Some studies have found that depressive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia may be secondary to negative symptoms

(1), medications

(2), or neuroleptic-induced movement disorders

(2), whereas others have reported that in patients with chronic schizophrenia

(3–

7) and even first-episode schizophrenia

(8), depressive symptoms may be a core component of various stages of this illness. Estimates of the frequency of depressive episodes in patients with schizophrenia range from 20% to 80%

(9,

10). Differences in cohort status, illness chronicity, and assessment methods all contribute to the variability of these estimates.

Depression during the acute phase of schizophrenia may be associated with a favorable course and outcome

(11), but several studies have suggested that depression during the chronic phase of schizophrenia is associated with a greater risk of suicide

(12–

15) and relapse

(15). While most of these investigations have focused on depression in younger adults with schizophrenia, one study reported that among schizophrenic patients aged 55 and older, high scores on a depression rating scale were associated with positive symptoms, physical limitations interfering with activities, diminished social networks, and lower income

(13). Unfortunately, this otherwise interesting study did not include nonschizophrenic control subjects or large enough samples to evaluate the contributions of age and gender.

In the present investigation, our primary aim was to assess the relative frequency and the degree of depressive symptoms in a clinically stable group of mid- to late-life outpatients with schizophrenia who were not diagnosed with concurrent major depression or schizoaffective disorder. We hypothesized that 1) depressive symptoms would be more frequent in schizophrenic patients than in an age- and gender-proportionally matched group of normal comparison subjects; 2) on the basis of studies of community samples of the general population

(16), depressive symptoms would be more frequent and more severe in women and younger individuals; and 3) depressive symptoms would be significantly associated with positive symptoms but not with negative symptoms, use of antipsychotic medications, or neuroleptic-induced movement disorders.

