Changing medications is a common feature of psychiatric practice, and medication changes often are part of life for people with schizophrenia. Rates of switching medication vary by setting and by provider within setting, suggesting that the decision to “stay or switch” is influenced by providers’ prescribing practices as well as by patient factors

(1,

2) . Few randomized trials speak to this stay-versus-switch question, so it is fortunate that data from phase 1 of the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study

(3) afford a rare opportunity to examine experimentally the effectiveness of staying with a given antipsychotic versus switching to another one

(4) .

In the phase 1 results from CATIE, 23% of the participants randomly assigned to olanzapine already were on a regimen of olanzapine monotherapy at the time of study entry, 18% of participants randomly assigned to risperidone were already receiving risperidone monotherapy, and 5% of participants assigned to quetiapine were already receiving quetiapine monotherapy

(3) . The phase 1 report also noted that individuals who were receiving olanzapine or risperidone treatment at the time of study enrollment had longer times-to-all-cause-discontinuation than did those who entered the trial receiving different or no antipsychotic medications. The purpose of this report is to compare all-cause treatment discontinuation for patients whose random assignment resulted in staying with the same antipsychotic they were already receiving at baseline versus switching to a different one, and to examine the extent to which excluding patients randomly assigned to continue taking their baseline medication would affect the discontinuation rates observed in the CATIE trial.

Method

Study Participants

As previously reported, individuals were eligible for participation in the CATIE study if they were ages 18 to 65, had received a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and were judged appropriate for treatment with oral antipsychotic medications (see Stroup and colleagues

[5] for more detailed inclusion criteria and Lieberman and colleagues

[3] for more detailed information about study methods; additional information is also available in the supplement that accompanies the online version of this article). We examined subsets of the 1,432 study participants used in the CATIE phase 1 analyses.

Question 1: Stay Versus Switch?

The first group of analyses addressed the question, “Did individuals who were randomly assigned to stay with the same antipsychotic medication they were already taking at study entry discontinue their assigned treatment at a different rate than individuals assigned to switch?”

We addressed this question in two ways:

1. Staying with versus switching to treatment: For those participants randomly assigned to treatment with olanzapine or risperidone, what was the impact of having been randomly assigned to stay with the same medication versus switching to these treatments from a different antipsychotic?

2. Staying with versus switching from treatment: For those participants who entered the study already receiving olanzapine, risperidone, or quetiapine monotherapy, what was the impact of being randomly assigned to stay with the same medication versus switching from the medication to one of the other four antipsychotics?

