Major depression is common, costly, and most often diagnosed and treated in primary care settings rather than in specialty mental health care settings

(1,

2). In a national probability survey of U.S. adults

(3), 10.3% of more than 8,000 respondents had experienced a depressive episode in the past year and 17.1% had a lifetime history of major depression. Major depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide and exceeds the second-place cause (ischemic heart disease) by a particularly large margin in women

(4). In a recent Institute of Medicine report

(5), more effective care of depression was listed as one of the major unmet health care priorities in the United States.

Effective pharmacologic treatments for depression have been available for more than 40 years. Because of recent improvements in the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of antidepressants

(6), depression is increasingly being diagnosed and treated in the primary care setting. Depression in primary care can be severe, chronic, and recurrent, as well as complicated in its course and presentation

(7–

9). For these reasons, despite government reports

(10), treatment guidelines

(11–

13), consensus statements

(14,

15), and a large body of clinical research

(16), depression remains underrecognized and undertreated

(17–

19). Although the accuracy of diagnosis by primary care physicians may be improving, particularly in patients who are more severely afflicted

(7), undertreatment is less well understood and explored. Important concerns remain about treatment to remission, and there is a need to better understand maintenance treatment in primary care

(17).

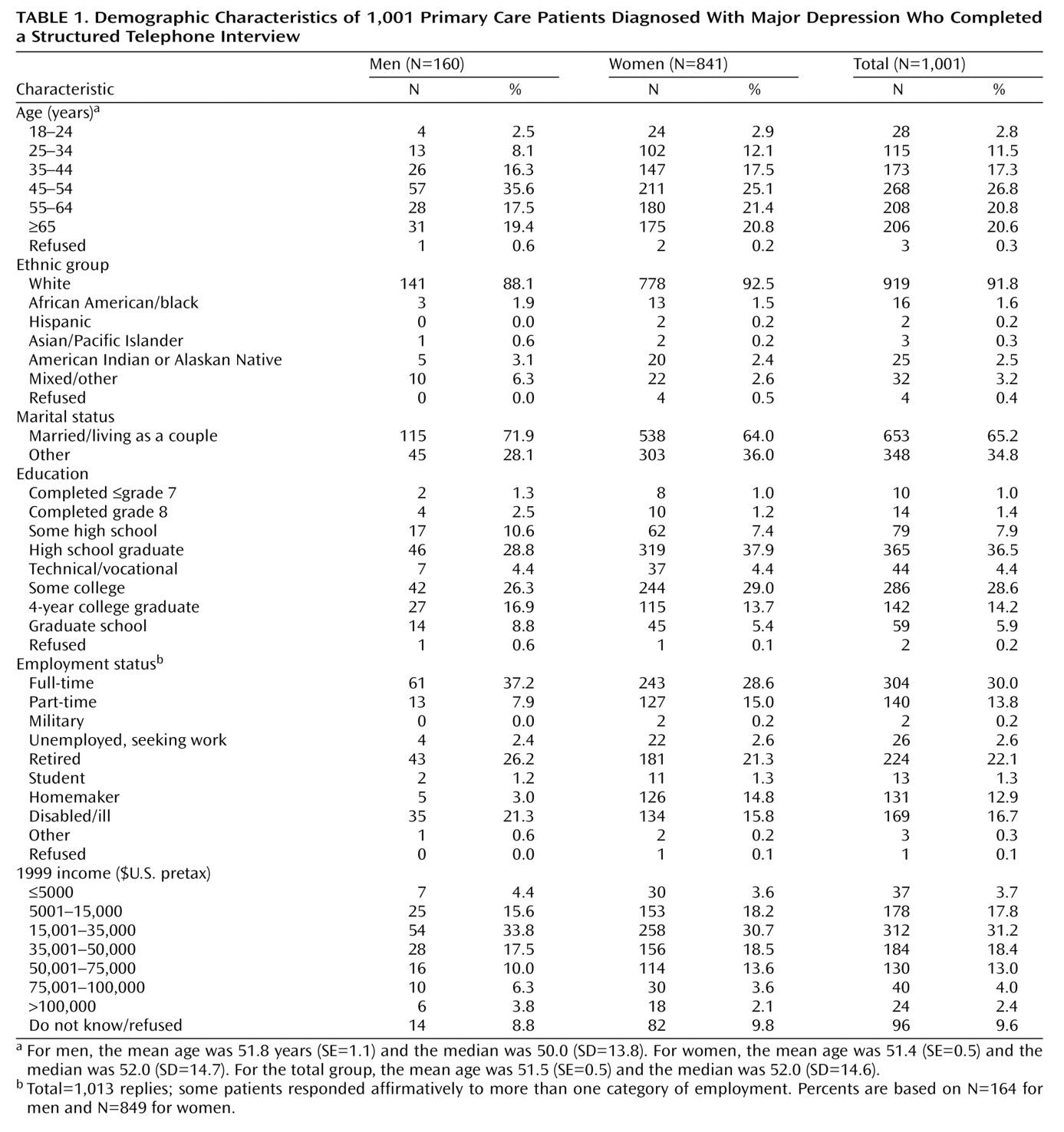

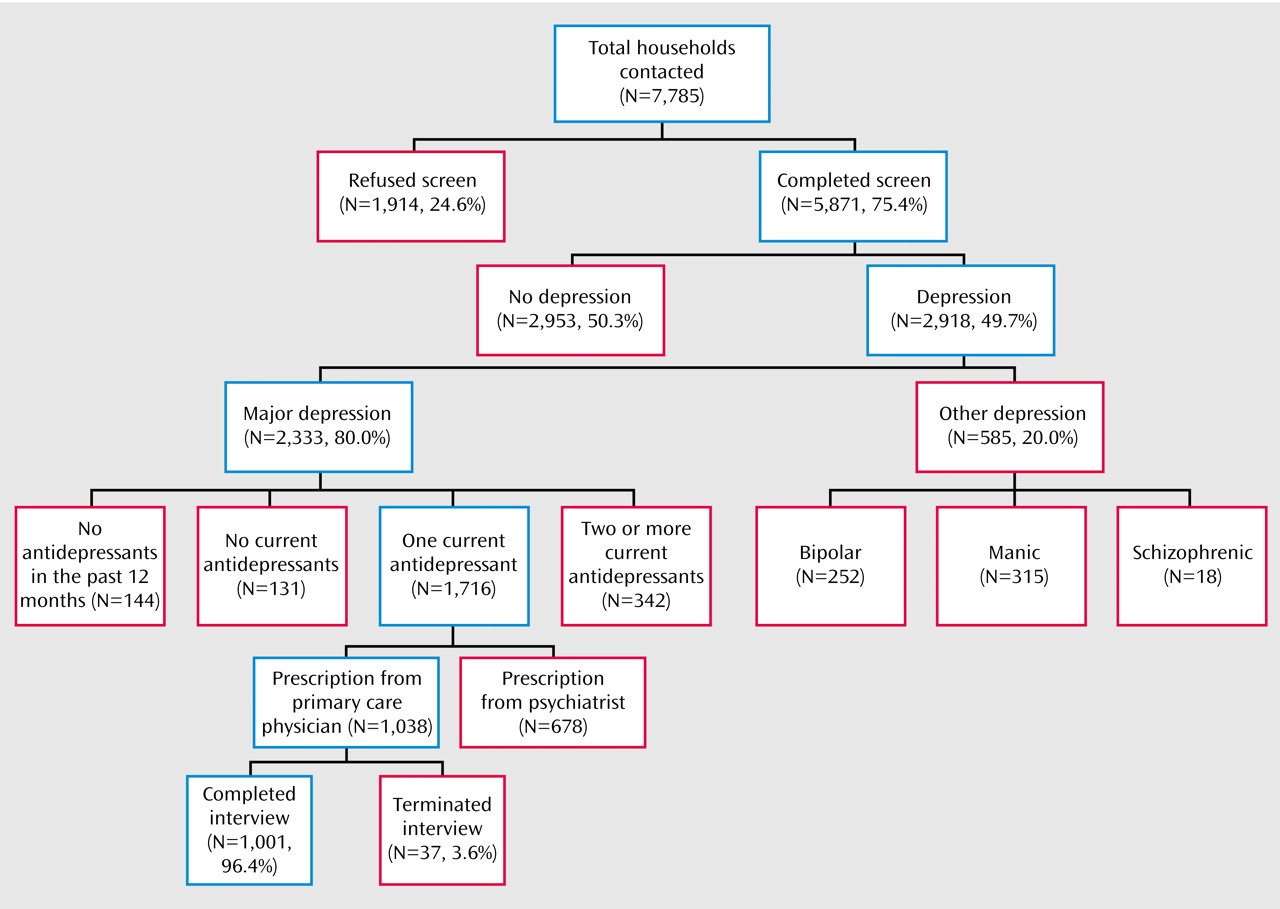

This report describes the findings of a national survey of primary care patients who were selected specifically for chronic and recurrent depression. The study, conducted under the sponsorship of the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance (formerly the National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association), which is the nation’s largest patient-directed, illness-specific organization, was designed to determine the effect of chronic, recurrent depression on patients’ lives and to assess patients’ experience and satisfaction with primary care treatment, particularly the likelihood of being treated to wellness and the barriers to achieving full remission.