RESULTS

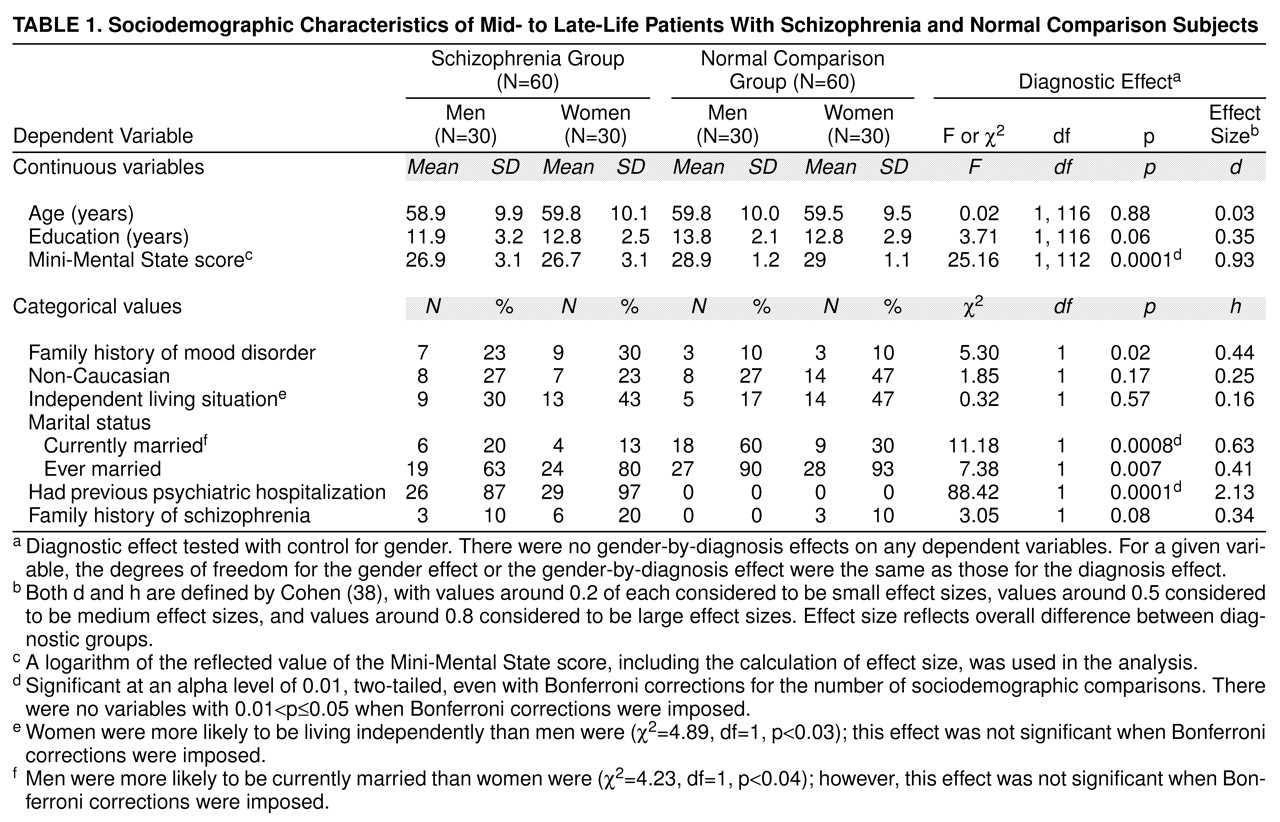

As can be seen in

table 1, the groups were well matched on most demographic features. As expected, schizophrenic patients were more likely to have had previous psychiatric hospitalizations, were less likely to be currently married, and had lower scores on the Mini-Mental State than normal comparison subjects. No diagnosis-by-gender interaction effects were significant.

