A major focus of schizophrenia research is early detection, particularly during the putative prodromal phase of a psychotic disorder. One recent direction of this research is determining the risk of conversion to full-blown psychosis and developing algorithms of prediction (

1–

3) of this transition. Participants in such studies meet well-established prodromal criteria (

4,

5) and are described as being at ultra high risk or clinical high risk of developing psychosis. In the present study, the term clinical high risk is utilized. Studies typically follow participants for 1 or 2 years. Although reported rates of conversion vary in the literature (

1–

3,

6,

7), a majority of participants consistently do not develop psychosis during the course of a study. The term false positive (

6) has been used to describe such persons. Little, if any, data have been reported about the outcome of these false positive individuals.

The North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study is a consortium of eight research centers that ascertained clinical high-risk individuals and followed them for a period of up to 2½ years (

1,

8). Although originally developed as independent studies, the investigations at the eight sites employed similar ascertainment and diagnostic methods, making it possible to form a standardized protocol for mapping data into a new scheme representing the common components across sites (

1,

8), yielding one of the largest databases of longitudinally followed clinical high-risk cases worldwide. This data set includes 303 prospectively identified treatment-seeking patients who met criteria for a psychosis-risk syndrome based on the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes (

5,

9) and for whom follow-up data were available. Of this sample, 71% had not made the transition to psychosis by the 2.5-year follow-up assessment (

1).

The goal of the present study was to determine the clinical and functional status of those who did not convert to psychosis within the time frame of the study. The aims were to 1) examine the change over time in attenuated positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and functional outcome; 2) determine how many participants still met psychosis-risk syndrome criteria at the follow-up timepoints and how many still had attenuated positive symptoms; and 3) determine whether those who did not convert to full-blown psychosis developed other disorders. It was predicted that there would be an improvement in attenuated symptoms and that there would be less improvement in functioning.

