Over the last several decades, disorders of body image have grown increasingly common among men in Western societies

(1). Body dysmorphic disorder, once considered uncommon

(2), is now recognized as a common disorder afflicting 1% to 2% of Western men

(3–

5). One form of this disorder, “muscle dysmorphia,” characterized by a pathological preoccupation with muscularity

(6,

7), appears to be growing in prevalence and severity among Western men

(1,

7–9). These pathological body image concerns, sometimes popularly called the “Adonis complex,” have attracted much attention in Western media

(10–

13). By contrast, male body image disorders appear to be rare in non-Western societies; for example, we are aware of only a single case report of muscle dysmorphia in Asia

(14).

Why do Western men seem so vulnerable to body image problems? Recent studies suggest two possible explanations: 1) Western men may harbor unrealistic body ideals, and 2) Western society is placing an increasing “value” on the male body.

We examined the first of these two phenomena: it has long been recognized that Western women may have body image problems

(22–

25), but only recently have studies focused on men

(1,

26). We have recently attempted to augment this research by creating a computerized measure of body image perception, the “somatomorphic matrix”

(27). This instrument, described in detail previously

(27,

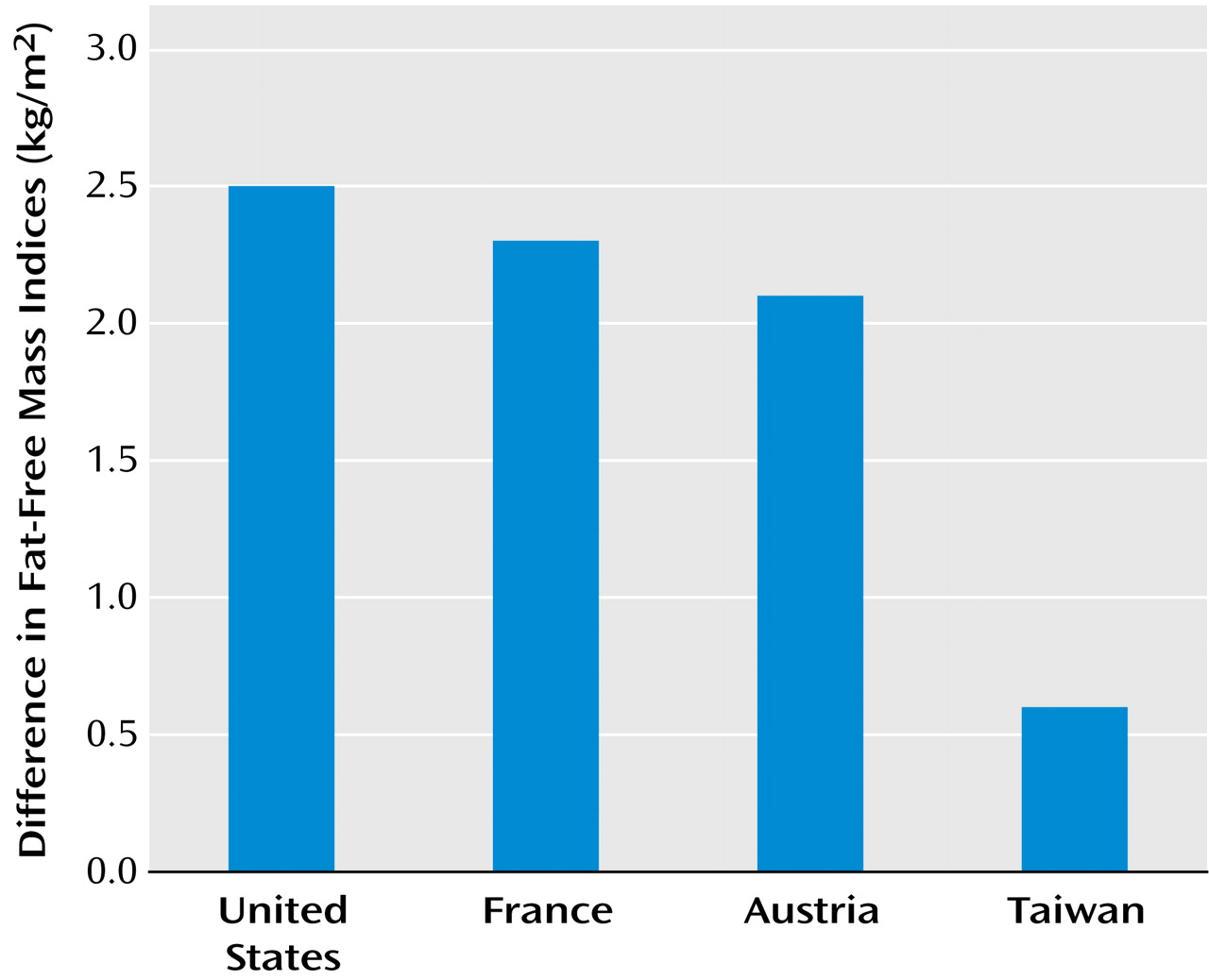

28), presents the subject with an image of a male body that he can adjust on the computer screen through 10 levels of muscularity and 10 levels of fat (i.e., a total of 100 possible images). The subject is then asked to choose the images best representing 1) his own body, 2) the body of an average man of his age in his country, 3) the body that he ideally would like to have, and 4) the body that he thinks that women would prefer the most. When we administered the somatomorphic matrix to college-age men in the United States, France, and Austria, subjects in all three countries picked an ideal body image that was about 28 lb (13 kg) more muscular than themselves, and they estimated that women preferred a male body about 30 lb (14 kg) more muscular than themselves

(28). Of interest, however, when we presented the images to actual women, they preferred a male body much closer to that of an average man, with little added muscle

(27,

28).