Discussion

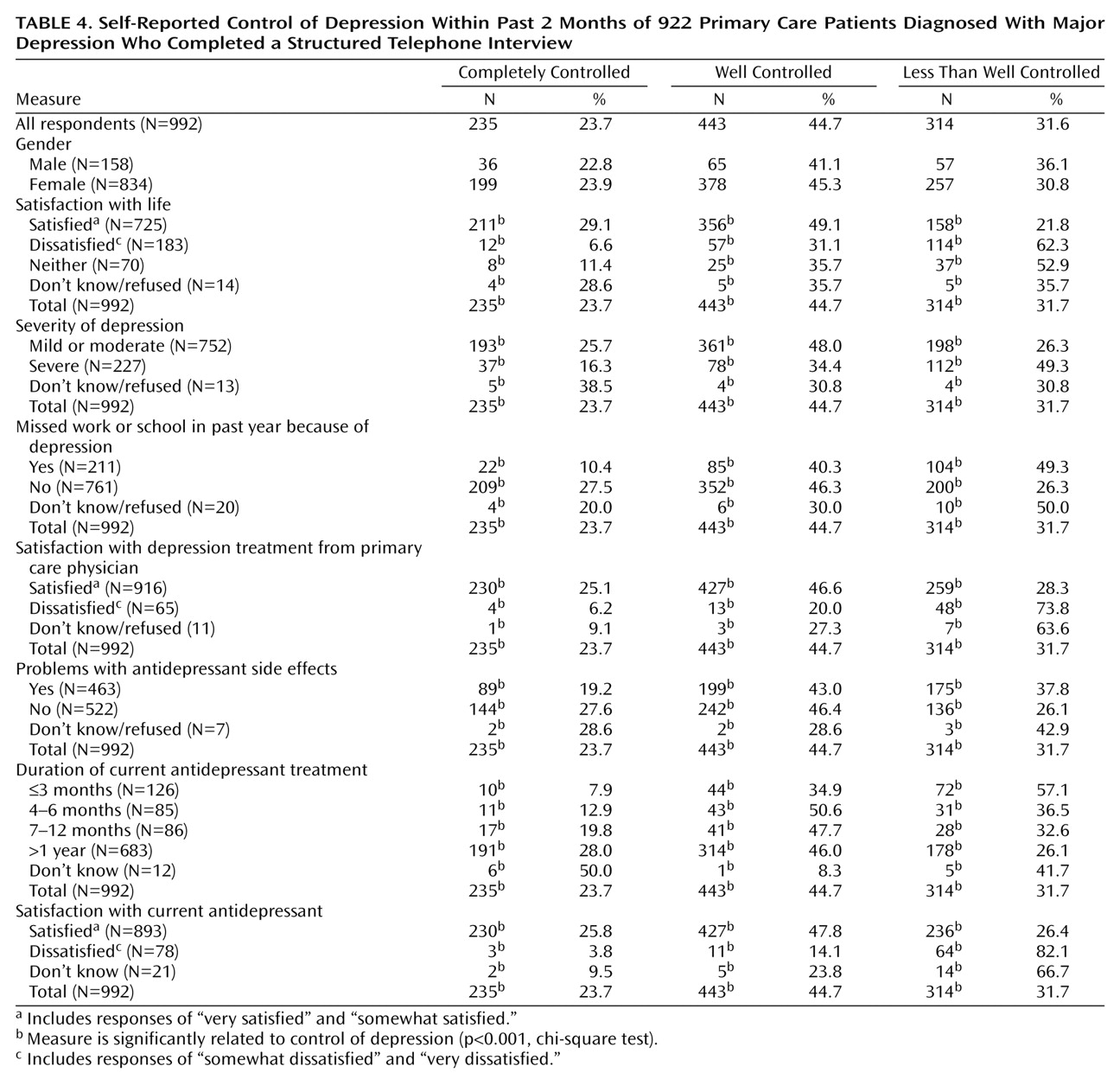

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the experiences of clinically depressed patients with a high level of chronicity and recurrence who were being treated by primary care physicians. Our main findings are that these patients were not being treated to full remission, complete wellness, and full function. Despite this less than optimum clinical outcome, patients had a relatively high level of satisfaction with the care received from their primary care physicians. Patient satisfaction with their physician may be related to the enduring commitment primary care physicians make to their patients’ care, despite a lack of complete response. Moreover, patients may perceive that the barriers to full recovery are not physician specific, and they may be more accepting of incomplete resolution of depression than for other illnesses. What is unclear and bears further study is which specific barriers are amenable to improvement, whether the proportion of nonremitting patients is larger than the proportion in other chronic illnesses, and the degree to which these barriers are physician centered, patient centered, or system centered.

