Body dysmorphic disorder is distressing, impairing, and relatively common

(1,

2). Many patients require hospitalization, become housebound, or attempt suicide

(1,

2). Although serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) are often efficacious

(2–

4), most patients do not respond or respond only partially. However, no placebo-controlled studies of augmentation of SRIs for the treatment of body dysmorphic disorder have been done. Furthermore, although 40%–50% of patients are delusional

(1,

2), thereby qualifying for a diagnosis of delusional disorder in addition to body dysmorphic disorder, no studies of antipsychotic medications have been done for these patients.

Pimozide was selected as an SRI augmentor because antipsychotics have been widely recommended and used for body dysmorphic disorder

(5,

6), despite a lack of research examining their efficacy. Pimozide has been proposed to be uniquely effective for disorders characterized by somatic delusions (monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychoses), including body dysmorphic disorder

(5,

6). Also, pimozide effectively augments SRIs in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

(7), which has similarities to body dysmorphic disorder.

Method

Twenty-eight patients were included in the study. These subjects had received fluoxetine for ≥12 weeks, reaching 80 mg/day if tolerated (mean=62.5 mg/day, SD=20.1). Nineteen of these patients received fluoxetine in a separate placebo-controlled study (4); 16 did not respond to fluoxetine, and the three responders still had severe enough body dysmorphic disorder to participate in this pimozide study. Nine of the patients received the fluoxetine in my practice. An additional 16 patients in the separate placebo-controlled fluoxetine study (13 nonresponders and three responders), plus two nonresponders from my clinical practice, did not enter the pimozide study for different reasons (e.g., lack of interest).

The 28 patients were randomly assigned to 8 weeks of double-blind pimozide (N=11) or placebo (N=17) augmentation while remaining on a fixed fluoxetine dose. Pimozide and placebo were furnished in identical-appearing tablets (2 mg for pimozide). Subjects were started on 1 mg/day, with an attempt made to raise the dose to 2 mg/day after 1 week and then by 2 mg per week to a maximum of 10 mg/day if tolerated. After a complete description of the study, written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria were standard for efficacy studies (e.g., reference

4). Following fluoxetine treatment, subjects had a body dysmorphic disorder score of ≥20 on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Body Dysmorphic Disorder (8) with fair, poor, or absent insight and were at least moderately ill according to the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale. Subjects took no other psychotropics. They could not begin psychotherapy during the study or have begun it within the past 4 months. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Body Dysmorphic Disorder score was the primary outcome measure; a decrease in score of ≥30% determined treatment response

(8). The Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale

(9) assessed delusionality of appearance beliefs and categorized subjects at baseline as delusional (N=12) or nondelusional (N=16) according to an empirically derived cutoff point. Other measures were the CGI, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, and Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R.

Excluding the augmented fluoxetine trial, 18 (64.3%) of the 28 subjects had previously received a total of 58 psychotropic medications. Fifteen subjects received a total of 26 SRIs, and three received a neuroleptic (one trial each). Only two SRI trials improved body dysmorphic disorder, but only five trials were considered minimally adequate for body dysmorphic disorder

(2), one of which led to improvement. Three non-SRI medications (a non-SRI tricyclic, lithium, and a neuroleptic) improved body dysmorphic disorder.

Analyses were based on the intent-to-treat study group and used analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with baseline measures as the covariate. The effect size (d) was based on ANCOVA. Continuous variables were analyzed with independent-sample t tests, and dichotomous variables were analyzed with chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test. All tests were two-tailed; the alpha level was 0.05.

Results

Baseline age, gender, and body dysmorphic disorder severity did not significantly differ between groups, although the pimozide group were younger at the onset of body dysmorphic disorder (mean=13.7 years, SD=3.1, versus mean=20.4, SD=8.6) (t=2.5, df=26, p=0.02) and had had body dysmorphic disorder for a longer time (mean=21.2 years, SD=10.8, versus mean=12.4, SD=10.1) (t=–2.1, df=25, p=0.04). Thirteen (76.5%) of the 17 patients given placebo and six (54.5%) of the 11 given pimozide completed the study (eight [72.7%] of the pimozide subjects completed ≥4 weeks). The mean endpoint pimozide dose was 1.7 mg/day (SD=1.0); the equivalent dose in the placebo group was 5.0 mg/day (SD=3.4).

