent effects | – | Mean number at endpoint = 0.32f | Inconsistent findings |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Mentalization-Based Treatment Versus Specialized Psychotherapy

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with specialized psychotherapy | Difference in effect with day-hospital MBT |

Severity of BPD | |||||

Assessed with BPDSI Follow-up: 18 months | 95 (one RCT: Laurenssen et al. 2018) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 21.39 | Mean 0.76 lower (ns) |

General psychopathology | |||||

Assessed with GSI of BSI Follow-up: 18–36 months | 299 (one RCT, one observational study; Bales et al. 2015; Laurenssen et al. 2018) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWb,c,d for inconsistent effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 1.04e | Inconsistent findings |

Interpersonal functioning | |||||

Assessed with IIP Follow-up: 18 months | 95 (one RCT: Laurenssen et al. 2018) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = NR | NR (ns) |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving Versus Treatment as Usual

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with TAU | Difference in effect with STEPPS |

Severity of BPD | |||||

Assessed with ZAN-BPD, BPD-40, BEST Follow-up: mean 20 weeks to 2 years | 240 (two RCTs, one prospective cohort: Blum et al. 2008; Bos et al. 2010; González-González et al. 2021) | ⨁⨁⨁◯; MODERATE for greater effects with STEPPSa | – | Mean score at primary endpoint on ZAN-BPD = 13.4; on BPD-40 = 88.6; on BEST = 34.1 in trial and 28.8 in cohort | Mean 3.6 lower on ZAN-BPD; 10.4 lower on BPD-40 (P = 0.001); 2.3 lower on BEST (ns) in trial, 17.7 lower in cohort (P < 0.0) |

Depression | |||||

Assessed with BDI Follow-up: mean 20 weeks | 124 (one RCT: Blum et al. 2008) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa,b for greater effect with STEPPS | – | Mean score at primary endpoint = 25.8 | Mean 3.8 higher (P= 0.03) |

Impulsiveness | |||||

Assessed with BIS Follow-up: mean 20 weeks | 124 (one RCT: Blum et al. 2008) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa,b for greater effect with STEPPS | – | Mean score at primary endpoint = 76.8 | Mean 4.1 lower (P = 0.004) |

Self-harm attempts | |||||

Follow-up: mean 1 year | 124 (one RCT: Blum et al. 2008) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa,b for similar effects | Not estimable | NR | (ns) |

Suicide attempts | |||||

Follow-up: mean 1 year | 124 (one RCT: Blum et al. 2008) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa,b for similar effects, | Not estimable | NR | (ns) |

General psychopathology | |||||

Assessed with CGI-S, CGI-I, SCL-90 Follow-up: 20 weeks to 1 year | 203 (two RCTs: Blum et al. 2008; Bos et al. 2010) | ⨁⨁⨁◯; MODERATE for greater effects with STEPPSa | – | Varied by study and measure | P ≤ 0.03 |

Quality of life | |||||

Assessed with WHOQOL Follow-up: mean 1 year | 79 (one RCT: Bos et al. 2010) | ⨁⨁⨁◯; MODERATEb for greater effect with STEPPS | – | Mean score at primary endpoint = 11.3 | Mean 1.3 higher (0 to 0) |

Functioning | |||||

Assessed with GAS, SAS Follow-up: mean 20 weeks | 124 (one RCT: Blum et al. 2008) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa,b for greater effect with STEPPS | – | Mean score at primary endpoint on GAS = 43.5; on SAS = 26.3 | Mean 7 higher on GAS (ns); 1.7 lower on SAS (ns) |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Transference-Focused Psychotherapy Versus Treatment by Experienced Community Psyhcotherapists

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effects with treatment by experienced community psychotherapists | Difference in effect with TFP |

Severity of BPD symptoms | |||||

Assessed with proportion meeting fewer than five DSM-IV diagnostic criteria Follow-up: mean 1 year | 104 (one RCT: Doering et al. 2010) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa,b for greater effect with TFP | RR 2.23 (1.07–4.65) | 154 per 1,000 | 189 more per 1,000 (11 more to 562 more) |

Anxiety | |||||

Assessed with STAI Follow-up: mean 1 year | 104 (one RCT: Doering et al. 2010) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,c for similar effect | – | Mean score at endpoint for state = 50.47; for trait anxiety = 55.49 | Mean score for state 2.30 higher and for trait anxiety 0.43 lower (ns) |

Depression | |||||

Assessed with BDI Follow-up: mean 1 year | 104 (one RCT: Doering et al. 2010) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,c for similar effect | – | Mean score at endpoint = 20.02 | Mean 1.65 higher (ns) |

