A number of studies have reported high rates of borderline personality disorder or features in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

(1–

4). There are several possible explanations for these high rates. First, preexisting features of borderline personality disorder may serve as a risk factor for the development of PTSD. Gunderson and Sabo

(5) suggest that individuals with borderline personality disorder have limited resources for dealing with traumatic events, which leaves them more vulnerable toward developing PTSD. Second, it may be that trauma, in and of itself, causes enduring changes in character. This explanation is consistent with a large body of evidence showing high rates of childhood trauma in adults with borderline personality disorder

(6–

9). In fact, Herman and van der Kolk

(10) view borderline personality disorder, like PTSD, as a stress-related disorder. Third, it could be that borderline features develop in response to living with the core symptoms of PTSD rather than to trauma per se

(1). For example, nightmares and sleep deprivation can lead to irritability, intense anger, and affective instability—symptoms commonly associated with borderline personality disorder.

The present report is part of a follow-along investigation focusing on the evolution of trauma-related symptoms in veterans of Operation Desert Storm. Desert Storm veterans recruited from Connecticut National Guard units filled out self-administered questionnaires at multiple time points after their return from the Gulf. The goal of the current report was to examine the relationship among the severity of war-related trauma, symptoms of PTSD, and borderline personality disorder features in veterans of Desert Storm.

This report uses a mixed retrospective/prospective design to address some of the limitations of prior research. Pretrauma borderline personality disorder features were assessed retrospectively and used to predict postwar PTSD symptoms, and PTSD symptoms measured shortly after return from the Gulf were used to predict subsequent borderline personality disorder features. The study hypotheses were as follows:

