Depressive disorders are common among opiate abusers

(1–

6). Depression is a frequent internal cue triggering drug craving

(7,

8). As comorbid depression is associated with continued drug use, it has been hypothesized that depression is also associated with continued HIV risk-taking through sharing of drug equipment

(9,

10). Higher scores on measures of psychological distress, inventories measuring symptoms of depression, and composite measures of depression, anxiety, and hostility have been associated with higher levels of injection-related risk taking

(11–

14).

Within the last 10 years, nearly half of the new cases of HIV infection in the United States have been among injection drug users

(15). Because measures for reducing the occurrence of AIDS associated with injection drug use include encouraging safer injecting practices, depression might have considerable influence as a modifiable factor. Previous reports linking depressive symptoms with injection risk behaviors have lacked diagnostic assessments and have not considered the severity of the depressive symptoms

(9–

14). This study examines the association of depression severity and injection risk behaviors in a cohort of active drug injectors.

Results

The majority of the 109 subjects were male (N=69, 63.3%) and Caucasian (N=89, 81.7%). The subjects’ mean age was 36.56 years (SD=8.82), and 10% were HIV positive. The subjects had been injecting drugs for an average of 13.5 years (SD=10.3), and 91% (N=99) reported heroin as their primary injection drug. Injection frequency was not correlated with depression severity (r=0.08, N=109, p=0.40). Just over half of the subjects (N=55; 50.5%) used benzodiazepines, and 61.5% (N=67) reported having used noninjection cocaine. A majority (N=69, 63.3%) of the subjects reported contact with one or more drug treatment modalities in the past 3 months. The mean score on the modified Hamilton depression scale was 20.97 (SD=3.93, range=14–34).

During the 90-day reporting period, subjects reported injecting drugs on an average of 68.92 days (SD=26.03, median=82.00) and averaged 258.73 total instances of drug injection (SD=203.30, median=225.00). The mean number of reported injection risk instances in the past 90 days was 57.51 (SD=134.72, range=0–750). Of the 109 subjects, 31.2% (N=34) reported no injection risk behavior, 26.6% (N=29) reported one to five instances of risk behavior, 27.5% (N=30) reported six to 89 instances, and 14.7% (N=16) reported 90 instances or more.

