Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common neuropsychiatric disorder in childhood that often persists into adulthood. Approximately 15% of patients still meet full ADHD criteria according to DSM-IV in adulthood, and 40%–60% remit only partially and have increased symptom counts (

1). Despite substantial heritability, as shown by adoption and twin studies (

2), identifying genes for ADHD has proven difficult (

3,

4). Only a handful of susceptibility genes have been identified to date, all of which increase ADHD risk with only small effect sizes (

4). This polygenic heritability—together with the heterogeneity of the ADHD clinical phenotype—is a complicating factor in the identification of ADHD genes. However, information on the function of those genes known to be associated with ADHD could help us identify the biological mechanisms underlying the disorder.

Understanding associations between genes and a complex disorder like ADHD may be made easier if the disorder is decomposed into intermediate phenotypes such as neurocognitive measures. Conceivably, fewer genes will play a role in one of these intermediate neurocognitive phenotypes than in the entire clinical phenotype. Besides the well-known executive function problems, patients with ADHD often display abnormal sensitivity to reward (

5), as evidenced by steeper temporal discounting rates, altered decision making, and an aversion to delay of gratification in reward-related tests (

6–

9). Temporal discounting is the patient's preference to receive smaller rewards sooner rather than larger rewards later and is postulated to be an intermediate phenotype for impulsivity. Neuroimaging studies have shown engagement of alternative brain regions in decision making in ADHD patients (

10). A prominent feature is hypoactivation of the ventral striatum, a brain area with an important role in reward processing (

11,

12), during reward anticipation (

13,

14). Ventral striatal activity is also associated with impulsivity, a hallmark of ADHD (

12,

13).

Recently, the

NOS1 gene was identified as a candidate gene for ADHD and other impulsivity disorders (

15). A variant in this gene was also among the top findings of a genome-wide association study in ADHD (

3).

NOS1 encodes nitric oxide synthase 1. Nitric oxide, the product of this enzyme's activity, acts as the second messenger downstream of the

N-methyl-

d-aspartate receptor and interacts with both the dopaminergic and serotonergic systems in the human brain. Nitric oxide inhibits monoamine transporters, thereby modulating the dopamine and noradrenalin concentration in the extracellular space (

16). In addition,

NOS1 functions in neurite outgrowth, suggesting an early influence on brain development (

17).

Located on chromosome 12, the

NOS1 gene has a complex structure, consisting of 28 protein coding exons, with 12 alternative untranslated first exons referred to as exons 1a–1l. In exon 1f, a variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) polymorphism that alters gene expression is present (

15). This exon has a relatively high expression in the brain, with high specificity for the basal ganglia, including the striatum. Since

NOS1 modulates tonic extracellular dopamine levels and phasic dopaminergic neuron spike activity, it might affect disorders with deficient striatal functioning (

18). Targeted disruption of

Nos1 in mice increased impulsivity and aggressiveness, reduced anxiety, and impaired learning (

19,

20). Human behavioral and imaging studies have shown

NOS1 exon 1f-VNTR to be associated with hyperactive, impulsive, and aggressive behavior as well as hypofunctioning of the anterior cingulate cortex (

15,

21,

22).

Although the NOS1 gene has been linked to ADHD, impulsivity, and modification of neurotransmitter levels in the striatum, effects of NOS1 genetic variation on striatal activity have not been investigated. The objective of the present study was to better understand the effect of this gene on neurobiological dysfunctioning in adult ADHD by exploring the influence of the exon 1f-VNTR on impulsivity and reward-related striatal activity in a large sample of adult ADHD patients (N=87) and healthy comparison subjects (N=49). Given the results of previous studies, we expected to find 1) higher impulsivity scores as well as 2) ventral striatal hypoactivation in ADHD patients relative to healthy comparison subjects, 3) increased impulsivity in homozygous carriers of the NOS1 exon 1f-VNTR short allele, and 4) modulation of ventral striatal activity by the exon 1f-VNTR.