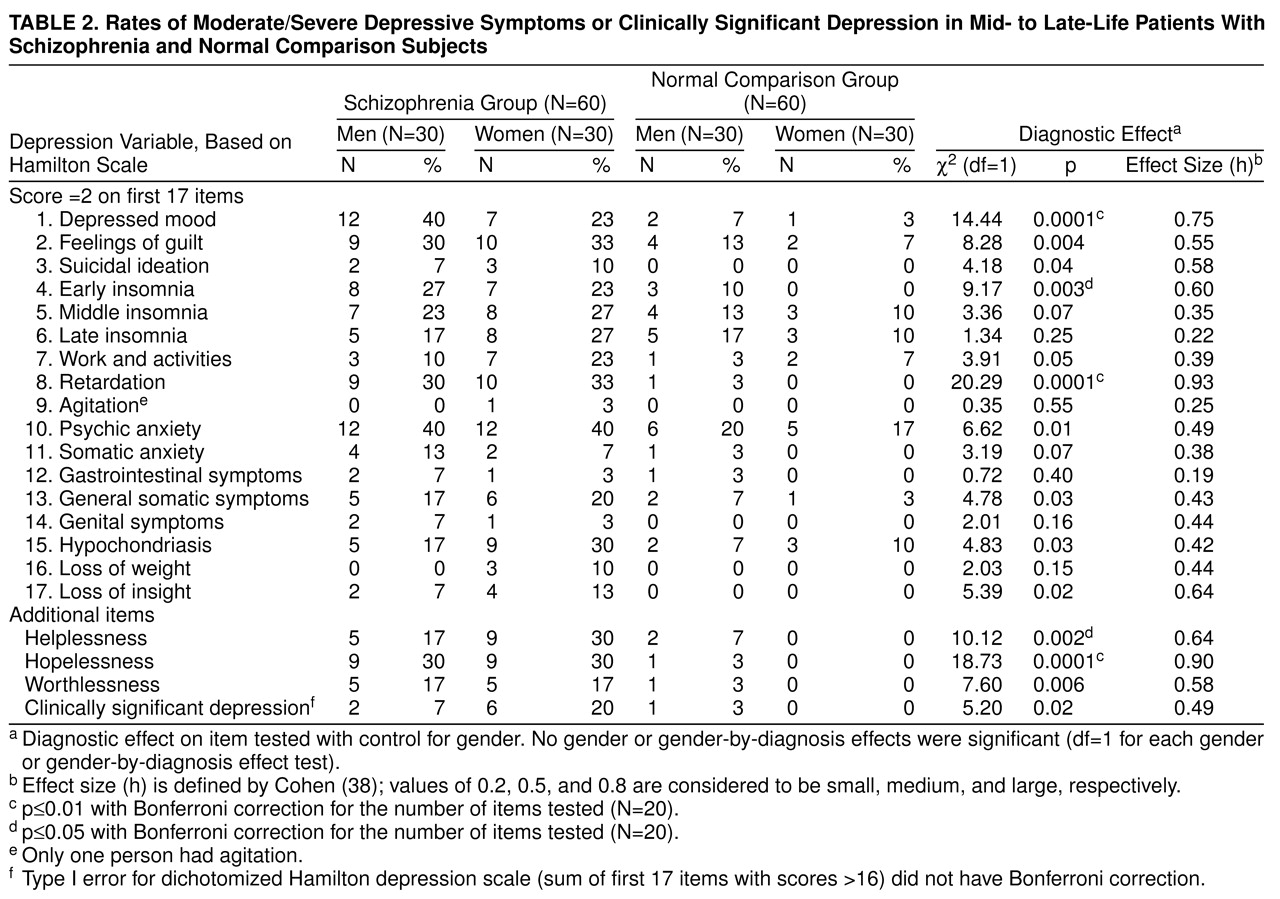

Table 2 lists, for each of the four groups, percentages of individuals with depressive symptoms (score of 2 or more) rated on each of the first 17 items of the Hamilton depression scale. Three additional items that may reflect some of the more severe psychological symptoms of depression—helplessness, hopelessness, and worthlessness—were also tabulated. Each of the depressive symptoms was more frequent in schizophrenic patients than in normal subjects. Log linear model analysis (likelihood ratio tests) revealed that these diagnostic differences were significant for 12 of the 17 items and for each of the three additional psychological symptoms of depression. With the Bonferroni correction, three of the 17 items and two of the three additional items were still significant. The effect on total dichotomized 17-item Hamilton depression scale score was medium and significant

(38). No gender or gender-by-diagnosis interaction effects were significant for any individual item for the 17-item Hamilton depression scale score.