Discussion

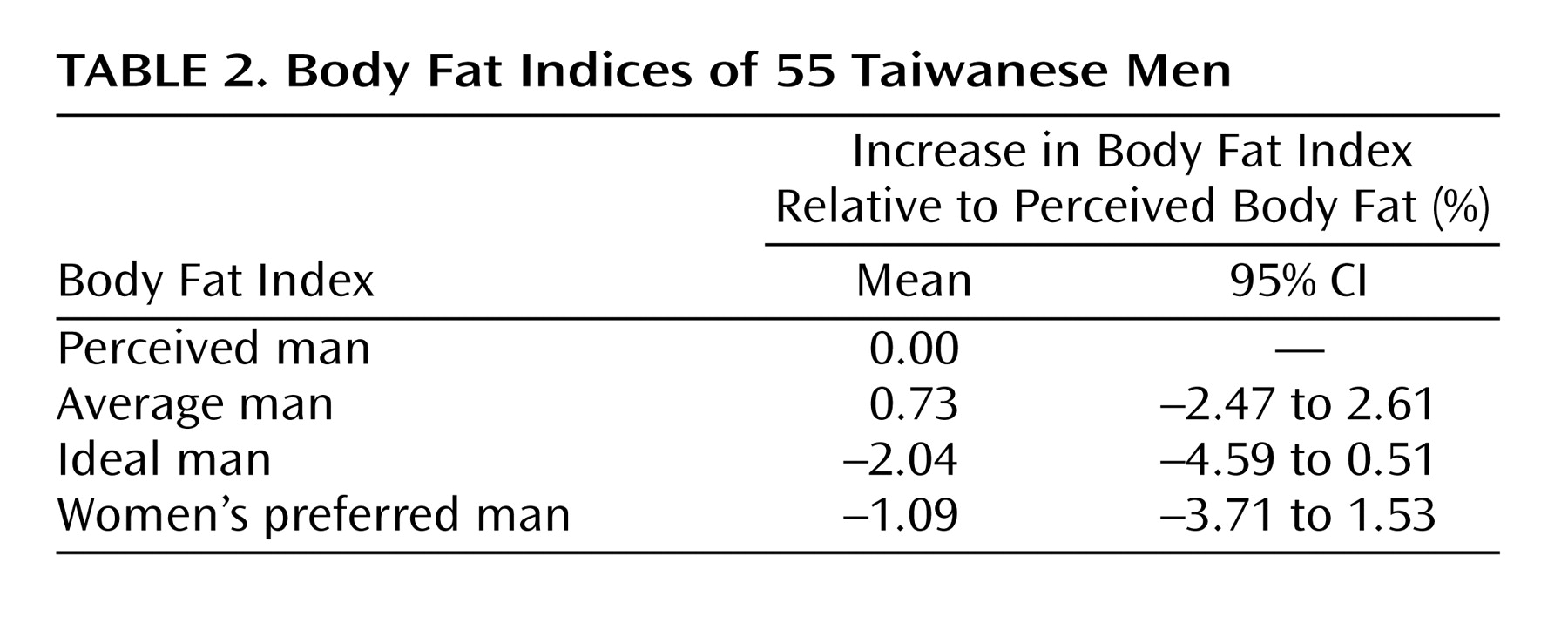

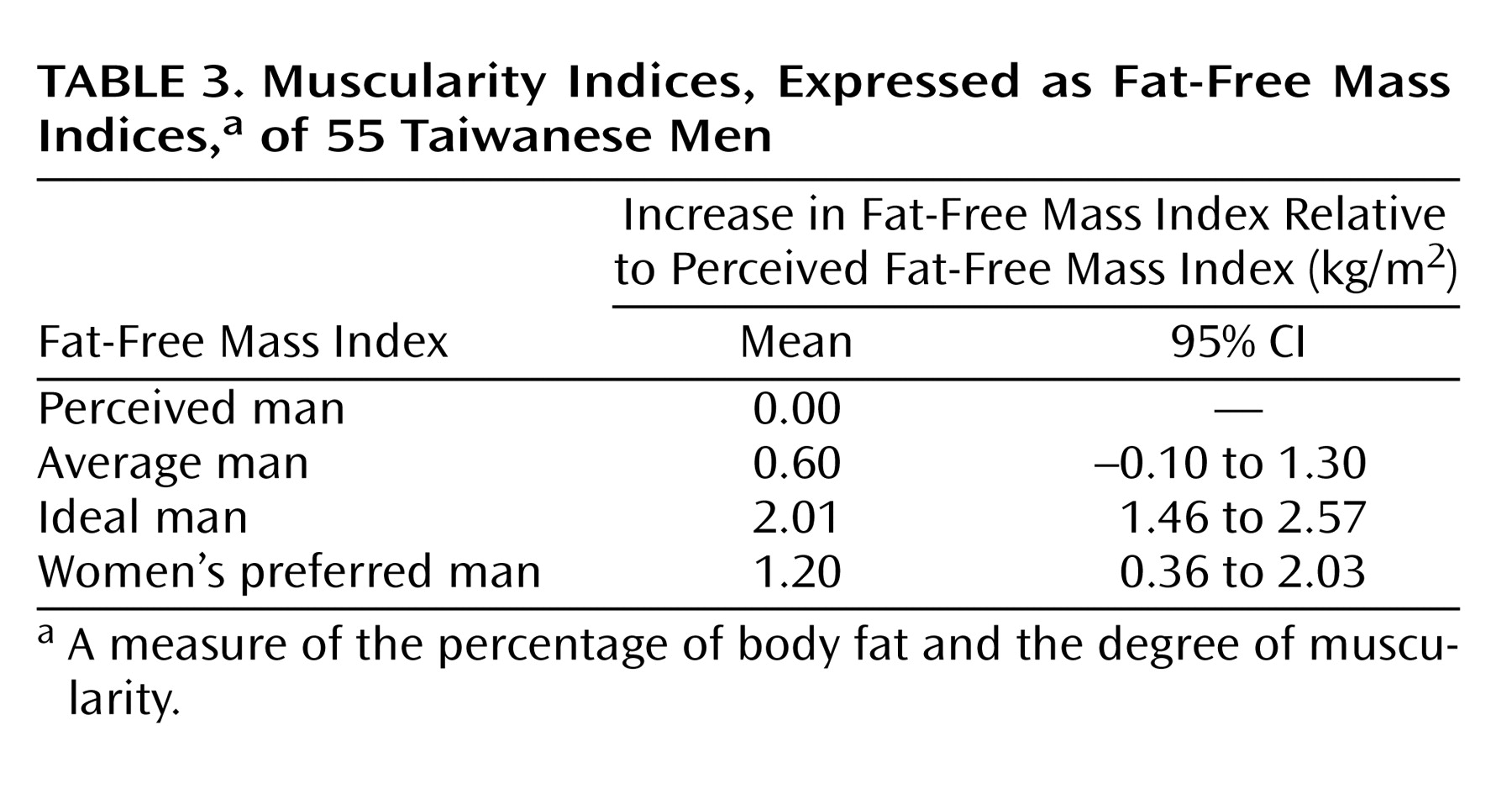

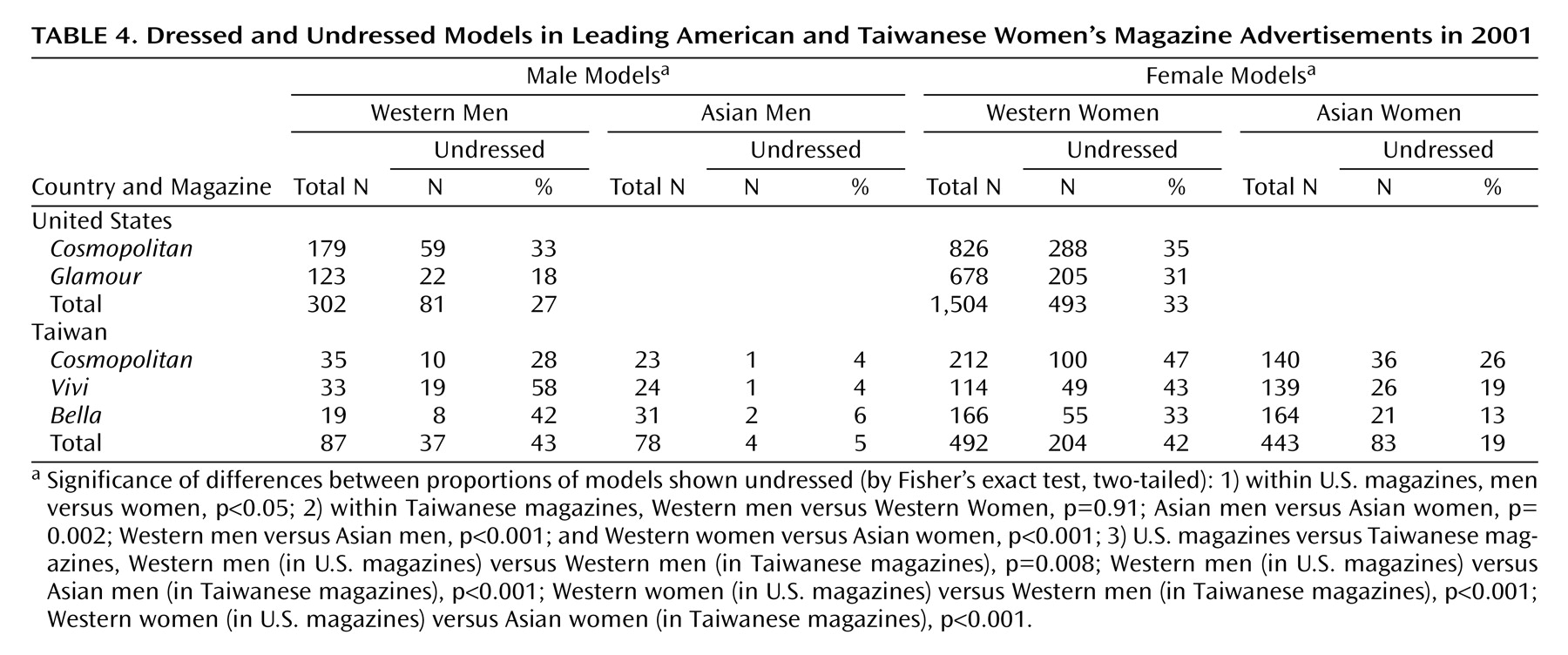

Body image disorders and anabolic steroid use appear to be much less prevalent among Asian men than among men in the United States or other Western societies. Based on this observation, we hypothesized that Chinese men in Taiwan would display less body dissatisfaction than Western men and that Taiwanese media advertising would place less “value” on the male body than Western media advertising. These two studies offer tentative support for these predictions. In study I, Taiwanese men estimated only a 5-lb difference between the muscularity of an average man and the male body that women prefer. By contrast, European and American men estimated this same difference to be about 20 lb. In study II, Taiwanese magazine advertisements portrayed nearly half of Western men and women in a state of undress, but Asian men were shown undressed in only 5% of cases. This observation suggests that, at least in the judgment of advertisers, body appearance (at least in terms of muscularity) is not a prime criterion for defining a Chinese man as masculine, admirable, or desirable, whereas the body has greater importance in defining an American man in these ways.

