The past two decades have witnessed growing attention to the interplay between physical and psychological injuries, i.e., to the psychological consequences of physical injury

caused by a traumatic event

(1). Traditional views, particularly psychoanalytic ones, tended to regard bodily injury as a protective factor against the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

(2). At the basis of this belief was the assumption that physical injury absorbs much of one’s “free-floating psychic energy,” thus reducing the chance of developing anxious or conflicting feelings about the traumatic event. In addition, unlike psychological wounds, bodily injuries typically engender more sympathy from the environment. And finally, a physical wound often removes the source of anxiety by providing an escape from the stressful situation, especially in combat conditions. In support of this view, Merbaum and Hefez

(3) found that wounded soldiers (representing the full range of injury severity) showed minimal, if any, psychological disturbances.

However, over the past two decades numerous studies of injured trauma survivors have challenged these traditional understandings of the relationship between PTSD and injury. First, studies in wounded Vietnam veterans have found two- to threefold higher rates of PTSD among this population than among those who returned unharmed

(4,

5). Second, multiple studies have found moderate to high rates of PTSD among injured survivors of other types of traumatic events, such as traffic accidents

(6–

9), terrorism

(10), criminal assault

(11), and burn injuries

(12). The prevalence rates of PTSD in these samples varied from 11% to 40%

(8,

9,

12). Similar rates of PTSD have also been observed in mildly injured brain trauma survivors

(13). Finally, while a few studies have shown that risk for PTSD is associated with severity of injury

(14), other studies have failed to replicate these results

(5,

15).

Thus, despite the marked variability in the reported rates of PTSD among injured populations, the rapidly growing literature on this topic suggests that traumatic injury not only does not reduce the risk for PTSD, as believed by traditional psychoanalytic views, but may even increase it. Yet, while considerably contributing to our understanding of the risk-elevating nature of injury with regard to PTSD, the increasing body of literature reveals relatively little about the unique contribution of bodily injury, over and above that of the trauma itself, to the subsequent development of PTSD. The reason is that no study directly compared, in a matched, case-control design, injured and noninjured survivors of the same trauma.

The aim of the present study was to estimate the unique contribution of physical injury, over and above that of the trauma itself, to the subsequent development of PTSD. More specifically, our goals were to 1) replicate previous findings regarding higher than average rates of PTSD in injured survivors of combative actions and 2) evaluate the relationship of PTSD symptoms with both the nature and severity aspects of the injury. To accomplish these goals, we employed an event-based, matched design in a group of injured and noninjured soldiers who experienced the same traumatic combat event.