Discussion

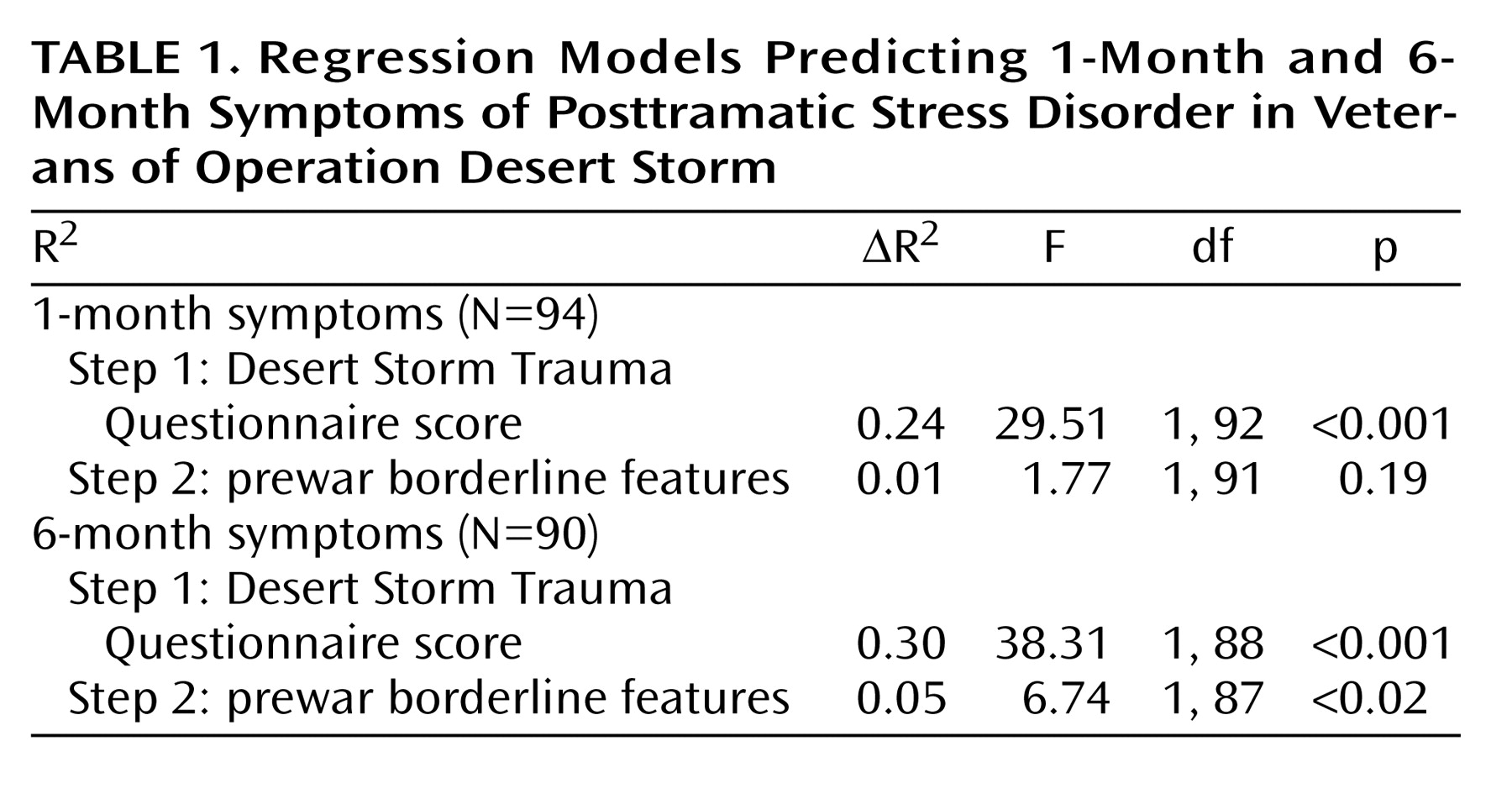

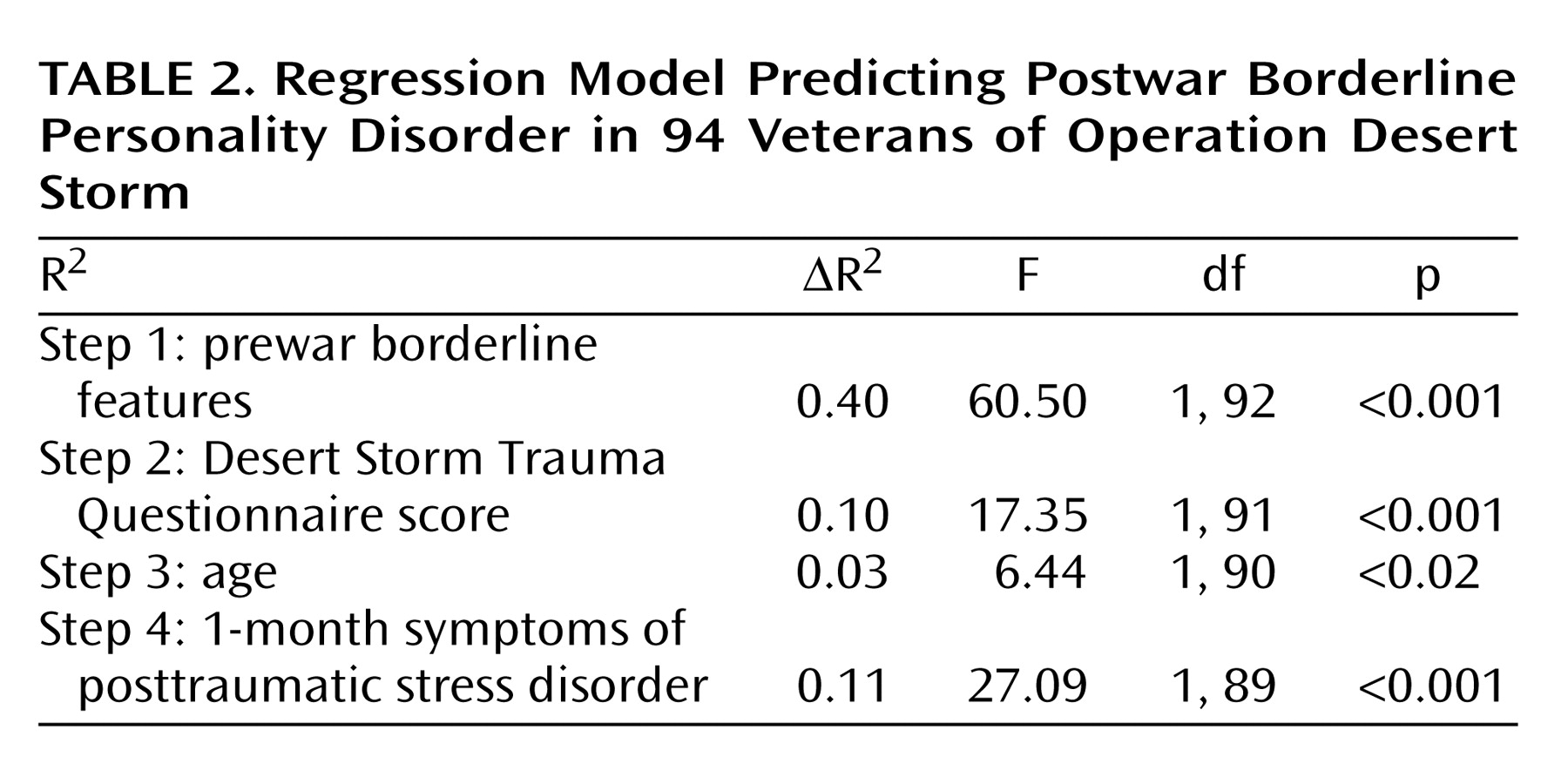

In the present report on Operation Desert Storm veterans, prewar features of borderline personality disorder predicted variability in postwar PTSD symptoms beyond that predicted by combat exposure, combat exposure predicted variability in postwar features of borderline personality disorder, and PTSD severity assessed shortly after combat exposure accounted for additional variability in subsequent features of borderline personality disorder. The findings support each of the three study hypotheses and point to a complex relationship among trauma, PTSD symptoms, and borderline personality disorder features.