Suicide attempts | |||||

Assessed with proportion with any suicide attempts Follow-up: mean 1 year | 104 (one RCT: Doering et al. 2010) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,d for similar effect | RR 0.63 (0.27–1.51)* | 135 per 1,000 | 50 fewer per 1,000 (98 fewer to 69 more) |

General psychopathology | |||||

Assessed with BSI Follow-up: mean 1 year | 104 (one RCT: Doering et al. 2010) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,c for similar effect | – | Mean score at endpoint = 1.27 | MD 0.06 higher (ns) |

Functioning | |||||

Assessed with GAF Follow-up: mean 1 year | 104 (one RCT: Doering et al. 2010) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa,b for greater effect with TFP | – | Mean score at endpoint = 56.06 | Mean 2.6 higher (P= 0.001) |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Transference-Focused Psychotherapy Versus Schema-Focused Therapy

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with TFP | Difference in effect with SFT |

Severity of BPD | |||||

Assessed with BPDSI Follow-up: 3 years | 88 (one RCT: Giesen-Bloo et al. 2006) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for greater effect with SFT | – | Mean score at endpoint = 21.87 | Mean 5.63 lower (P= 0.005) |

Quality of life | |||||

Assessed with EQ Follow-up: 3 years | 88 (one RCT: Giesen-Bloo et al. 2006) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 67.5 | Mean 3.0 lower (ns) |

Assessed with WHOQOL Follow-up: 3 years | 88 (one RCT: Giesen-Bloo et al. 2006) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 11.09 | Mean 0.5 higher (ns) |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Psychotherapy for Special Populations

Comprehensive validation therapy plus 12-step versus dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder and substance use disorder

Mentalization-based treatment plus substance use disorder treatment versus substance use disorder treatment alone for borderline personality disorder and substance use disorder

Dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy versus treatment as usual in the community for borderline personality disorder and alcohol use disorder

Dialectical behavior therapy plus dialectical behavior therapy–prolonged exposure versus dialectical behavior therapy alone for borderline personality disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder

Cognitive-behavioral therapy versus dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder and eating disorders

Specialist supportive clinical management versus modified mentalization- based treatment for borderline personality disorder and eating disorders

Cognitive therapy plus fluoxetine versus interpersonal therapy plus fluoxetine for borderline personality disorder and major depressive disorder

Individual drug counseling versus integrative borderline personality disorder— oriented adolescent family therapy for borderline personality disorder and substance use disorder among adolescents

Manualized good clinical care versus cognitive analytic therapy for adolescents with borderline personality disorder

Grading of the Overall Supporting Body of Research Evidence for Benefits of Psychotherapy in Borderline Personality Disorder

Grading of the Overall Supporting Body of Research Evidence for Harms of Psychotherapy in Borderline Personality Disorder

Pharmacotherapy

Statement 6 – Clinical Review Before Medication Initiation

Grading of the Overall Supporting Body of Research Evidence for Clinical Review Before Medication Initiation in Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder

Statement 7 – Pharmacotherapy Principles

Second-Generation Antipsychotics Versus Placebo

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with placebo | Difference in effect with SGA |

Severity of BPD | |||||

Assessed with ZAN-BPD Follow-up: range 8–12 weeks | 860 (three RCTs: Black et al. 2014; Schulz et al. 2008; Zanarini et al. 2011b) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa for no effect of SGA | – | Mean score at endpoint = 10.3* | Mean 1.2 lower |

Anger | |||||

Assessed with STAXI Follow-up: mean 8 weeks | 52 (one RCT: Nickel et al. 2006) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWb for effect of SGA | – | Mean score at endpoint = 26.2 | Mean 7.7 lower (P < 0.001) |

Aggression | |||||

Assessed with MOAS Follow-up: range 8–12 weeks | 610 (four RCTs: Black et al. 2014; Bogenschutz and Nurnberg 2004; Linehan et al. 2008; Zanarini et al. 2011b) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa,c for no effect of SGA | – | Mean score at endpoint = 18.6* | Mean 14.7 lower (ns) |