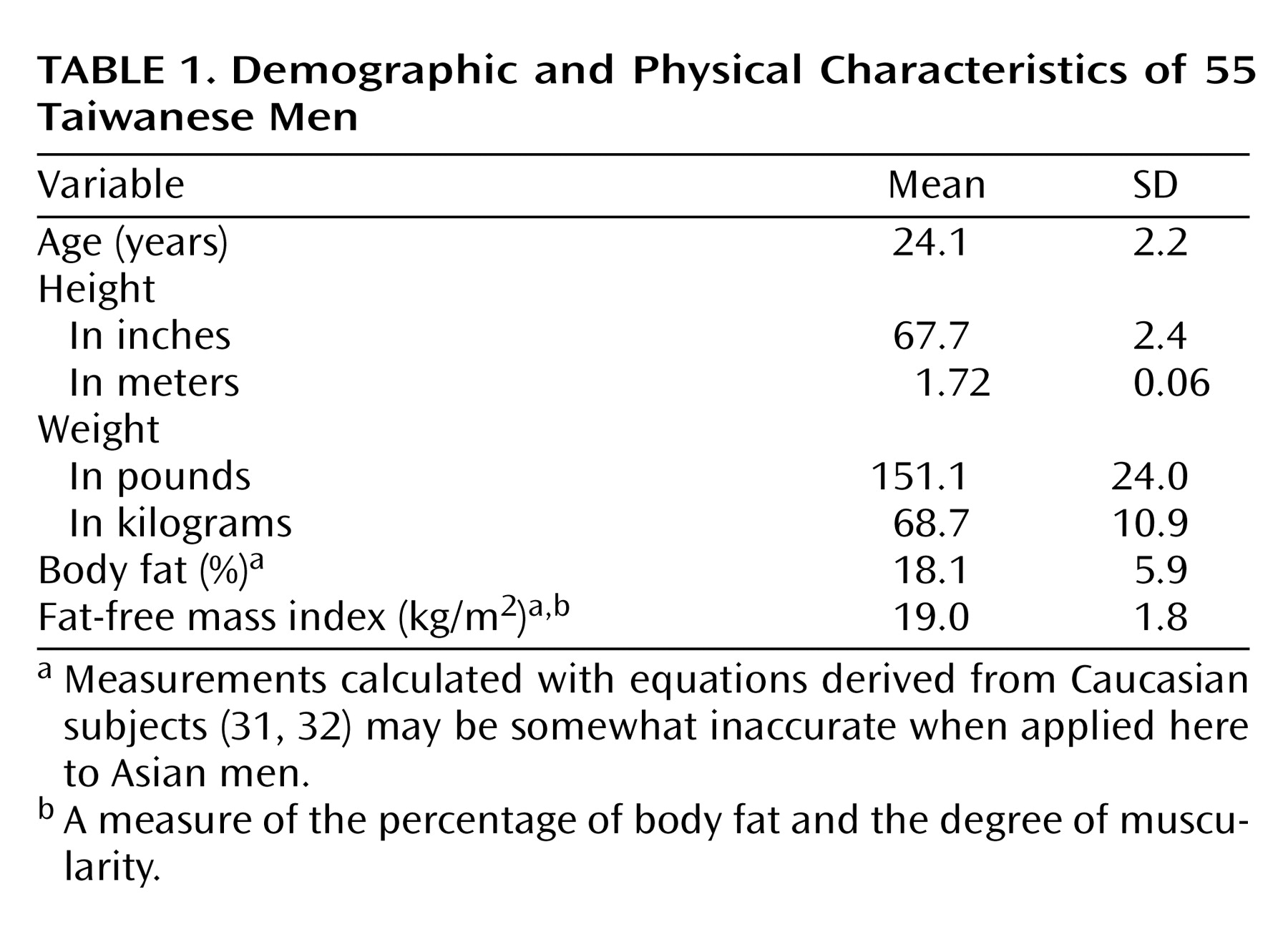

These studies are subject to various limitations. In particular, study I used a computerized test designed using Caucasian models. This technique might have introduced error when the instrument was administered to Asian subjects. We attempted to minimize this limitation, however, by focusing only on comparisons among the images chosen by the subjects on the computer rather than using the actual body measurements of the subjects themselves. Since any error introduced by the Caucasian images would likely apply similarly across all images, we believe that this error did not seriously bias our comparisons among images chosen by the subjects.

A limitation of study II is that advertisements in women’s magazines provide only an approximate measure of the value of bodily appearance relative to other features that define masculinity or desirability among men. We chose to use advertisements in women’s magazines as opposed to advertisements in men’s magazines, general magazines, or other advertising media, primarily because we had already published comparable data from American women’s magazines

(30) and could readily use these data for comparison with Taiwan. In short, we were using women’s magazine advertisements simply as a device to compare the cultural “value” of the male body in Taiwan versus the United States and not as an index of what men themselves prefer. Of course, the judgments of companies advertising Western and Asian products may not parallel the opinions of society as a whole, but advertisements are measured by their financial success and presumably optimized for a Taiwanese readership. Thus, it would seem unlikely that advertisers would stray very far from societal values and still remain in business. In light of these considerations and given the difficulty of designing and validating a definitive

direct assessment of the value of the male body, advertising data may offer a suitable proxy.

Given these limitations, our studies must be regarded as preliminary. Nevertheless, the two studies combine to suggest that American culture, and perhaps other Western cultures, have become much more focused on male body appearance than Chinese culture (we use the term “Chinese culture” here because 98% of the Taiwanese population is descended from China, and the traditional cultural values of this majority derive almost exclusively from Chinese traditions

[37]). What accounts for this difference? We propose three hypotheses: 1) Chinese culture places less emphasis on muscularity as a measure of masculinity, 2) Chinese men are less exposed to the muscular images common in American media, and 3) Chinese men have experienced less decline in their traditional male roles as “head of the household” than men in the United States and other Western countries.