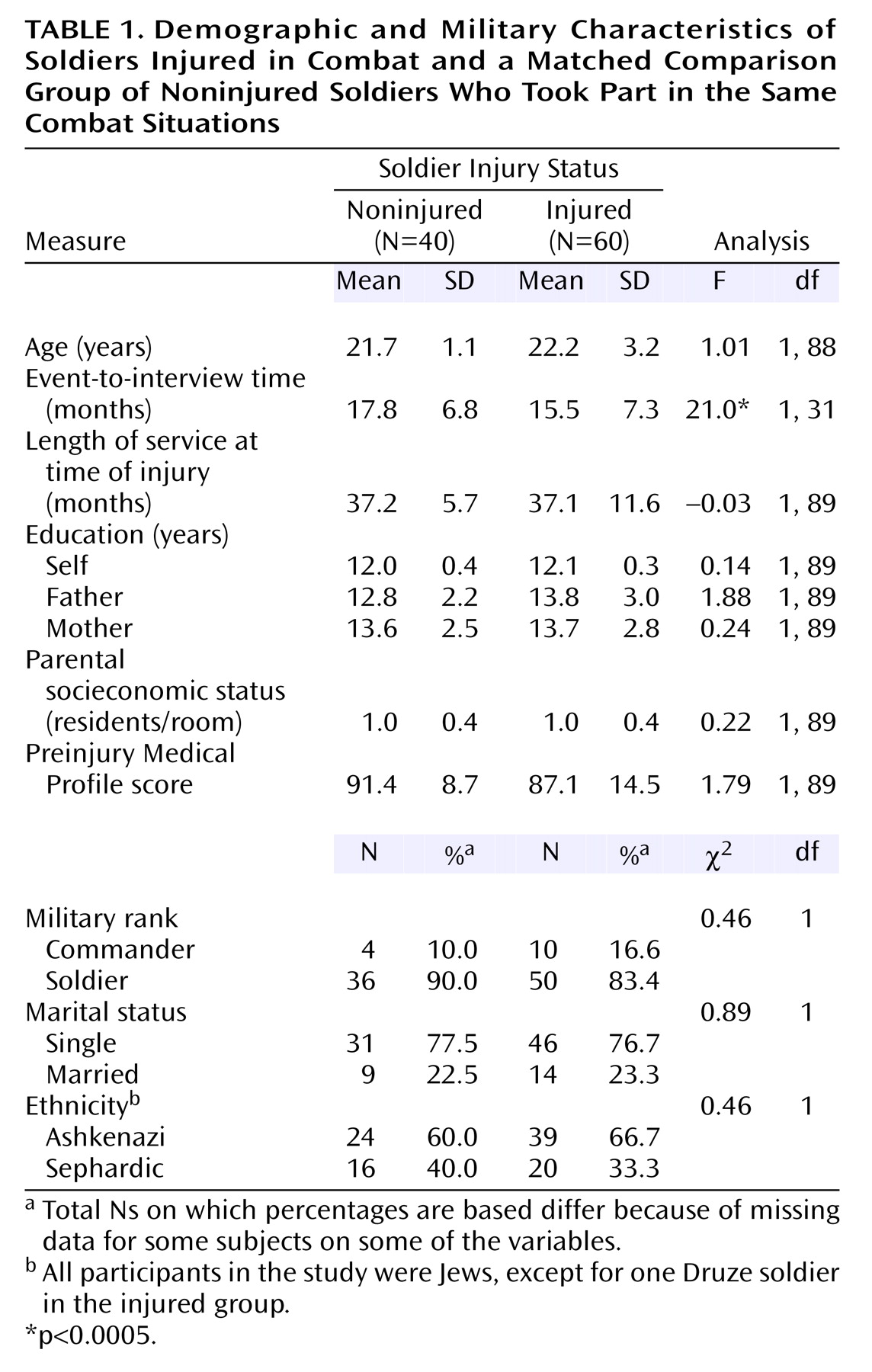

Results

Prevalence of PTSD

According to the SCID, 10 (16.7%) of the 60 injured survivors, but only one (2.5%) of the 40 comparison participants, met diagnostic criteria for PTSD at the time of the interview (since trauma is typically not single in combat, it is worth noting that the event that caused the injury was the major traumatic event in all cases with PTSD). Another three (5.0%) of the 60 injured soldiers, but none of the comparison noninjured soldiers, reached a subthreshold level of PTSD (i.e., diagnostic criteria were met for two of the three DSM core posttraumatic clusters). The difference in the prevalence of PTSD between the two groups was statistically significant (odds ratio=8.6, 95% CI=1.1–394.3; p<0.04). Comparison of respondents with and without PTSD on background variables indicated that the two groups were highly homogeneous, with no statistically significant differences on any of the variables examined.

In addition to PTSD, participants were also assessed for other current and lifetime major axis I diagnoses. Of the 60 injured soldiers, two met DSM-IV criteria for current major depression, one for bipolar depression, two for adjustment disorder with depressive mood, and another two for substance use disorder. Of the 40 noninjured soldiers, one met diagnostic criteria for major depression and another one for adjustment disorder with depressive mood. In all cases, the onset of these comorbid diagnoses was after the traumatic event. While presence of any of these diagnoses was not significantly related to injury, there was a significantly greater likelihood that soldiers with PTSD would also suffer from a mood-related disorder (36.4%) than those without PTSD (3.4%) (p=0.008, Fisher’s exact test).