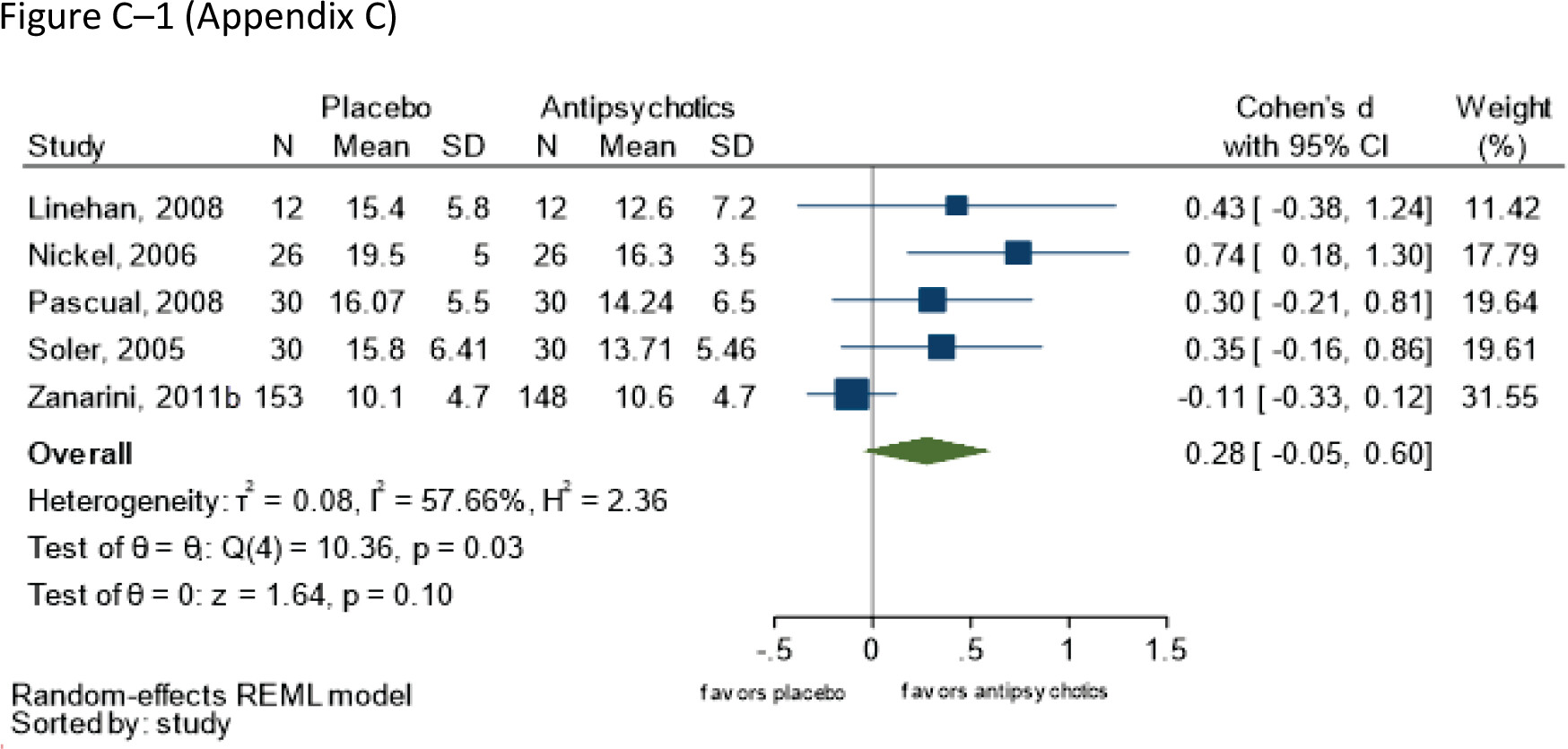

Depression | |||||

Assessed with Ham-D and MADRS Follow-up: range 8–21 weeks | 497 (five RCTs: Gunderson et al. 2011; Linehan et al. 2008; Nickel et al. 2006; Pascual et al. 2008) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWd,e for no effect of SGA | – | Mean score at endpoint = NR | Mean 0.28 SDs (Cohen’s d) greater (-0.05 to 0.60) |

Impulsiveness | |||||

Assessed with BIS Follow-up: range 8–12 weeks | 155 (two RCTs: Black et al. 2014; Pascual et al. 2008) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWd,f for no effect of SGA | – | Mean score at endpoint = 69.1* | Mean 1.4 lower (ns) |

General psychopathology | |||||

Assessed with SCL-90 Follow-up: range 8–12 weeks | 698 (five RCTs: Black et al. 2014; Bogenschutz and Nurnberg 2004; Nickel et al. 2006; Pascual et al. 2008; Zanarini et al. 2011b) | ⨁⨁⨁◯; MODERATEa for effect of SGA | – | Mean score at endpoint = 10.3* | Mean 1.2 lower (ns) |

Functioning | |||||

Assessed with GAF and SDS Follow-up: mean 8–12 weeks | 586 (three RCTs: Black et al. 2014; Bogenschutz and Nurnberg 2004; Zanarini et al. 2011b) | ⨁⨁⨁◯; MODERATEg for no effect of SGA | – | Mean score at endpoint = 63.2* | Mean 2.9 higher (ns) |