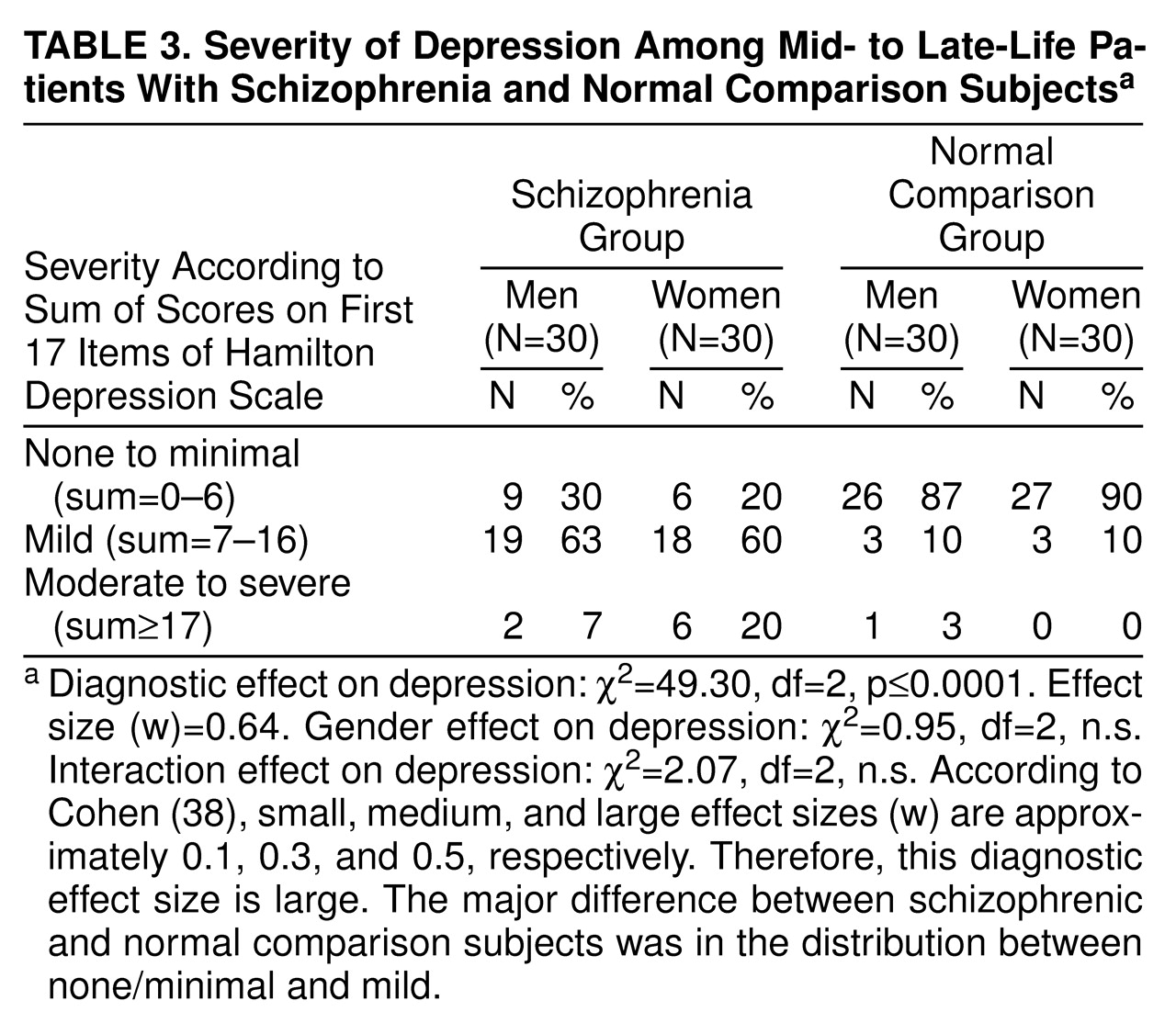

The percentages of individuals with scores of 17 or more, between 7 and 16, and 6 or less on the first 17 items of the Hamilton depression scale are given in

table 3. These cutoff points were selected because they have previously been shown to represent relatively moderate to severe depression severity (score of 17 or more on the first 17 items of the Hamilton depression scale), mild severity (score of 7 to 16), and minimal severity (score of 6 or less)

(39). In addition, table 3 shows the log linear model statistical tests (likelihood ratio tests) of the partial associations between the predictors (diagnostic and gender main effects and their interaction) and depression severity categories. The diagnostic effect was large and significant

(38). Both male and female patients with schizophrenia were more likely to meet criteria for mild or moderate/severe depression than normal subjects were. Neither gender nor interaction between diagnosis and gender had significant effects on severity of depression (trichotomized 17-item Hamilton depression scale score).