We examine the first of these hypotheses: Western societies since antiquity have seen fitness and muscularity as a measure of masculinity, as illustrated by Greek and Roman statues or the heroes of mythology

(1,

38). The same emphasis on male athleticism and fitness extends from the Olympic competitions of Greece to the playing fields of English schools in the 19th century to muscular figures in early Hollywood westerns and to early American fitness magazines, such as

Your Physique and

Superman in the 1940s and 1950s

(39,

40). By contrast, we find no comparable historical focus on male muscularity in China. Although there is a “macho” tradition in China, it is the softer, cerebral male tradition that is dominant

(41). In the Chinese tradition, masculinity is comprised of both

wen

(translated as “mental” or “civil” and having core meanings centering around literary and cultural attainment) and

wu

(“physical” or “martial” and having core meanings of martial, military, force, and power)

(41,

42). It is

wen masculinity, however, that has been more highly regarded

(41–

44). For example, for most of the past two millennia, Chinese men have aspired to the Confucian ideal of the

Junzi

(gentleman, refined man, or virtuous man); in his

Analects, Confucius closely associated

Junzi with

wen but not with

wu (41,

45). Among traditional Chinese heroes and in modern Chinese literature, the cerebral male model of masculinity tends to dominate that of the macho, brawny type

(41,

43). In recent Chinese books and films, masculine qualities include free-spiritedness, independence in thinking, courage, mental strength,

da ye

attitude (cocky, self-assured),

zazhong gaoliang

(suffering from knowledge of one’s unworthiness, or, in other words, humility), and the ability to harness

qi  (46

(46,

47). And while physical appearance does carry weight in Chinese culture, the traditional Chinese notion of

Yanggang Zhiqi

(the ideal or essence of masculinity), as illustrated by these examples, does not emphasize muscularity.

A second possible factor, which may have further widened these differences between Western and Chinese attitudes, is the influence of media images, perhaps especially in the American media

(1). Widespread use of anabolic steroids in the last few decades has made it easy for male athletes, actors, and models to become leaner and more muscular than men without such chemical assistance in the past; images of these steroid-enhanced men are now common in magazines, television, and motion pictures. In addition, growing industries targeting men’s appearance regularly use such images in advertising. Preliminary data suggest that exposure to such images may cause young men to become dissatisfied with their bodies

(1,

48). Taiwanese men appear to be much less exposed to muscular images than American men. For example, in the United States, men’s “health” and fitness magazines, filled with images of muscular male bodies, are ubiquitous at supermarket counters and newsstands

(1,

38). In Taiwan, by contrast, there are no magazines resembling, for example, the American magazine

Men’s Health (49; Kingstone Bookstore, personal communication, 2003). It is also our anecdotal observation that Taiwanese television hardly ever shows images of muscular male bodies.

A third hypothesis is that American and Chinese cultures differ in the importance of traditional male roles and that this difference in turn may have influenced attitudes toward body image. In the United States and most other Western societies, the man’s traditional roles as breadwinner, soldier, and defender of the family have declined markedly over the last generation

(1,

50–52). Therefore, as we and others have suggested

(1), young Western men may have increasingly focused on their bodies as one of their few remaining sources of masculine self-esteem. By contrast, the traditional male role of “head of the household” remains more intact in Chinese culture than in the West

(53–

58). For example, until 1997, custody of children was automatically granted to the husband in the case of a divorce, and women (if married before 1985) could not have actual ownership of property in their own names

(57). A report also found that Taiwanese women worked on household chores 5.2 to 8.8 times as long as men compared to a ratio of less than 2 in the United States, Britain, and Canada

(57). Indeed, the notion of

zhongnan qingnu

(“men are superior, women inferior”)—a concept influenced by Confucian and Neo-Confucian traditions and the patrilocal clan system (with such characteristics as patriarchy, patrilocal residence, and patrilineality)—remains strong in Taiwan

(45,

57–61).