Psychiatric Symptom Severity

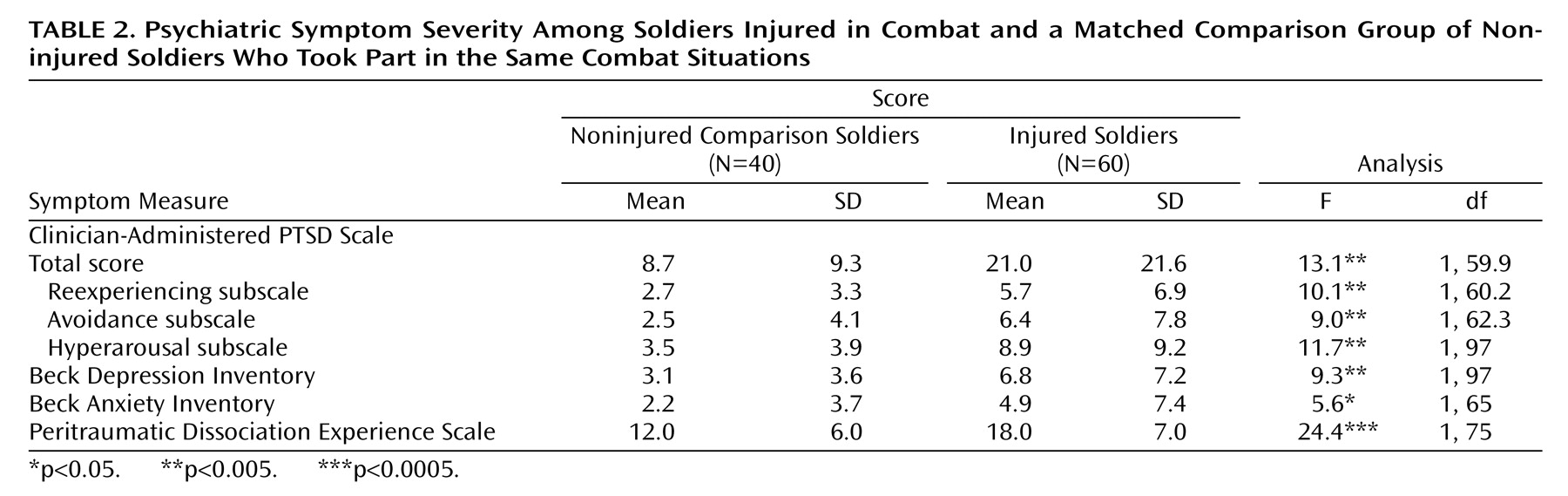

In this step, rather than focusing on PTSD as a formal diagnosis, we compared the frequency and intensity of PTSD symptoms—as well as dissociation, anxiety, and depression symptoms—in the injured and noninjured groups (

Table 2). As can be seen, wounded participants, as a group, had significantly higher scores on all clinical scales than their noninjured comparison counterparts. With respect to the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale subscales, the direction and size of intergroup differences were generally consistent across all three PTSD cluster scores (i.e., reexperiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal), with a slightly larger effect on the hyperarousal subscale.