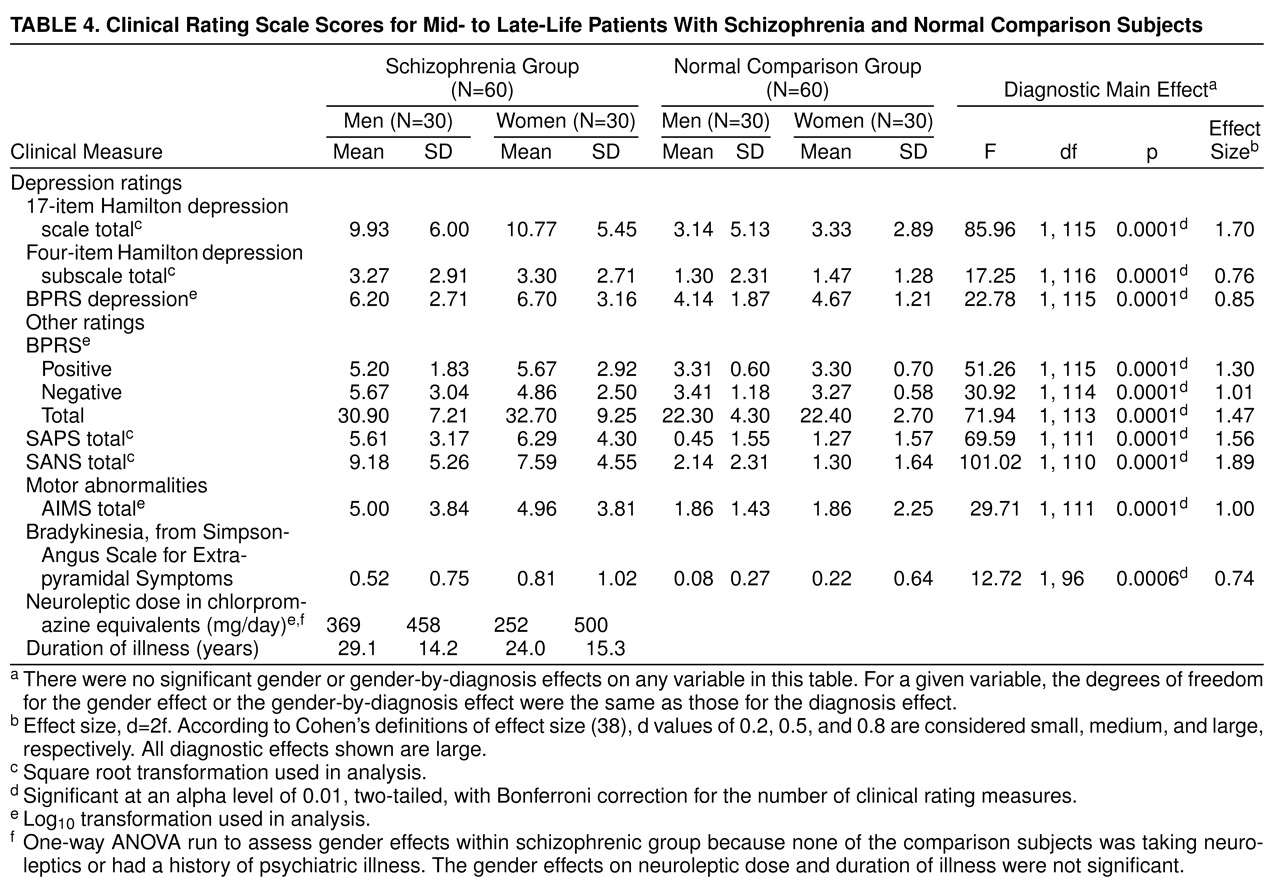

Table 4 shows the mean scores for each of the clinical measures for male and female patients with schizophrenia and male and female normal subjects. ANOVA F ratio tests revealed that schizophrenic patients had higher scores on each of the rating scales measuring depression, as well as on BPRS total and positive and negative symptom subscales, and on SAPS and SANS total scores. In addition, schizophrenic patients had higher AIMS and modified Simpson-Angus bradykinesia item scores. There were no significant differences on any of the measures based on gender, and there were no significant diagnosis-by-gender interactions.