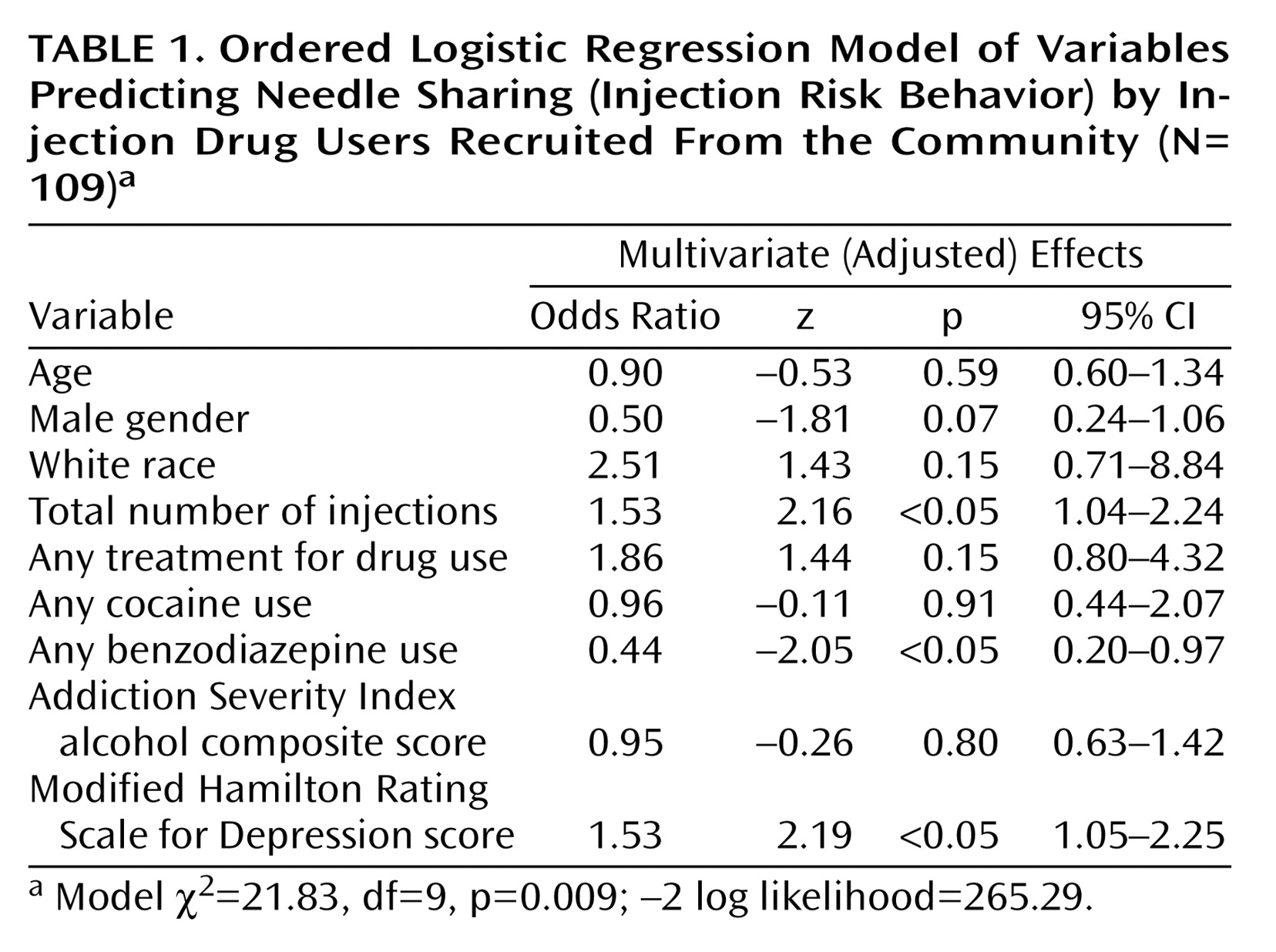

To control for potential confounding, we estimated a model with all nine selected predictor variables (

Table 1). The magnitude of the adjusted association between injection risk behavior and the modified Hamilton depression scale score was 1.53 (z=2.19, p<0.05). Because of concerns about the small number of subjects, we used bootstrap resampling (200 repetitions) to estimate empirically based standard errors for the adjusted effect of the modified Hamilton depression scale score; the results were consistent with those reported in

Table 1 (z=2.34, p<0.05). After adjustment for other covariates, an increase of one standard deviation in the total number of injections increased the cumulative odds of injection risk behavior by a factor of 1.53 (z=2.16, p<0.05), and benzodiazepine use was associated with lower odds of injection risk behavior (odds ratio=0.44, z=–2.05, p<0.05). Other covariates were not statistically significant predictors of injection risk.

Discussion

Identifying and attempting to modify the predictors of risky injection behavior is one approach to the prevention of transmission of blood-borne viruses. In this study of depressed drug injectors, we found that greater severity of depression was associated with increased sharing of needles and syringes, placing users at risk for HIV and hepatitis. These findings clarify the independent effect of psychiatric severity relative to other sociodemographic factors and frequency of drug injection.

While injection frequency was associated with greater injection risk, depression did not increase injection frequency in the subjects in our study. There are alternative mechanisms by which depression may increase risk taking. First, psychological factors may influence an injector’s perception of the threat posed by an infectious disease, and depression may engender fatalism about HIV, a form of passive suicidal behavior. Second, depression has been reported to be significantly and negatively correlated with drug users’ confidence in giving careful thought to the consequences of life decisions

(25); depression could thereby lower the likelihood of taking preventive action. Third, depression may affect an individual’s attention, promoting carelessness in drug use activities. Fourth, depression may index a lesser ability to cope with stressful life events, leading to higher levels of unmindful sharing of drug equipment. Fifth, depression may be serving as a marker of additional psychiatric diagnoses, such as anxiety disorders, that have been associated with drug injection risk

(14). Finally, more depressed injectors may report more risk than would objectively be observed.

The subjects in this study included only injection drug users who met the DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder(63%), dysthymia (2%), major depressive disorder plus dysthymia (17%), or persistent substance-induced mood disorder (17%). A significant challenge in the study of depression in opiate users is that opiate use may induce transient symptoms that are difficult to distinguish from the symptoms of primary mood disorders

(26,

27), despite recent attempts to develop distinctive diagnostic criteria and interview instruments. Previous studies of the association of mood and injection risk taking have assessed only depressive symptoms but have not used formal diagnostic criteria. Symptom scores are likely to be less stable than diagnoses. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that the dichotomous diagnostic approach to depression may not capture the association with HIV risk behaviors that a continuous measure such as the modified Hamilton depression scale offers. It is noteworthy that our study did not include a group of nondepressed injectors who may have a lower frequency of risky injection behavior

(9–

14), and, as in most studies of injection drug users, the measurement of injection behavior was based on self-report. Finally, although the number of subjects was small, the community-based recruitment and the use of robust standard error estimators should add to confidence in the findings.

Benzodiazepine use was related to a lower rate of injection risk taking, in contrast to the findings of previous studies in which benzodiazepine use was associated with higher rates of injection risk

(19,

28). In these previous studies, benzodiazepine use may have been a marker for a particularly dysfunctional subgroup of polydrug users rather than an agent of risk taking. We speculate that for the drug injectors with a diagnosis of depression who were the subjects in our study, benzodiazepine use may have been a marker of social isolation, which allowed fewer opportunities to share drug equipment.

All injectors who have a current axis I diagnosis of depression should be candidates for treatment. The obvious clinical implication of the association reported here is that if depression severity can be reduced, the rate of high-risk injection behaviors may also be reduced. Comorbid depression and substance use are interactive and mutually maintaining. If untreated, depression affects readiness to modify risk behaviors, a basic component of behavioral change; thus, treatment of depression may advance readiness to change. Regardless of the causal relationship that underlies the association of major depression and needle-sharing, risk reduction programs targeted at injection drug users need to be designed with an awareness of the role of psychiatric disorders.