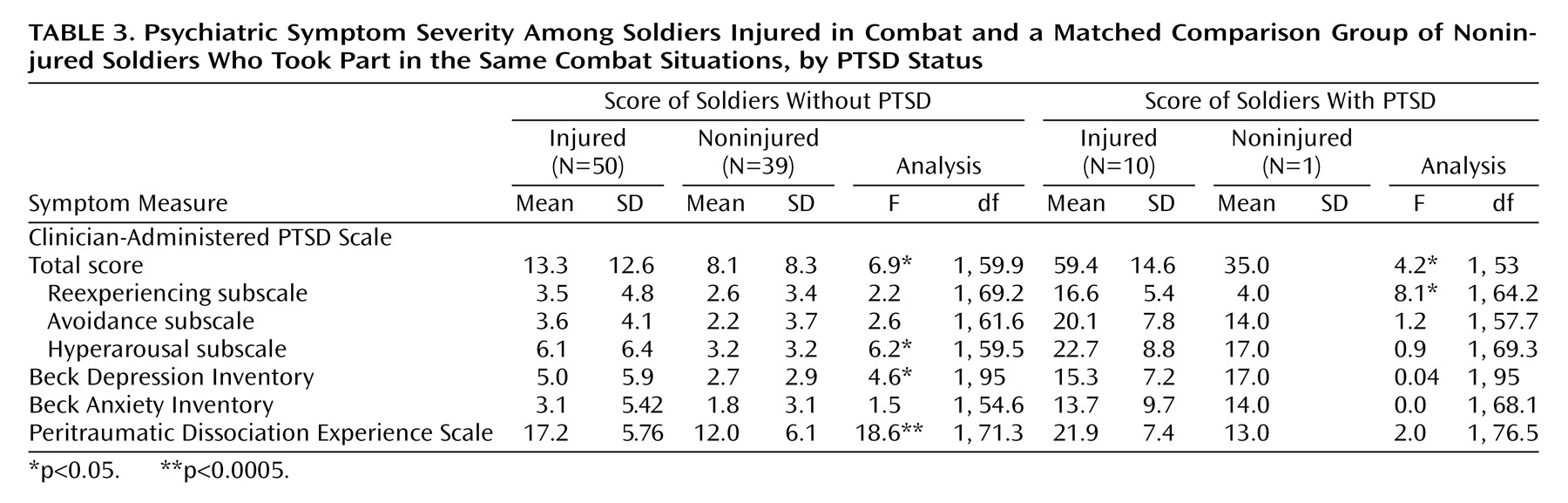

Next, in order to examine whether these intergroup differences could be explained solely on the basis of the larger number of participants with PTSD in the injured group, we retested the effect of injury on all clinical symptoms while controlling for PTSD status. That is, we tested the effect of injury twice: first only in those without PTSD and then only in those with PTSD (

Table 3). As can be seen, the effect of injury on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale total score remained significant regardless of PTSD status. Of interest though is that while score on the hyperarousal subscale appeared to contribute most to the effect of injury on the overall Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale score among those without PTSD, among those with PTSD it was score on the reexperiencing subscale. This suggests that injury elevates hyperarousal symptoms in all subjects, but has a special effect on reexperiencing symptoms among those who go on to develop PTSD. Finally,

Table 3 also reveals that injury has a significant effect on symptoms of both depression and peritraumatic dissociation in those without PTSD.