Method

Participants

One hundred and 36 individuals (adult ADHD patients, N=87; healthy comparison subjects, N=49) from the Dutch cohort of the International Multicenter persistent ADHD CollaboraTion (IMpACT [

23]) participated in the present study. All participants underwent endophenotypic tests for adult ADHD in which cognitive functioning and neuroimaging data were collected. The ADHD patients and an age-, gender-, and IQ-comparable group of healthy subjects were recruited from the department of Psychiatry of the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre (Nijmegen, the Netherlands) and through advertisement. Patients were included if they met DSM-IV-TR criteria for ADHD in childhood as well as adulthood. All participants were assessed using the Diagnostic Interview for Adult ADHD (

24). This interview focuses on the 18 DSM-IV symptoms of ADHD and uses concrete and realistic examples to thoroughly investigate whether a symptom is currently present or was present in childhood. In order to obtain information about ADHD symptoms and impairment in childhood, additional information was acquired from parent and school reports whenever possible. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I) was used for comorbidity assessment. Assessments were carried out by trained professionals (psychiatrists or psychologists). In addition, a quantitative measure of clinical symptoms was obtained using the ADHD Rating Scale-IV (

25).

Exclusion criteria for participants were psychosis, alcohol or substance addiction in the last 6 months, current major depression (assessed using SCID-I), full-scale IQ estimate <70 (assessed using the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III), neurological disorders, sensorimotor disabilities, non-Caucasian ethnicity, and medication use other than psychostimulants or atomoxetine. An additional exclusion criterion for healthy comparison subjects was a current or past neurological or psychiatric disorder according to SCID-I. Twenty-eight patients were medication-naive at the time of the trial. Patients who were receiving treatment with ADHD medication (methylphenidate [N=44], atomoxetine [N=4], and dextroamphetamine [N=11]) were asked to withhold use of their medication 24 hours prior to testing. As a result of excessive movement during scanning (N=4), metal in the body or tattoos (N=25), and technical problems (N=3), the final sample size for the imaging part of the study was 104 (ADHD patients, N=63; healthy comparison subjects, N=41). This final sample included 19 medication-naive patients; 26 ADHD patients and 18 comparison subjects in this subsample were men. Participants had to refrain from smoking prior to and during testing (

26). Indirect effects of smoking were controlled for by taking smoking habits (yes/no) into account in the analysis. This study was approved by the regional ethics committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Genotyping

Genotyping of the exon 1f-VNTR was performed by sequence-length analysis on a genetic analyzer (see the data supplement accompanying the online version of this article). The resulting genotypes were converted to short (S) and long (L) alleles. The homozygous short allele (short-short [SS]) genotype has been identified as a risk factor for psychiatric disorders (

15), and therefore genotypes were stratified into an SS carrier group and a group of participants carrying at least one long allele (short-long [SL]/long-long [LL]) for the behavioral and functional data analyses.

Behavioral Task: Reward-Related Impulsivity

The delay discounting task (

27) was administered to measure reward-related impulsivity. On each trial of this task, participants had to choose between varying amounts of hypothetical immediate rewards and hypothetical delayed rewards. A total of 110 questions (such as, “Which do you prefer: 30 euro 180 days from now or 2 euro now?”) were displayed on a screen. In successive questions, the amount of immediate money was increased until it equaled the delayed reward. This way, the personal point of indifference, where two options have equal subjective value to an individual, was determined for every participant. Indifference points were determined for three delayed reward conditions (10, 30, and 100 euros) and five different delays (2, 30, 180, 365, and 730 days). By using a discount function, an impulsivity parameter (

k) could be derived. Previous studies have shown that discounting curves fit well with hyperbolic functions (

28). The discount function for the task was as follows:

V=

a/(1+

kD). For this equation, “

V” represents the present value of the delayed reward, in this case the indifference point, and “a” represents the delayed reward (10, 30, or 100 euro) at delay “

D” (2, 30, 180, 365, or 730 days). Higher levels of

k correspond to steeper discounting rates and higher levels of impulsivity (

29). The main outcome measure was the average k for 10 euro (

k10), 30 euro (

k30), and 100 euro (

k100) and the average score of all trials (

kall). A logarithmic transformation was performed to normalize

k values (log

k).