The most frequently used antipsychotics were haloperidol (N=15), perphenazine (N=11), chlorpromazine (N=5), thioridazine (N=5), risperidone (N=3), and clozapine (N=2); and one patient had participated in a study of remoxipride. Seven patients were taking more than one neuroleptic. In addition, 24 (40%) of the schizophrenic patients were taking concomitant anticholinergic agents to control extrapyramidal symptoms, three (5%) were taking lithium, 15 (25%) were taking antidepressant medication, and eight (13%) were taking anxiolytic medication. Of the 15 patients prescribed antidepressant medications by their referring physicians, five were taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, three were taking trazodone (doses of 50, 150, and 400 mg/day), and seven were taking tricyclic antidepressants (in doses ranging between 10 mg imipramine to 300 mg amitriptyline). We compared the patients who were taking antidepressant medications to those who were not, on the 17-item Hamilton depression scale total score and on the percentage of subjects classified as minimally, mildly, and moderately to severely depressed. There were no differences between groups on any of these measures.

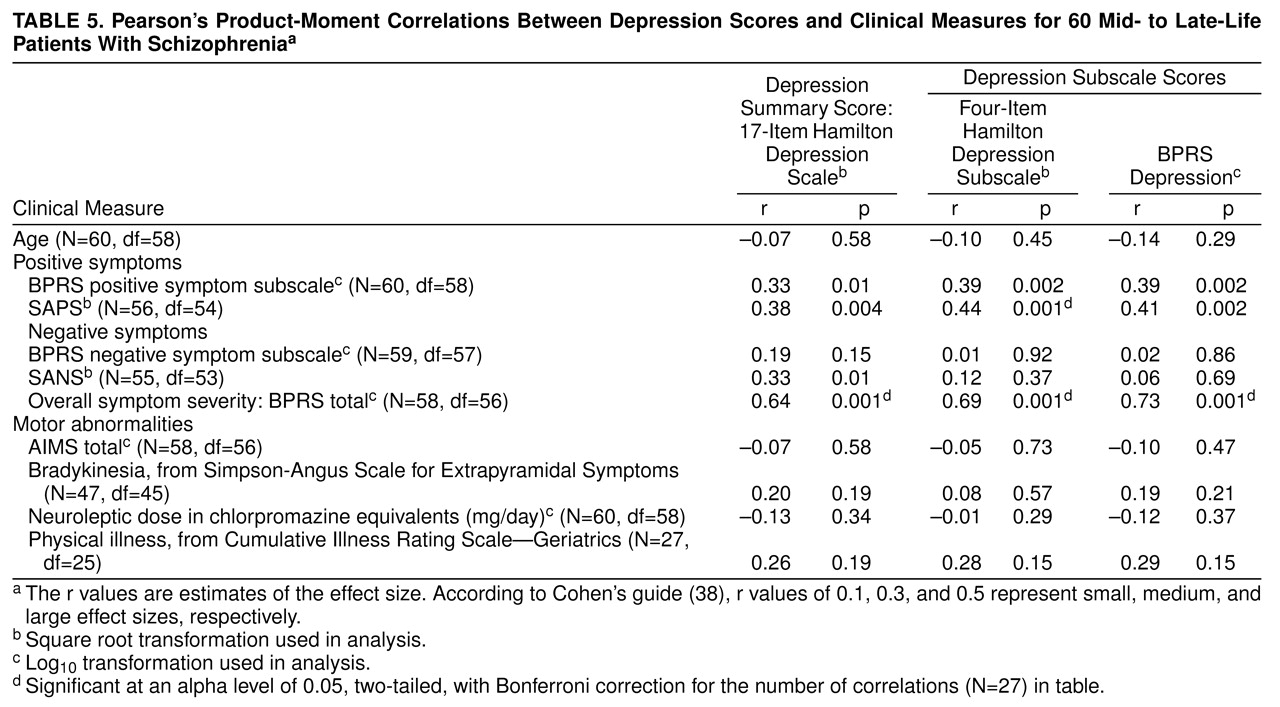

For the schizophrenic patients only, the relationship of the depression scores with age and other clinical measures is shown in

table 5 as Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficients, which are themselves estimates of the effect size