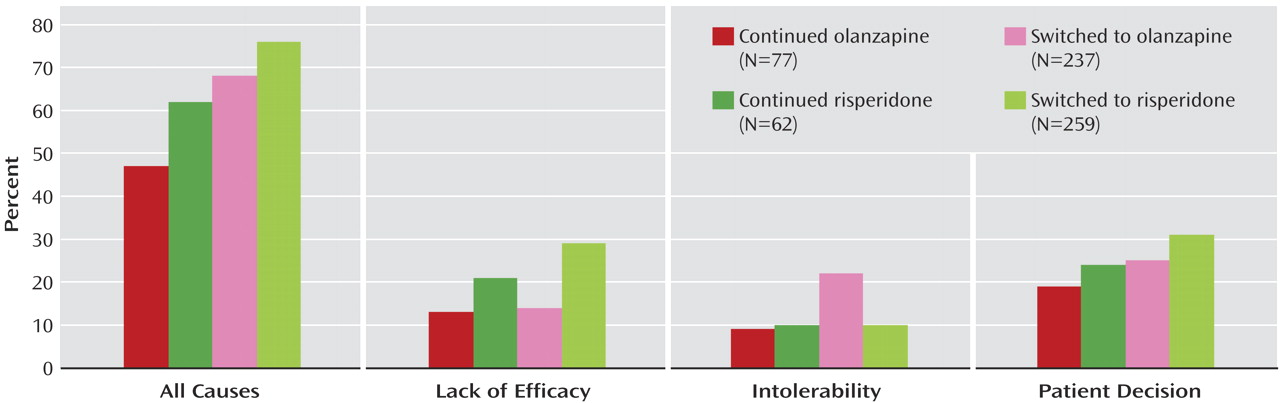

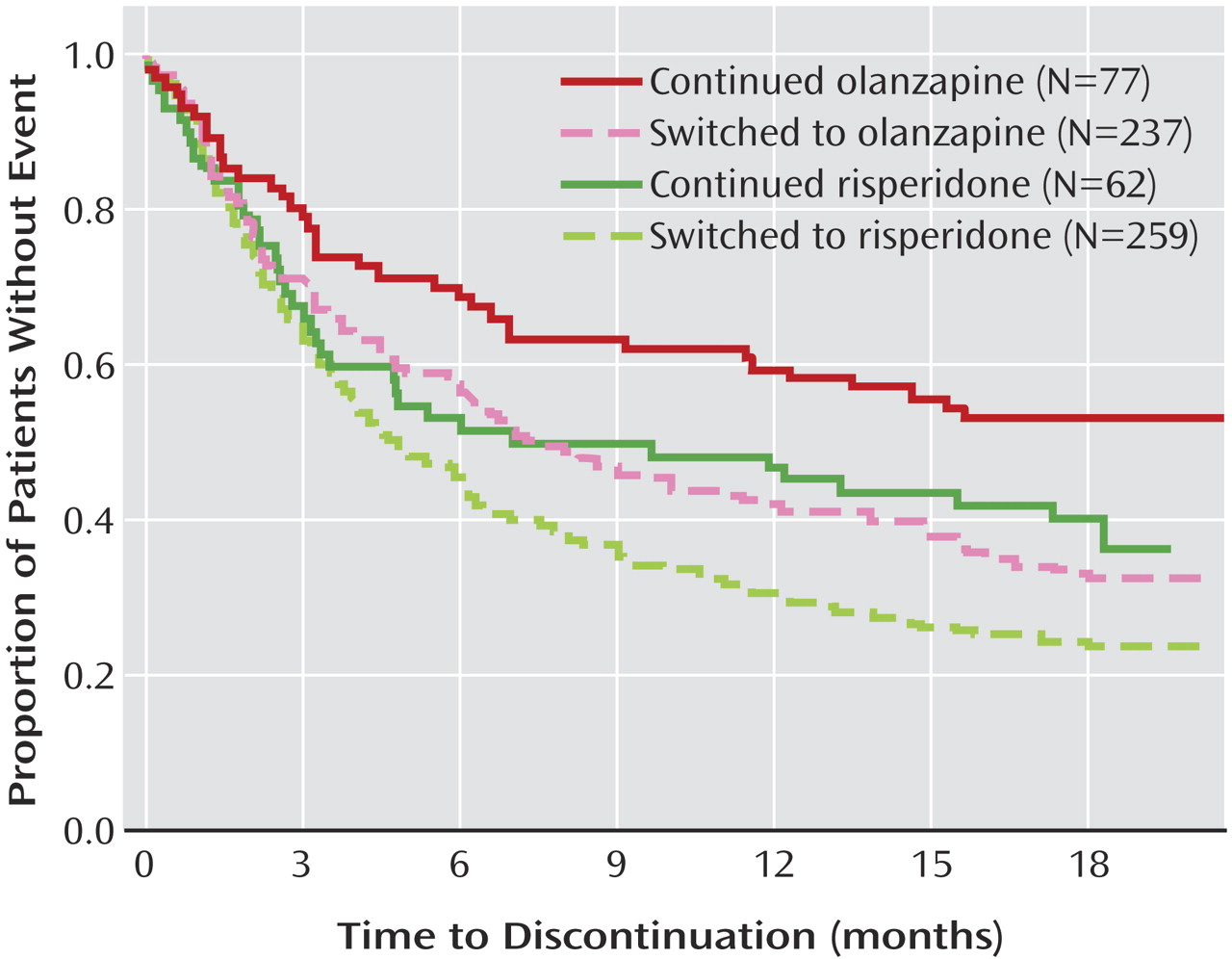

The subset of study participants for the “staying with versus switching to” analysis consisted of those participants in the CATIE phase 1 intent-to-treat analyses who were assigned to take either olanzapine or risperidone, since these groups included enough study participants to allow statistical comparisons (only 5% or fewer of study participants assigned to take quetiapine, perphenazine, or ziprasidone were already taking these medications as monotherapy at baseline). We grouped these individuals into two groups: “stayers” versus “switchers.” “Stayers” were individuals assigned to the same medication they were receiving at study entry (with what ever dosage retitration was permissible within the study protocol of 1, 2, 3, or 4 blinded capsules). “Switchers” were individuals assigned to either a different medication or who were not receiving an antipsychotic at study entry (additional information on the stayers and switchers are included in the supplement that accompanies the online version of this article). Within the olanzapine double-blind treatment group, 77 (25%) of 314 participants were stayers and the remaining 237 (75%) were switchers. Within the risperidone double-blind treatment group, 62 (19%) of 321 participants were stayers and the remaining 259 (81%) were switchers. We examined time to all-cause discontinuation and time to discontinuation due to inefficacy, intolerability, and patient decision.