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) Reward Anticipation Paradigm

To examine neural responses to reward anticipation, participants were scanned while performing a modified monetary incentive delay task, which has been shown to induce ventral striatal activity (

30) (see the data supplement). Participants were asked to respond as quickly as possible to a target by pressing a button. Prior to display of this target, a cue (duration: 3.5–8.5 seconds) was given to indicate whether a reward could or could not be obtained. After each target response, the outcome was displayed. Participants could gain 1 euro in the reward condition and no money during the no-reward condition if they responded between 270 msec and 500 msec after target onset. This response window was individually adjusted (see the data supplement). The task consisted of a practice trial, after which the purpose of the task was again briefly summarized, followed by 50 trials in which reward and no-reward cues were randomly displayed. The experiment lasted 12 minutes, and a total of 12 euro could be gained. At the end of the experiment, the awarded money was shown on the screen and transferred to the participant's bank account. Reaction times in the reward and no-reward condition were the behavioral outcome measures.

Behavioral Analysis

Reward-related impulsivity.

To assess the effects of ADHD status (ADHD patients relative to healthy comparison subjects) and NOS1 genotype (SS versus SL/LL) on reward-related impulsivity, analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were carried out using log(k10), log(k30), log(k100), and log(kall ) as dependent variables, and age and gender were incorporated as covariates. Cohen's d was calculated to identify effect size.

Monetary incentive delay task.

A repeated-measures general linear model was performed to assess the effect of cue (reward/no-reward) on response time. This general linear model was carried out with reaction time as the dependent variable and cue as the within-subject variable. The between-subject factors ADHD status and NOS1 exon 1f-VNTR genotype were added to the general linear model to identify group effects of cue-induced reaction times. Cohen's d was also calculated.

fMRI Analysis

After preprocessing (for details on fMRI acquisition and preprocessing, see the data supplement), first-level analyses were performed for each participant to estimate eight parameters of interest with a general linear model for the “cue,” “target,” “hit,” and “miss” events in both the reward and no-reward conditions. These events were modeled as event-related regressors, with a zero duration, and convolved with the canonical hemodynamic response function in SPM5. Additionally, realignment parameters were included to account for movement-related variability, and time-derivatives were used, which resulted in 14 additional regressors of no interest. Data were high-pass filtered using a frequency cutoff of 1/128 Hz.

To assess neural activity associated with reward anticipation, our contrast of interest concerned the reward and no-reward cue events. The contrast images for these events were submitted to a second-level random effect analysis, with the following full factorial 2×2×2 design: ADHD status,

NOS1 genotype, and cue (reward versus no-reward). Age and gender were included as covariates (

31,

32). For the whole-brain analysis, the main effect of cue was tested using a threshold of p<0.05 (family-wise error-corrected) and a cluster size threshold of 35 voxels. Because of our a priori hypothesis regarding the ventral striatum, the resulting suprathreshold ventral striatal region in the whole-brain analysis of the main effect of cue was defined as our region of interest. Defining this functional region for two groups with proven differential ventral striatal activity (such as ADHD patients and healthy comparison subjects [

13,

14]) bears the risk of bias if the two groups are not equal in size (for details see reference

33). To prevent any selection bias in our study (in which the patient group was bigger), we separately defined functional ventral striatal region for each diagnostic group and analyzed both groups to assess the effect of genotype. Cluster beta weights were extracted from these regions using the MarsBaR toolbox (

34). To replicate previous studies on striatal hypoactivation in ADHD patients, a one-sided ANOVA was performed, with ADHD status as an independent variable and ventral striatal activity as a dependent variable. Pearson's correlations between ventral striatal activity and impulsivity were calculated. All statistical tests were two-sided, unless stated otherwise.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the study sample are presented in

Table 1. There were no significant differences between groups based on ADHD status or

NOS1 exon 1f-VNTR genotype with respect to gender, age, or IQ. ADHD patients and healthy comparison subjects showed the expected differences in self-reported ADHD symptoms (p<0.001) and an equal distribution of not otherwise specified exon 1f-VNTR genotype. Fifty-four patients fulfilled criteria for the combined ADHD subtype; 20 fulfilled criteria for the inattentive subtype; and 13 were characterized as hyperactive/impulsive. Within the patient group, medication use was equally distributed over the genotype subgroups (SS, SL/LL), with no differences in disease severity between medicated and never-medicated patients. A similar distribution of characteristics was observed in the subsample of participants that underwent fMRI. In this subsample, 42% of ADHD patients and 24% of healthy comparison subjects were smokers, and smoking was equally distributed over the genotype groups (SS: 47%; SL/LL: 32%).