Severity of Trauma and Injury

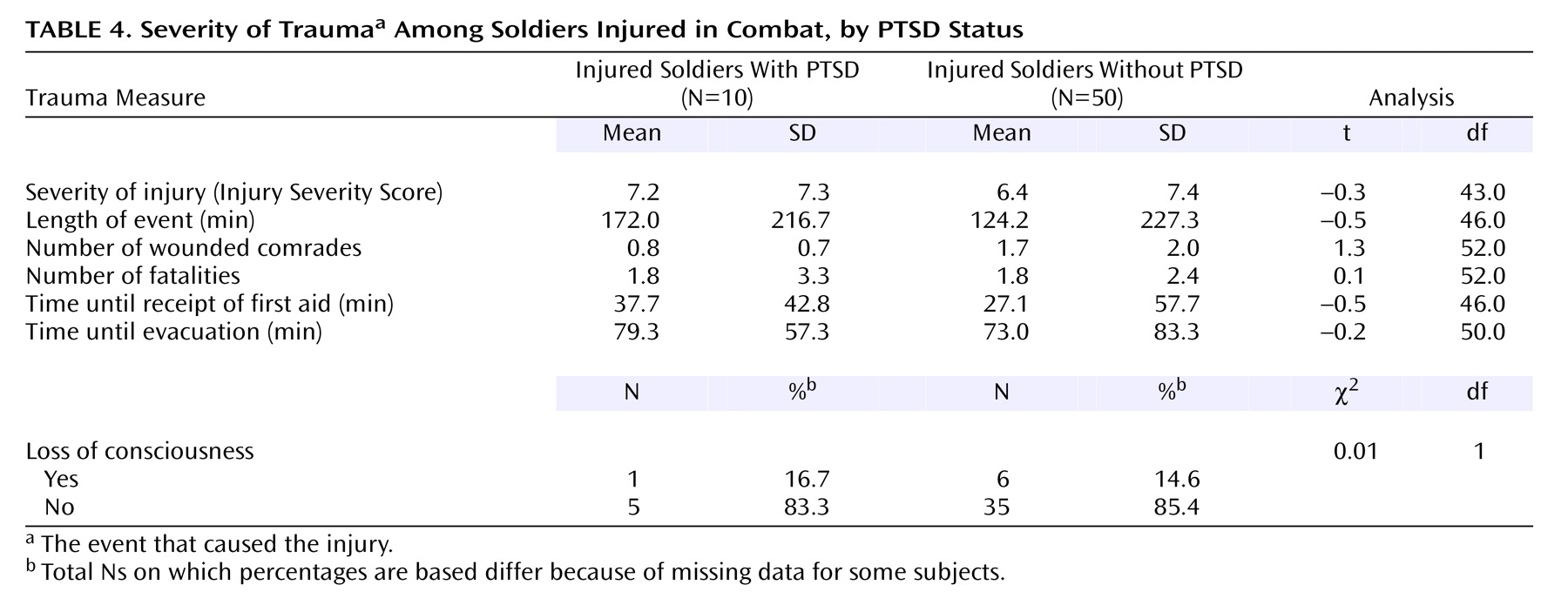

Next, we examined the potential mediating role of trauma severity as it affects the relationship between traumatic injury and further development of PTSD.

Table 4 presents potential indicators of the severity of the trauma (i.e., the event that caused the injury) among the injured soldiers with and without PTSD. As can be seen, a set of t tests for independent groups revealed no significant differences between participants with and without PTSD on any of these characteristics. It is particularly noteworthy that there was no difference between the two groups on severity of injury, as assessed by the Injury Severity Score. This finding was corroborated by the correlations of the Injury Severity Score with the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale subscale scores and its total score being all practically zero.

Last, we looked at the effect of physical injury on the co-occurrence of PTSD, depression, and anxiety symptoms. It is interesting that in the injured group, the correlations between PTSD symptoms and symptoms of anxiety (r=0.65, df=58, p<0.0001) and depression (r=0.75, df=58, p<0.0001) were remarkably higher than in the noninjured comparison group (r=–0.28 and r=–0.06, respectively). Moreover, a set of t tests revealed that the between-group differences for all pairs of corresponding correlations were also statistically significant (t=2.15–4.02, p<0.05).

Discussion

The current study attempted to isolate the unique contribution of bodily injury to the development of PTSD. To accomplish this goal we used an event-based, matched design. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that addresses this question utilizing such a powerful design. Consistent with most of the recent literature

(4,

14), our findings clearly indicate that bodily injury is a risk factor—rather than a protective one—for PTSD. Moreover, in addition to just advancing the robustness of this notion, the data also suggest that the odds of developing PTSD following traumatic injury are approximately eight times higher than following injury-free trauma. In fact, they suggest that even this rather high figure might be an underestimate. This is so because about 35% of the originally approached injured soldiers, but none of the noninjured comparison subjects, refused participation. From the explanations that these nonparticipants gave for their refusal, it was quite obvious that many of them did so for reasons that can be interpreted as avoidance.

It is interesting that while associated with higher levels of anxiety and depression symptoms, bodily injury in this study was not related to increased prevalence of comorbid psychiatric diagnoses. In contrast, psychiatric comorbidity was significantly related to presence or absence of PTSD. This finding is consistent with previous studies, including our own

(7), suggesting a strong association between PTSD and psychiatric comorbidity among injured trauma survivors. Taken together, our findings indicate that PTSD moderates psychiatric comorbidity following traumatic injury.

Our findings further suggest that bodily injury does not have a differential effect on any of the PTSD symptom domains. This finding was evident by the direction and size of differences, which were generally consistent across all three PTSD cluster scores. Such a finding is consistent with our previous results in a study with injured survivors of motor vehicle accidents

(7).

What other factors might explain the increased risk for PTSD associated with bodily injury? The most simple and straightforward hypothesis is that bodily injury increases the perceived threat to one’s life or physical integrity during the trauma. Indeed, according to the literature, the perceived level of danger by trauma survivors is a better predictor of PTSD than the actual severity of the traumatic event

(10). However, this explanation may be too simplistic because while strongly supporting the possibility that bodily injury contributes to the appraisal of the traumatic event as more dangerous, our data also suggest that this heightened level of perceived threat is not a simple, straightforward function of the severity of injury. This finding, which is consistent with previous studies

(5,

14), suggests that bodily injury exerts its effect on perceived threat via interaction with other factors, such as the effect that it has on one’s (perceived and real) ability to function and cope during the traumatic event.