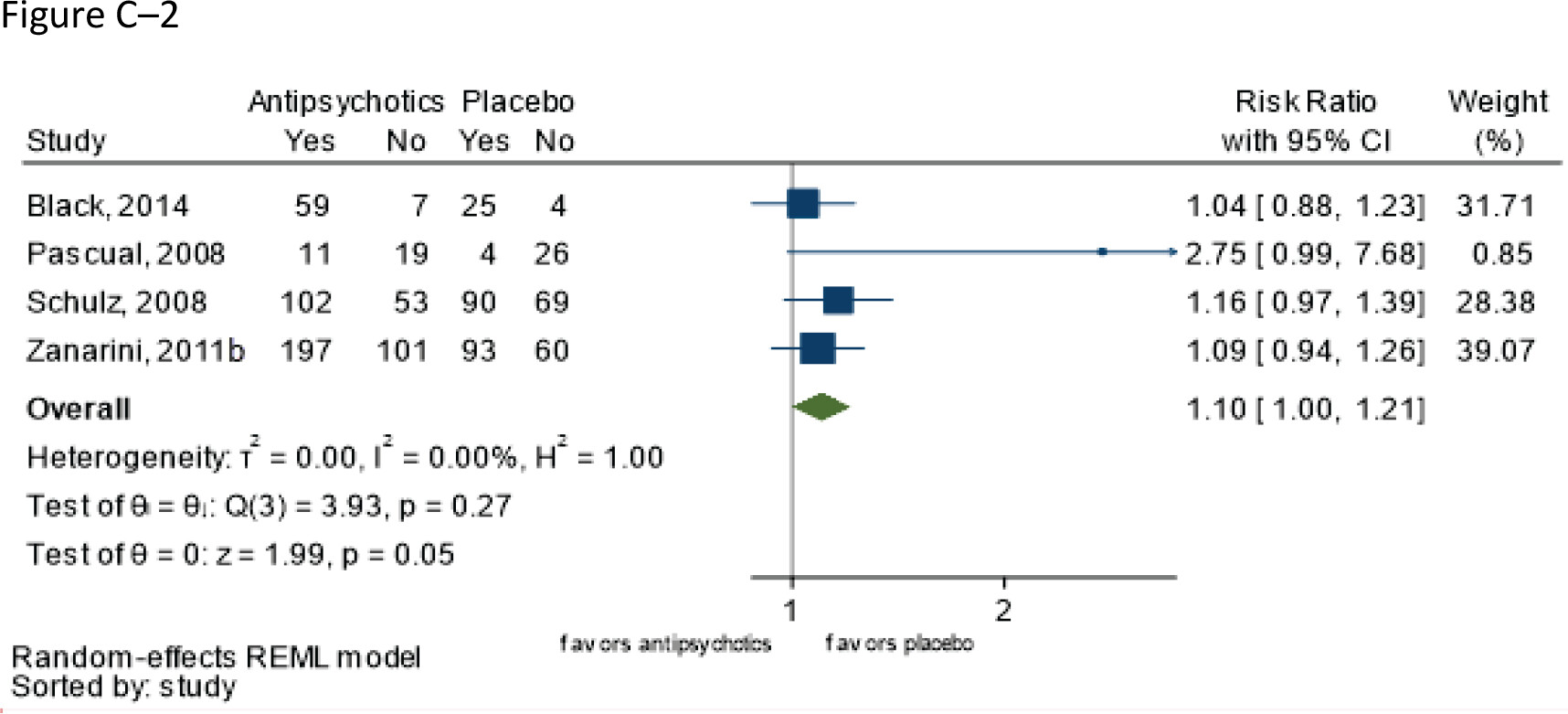

Incidence of adverse events | |||||

Follow-up: range 8–12 weeks | 920 (four RCTs: Black et al. 2014; Pascual et al. 2008; Schulz et al. 2008; Zanarini et al. 2011b) | ⨁⨁⨁◯; MODERATEa for higher risk with antipsychotics | RR 1.10 (1.00–1.21) | 571 per 1,000 | 57 more per 1,000 (0 fewer to 120 more) |