There are many known physician- and patient-specific barriers to depressed patients’ achieving full symptom resolution

(14,

16,

20–23). Patients may experience incomplete response because of inadequate treatment strategies, poor adherence to the prescribed regimen, or inadequate patient education about the therapeutic plan, particularly the need for monitoring therapeutic response and adjusting the medication regimen. All of these barriers are likely interrelated and may stem from inadequate communication between the primary care physician and the depressed patient.

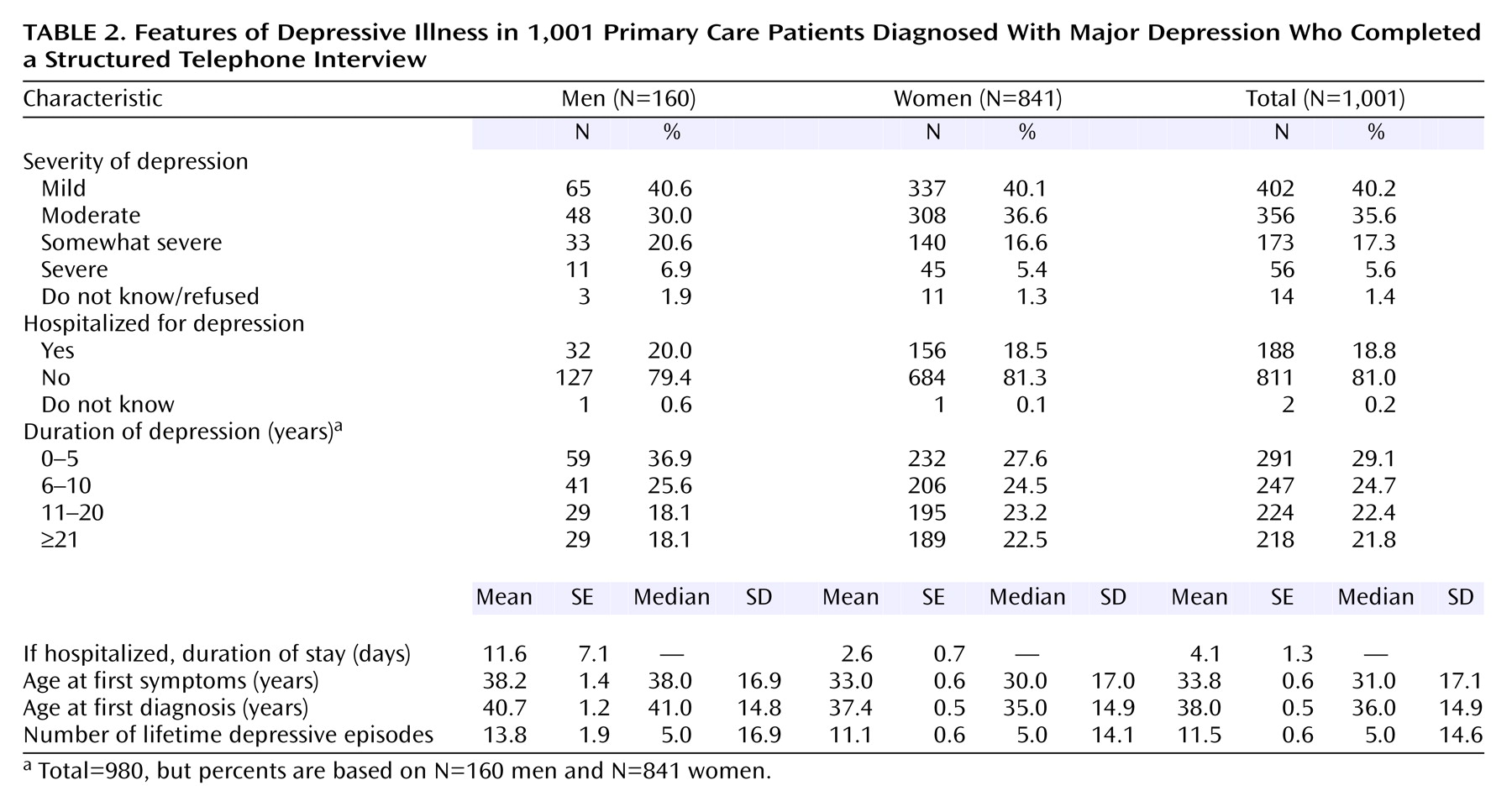

The patients in this study had a high level of education, were primarily Caucasian, had ready access to medical care, and were in active treatment with a primary care physician at the time the survey was conducted. Despite these advantages, which are not enjoyed by more general patient populations, there was a mean gap of more than 4 years between the age at which the patients reported first experiencing depressive symptoms and the age at which they received a diagnosis. We could not determine whether patients did not seek medical attention when they became symptomatic or did seek treatment but were not diagnosed properly. It is not uncommon for depressed patients to seek general medical care frequently and persistently; usually they receive extensive medical evaluations and testing without definitive results or an accurate depression diagnosis

(24–

26).