Another potential mediating factor between physical injury and PTSD might be peritraumatic dissociation, which has been implicated as a risk factor for PTSD in previous studies

(24). This possibility was supported in our study by injured participants, with or without PTSD, reporting significantly higher levels of peritraumatic dissociation than their noninjured fellows. Furthermore, controlling for peritraumatic dissociation remarkably decreased the differences between the injured and noninjured groups on all the PTSD as well as the other clinical measures. While dissociation is commonly conceived of as a vulnerability factor in its impairing integration and reprocessing of the trauma, an interesting alternative possibility is that the relationship between bodily injury and dissociation might be reversed. That is, people who tend to dissociate under stress might be at higher risk for getting injured. Because of the post facto, retrospective nature of this study, such a possibility cannot be ruled out.

While not directly assessed in this study, there are also noteworthy biological mechanisms that may mediate between injury and PTSD. These hypothesized mechanisms relate to the complex interactions between the immune and stress-regulating systems, in particular the interaction between the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and proinflammatory mediators such as cytokines. In addition to its key role in the regulation of the stress response, the HPA axis is also involved in modulation of the immune response to inflammation and injury through proinflammatory mediators such as cytokines

(25). Since alterations in the HPA axis have been suggested as a vulnerability factor for PTSD

(26), situations that involve both emotional and injury-related stress may create an extra burden on an already compromised HPA axis. While this hypothesis has yet to be explored, numerous preclinical studies found that cytokines have adverse effects on memory, sleep, and mood

(27). Similarly, they promote sickness behavior

(27). Indeed, a previous study

(28) found elevated CSF concentrations of interleukin-6 in patients with PTSD versus normal comparison subjects.

Finally, the extent to which the current findings can be generalized to other populations is worth consideration. Overall, the rate of PTSD in our sample (10%) was generally in line with, although at the lower end of, previous estimates among soldiers involved in combat activity. However, prevalence of PTSD in the noninjured group was very low (2.5%). This may be explained by the nature of the participants in our study, who were soldiers in elite units who underwent extensive preinduction screening and a long and demanding course of basic training, which enables further selection and facilitates acquisition of habitual coping styles. In addition, these units are characterized by high levels of motivation and unit cohesion, which have been shown to be resilience factors against the development of PTSD

(29) as well as general mental health problems

(30). These factors suggest that generalizing from this study should be made with caution and call for further replication with a more heterogeneous and unscreened sample.

A few methodological issues that limit interpretation of the current findings are worth mentioning. First, PTSD symptoms were assessed relatively long after the traumatic injury. Thus, our data provide a reliable estimate of stable posttraumatic symptoms (which also minimizes concerns regarding potential effects of the slightly longer event-to-interview time difference in the injured group). However, they do not answer questions related to acute stress reactions or the temporal course of posttraumatic adjustment as it is related to recovery from the physical injury. Second, severity of injury was assessed only at the time of hospitalization but not again at the time of assessment. Thus, our data cannot clarify the degree to which current injury or physical disability status may affect reported PTSD symptoms, nor can it clarify the degree to which pace of physical recovery may be influenced by early PTSD symptoms. Third, the raters completing the SCID and the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale were not blind to the injury status of the participants. While this could result in a potential bias in PTSD diagnosis, this possibility is less likely given that ratings on the self-report measures (i.e., Peritraumatic Dissociation Experience Scale, Beck Depression Inventory, Beck Anxiety Inventory) were remarkably consistent with the raters’ evaluations. Finally, as can be recalled, a sizable proportion (35%) of injured patients refused to participate in the study. This raises the possibility that our sampling procedure was at risk for selection bias. Because of ethical constraints (i.e., lack of consent), we could not collect the necessary data to rule this possibility out. Yet, from the little we do know about these subjects (i.e., the reasons they gave for nonparticipation), it is obvious that such bias, had it existed, could only further strengthen our findings rather than weaken them. Last, and perhaps most important, trauma in this study was defined and assessed only in terms of its objective characteristics (i.e., combat participation). Since it is possible that not all combatants perceive this experience as subjectively traumatic, the current data cannot answer questions related to the unique contribution of physical injury to PTSD only among those whose combat experience was self-identified as traumatic.

In conclusion, our study provides clear evidence that bodily injury during trauma is a major risk factor for subsequent PTSD. Considering that emotional distress is often overlooked among injured patients hospitalized in surgical and trauma units, these findings highlight the importance of paying more attention to psychological aspects of their condition in general and to the early symptoms of PTSD in particular, both during hospitalization and after discharge.