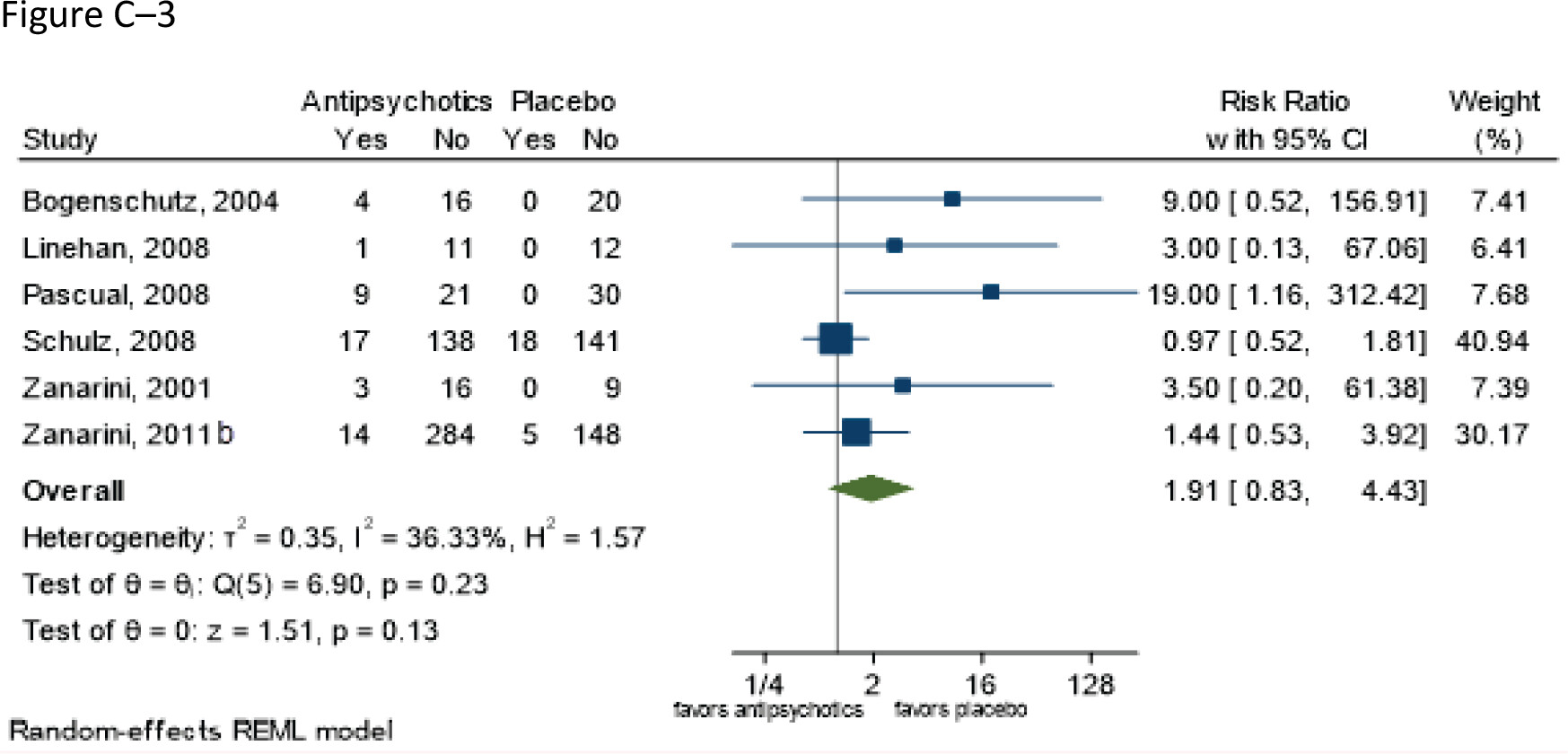

Withdrawal due to adverse events | |||||

Follow-up: range 8–12 weeks | 917 (five RCTs: Bogenschutz and Nurnberg 2004; Pascual et al. 2008; Schulz et al. 2008; Zanarini and Frankenburg 2001; Zanarini et al. 2011b) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWa,h for similar risks | RR 1.91 (0.83–4.43) | 69 per 1,000 | 63 more per 1,000 (12 fewer to 237 more) |

Incidence of serious adverse events | |||||

Follow-up: range 8–12 weeks | 957 (six RCTs: Black et al. 2014; Bogenschutz and Nurnberg 2004; Nickel et al. 2006; Pascual et al. 2008; Schulz et al. 2008; Zanarini et al. 2011b) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOWi for higher risk with placebo | RR 0.46 (0.23–0.95)** | 44 per 1,000 | 24 fewer per 1,000 (34 fewer to 2 fewer) |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Grading of the overall supporting body of research evidence for benefits of second-generation antipsychotics in borderline personality disorder

Grading of the overall supporting body of research evidence for harms of second- generation antipsychotics in borderline personality disorder