The mean age at which antidepressants were prescribed was 39.8 years, nearly 2 years after diagnosis, suggesting a possible focus on psychotherapy or watchful waiting after the initial diagnosis was made, although our study was not designed to assess referral for psychotherapy. On average, a 6-year gap existed between the time of symptom onset and the time that antidepressant medication was initiated in this group of patients. We could not determine whether medication was indicated during that interval or how care was provided during that time. It is clear, however, that considerable time elapsed from the time of symptom onset to the initiation of medication, with an increasing level of morbidity, dysfunction, and the possibility of greater risk of chronicity and recurrence. We do not know if there were clues that would have helped the physician shorten this delay, but this topic is worthy of future exploration.

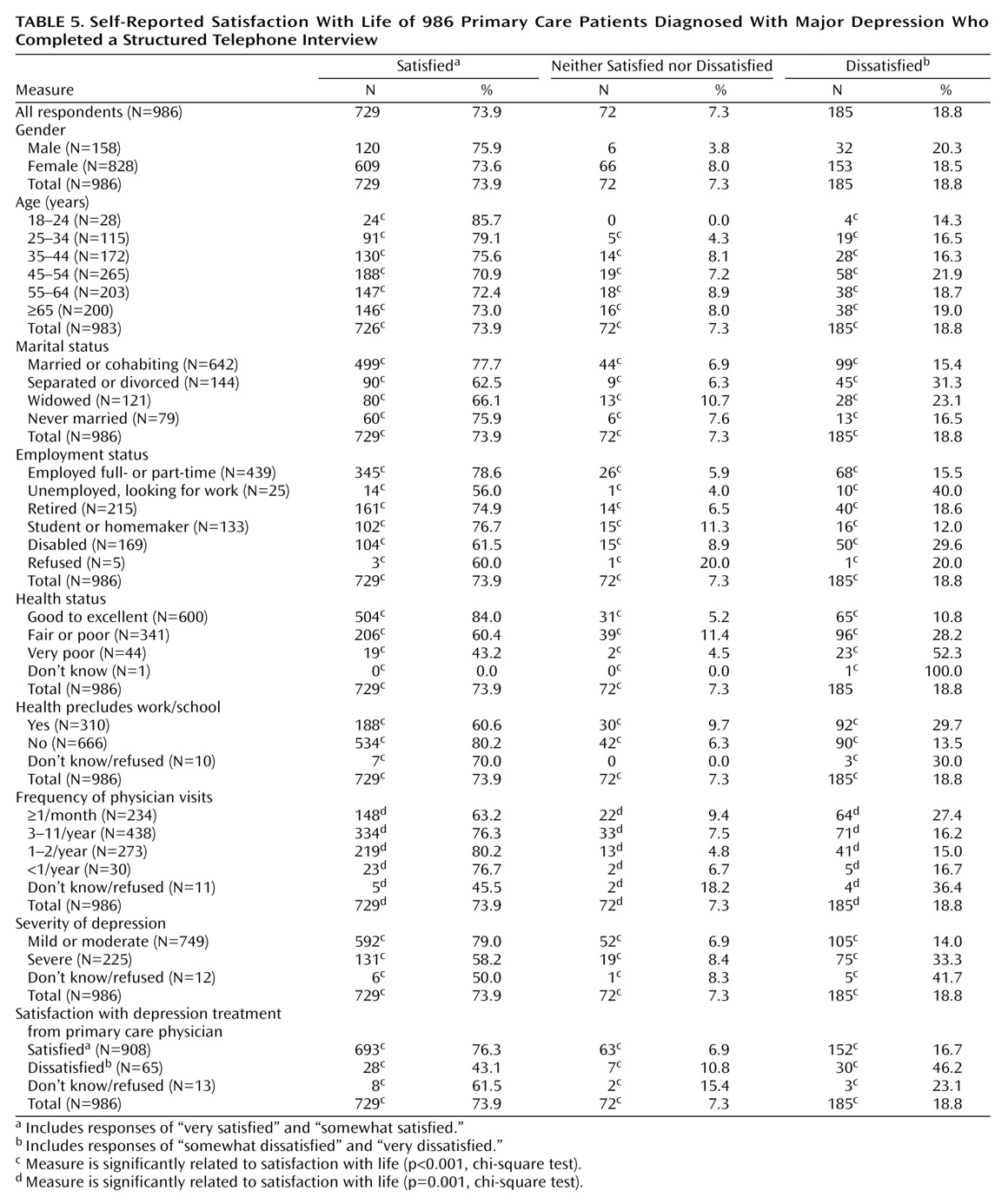

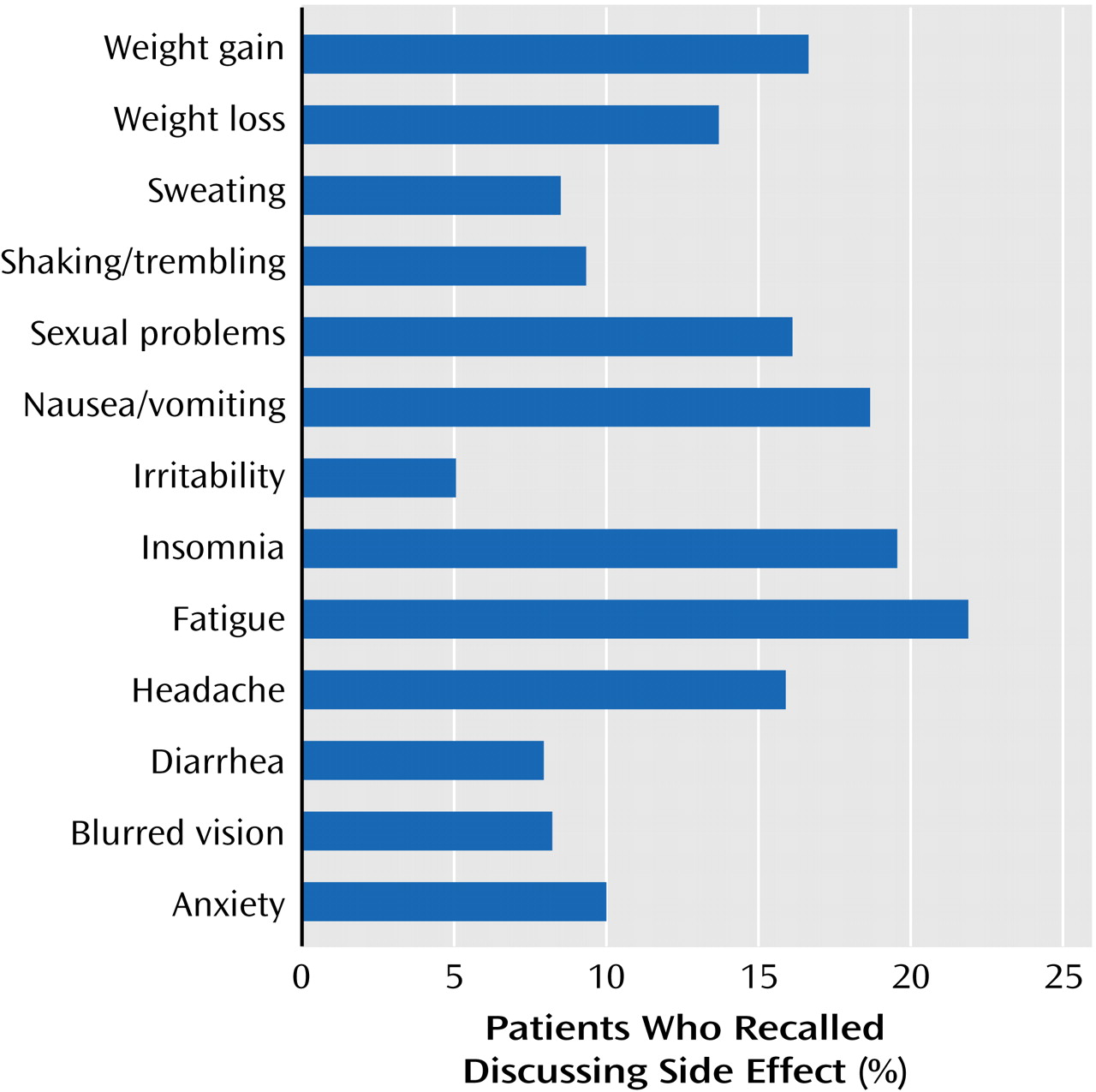

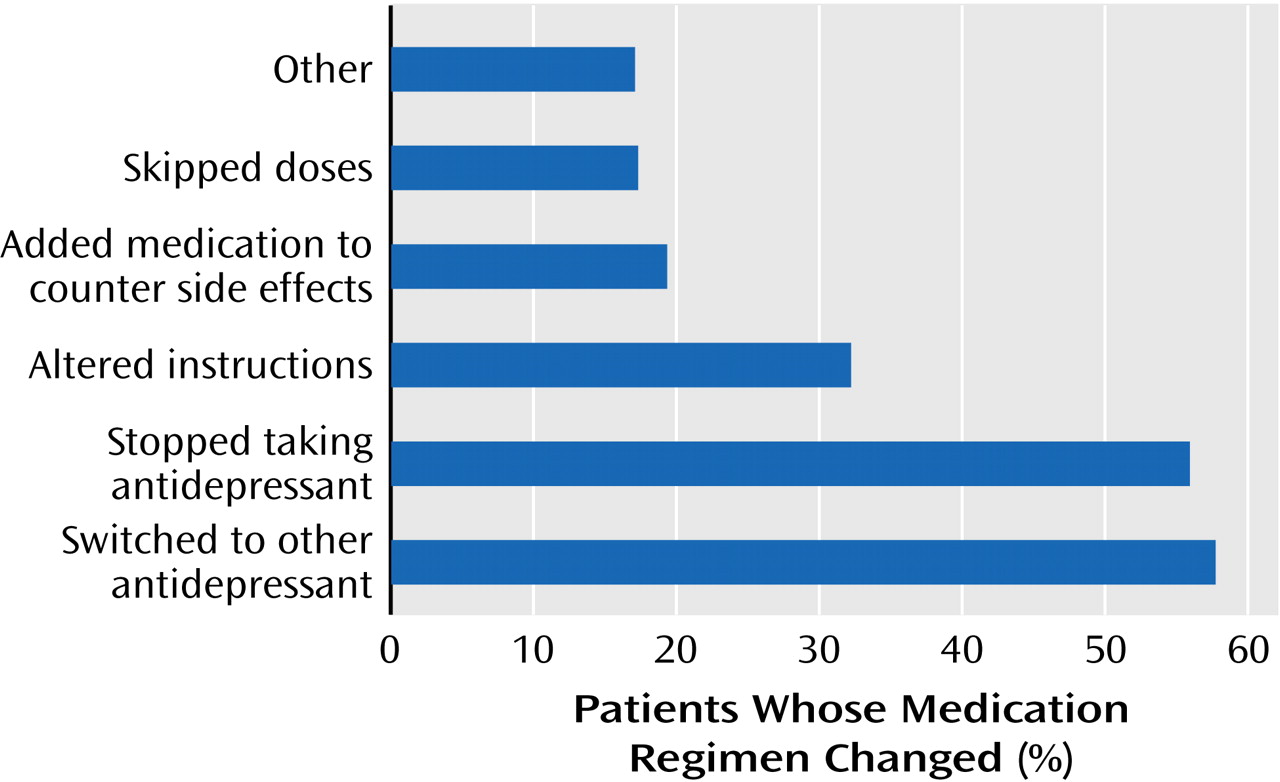

Approximately half of the patients reported having difficulties with antidepressant side effects. One out of four patients was not adherent to the prescribed antidepressant regimen. The cost of antidepressant treatment, lack of insurance coverage, side effects, or resolution of depressive symptoms were the most commonly cited reasons that patients elected to stop taking their medication.

Several aspects of physician-patient communication may be amenable to improvement. Many patients desire more active communication about side effects, a patient-centered and collaborative style of communication and treatment planning, and a shared commitment to achieving wellness and full symptom resolution. A team-building approach, which includes strong patient-physician relationships and shared decision making, has been shown to increase adherence and treatment outcomes

(5,

27–30). Likewise, patients who received specific educational messages about how to take their medication (e.g., “The medication is intended to be taken for several months before we discuss stopping it,” “Do not stop just because you feel better,” “Take it for at least 4 weeks before assessing side effects”) and information about how to obtain answers to their questions are more likely to adhere to the treatment plan

(31).