Behavioral Results

Reward-related impulsivity.

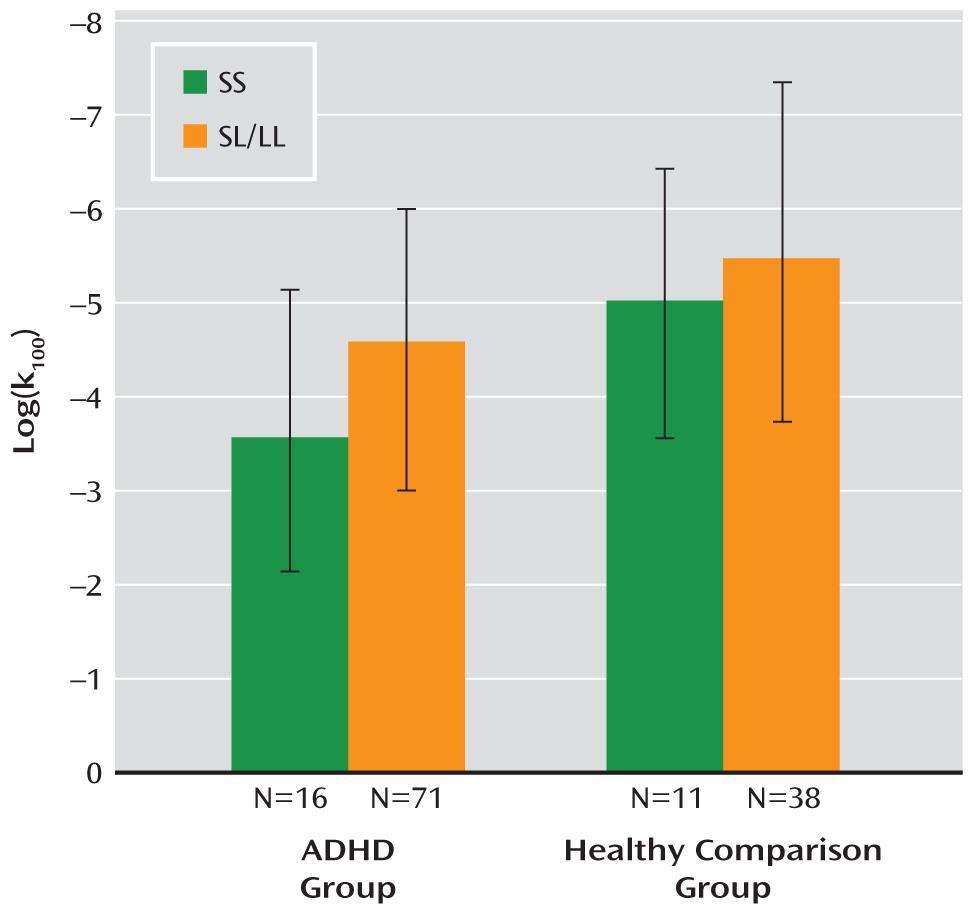

ADHD patients showed higher levels of reward-related impulsivity than healthy comparison subjects on the delay discounting task (log(

kall): F=7.15, df=1, 134, p=0.008). The strongest effect was found in the

k100 condition in which the largest amount of money (100 euro) was discounted (p<0.0001). Log(

k100) was not significantly correlated with ADHD severity. In the ADHD group, patients with the SS genotype had higher reward-related impulsivity scores than those with SL/LL genotypes (F=4.73, df=1, 85, p=0.03, Cohen's d=0.60) (

Figure 1). In the comparison group, the effect of genotype did not reach significance. No interaction of diagnosis and genotype was observed. Within the ADHD group, impulsivity was not significantly correlated with ADHD severity (number of ADHD symptoms).