Second-Generation Antipsychotic Versus Antidepressant

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with antidepressants | Difference in effect with SGA |

| Olanzapine vs. fluoxetine | |||||

Aggression | |||||

Assessed with MOAS Follow-up: mean 8 weeks | 30 (one RCT: Zanarini et al. 2004c) | ⨁◯◯◯; LOWa for greater effect of olanzapine | – | Mean score at endpoint = 7.83 | Mean 4.3 lower (P = 0.003) |

Depression | |||||

Assessed with MADRS Follow-up: mean 8 weeks | 30 (one RCT: Zanarini et al. 2004c) | ⨁◯◯◯; LOWa for greater effect of olanzapine | – | Mean score at endpoint = 6.2 | Mean 1.0 lower (P < 0.001) |

| Olanzapine + fluoxetine vs. fluoxetine | |||||

Aggression | |||||

Assessed with MOAS Follow-up: mean 8 weeks | 29 (one RCT: Zanarini et al. 2004c) | ⨁◯◯◯ LOWa for greater effect of olanzapine + fluoxetine | – | Mean score at endpoint = 7.83 | Mean 4.8 lower (P < 0.001) |

Depression | |||||

Assessed with MADRS Follow-up: mean 8 weeks | 29 (one RCT: Zanarini et al. 2004c) | ⨁◯◯◯; LOWa for greater effect of olanzapine + fluoxetine | – | Mean score at endpoint = 6.2 | Mean 1.8 lower (P = 0.02) |

Withdrawals due to adverse events | |||||

Follow-up: mean 8 weeks | 29 (one RCT: Zanarini et al. 2004c) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar risks | RR 0.94 (0.06–13.68) | 71 per 1,000 | 4 fewer per 1,000 (67 fewer to 906 more) |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Second-Generation Antipsychotics Versus Second-Generation Antipsychotics

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with olanzapine | Difference in effect with asenapine |

Severity of BPD | |||||

Assessed with BPDSI Follow-up: mean 12 weeks | 51 (one RCT: Bozzatello et al. 2017) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 49.12 | Mean 2.23 lower (ns) |

Aggression | |||||

Assessed with MOAS Follow-up: mean 12 weeks | 51 (one RCT: Bozzatello et al. 2017) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 4.8 | Mean 1.4 higher (ns) |

Impulsiveness | |||||

Assessed with BIS Follow-up: mean 12 weeks | 51 (one RCT: Bozzatello et al. 2017) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 72.9 | Mean 8.2 lower (ns) |

Self-harm | |||||

Assessed with SHI Follow-up: mean 12 weeks | 51 (one RCT: Bozzatello et al. 2017) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 10 | Mean 2 lower (ns) |

Global impression | |||||

Assessed with CGI-S Follow-up: mean 12 weeks | 51 (one RCT: Bozzatello et al. 2017) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar effects | – | Mean score at endpoint = 3.9 | Mean 0.2 lower (ns) |

Incidence of adverse events | |||||

Assessed with DOTES Follow-up: mean 12 weeks | 40 (one RCT: Bozzatello et al. 2017) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for similar risks | RR 1.38 (0.43–4.40) | 263 per 1,000 | 100 more per 1,000 (150 fewer to 895 more) |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