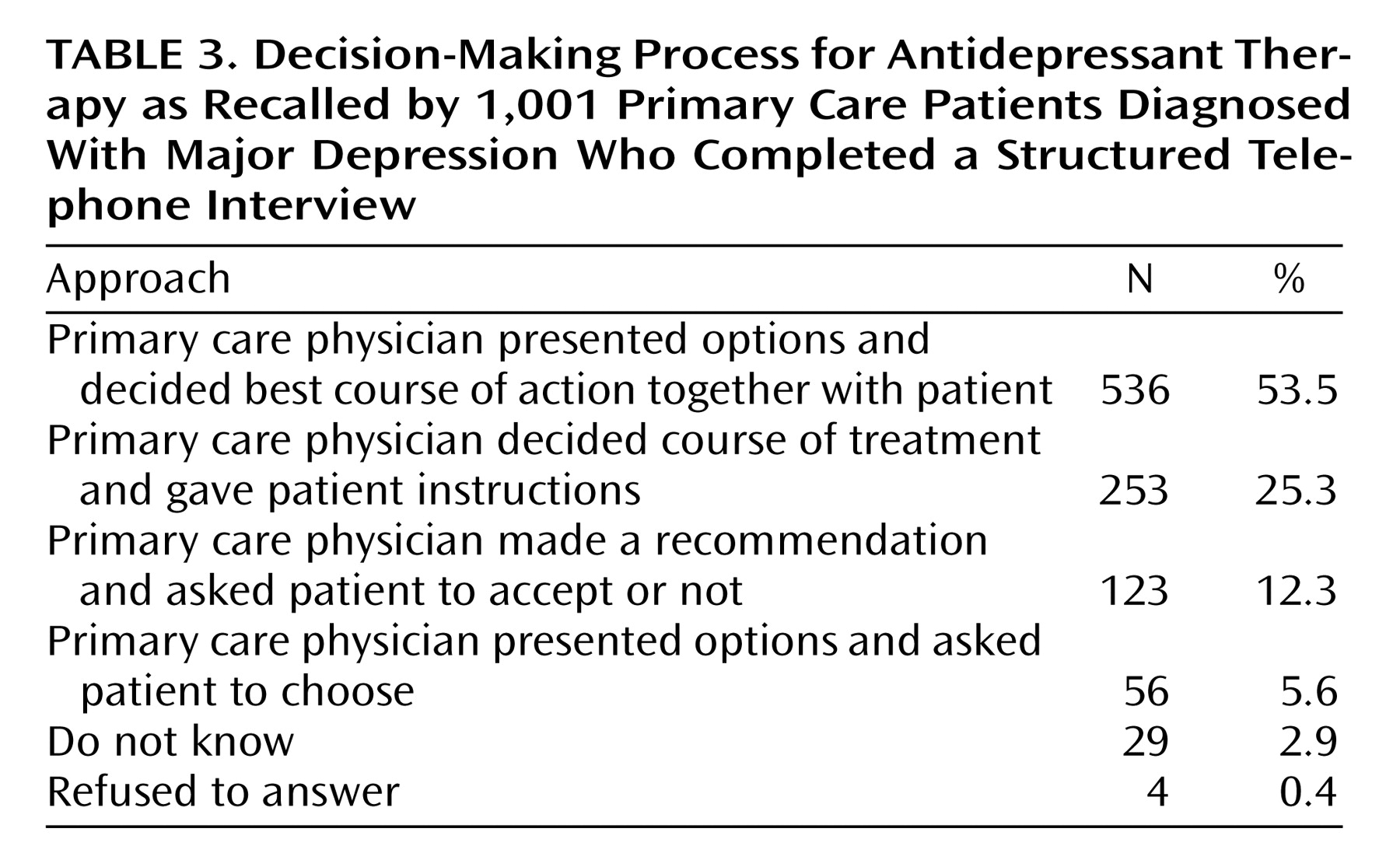

According to our findings, an important area in which communication could be improved is the way in which treatment decisions are made. Nearly 60% of the patients thought that treatment decisions were made jointly, and indeed this approach was preferred by nearly three-quarters of the patients. More than one-third of the group reported that a treatment course was selected for them and instructions provided. Patients who disagree with the choice of antidepressant that is prescribed by their primary care physician or who experience significant or unanticipated side effects are less compliant with their medication regimen

(31) and thus may not experience full symptom resolution. In this study, more than one-third of respondents said that side effects made them switch to a different antidepressant, and one-sixth said that side effects made them change the way they took their medicine. Our findings agree with several reports in which nearly half of depressed patients stopped or changed the way they took their antidepressant medication because of side effects

(31–

35).

The usual limitations of retrospective and self-report telephone surveys restrict the generalizability of our findings to other groups of primary care patients. The sample included few minority respondents, which is not uncommon in national telephone surveys

(36). The sample, by design, included only those patients who had been depressed and used antidepressants for at least 18 months, thus introducing selection bias by excluding patients who had discontinued treatment and who may have been dissatisfied with elements of their treatment. Consistent with the findings from a large, national epidemiologic study, our sample of patients with depression was predominantly female, and their first depressive episode occurred in the third decade of life

(3,

37).

Recall bias is a significant source of error in interpreting the results, particularly with regard to age at onset, side effects, treatment plans, and options that were discussed with physicians. A prospective, randomized, double-blind assessment of treatment experiences (including psychotherapeutic interventions), correlated with physician perceptions and structured observation, would be a valuable next study, as would the assessment of outcomes and responses associated with different communication styles. The findings of a further research study that included a matched comparison group of patients who had achieved full remission would be of particular interest.

Since the diagnosis and treatment of major depressive disorder continue to emphasize the central role of the primary care physician, educational programs, patient advocacy, health care system changes and resources, and quality of care measures should focus on physician-patient communication, incomplete resolution, and process of care problems highlighted by these data. We have demonstrated in this large national telephone survey of predominantly married, female patients that even in a seemingly optimal clinical setting with educational and social support resources, many patients with chronic, recurrent depression are inappropriately accepting of treatment planning in which they are not engaged as full partners, treatment regimens that do not lead to full symptom remission, and an incomplete discussion of potential side effects. As is the case with other chronic illnesses, these deficiencies should not be accepted in the care of patients with chronic depression, even when patients appear to be satisfied with the care they receive.