(38). The effects significant with Bonferroni correction are footnoted as such. The correlation between severity of depression and either age or daily neuroleptic dose was low, negative, and nonsignificant. There were large and significant positive correlations between depression and severity of overall symptoms (BPRS total score) and medium to medium/large associations with positive symptoms (measured by either the BPRS positive symptom subscale or the SAPS). The correlation between the SAPS and four-item Hamilton depression subscale retained significance even with the Bonferroni correction for the number of correlations assessed in

table 5 (alpha=0.05, two-tailed). Correlations between depression and negative symptoms were low to medium depending on how depression and negative symptoms were measured. None of the depression scale scores was significantly correlated with the total AIMS score, the bradykinesia item score, or the total score on the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale—Geriatrics.

On the basis of these results, an additional post hoc analysis was performed. Because of the relatively high proportion of schizophrenic patients with a family history of mood disorders, the relationship between family history and depressive symptoms was assessed. The percentage of schizophrenic patients with 17-item Hamilton depression scale scores of 17 or more was not significantly greater in the group with a family history of mood disorders than in the group without such a history (19% versus 11%) (χ2=0.55, df=1, p=0.46), the trichotomous 17-item Hamilton depression scale was not significantly related to family history (χ2=2.02, df=2, p=0.31), and the mean total score on the 17-item Hamilton depression scale was not significantly greater in the group with a family history of mood disorders than in the group without such a history (11.8 versus 9.8) (t=–1.15, df=1, 58, p=0.25).

DISCUSSION

Depressive symptoms seemed to be a part and parcel of schizophrenia, even in a cohort specifically defined so as not to be in a major depressive episode or to have schizoaffective disorder. For both men and women with schizophrenia, depressive symptoms were frequent and did not appear to be simply a by-product of age, neuroleptics, family history, negative symptoms, or movement disorder. On the other hand, there was an association between depressive symptoms and positive symptoms, confirming Cohen’s findings

(13).

This study had several strengths. First, the research group included only mid-life and older individuals, thus providing data on a cohort of schizophrenic patients largely overlooked in previous studies. Second, an equal number of gender- and age-matched normal comparison subjects was studied with the same instruments. Third, psychometrically sound instruments were used. Although the Hamilton depression scale was not designed as a measure of depressive symptoms for schizophrenic patients, it has been used in numerous studies to measure severity of depressive symptoms in schizophrenic patients, and factor analytic studies have found discrete factors reliable and valid for this population

(33). Depressive symptoms also were measured with a subscale of the BPRS, an instrument widely employed in studies of schizophrenic patients

(21).

There also are several limitations to the study. Although 120 subjects represent a relatively large group, a larger group would have allowed us to look at other clinically important subtypes (such as late-onset versus early-onset schizophrenia and paranoid versus nonparanoid patients). Similarly, because the group was limited to individuals over age 45, it was not possible to study age effects throughout the age spectrum. The somewhat unexpected finding that 10% of the female comparison subjects reported a family history of schizophrenia raises a question about the representativeness of the comparison population. However, that 10% amounted to only three of a total of 60 comparison subjects and could simply be a chance finding. Finally, the study was cross-sectional; a longitudinal design would permit one to learn more about the meaning, course, and consequences of depressive symptoms in these patients.