The subset of study participants for the “staying with versus switching from” analysis consisted of the 319 individuals receiving olanzapine monotherapy, the 271 individuals receiving risperidone monotherapy, and the 94 individuals receiving quetiapine monotherapy at study entry who were included in the intent-to-treat analysis of the original findings

(3) . We examined time to all-cause discontinuation for this subset of individuals. Using those receiving olanzapine monotherapy at baseline as an example, we compared those assigned to stay with olanzapine versus those assigned to switch from olanzapine to risperidone, quetiapine, ziprasidone, or perphenazine.

Question 2: Same Results If Stayers Omitted?

If individuals whose random assignment resulted in staying with the antipsychotic medication they were taking at study entry were excluded, would the CATIE phase 1 results be different?

For these analyses, we excluded those individuals who were randomly assigned to continue taking an antipsychotic medication they were receiving at baseline either as monotherapy or with another antipsychotic. Specifically, we excluded 209 (15%) study participants: 93 assigned to olanzapine (28% of the group), 74 assigned to risperidone (22% of the group), 31 assigned to quetiapine (9% of the group), four assigned to perphenazine (2% of the group), and seven assigned to ziprasidone (4% of the group).

Statistical Analyses

All of the statistical tests were 2-tailed. For evaluation of the “staying with versus switching to” question, we paralleled the original analysis strategies for the phase 1 CATIE findings

(3) using Kaplan-Meier survival curves to estimate the time to discontinuation of treatment and Cox proportional-hazards regression models

(6) to compare differences in discontinuation rates for the double-blind treatments (olanzapine versus risperidone) and the prior medication groups (switched from study entry medication versus stayed with study entry medication). The Cox model was stratified according to site and adjusted for tardive dyskinesia status and whether the individual had had an exacerbation of schizophrenia in the preceding 3 months. Additional Cox models included a test of the interaction between double-blind medication assignment (risperidone, olanzapine) and group (stayer, switcher), as well as the effect of potential baseline covariates and the moderating effect (interaction) of covariates on staying versus switching. Also paralleling the original analyses for the phase 1 findings

(3), we examined the effect of staying versus switching on changes in total score on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) through time, applying a mixed model that included the same fixed covariates as for the time to discontinuation and added baseline PANSS score, time (classified into months), and interactions between double-blind treatment and time, baseline PANSS score and time, stay versus switch status and treatment, and baseline PANSS score and stay versus switch status. An additional model tested for a 3-way interaction between double-blind treatment, stay versus switch status, and time.

For evaluation of the “staying with versus switching from” question, we used Kaplan-Meier survival curves for each subset of individuals based on monotherapy medication at study entry to estimate the time-to-discontinuation of treatment for each of the five double-blind medications. If the curves appeared to be substantially different across the double-blind treatments, we applied a post hoc Cox proportional-hazards regression model

(6), with adjustment for whether the individual had had an exacerbation of schizophrenia in the preceding 3 months and whether the person had tardive dyskinesia at study entry, to quantify the strength of double-blind treatment group differences in discontinuation rates. We also applied ANOVA and chi-square analyses to examine differences in background characteristics among baseline medication groups (olanzapine monotherapy; risperidone monotherapy; quetiapine monotherapy; no medication; more than one antipsychotic including olanzapine, risperidone, or quetiapine; and monotherapy or polypharmacy with agents other than olanzapine, risperidone, or quetiapine).

To reproduce the primary CATIE results excluding the “stayers,” we used the same methods as in the main paper

(3) first to compare olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, and perphenazine for all individuals without tardive dyskinesia at baseline, and if an overall difference was found, subsequently compare perphenazine versus each of the three atypical antipsychotics using a Hochberg adjustment for multiple comparisons

(7) and compare olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone for all individuals. Secondary comparisons involving ziprasidone, which was added to the study after 40% of patients had enrolled, were limited to the cohort of patients enrolled after ziprasidone was added, and also received a Hochberg adjustment. Comparisons of ziprasidone with perphenazine excluded tardive dyskinesia patients. We used Kaplan-Meier survival curves to estimate the time to discontinuation of treatment. We used Cox proportional-hazards regression models

(6), stratified according to site with adjustment for whether the individual had had an exacerbation of schizophrenia in the preceding 3 months and tardive dyskinesia status where applicable, to test the significance of double-blind treatment group differences in discontinuation rates.