Modified monetary incentive delay task.

A main effect of cue on reaction time was found for the monetary incentive delay task (F=165.54, df=1, 104, p<0.0001). As expected, participants reacted faster in reward trials (mean response time: 243 msec) than in no-reward trials (mean response time: 284 msec) (

Table 2). ADHD diagnosis,

NOS1 genotype, or the interaction of both these factors did not affect cue-induced reaction time.

Functional Imaging Results

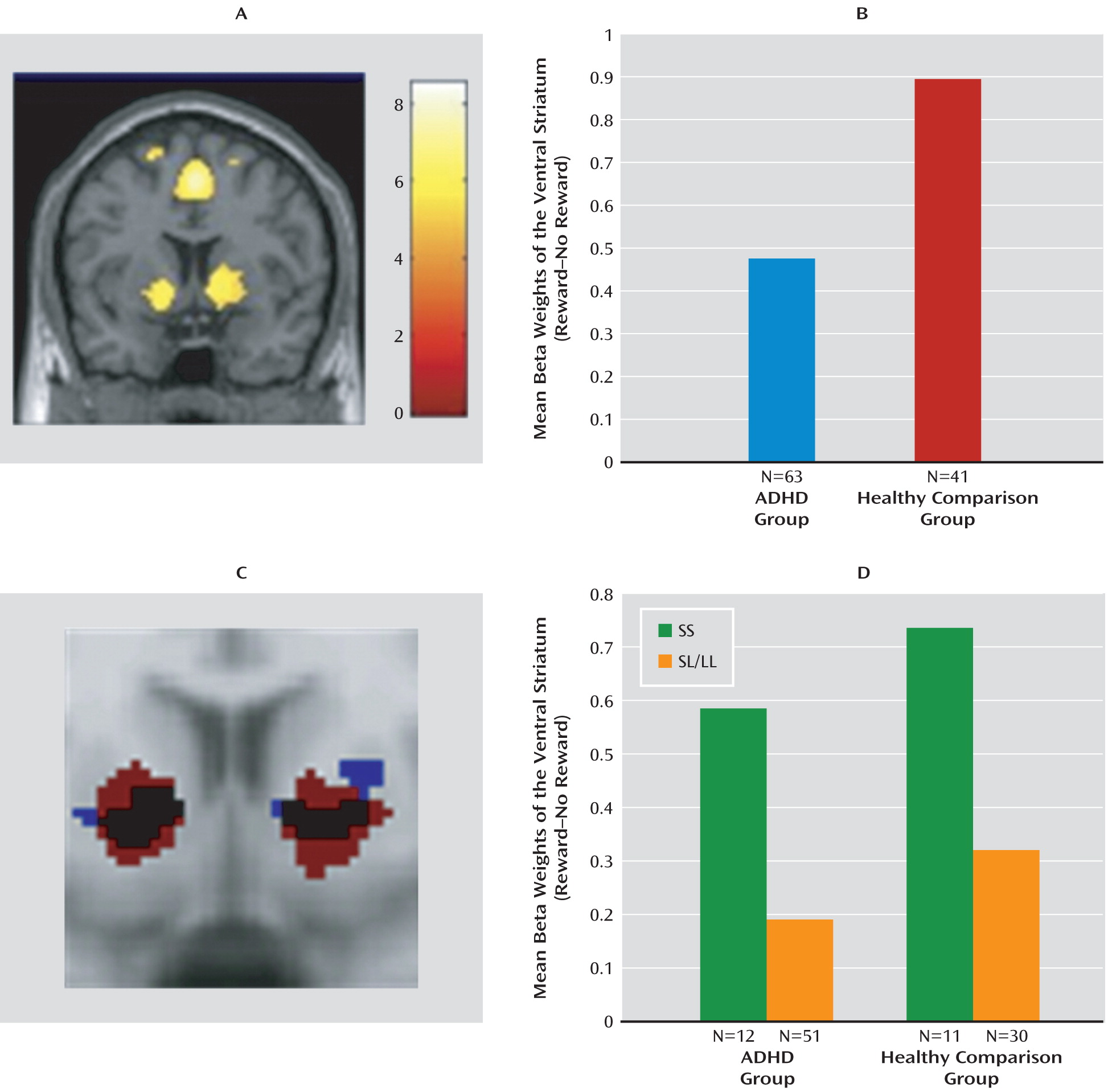

Brain regions activated in the “reward cue>no-reward cue” contrast are shown in

Figure 2 (also see the data supplement). In the whole-brain analysis of the bilateral ventral striatum, the lateral prefrontal cortex, insula, left putamen, and left middle frontal gyrus were activated. Further analysis focused on bilateral ventral striatal activity.

Reward-related ventral striatal activity.

Bilateral average cluster activity in the ventral striatum for both the patient and comparison groups is shown in