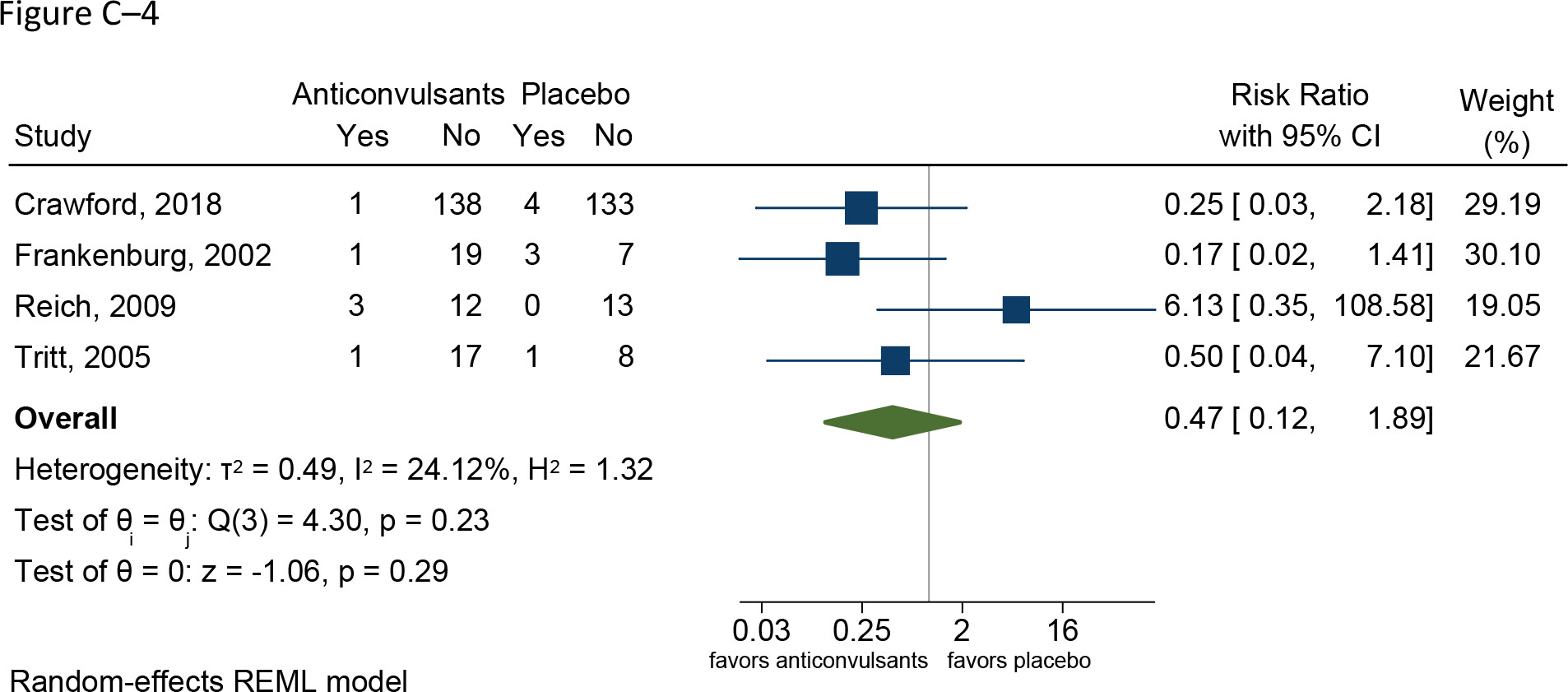

Anticonvulsants Versus Placebo

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with placebo | Difference in effect with anticonvulsants |

| Divalproex sodium | |||||

Severity of BPD | |||||

Assessed with BEST Follow-up: mean 12 weeks | 15 (one RCT: Moen et al. 2012) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for no effect of divalproex sodium | – | Mean score at endpoint = 30.0 | Mean 1.3 lower (ns) |

Aggression | |||||

Assessed with MOAS; SCL-90-R subscale for anger and hostility Follow-up: range 10–24 weeks | 46 (two RCTs: Frankenburg and Zanarini 2002; Hollander et al. 2001) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,c,d for effect of divalproex sodium | – | Mean score on MOAS = 3.2 * | Mean 0.6 lower (P = 0.03) |

Impulsiveness | |||||

Assessed with BIS-Motor Follow-up: mean 12 weeks | 15 (one RCT: Moen et al. 2012) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for no effect of divalproex sodium | – | Mean score at endpoint = 18.2 | Mean 5.7 higher (ns) |

General psychopathology | |||||

Assessed with SCL-90-R, CGI-I Follow-up: range 10–12 weeks | 31 (two RCTs: Hollander et al. 2001; Moen et al. 2012) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,d for no effect of divalproex sodium | – | Mean score at endpoint on SCL-90 = 114.2* | Mean 22.8 higher (ns) |

Withdrawals due to adverse events | |||||

Follow-up: range 10–24 weeks | 46 (two RCTs: Frankenburg and Zanarini 2002; Hollander et al. 2001) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,d for similar risks | RR 0.26 (0.03–2.35) | 136 per 1,000* | 101 fewer per 1,000 (132 fewer to 184 more; ns) |

| Lamotrigine | |||||

Severity of BPD | |||||

Assessed with ZAN-BPD Follow-up: range 12–52 weeks | 304 (two RCTs: Crawford et al. 2018; Reich et al. 2009) | ⨁⨁⨁◯; MODERATEe for no effect of lamotrigine | – | Mean score at endpoint = 11.5* | Mean 0.5 lower (ns) |

Affective lability | |||||

Assessed with ALS Follow-up: mean 12 weeks | 28 (one RCT: Reich et al. 2009) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWb,f for effect of lamotrigine | – | Mean score at endpoint = 1.52 | Mean 0.27 lower (P = 0.012) |

Alcohol and substance use | |||||

Assessed with ASSIST Follow-up: mean 52 weeks | 160 (one RCT: Crawford et al. 2018) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWb for no effect of lamotrigine | – | Mean score at endpoint = 23 | Mean 4 higher (ns) |