Results

Overall Changes in Symptoms and Functioning

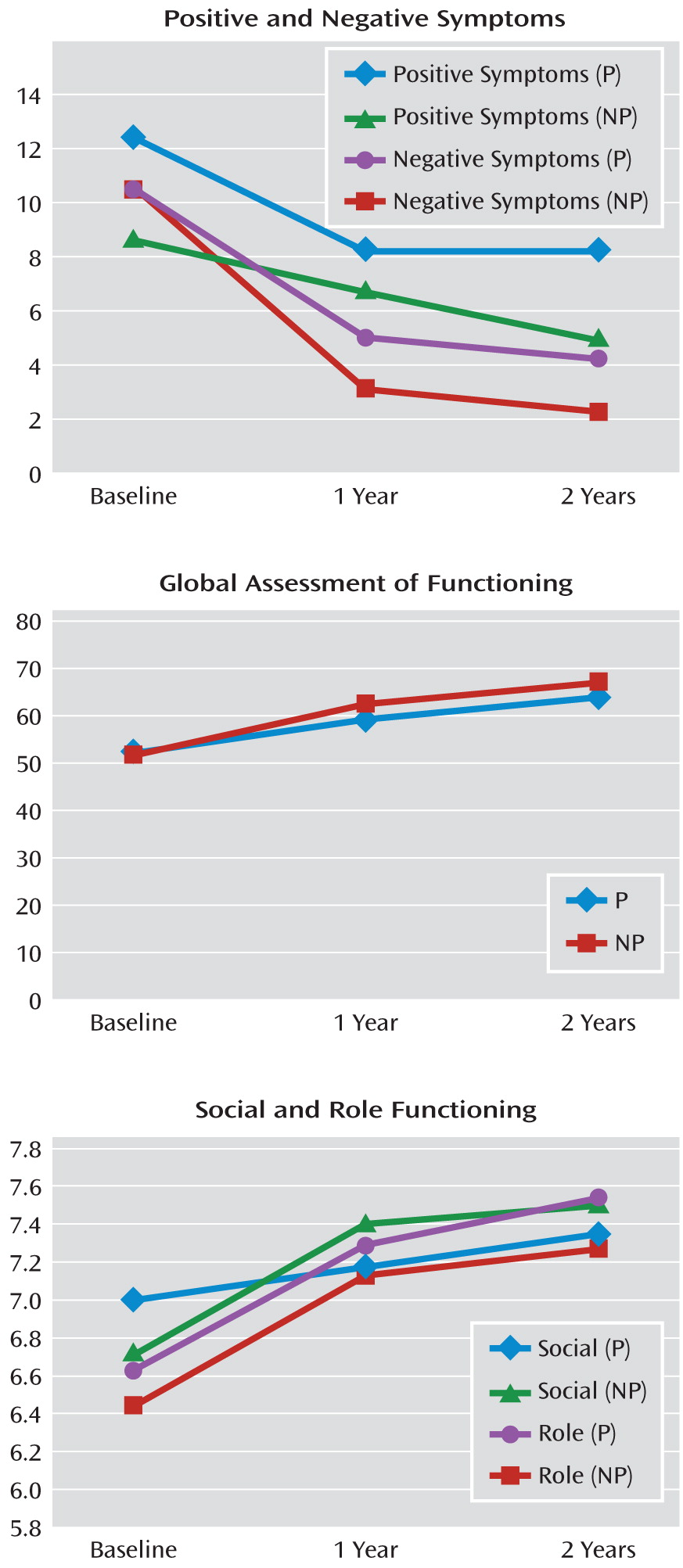

Generalized linear mixed models for repeated-measures data were used to compare the least squares means of positive symptoms, negative symptoms, social functioning, role functioning, and GAF ratings for all participants at baseline, 1 year, and 2 years (

Figure 1). Means and standard deviations for these analyses are presented in

Table 1. Although there was an improvement over time in both positive and negative symptoms, the improvement was only significant between baseline and 1 year (p<0.0001; p<0.001, respectively), not from 1 year to 2 years. Ratings for social and role functioning improved at each assessment period, but the improvement in both social and role functioning was only significant from baseline to 1 year (p=0.002; p<0.0001, respectively). However, there was a significant improvement in GAF scores between baseline and 1 year as well as between 1 year and 2 years (p<0.0001; p=0.04, respectively) (

Table 1).

Using independent t tests, we compared our nonconverting sample with the nonpsychiatric comparison group on social and role functioning. Even though we found improved functioning among the nonconverting clinical high-risk participants at each assessment, this group still performed more poorly on both social and role functioning relative to nonpsychiatric comparison subjects. For social functioning, mean and t values at baseline for the clinical high-risk group versus the comparison group were 6.65 (SD=1.51) versus 8.55 (SD=1.01), t=10.76; at 1 year the values were 7.15 (SD=1.43) versus 8.55 (SD=1.01), t=8.25; and at 2 years the values were 7.30 (SD=1.54) versus 8.55 (SD=1.01), t=6.5 (all values significant at p<0.0001). For role function, mean and t values at baseline for the clinical high-risk group versus the comparison group were 6.67 (SD=1.76) versus 8.71 (SD=1.05), t=10.45 (p<0.0001); at 1 year the values were 7.35 (SD=1.30) versus 8.71 (SD=1.05), t=8.31 (p<0.01); and at 2 years the values were 7.30 (SD=1.46) versus 8.71 (SD=1.05), t=6.36 (p<0.01).

Prodromal Diagnostic Criteria

To meet attenuated positive symptom state, the attenuated positive symptoms must have begun or worsened in the past 12 months. Thus, to meet prodromal criteria at the 1-year follow-up assessment, there had to have been an increase in at least one attenuated positive symptom by 1 point. At baseline, 100% of the present nonconverting sample met criteria for attenuated positive symptom state, only six individuals (5.4%) met criteria at 1 year, and six different individuals (5.4%) met criteria at 2 years. Thus, among the nonconverting sample there was a substantial decline in the number of those meeting actual prodromal criteria at the follow-up assessments.

On the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms, a rating of 0–2 indicates that the symptom does not meet criteria for being attenuated; a rating of 3–5 indicates that the symptom is attenuated with different degrees of severity; and a rating of 6 indicates psychotic intensity. At the 1-year follow-up assessment, 45 (42.9%) participants in the present clinical group had at least one attenuated positive symptom (i.e., one of the five attenuated positive symptoms was rated ≥3), and 31 (40.8%) had at least one attenuated positive symptom at 2 years. Those who still had attenuated positive symptoms at 1 year versus those who did not showed no difference in axis I or II diagnoses or social or role functioning at either baseline or the 1-year follow-up assessment.

DSM Axis I and II Diagnoses

Both axis I and II diagnoses were examined. Axis I diagnoses were grouped into the following clusters: any substance use disorder, anxiety disorder, mood disorder, and mania. The percentages of participants that received these diagnoses at each timepoint are presented in

Table 2. One individual presented with mania at both the 12- and 24-month follow-up timepoints, and another was diagnosed with mania only at the 12-month follow-up assessment. We used Cochran's Q test to determine whether the proportions of participants with or without a given diagnosis were the same at the different assessment times. The results demonstrated that there was a statistically significant difference in having anxiety (p<0.0001) or depression (p<0.0001) overall and in having a substance use disorder overall (p=0.02). Pairwise comparisons using a Bonferroni-corrected level of significance (p=0.017) were performed to compare proportions at each timepoint (

Table 2).