To evaluate how the exclusion of individuals who had been randomly assigned to stay with their baseline medication affected power or enhanced or diminished the primary findings as originally reported

(3), we compared the power of the two sets of analyses (original analyses versus this subset) and, for each pairwise comparison of double-blind treatments, we computed the ratio of the original hazard ratio to the hazard ratio produced in the analysis of this subset.

Discussion

In clinical practice, people with schizophrenia sometimes change medication in hope that the next medication will work better than the current one. The analyses of the CATIE phase 1 findings presented here suggest that the likelihood of finding a medication that fits better than the current medication (as measured by time to all-cause discontinuation) is a function both of the medication being switched from and the medication being switched to, and that such switches have only modest success rates among the medications used in CATIE phase 1. The subgroup analysis of CATIE patients entering the study on a regimen of olanzapine monotherapy indicated that, on average, it may be better to stay with olanzapine than to switch to one of the other antipsychotics used in phase 1. Similarly, analyses of patients receiving double-blind olanzapine and risperidone treatment indicated that stayers, on average, fared somewhat better than patients newly switched to these two medications (about half of stayers versus over 70% of switchers discontinued their assigned medication).

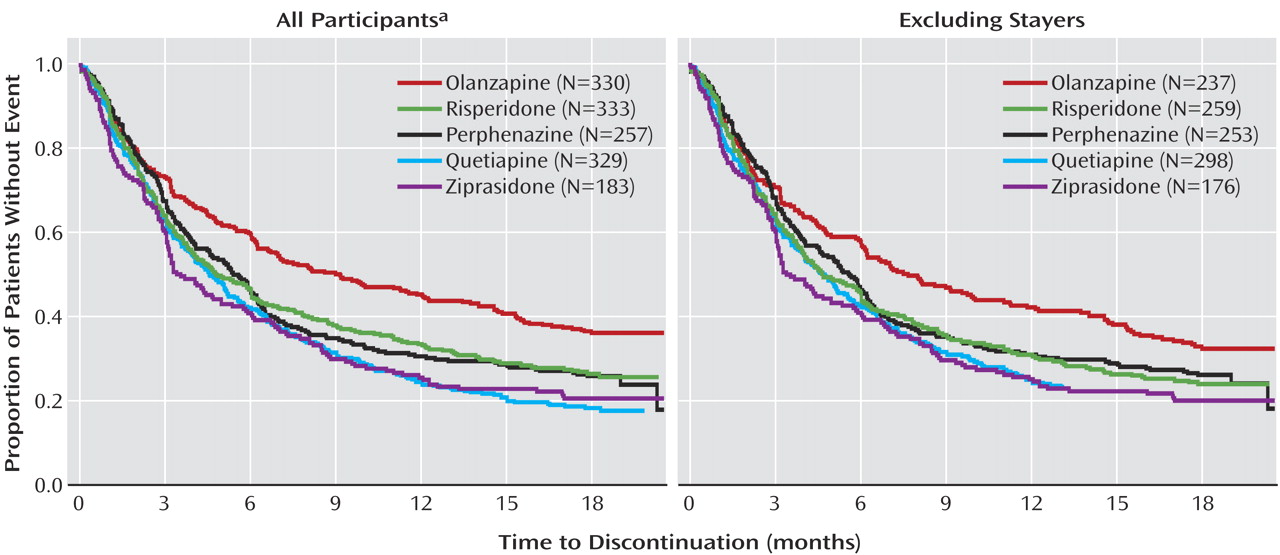

When individuals who did not switch medications at study entry were excluded from the analyses, the core findings of CATIE were supported (

Figure 3 ), although statistical significance was attenuated both because of loss of power with the reduced sample size and because removing stayers removed a number of individuals receiving olanzapine who tolerated that medication relatively well. As shown in

Figure 3, the separation between the olanzapine curve and the other curves is still apparent when stayers are excluded, but the separation is narrower than when all participants are included. Under the CATIE study conditions where side effects were monitored, individuals newly treated with olanzapine (olanzapine switchers) were more likely to discontinue their assigned medication due to intolerability than were individuals assigned to olanzapine who were already receiving it at study entry (olanzapine stayers). Olanzapine switchers also were more likely to discontinue their assigned medication due to intolerability than were individuals receiving risperidone at study entry who were assigned to risperidone (risperidone stayers) and individuals who were newly treated with risperidone (risperidone switchers) (data in online supplement). These limitations in olanzapine’s tolerability acted to offset some of its superior efficacy as originally reported

(3) .