Anger | |||||

Assessed with STAXI Follow-up: mean 8 weeks | 27 (one RCT: Tritt et al. 2005) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWb for effect of lamotrigine | – | NR | NR (four of five subscales significantly improved) |

Functioning | |||||

Assessed with SFQ Follow-up: mean 52 weeks | 276 (one RCT: Crawford et al. 2018) | ⨁⨁⨁◯; MODERATEe,g for no effect of lamotrigine | – | Mean score at endpoint = 12.3 | Mean 0.1 higher (ns) |

Incidence of adverse events | |||||

Follow-up: range 10–52 weeks | 304 (two RCTs: Crawford et al. 2018; Reich et al. 2009) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWg for similar risks | RR 0.86 (0.71–1.03) | 630 per 1,000* | 88 fewer per 1,000 (183 fewer to 19 more; ns) |

Incidence of serious adverse events | |||||

Follow-up: mean 52 weeks | 276 (one RCT: Crawford et al. 2018) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWh for similar risks | RR 0.82 (0.52–1.31) | 230 per 1,000 | 41 fewer per 1,000 (111 fewer to 71 more; ns) |

Withdrawal due to adverse events | |||||

Follow-up: range 10–52 weeks | 328 (three RCTs: Crawford et al. 2018; Reich et al. 2009; Tritt et al. 2005) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWh,i for similar risks | RR 3.79 (0.82–17.57) | 12 per 1,000 | 35 more per 1,000 (2 fewer to 206 more; ns) |

| Topiramate | |||||

Anger | |||||

Assessed with STAXI Follow-up: mean 8 weeks | 75 (two RCTs: Nickel et al. 2004; Nickel et al. 2005) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWd for effect of topiramate | – | NR | NR (four of five subscales significantly improved) |

General psychopathology | |||||

Assessed with SCL-90 Follow-up: range 8–12 weeks | 56 (one RCT: Loew et al. 2006) | ⨁⨁◯◯; LOWb for effect of topiramate | – | Mean score at endpoint = 70.1 | Mean 5.9 lower (P < 0.001) |

Withdrawal due to adverse events | |||||

Follow-up: mean 8 weeks | 75 (two RCTs: Nickel et al. 2004; Nickel et al. 2005) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWd,j for similar risks | RR 1.95 (0.77–4.94) | 0 per 1,000 | 0 fewer per 1,000 (0 fewer to 0 fewer) |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Divalproex sodium

Lamotrigine

Topiramate

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Divalproex sodium

Lamotrigine

Topiramate

Global impression and functioning

Divalproex sodium

Lamotrigine

Topiramate

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Divalproex sodium

Lamotrigine

Topiramate

Grading of the overall supporting body of research evidence for benefits of divalproex in borderline personality disorder

Grading of the overall supporting body of research evidence for harms of divalproex in borderline personality disorder

Grading of the overall supporting body of research evidence for benefits of lamotrigine in borderline personality disorder

Grading of the overall supporting body of research evidence for harms of lamotrigine in borderline personality disorder

Grading of the overall supporting body of research evidence for benefits of topiramate in borderline personality disorder

Grading of the overall supporting body of research evidence for harms of topiramate in borderline personality disorder

Second-Generation Antidepressants Versus Placebo

| Anticipated absolute effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Participants, N (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Effect with placebo | Difference in effect second-generation antidepressants |

Anger | |||||

Assessed with STAXI Follow-up: mean 10 weeks | 25 (one RCT: Simpson et al. 2004) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for no effect of fluoxetine | – | Mean score at endpoint = 27.6 | Mean 7.1 lower (ns) |

Aggression | |||||

Assessed with MOAS Follow-up: mean 10 weeks | 25 (one RCT: Simpson et al. 2004) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for no effect of fluoxetine | – | Mean score at endpoint = NR | NR (ns) |

Functioning | |||||

Assessed with GAF Follow-up: mean 10 weeks | 25 (one RCT: Simpson et al. 2004) | ⨁◯◯◯; VERY LOWa,b for no effect of fluoxetine | – | Mean score at endpoint = 59.3 | Mean 0.6 higher (ns) |

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Grading of the overall supporting body of research evidence for antidepressants in borderline personality disorder

Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Versus Sham Treatment

Severity of borderline personality disorder

Severity of symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder

Global impression and functioning

Incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events

Grading of the overall supporting body of research evidence for repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in borderline personality disorder

Statement 8 – Pharmacotherapy Review

Grading of the Overall Supporting Body of Research Evidence for Pharmacotherapy Review in Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

Authors

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.