Prewar borderline personality disorder features accounted for a significant amount of variance in PTSD symptoms at 6 months postwar (5%) but did not significantly account for PTSD symptoms at 1 month postwar. The finding with regard to 6-month PTSD is consistent with Gunderson and Sabo’s suggestion

(5) that individuals with borderline personality lack adequate coping mechanisms and are therefore vulnerable to posttraumatic stress reactions after trauma. It is also possible that individuals with borderline personality disorder features, such as dangerous impulsivity and uncontrolled anger, are more likely to engage in situations where they are exposed to trauma, putting them at increased risk for developing PTSD. However, our data did not find a significant correlation between prewar borderline personality disorder features and combat exposure (r=0.12, p=0.26). Other personality features that have been reported as risk factors for the development of PTSD include neuroticism, extraversion, external locus of control, and poor self-esteem

(23,

24). Neuroticism, external locus of control, and poor self-esteem share variability with borderline personality disorder features, but extraversion does not

(25). Additional research may identify other personality disorder traits that create a vulnerability to PTSD.

The second hypothesis was supported in that level of Desert Storm trauma exposure accounted for 10% of the variability in postwar borderline personality disorder features beyond the variability accounted for by prewar borderline personality disorder features. Exposure to early life trauma, such as childhood physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, has long been considered a risk factor for the development of borderline personality and has been supported by prospective research

(13,

14). However, traumatic exposure during late adolescence and early adulthood has not typically been associated with symptoms of this disorder.

The third hypothesis was also supported because PTSD symptoms at 1 month accounted for 11% of the variability in borderline personality disorder features at 6 months above and beyond the contributions from prewar borderline personality disorder features, war trauma (Desert Storm Trauma Questionnaire score), and age. Herman

(15) has suggested that the DSM-IV “simple” PTSD symptoms of intrusiveness, avoidance, and hyperarousal are typical stress responses to acute traumatic experiences but that when individuals experience prolonged or repeated trauma, they also develop “complex PTSD” responses (also called disorders of extreme stress not otherwise specified), including borderline personality disorder-like symptoms. She described the nature of prolonged stress, such as being subjugated to coercion, and the adjustments that individuals make that result in complex PTSD symptoms. Our data indicate that the development of “simple” PTSD symptoms in and of themselves may create challenges that require personality adjustments. “Simple” PTSD symptoms, such as hypervigilance to cues, emotional detachment, and chronically disturbed sleep, are often highly disruptive and debilitating. Living with these symptoms may lead to a number of experiences commonly associated with borderline personality disorder, including marked affective instability, unstable and intense interpersonal relationships, and inappropriate intense anger. We believe that living with “simple” PTSD symptoms provides an additional component to the etiology of complex PTSD, as described by Herman

(15).

The current findings suggest that adulthood traumatic experiences and posttraumatic stress sequela may contribute to the development of borderline personality disorder features. The onset of borderline personality disorder symptoms in adulthood is consistent with two diagnostic categories that were considered for the DSM-IV but not included. In addition to complex PTSD/disorders of extreme stress not otherwise specified, which was ultimately added to the associated features text of DSM-IV PTSD

(26,

27), the ICD-10 diagnosis of enduring personality change after catastrophic experience was considered for DSM-IV inclusion

(28). If the current findings are extended by additional research linking adult trauma exposure to borderline personality disorder-like personality changes that cause clinically significant distress or impairment, then further consideration should be given to adding these trauma-related diagnostic categories to DSM-V.

Common neurobiological features related to affect dysregulation, impulsivity, and stress reactivity may contribute to the high rate of co-occurrence of borderline personality disorder and PTSD. Examples of this shared pathophysiology include decreased platelet α

2-adrenergic receptor number

(29,

30), hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis hyperresponsivity to pharmacologic challenge

(31,

32), elevated CSF corticotrophin-releasing hormone

(33,

34), reduced hippocampal volume

(35,

36), and exaggerated amygdala activation in response to stressful stimuli

(37,

38). Of course, further research will be necessary to identify potential relationships among neurobiological alterations, symptom development, and the possible direction of influence between borderline personality disorder and PTSD.