The finding that risperidone or olanzapine stayers fared better than switchers raises the more general question of the extent to which switching from any nonclozapine oral antipsychotic monotherapy to another is a hopeful treatment strategy. These findings suggest that, unless the clinical situation requires a medication change, prescribers should take steps to optimize current medication regimens (e.g., via dosage changes, behavioral or psychosocial interventions, adjunctive medications) before switching medications. Certainly, individuals’ desires to try a different medication should be respected. What we are stressing is the clinical appropriateness of working diligently with patients to maximize the effectiveness of the current antipsychotic before taking on the risks associated with a medication change in hopes that the next one will be more satisfactory (i.e., taken for a longer period of time). Short of a compelling clinical indication to switch medication, different individuals (whether patient or prescriber) have different thresholds for being willing to continue a medication given limitations in effectiveness or side effects. For example, one individual might be willing to accept an increase in a particular side effect in exchange for symptom improvement, while another individual may choose to change to a medication with less symptom control in order to ameliorate particular side effects. On the one hand, changing medications offers the possibility of further symptom improvement or reduction of side effects experienced with the current antipsychotic medication. On the other hand, changing medications risks destabilizing a formerly stable person

(8) as well as increases the burden on already stretched clinical resources from both increased monitoring following a medication change and increased clinical attention if symptom exacerbations occur. The field has very few randomized trial studies examining the relative effectiveness of staying with one’s current antipsychotic treatment versus switching to another

(8,

9), hence this opportunity to examine the phase 1 CATIE data from this perspective is particularly timely.

In cases where medication changes are clinically warranted or where individuals prefer to try something new, the analyses of CATIE phase 1 presented here along with the results of CATIE phase 2 may help inform medication choice. Specifically, in phase 2 of CATIE, some of the people who discontinued their phase 1 medication stayed with their new phase 2 medication for the remainder of the study, indicating a successful antipsychotic medication switch. When clozapine was a treatment arm, such successful switches were significantly more likely, when considering discontinuation for any reason, among individuals who switched to clozapine relative to quetiapine and risperidone but not to olanzapine

(10) . In addition, individuals receiving clozapine were significantly less likely to discontinue treatment for reasons of inefficacy than were individuals receiving any of the other atypicals (10). When clozapine was

not a treatment arm and when considering those who discontinued the previous medication for reasons of inefficacy, olanzapine was superior to quetiapine and ziprasidone, and risperidone was superior to quetiapine

(11) .

This study has several limitations worth noting. First, the post hoc analyses were exploratory and, as such, carry concerns about spurious findings from multiple comparisons. Thus, the results should be interpreted as preliminary, and future randomized clinical trials should address the stay versus switch question directly. Second, sample sizes were only sufficient to evaluate with confidence the relative effectiveness of staying versus switching for two antipsychotic medications, olanzapine and risperidone. We recognize that other antipsychotic medications may behave differently under these stay or switch conditions. Indeed, randomized trial evidence indicates that individuals with treatment-resistant schizophrenia are better off switching to clozapine than staying with conventional antipsychotics, at least with respect to lowered likelihood of rehospitalizations

(9) . Hence, future studies should examine this question for other agents and for larger numbers of stayers. Because so many individuals with chronic disorders gain some benefit from their current medication (so-called “partial responders”), the “stay versus switch” question has great day-to-day clinical significance and is not addressed by designs where individuals switching to one medication are compared with individuals switching to another medication. Third, dosages of the medications in the double-blind condition may have advantaged some medications (e.g., olanzapine) and not others (e.g., quetiapine and ziprasidone). Finally, we note that these results apply to individuals who were enrolled in the CATIE phase 1 trial, and these individuals varied widely in clinical severity. Because random assignment to the medication taken at baseline was possible for participants taking one of the study drugs, staying on this medication had to be considered a viable clinical option. Those who were completely satisfied with their medication would not have been expected to enter the study; thus, CATIE participants who were taking one of the study drugs at baseline were incompletely satisfied with this drug but did not absolutely require a change.

The results of these analyses are consistent with a critical finding in all previous reports from CATIE: the available antipsychotic medications have considerable limitations. We would expect that enhanced availability of evidence-based psychosocial treatments would improve the overall effectiveness of treatment and promote recovery.

Perhaps the most important finding from the present report is that, even in randomized clinical trials, there can be biases in estimates of treatment response because of differences in the study participants’ exposures to treatment prior to the trial, and that random assignment to treatment condition alone is not a sufficient safeguard to eliminate this bias. For example, as demonstrated in these analyses, comparisons of medication effectiveness need to take into account whether medications being compared were each newly initiated.