Figure 2. ADHD patients had lower ventral striatal activity than healthy comparison subjects during reward anticipation (F=3.43, df=1, 102, p=0.03), confirming findings in previous studies (

13,

14).

The functional region of interest that was defined based on striatal activity observed in the ADHD group (

Figure 2) showed a significant effect of

NOS1 genotype (F=4.75, df=1, 61, p=0.03, Cohen's d=0.81); this same effect was seen in analysis based on the functional region of interest defined by activity in healthy comparison subjects (F=11.45, df=1, 39, p=0.002, Cohen's d=1.03). For both definitions (in ADHD patients and healthy comparison subjects), carriers of the SS genotype showed higher activity than SL/LL genotype carriers (

Figure 2).

Ventral striatal activity did not differ between medicated and medication-naïve patients, nor was an effect of smoking observed among either patients or healthy comparison subjects.

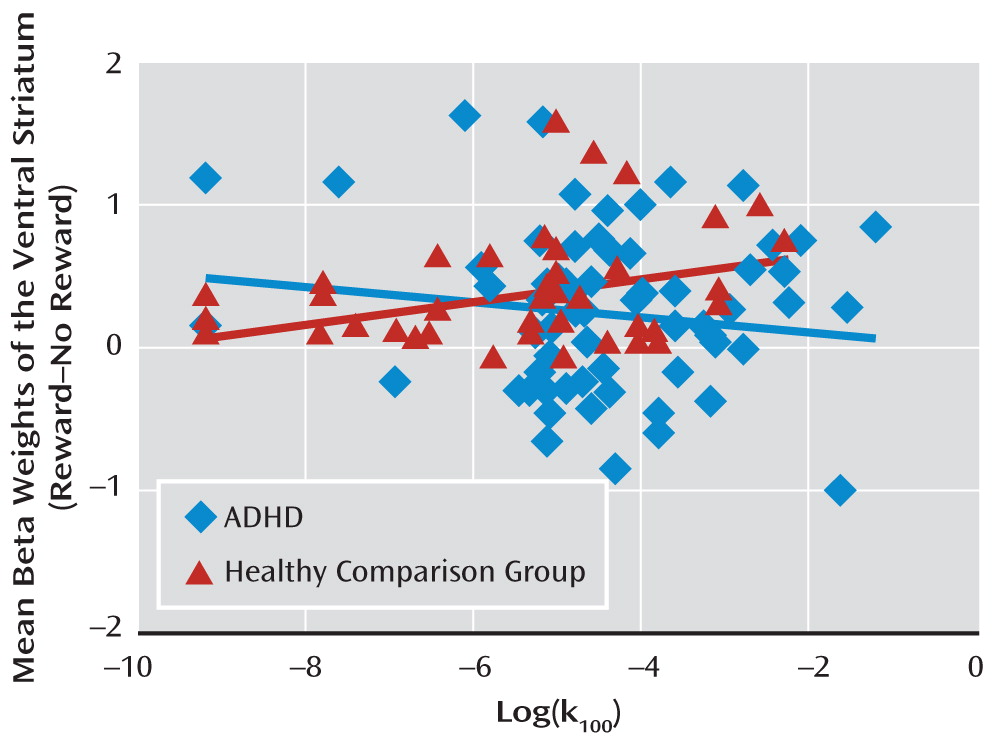

Correlation between ventral striatal activity and impulsivity.