There are a number of limitations in the current study. First, participants were non-treatment-seeking and did not exhibit high rates of psychopathology

(18). Therefore, the relationships among trauma, PTSD symptoms, and borderline personality disorder features may not replicate with treatment-seeking patients. On the other hand, given the low rates of pathology, it is unlikely that the self-reports of these participants would have been compromised by disability or compensation claims, and in fact, we were unaware of any participants pursuing such claims, and no participants requested to have study assessments released for such purposes. Also, given that the study hypotheses were supported within the restricted range of pathology of this sample, it would be reasonable to expect the relationships to be maintained in samples with greater variability. Future prospective investigations with larger military samples are necessary to examine these relationships in participants that develop full PTSD and/or borderline personality disorder conditions.

Second, the current data are limited to self-report measures of combat trauma, PTSD symptoms, and borderline personality disorder features. Objective measurement of combat experience is not available to assess the criterion validity of the Desert Storm Trauma Questionnaire self-report, and there is some indication that self-reported accounts of combat exposure are not perfectly reliable. In a previous study that used many of the same participants from the current study

(39), we found that self-reported accounts of combat exposure did not remain perfectly consistent across time, particularly when attending to responses on individual exposure items. However, the participants’ total number of types of exposure (or Desert Storm Trauma Questionnaire total scores) was fairly consistent, changing on average by less then one type of exposure

(39). The present analyses relied upon Desert Storm Trauma Questionnaire total scores and are therefore not likely to have been significantly affected by inconsistent reporting of combat exposure.

Third, the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire scales have demonstrated low diagnostic thresholds, thus overdiagnosing personality disorders

(22). Therefore, it would not be appropriate to use the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire to estimate rates of borderline personality disorder in this group. However, low diagnostic thresholds are advantageous for examining dimensional relationships of personality disorder features in healthy samples because more stringent criteria would not yield sufficient variability for use in a nonclinical sample.

Fourth, prewar and postwar borderline personality disorder features, as measured by Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire items, correlated at 0.62. Had these measures been given prospectively, a correlation of this magnitude might have suggested only modest test-retest reliability. However, each Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire item was completed by the participants for the two intervals at the same time (literally marked on the same page), indicating that any difference in scores was a deliberate reflection of the participants’ change in self-perception between the two intervals and not due to a lack of reliability in the self-report measure. On the other hand, the retrospective account of prewar personality functioning is a significant limitation of this data. It will be important to conduct prospective assessments of prewar and postwar personality functioning in future investigations, although such investigations will obviously require significant resources.

Finally, given the nature of the military strategies employed in Operation Desert Storm (i.e., strong reliance on missiles and air assaults and limited ground confrontation), it might be presumed that the degree of combat exposure would have been insufficient to result in posttraumatic stress reactions. Nonetheless, most participants were confronted with multiple combat-related stressors. Participants in this study were frequently exposed to incoming SCUD missile attacks, and some participants were reportedly stationed as guards at the entrance to their compound and were prevented from taking refuge in bunkers during missile attacks. In addition, some soldiers were exposed to enemy small-arms fire (many participants from one unit witnessed the deaths of a physician and a nurse), and several participants reported seeing burned and charred bodies and flattened corpses.

The findings of this study have a number of potential implications. First, for individuals choosing or hiring for professions that involve a high risk of becoming traumatized, such as military or law enforcement, it is important to consider that features of personality may serve as potential risk factors for developing PTSD. Second, when diagnosing borderline personality disorder features in adulthood, clinicians should consider the contribution of adulthood trauma as well as childhood trauma. Further, when one is treating traumatized individuals with PTSD and comorbid features of borderline personality disorder, lessening the symptoms of PTSD may, over time, help to reduce coexisting borderline personality disorder features. Alternatively, targeting borderline personality disorder-related problems, such as affective dysregulation and impulsivity (e.g., reference

40), might be necessary before patients will be able to fully benefit from treatments focused on resolving PTSD symptoms (e.g., reference

41). Finally, the presence of personality disorder features can alter the way in which PTSD patients are viewed and/or treated by clinicians, researchers, and disability claim adjusters. For example, patients with symptoms of borderline personality disorder may be avoided or labeled as problematic, and traumatized individuals may be denied disability claims, despite the fact that trauma appears to contribute to borderline personality disorder features, as well as PTSD.

Taken together, the present findings suggest that trauma, symptoms of PTSD, and features of borderline personality disorder are related to one another in a complex fashion that may exceed simple linear models. The features of borderline personality disorder appear to be both a risk factor for the development of PTSD symptoms and a potential consequence of living with PTSD symptoms. In addition, it appears that trauma can contribute to changes in personality, even in adulthood. Future prospective investigations are necessary to clarify the role of military trauma and other adult traumas in the development of borderline personality disorder symptoms in adulthood. Longitudinal investigations may reveal a positive feedback loop between PTSD symptoms and borderline personality disorder features that helps to maintain both conditions over time.