Only 71% of the present nonconverting sample (N=79) were assessed for axis II diagnoses. Of this subsample of 79 individuals, 57% (N=45) had no diagnoses at any time, 29% (N=23) had consistent diagnoses (i.e., the same diagnoses at baseline and follow-up assessment), and 14% (N=11) had emerging diagnoses (i.e., met criteria for axis II diagnoses at a follow-up assessment only). Some individuals had more than one diagnosis. Consistent diagnoses were avoidant (N=5), borderline (N=4), schizotypy (N=3), paranoid (N=3), narcissistic (N=1), and obsessive-compulsive (N=1) personality disorders. Emerging diagnoses were avoidant (N=10), paranoid (N=4), borderline (N=3), and obsessive-compulsive (N=1) personality disorders.

Comparison of Participants Who Did and Did Not Remit

There were no differences in age, gender, or social or role functioning between those whose attenuated psychotic symptoms improved and those whose attenuated psychotic symptoms remained. As would be expected, the one exception was that those who still had attenuated positive symptoms had significantly higher ratings for attenuated positive symptoms at baseline (t=2.6, p<0.01).

Discussion

This is one of the first studies to consider the outcome of individuals at clinical high risk of developing psychosis who do not go on to develop a full-blown psychotic illness over a 2½-year period. A recent, small Swiss study demonstrated evidence of transitory attenuated positive symptoms in some individuals who did not convert (

13). However, it was unclear whether these young participants improved or whether the baseline presentation of the nonconverting group was predictive of another disorder. Overall, in our study, the nonconverting group demonstrated significant improvement in attenuated positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and social and role functioning. Although symptoms declined significantly in this group overall, this was driven by a subgroup whose symptoms improved over time. Furthermore, more than 50% of this nonconverting sample no longer presented with any attenuated positive symptoms. However, despite a statistically significant improvement in functioning, this group remained at a lower level of functioning than nonpsychiatric comparison subjects. This suggests that initial prodromal categorization is associated with persistent disability, at least for 2.5 years.

Axis I diagnoses tended to diminish in number over time rather than emerge, although a relatively high proportion of clinical high-risk participants did have a mood and/or anxiety disorder. Only a small proportion demonstrated an emerging axis II disorder.

Strengths of this data set are its large sample size and the well-defined criteria for a psychosis-risk syndrome (

8). There are also limitations to these data. First, the follow-up evaluation was limited to 1 year and 2 years only. It is likely that a longer follow-up assessment period may have identified additional conversions, particularly since the mean age of this sample at the 1-year follow-up assessment was 19 years and the age of onset of a first episode of psychosis is, on average, 20–24 years (

14). Second, the data were originally collected at independently functioning sites not following a common protocol. Third, the outcome measures are constrained by what was common at all sites (

8). Fourth, it is possible that some individuals had episodes of transient psychotic-like experiences as reported in the general population (

15), but our clinical sample consisted of all help seekers and outcome is mixed in terms of risk status among individuals who do not seek help and are identified in population-based studies as having had psychotic-like experiences (

16). Fifth, other medications (e.g., antidepressants) may have had an effect on attenuated positive symptoms. We did not assess this because details of medication status were not universally collected, and for those who were receiving treatment with other medications, dosage and compliance were unknown. However, a study of the entire North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study sample demonstrated that with the same limitations, antidepressant use was not significantly associated with a decline in attenuated positive symptoms (

17). Finally, we excluded those individuals who were receiving treatment with antipsychotics, and thus we cannot say how they may have been distributed among the three groups (remission, symptomatic, converted).

In summary, we found that help-seeking individuals who met attenuated positive symptom risk criteria appeared to cluster into several groups over a 2.5-year period. Among the 255 participants with 1 year of follow-up data in the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study, approximately 35% developed a psychotic illness, 24% remitted their attenuated symptoms, 20% retained attenuated positive symptoms at lower levels of severity than those present at baseline, and 21% received an antipsychotic drug while in the prodromal phase and therefore could not be used to represent the natural course. Thus, prodromal attenuated positive symptoms may predict a more severe condition in some but by no means all cases. Thus, better prediction requires a range of both clinical and biological marker-predictors in the future

Overall, our results suggest that persons who meet symptom and functional criteria for a psychosis-risk syndrome represent a collection of the following groups: 1) those who are truly at risk for psychosis and are showing the first signs of disorder, 2) those who remit in terms of the symptoms used to index clinical high-risk status, and 3) those who continue to have attenuated positive symptoms. Future work is needed not only to replicate these findings but to extend them over much longer follow-up periods and with more comprehensive assessments that were beyond the scope of this project.