Although one of four schizophrenic patients was taking antidepressant medications, none of the patients was diagnosed by the SCID or at the consensus diagnostic conference as having a present or past major depressive episode. Furthermore, no differences in depression severity ratings were found between patients treated and those not treated with antidepressants. In many cases, the medication may have been given to treat insomnia, since subantidepressant doses of relatively sedating antidepressants often were given; in other cases, physicians may have been attempting to treat dysphoria or demoralization. The frequency with which such symptoms are routinely treated in clinical practice previously has been pointed out

(40). If these medications are at all effective in ameliorating depressive symptoms, our findings regarding the frequency and intensity of depressive symptoms in schizophrenic patients are overly conservative. The spectrum of depressive symptoms seen in schizophrenic patients was broad. The greatest differences in depressive symptoms between the schizophrenic and normal groups (and largest effect sizes) were observed in terms of the severity of feelings of hopelessness and helplessness, psychomotor retardation, and depressed mood, but most other depressive symptoms also were frequent in schizophrenic patients. Although they did not meet the criteria for major depressive disorder, one-fifth of the female schizophrenic patients had 17-item Hamilton depression scale scores of 17 or more; a score of 17 generally reflects at least moderate levels of depression and is often used as an entrance threshold for antidepressant trials. When lesser degrees of depression were taken into account, the overwhelming majority of both men and women with schizophrenia had at least subsyndromal symptoms of depression. The clinical importance of this finding is underscored by several studies demonstrating that subsyndromal depression symptoms in nonpsychotic patients are associated with considerable social dysfunction and disability

(40–

43), suicide attempts (43), and risk of later major depressive episodes

(44,

45). It also is worth noting that the 10% rate of mild depressive symptoms in our normal comparison group is well in line with the rate of subsyndromal depression seen in community samples

(41).

In this study, gender was not consistently associated with increased risk of depression. Thus, our results are not consistent with what one might have expected on the basis of epidemiological studies of depression in nonschizophrenic individuals living in the community

(16) or some studies of younger individuals with schizophrenia that show men with a more severe illness than women

(46). Perhaps a larger group might have revealed more significant findings in terms of gender.

The rates of family members with depression generally are consistent with the rates found in younger schizophrenic patients in community samples

(10). However, there was no relationship between family history of depression and the presence of depressive symptoms in these patients. In contrast, a recently published study of younger individuals with schizophrenia found a significant association between depressive symptoms and family history of unipolar affective illness

(47). Perhaps this discrepancy between their findings and ours relates to sampling differences, since the previously published study sampled mostly men, all of whom were under age 45 years (mean age=24 years) and had recently experienced their first psychotic episode. Our inability to find a significant relationship between family history and current symptoms of depression supports Kay and Murrill’s notion that depression may be a core manifestation of schizophrenia

(48), rather than simply a by-product of a familial risk of comorbidity.

All depression scales had moderate to large correlations with positive symptoms; the correlation between the four-item Hamilton depression subscale and the SAPS maintained a significant association even with Bonferroni corrections. On the other hand, relationships with severity of negative symptoms were less consistent in size, and all were nonsignificant with Bonferroni corrections. Thus, as in some recent studies, depressive symptoms seemed to be more closely aligned with positive than with negative symptoms of schizophrenia

(49–

51). Whether depressive symptoms are a core component of schizophrenia or, alternatively, are a result of living with persistent, severe psychosis cannot be determined by this study, but it remains a question worthy of further investigation.

In conclusion, the results confirmed our first hypothesis concerning the greater occurrence of depressive symptoms in schizophrenic patients than in age- and gender-matched normal comparison subjects. The second hypothesis was not confirmed in this study; neither younger age nor female gender was consistently associated with greater occurrence or severity of depressive symptoms. Our third hypothesis was partially confirmed: depression was not associated with medication dose or neuroleptic-induced motor symptoms, but, depending on the measures of depression used and the degree of control of type I error imposed, depression severity was associated with positive but not negative symptoms. Thus, depression may be a concomitant response to psychotic symptoms—a by-product and yet a common feature of schizophrenia, or it could be a relatively independent, albeit overlapping, aspect of schizophrenia. An important next step would be to extend these findings to the entire age range of patients with schizophrenia, to assess the course and consequences of symptoms of depression over suitable follow-up periods with larger groups, and to measure the frequency and severity of depressive symptoms in patients with low, moderate, and high levels of psychotic symptoms.