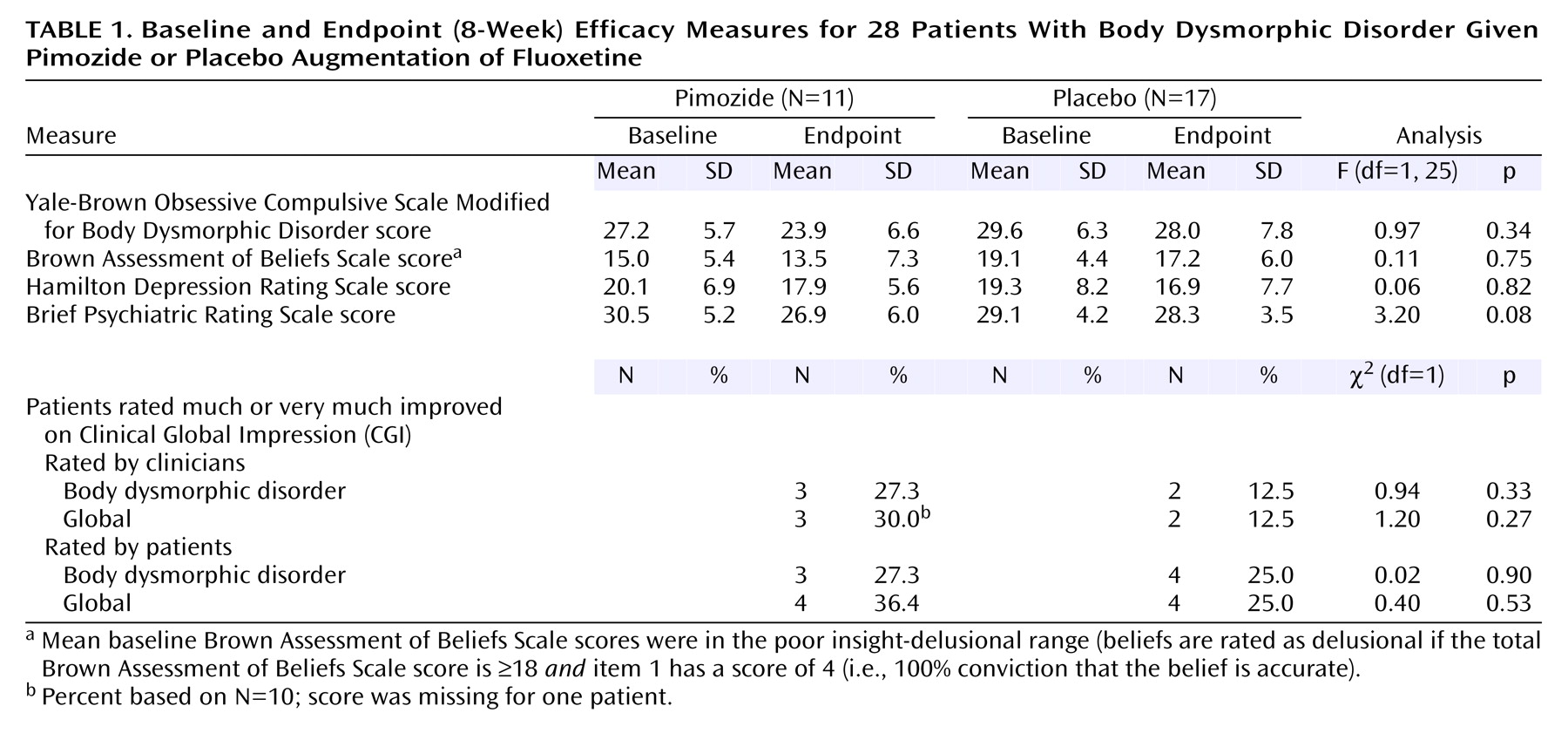

Pimozide was not more efficacious than placebo for body dysmorphic disorder severity or on any other measure (

Table 1). Mean scores on the 48-point Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Body Dysmorphic Disorder decreased only 1.7 points more with pimozide than placebo. The effect size (d) was 0.23. Two (18.2%) of 11 subjects responded to pimozide and three (17.6%) of 17 responded to placebo (χ

2=0.001, df=1, p=0.97). There was no significant effect of baseline delusionality on endpoint body dysmorphic disorder severity (F=2.9, df=1, 25, p=0.10). One (8.3%) of the 12 delusional patients responded (this patient responded to placebo), and four (25.0%) of the 16 nondelusional patients responded (two to pimozide and two to placebo). Delusionality did not decrease more with pimozide than placebo (F=0.11, df=1, 25, p=0.75). The only adverse event more frequent with pimozide was difficulty sitting still (54.6% [N=6] versus 0%) (p=0.001, Fisher’s exact test). No serious adverse events occurred.

Discussion

Although pimozide has been proposed to be effective for body dysmorphic disorder

(5,

6), it was not more efficacious in augmenting fluoxetine and did not improve delusionality more than placebo. Because power was limited, these results are preliminary. Power to detect a medium effect size (d=0.50) was 25%, and power to detect a large effect size (d=0.80) was 53%. Nonetheless, the pimozide response rate was very low and similar to that of placebo. The mean group difference in improvement score on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Body Dysmorphic Disorder was not clinically meaningful. A sample of more than 600 subjects would be needed to yield a statistically significant result with the effect size obtained.

Studies

(1–

4) have found similarities between body dysmorphic disorder’s delusional and nondelusional forms, suggesting they may be the same disorder. This study offers some support for this, given the similar pimozide response rate in both groups. It is unclear why pimozide augmentation is efficacious for OCD

(7) but not for body dysmorphic disorder in this study, especially because body dysmorphic disorder patients are more delusional

(2). Possible explanations include this study’s low power, the fairly modest mean pimozide dose attained (1.7 mg/day versus 6.5 mg/day, SD=5.4, in OCD

[7]), and possible treatment refractoriness of the body dysmorphic disorder patients. Furthermore, studies of augmentation of SRIs with pimozide and haloperidol in patients with OCD found higher response rates in those with a tic disorder (100% versus 33%)

(10) or a tic disorder or schizotypal personality disorder (88% versus 22%)

(7). No body dysmorphic disorder subject had either diagnosis. In addition, body dysmorphic disorder and OCD have other differences and are probably not identical disorders

(2). Additional studies of augmentation of SRIs, including studies with atypical antipsychotics, are greatly needed in body dysmorphic disorder, given the paucity of empirically based treatments for this often-disabling disorder.