The correlation between ventral striatal activity and impulsivity in healthy comparison subjects (r=0.31, p=0.04) was significantly different (p=0.04) from the correlation in ADHD patients (

Figure 3).

Discussion

The

NOS1 exon 1f-VNTR genotype influenced reward cue-related ventral striatal activity in the participants of this study, with the same direction of effect in both the ADHD and comparison groups. Genotype also modulated reward-related impulsivity levels in ADHD patients. The effect of the

NOS1 genotype on reward-related impulsivity in the healthy comparison group was similar but did not reach statistical significance. A smaller subgroup with the short allele (N=11) may account for this failure to detect significance. The observed association of the

NOS1 genotype with reward-related impulsivity in ADHD patients replicates earlier findings in patients with impulse-control disorders compared with healthy subjects (

21,

22). Our results now extend the effect of the

NOS1 genotype to ventral striatal activity, a critical component of the underlying neurological substrate of impulsivity (

35).

The role of

NOS1 in reward-related impulsivity, observed in the behavioral analysis of this study as well as in several psychiatric disorders and the general population (

3,

15,

22,

36), suggests that the association of this gene with clinical phenotypes such as ADHD is mediated by its effect on this behavioral trait. Additionally, our finding that the genotype subgroup linked with higher reward-related impulsivity is associated with higher activity of the ventral striatum (which is consistent with previous research [

35]) corroborates

NOS1's role in impulsivity, since we now show that reward-cue-related impulsivity is positively correlated with ventral striatal activity in healthy subjects.

What appears discordant is the combination of increased ventral striatal activity in more impulsive healthy individuals with the reduced reward-related ventral striatal activity and no significant correlation with impulsivity in patients with ADHD, a disorder for which increased impulsivity is a hallmark (

12,

13). For healthy individuals, our findings match those of an earlier study conducted by Hariri et al. (

35), where impulsivity as measured by the delay discounting task was found to be positively correlated with ventral striatal activity. However, earlier studies with sample sizes smaller than that of our study reported a negative association in ADHD patients (

13,

14).

Given the differences in findings for ventral striatal activity in ADHD patients and healthy individuals, one might have expected to observe a differential

NOS1 genotype effect in the two groups or a gene-by-disorder interaction, as Durston et al. (

37) found for the

DAT1 gene. However, the finding of

NOS1 genotype effects in the same direction in both groups shows that the

NOS1 exon 1f-VNTR SS genotype related to ADHD does not contribute to ventral striatal hypoactivation in the disorder but acts on reward-related impulsivity. Thus, the ventral striatal hypoactivation in ADHD must be caused by something other than the

NOS1 gene. One could consider altered baseline dopamine levels in the striatum in ADHD (

38) as a possible explanation, since positive correlations between striatal dopamine and ventral striatal activity exist in healthy subjects (

39). In addition, the influence of other ADHD candidate genes such as the dopamine transporter gene (

DAT1/

SLC6A3) (

40), which is also associated with altered dopaminergic synthesis—or perhaps an altered connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and striatum (

41)—might play a role. Thus, one might hypothesize that the reduced ventral striatal activity is a compensatory mechanism to alleviate the effects of reduced prefrontal control.

Combined consideration of intermediate phenotypes, neurobiological mechanisms, and molecular genetic effects may therefore elucidate mechanisms contributing to the clinical symptoms of ADHD more completely than the analysis of any of these parameters in isolation. Consistent with these expectations, functional effects of the NOS1 exon 1f-VNTR genotype were more readily observed (i.e., higher effect size) in brain activity (Cohen's d range: 0.8–1.0) than at the behavioral level (Cohen's d range: 0.3–0.6), in accordance with the view that the former is more proximal to genes. Dissecting the clinical ADHD phenotype into relevant, measurable traits such as motivational deficits and assessing genetic effects on these traits on a neurobiological level are necessary steps to elucidate the biological mechanisms underlying the disorder.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Angelien Heister and Remco Makkinje for assistance with genotyping and Paul Gaalman for technical assistance with MRI scanning. The authors also thank all of the participants of this study.