These three hypothesized differences between Western and Chinese culture—the first long-standing and the others recent—may explain the striking contrast between the findings of our two studies in Taiwan and the findings of our previous identical studies in the United States and Europe. These cultural differences in attitudes toward male body image have direct consequences for public health in that they may explain the far greater prevalence and severity of male body image disorders and of anabolic steroid abuse in the United States and other Western countries.

A disturbing question remains: Can Chinese attitudes continue to resist the influences of Western culture? When we looked at analogous studies of female body image, the prognosis was not encouraging. A study found that women in Hong Kong typically wanted to be thinner even though they were not overweight

(62). The authors concluded that a “typically ‘Western’ pattern of body dissatisfaction has overshadowed traditional Chinese notions of female beauty”

(62, p. 77). Similarly, studies in Polynesia

(63,

64) have found that women who were formerly content with their bodies have recently succumbed to Western ideals of thinness; for example, a prospective investigation in Fiji found striking changes in adolescent girls’ body satisfaction after only 3 years of exposure to Western television

(64). These observations raise the prospect that Western notions of male body image may also be invading Chinese culture, leading to a noticeable increase in muscle dysmorphia, other body image disorders, and anabolic steroid abuse among young Chinese men in the near future. To test for this possibility, it might be useful to study body image among Taiwanese men after another 5–10 years.

(translated as “mental” or “civil” and having core meanings centering around literary and cultural attainment) and wu

(translated as “mental” or “civil” and having core meanings centering around literary and cultural attainment) and wu  (“physical” or “martial” and having core meanings of martial, military, force, and power) (41, 42). It is wen masculinity, however, that has been more highly regarded (41–44). For example, for most of the past two millennia, Chinese men have aspired to the Confucian ideal of the Junzi

(“physical” or “martial” and having core meanings of martial, military, force, and power) (41, 42). It is wen masculinity, however, that has been more highly regarded (41–44). For example, for most of the past two millennia, Chinese men have aspired to the Confucian ideal of the Junzi  (gentleman, refined man, or virtuous man); in his Analects, Confucius closely associated Junzi with wen but not with wu (41, 45). Among traditional Chinese heroes and in modern Chinese literature, the cerebral male model of masculinity tends to dominate that of the macho, brawny type (41, 43). In recent Chinese books and films, masculine qualities include free-spiritedness, independence in thinking, courage, mental strength, da ye

(gentleman, refined man, or virtuous man); in his Analects, Confucius closely associated Junzi with wen but not with wu (41, 45). Among traditional Chinese heroes and in modern Chinese literature, the cerebral male model of masculinity tends to dominate that of the macho, brawny type (41, 43). In recent Chinese books and films, masculine qualities include free-spiritedness, independence in thinking, courage, mental strength, da ye  attitude (cocky, self-assured), zazhong gaoliang

attitude (cocky, self-assured), zazhong gaoliang  (suffering from knowledge of one’s unworthiness, or, in other words, humility), and the ability to harness qi

(suffering from knowledge of one’s unworthiness, or, in other words, humility), and the ability to harness qi  (46, 47). And while physical appearance does carry weight in Chinese culture, the traditional Chinese notion of Yanggang Zhiqi

(46, 47). And while physical appearance does carry weight in Chinese culture, the traditional Chinese notion of Yanggang Zhiqi  (the ideal or essence of masculinity), as illustrated by these examples, does not emphasize muscularity.

(the ideal or essence of masculinity), as illustrated by these examples, does not emphasize muscularity. (“men are superior, women inferior”)—a concept influenced by Confucian and Neo-Confucian traditions and the patrilocal clan system (with such characteristics as patriarchy, patrilocal residence, and patrilineality)—remains strong in Taiwan (45, 57–61).

(“men are superior, women inferior”)—a concept influenced by Confucian and Neo-Confucian traditions and the patrilocal clan system (with such characteristics as patriarchy, patrilocal residence, and patrilineality)—remains strong in Taiwan (45, 57–61).