Studies of populations in China (

1) and the Netherlands (

2) have demonstrated that maternal exposure to discrete periods of famine during pregnancy results in the birth of children who are twice as likely to develop schizophrenia or exhibit schizoid personality disorder than those who are not exposed. However, conditions that cause prenatal malnutrition may continue into the postnatal period and can be conceptualized as dimensional risk factors for physical and mental illnesses. The rate of postnatal growth may be considered as a continuum from fetal development (

3), and the growth trajectory from birth to 2½ years among female schizophrenia patients has been reported to be slower than that for comparison subjects (

4). In addition to birth disturbances, thinness in childhood (attributed to malnutrition) has been associated with later development of schizophrenia (

5). Furthermore, a study of 31-year-old women reported that both perinatal and postnatal disturbances are related to increased schizotypal traits in later life (

6). Surprisingly, however, there have been no studies, to our knowledge, of the relationship between malnutrition directly assessed postnatally and any schizophrenia spectrum disorder.

If poor nutrition is indeed a risk factor for schizotypal personality disorder, then an important question concerns whether this factor operates directly or whether a third factor mediates this relationship. A key requirement of a mediator is that it must relate to both the independent variable (malnutrition) and the dependent variable (schizotypal personality). One such possible candidate is low IQ, given its linkage with schizophrenia. Meta-analyses have demonstrated that children who later develop schizophrenia have lower IQs than comparison subjects (

7). In a study of Swedish Army recruits, individuals with low IQ had an increased risk of developing schizophrenia, and it was mainly a nonverbal test of mechanical ability that revealed this association (

8). The authors indicated that this test requires executive control, which in turn may be reliant on frontal lobe functioning. Furthermore, individuals with clinically assessed schizotypal personality disorder (particularly those with negative and disorganized features) have demonstrated poorer performance on the arithmetic subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (

9). Given these findings, IQ meets one criterion for status as a mediator.

While poor nutrition may be a risk factor for later development of schizotypal personality and IQ may be a possible mediator, one further unresolved issue is with regard to whether any relationship between malnutrition and schizotypy applies to all forms of schizotypy or whether such a relationship is specific to certain subfactors. One comprehensive review of schizotypal personality suggests that two fundamentally different forms of schizotypy exist (

12). One form, referred to as “neuroschizotypy,” is hypothesized to be a neurodevelopmental disorder, with its origins in genetic, prenatal, and early postnatal influences (including malnutrition), and consists of interpersonal and disorganized subfactors of schizotypal personality (

13). A second form, referred to as “pseudoschizotypy,” is hypothesized to have origins in psychosocial adversity, including childhood abuse and neglect, and consists of the cognitive-perceptual features of schizotypal personality. Given this model, it might be expected that malnutrition would be relatively more associated with interpersonal and disorganized features rather than cognitive-perceptual features.

In this study, we used a prospective, longitudinal design assessing nutrition, IQ, and schizotypy in order to establish a temporal ordering between these variables and to assess the mechanisms of action. We hypothesized that 1) poor nutrition at age 3 would be associated with lower IQ at age 11, 2) low IQ at age 11 would be associated with increased schizotypy at age 23, 3) poor nutritional status at age 3 would be associated with higher rates of schizotypal personality at age 23, particularly with respect to cognitive-perceptual and disorganized features, and 4) this latter relationship would be mediated by low IQ.

Results

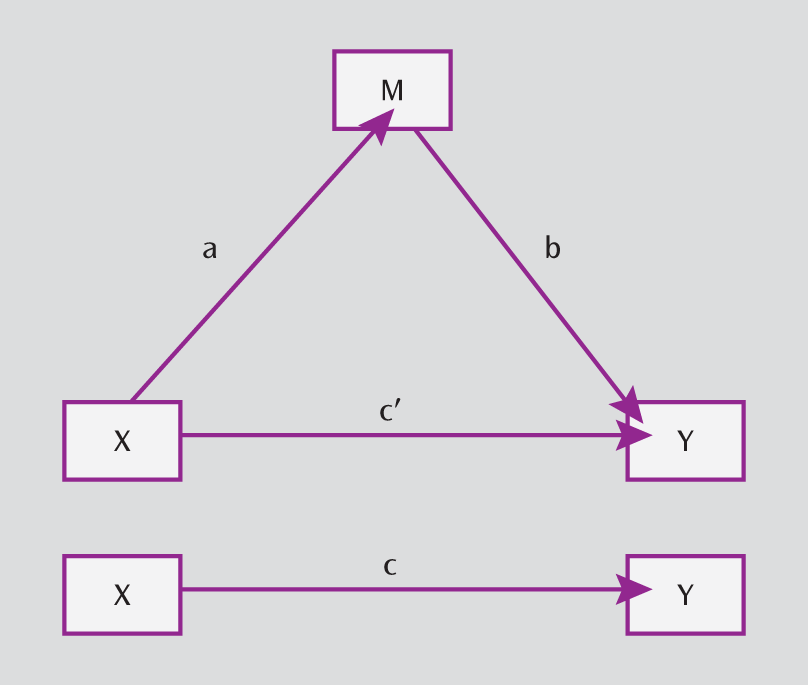

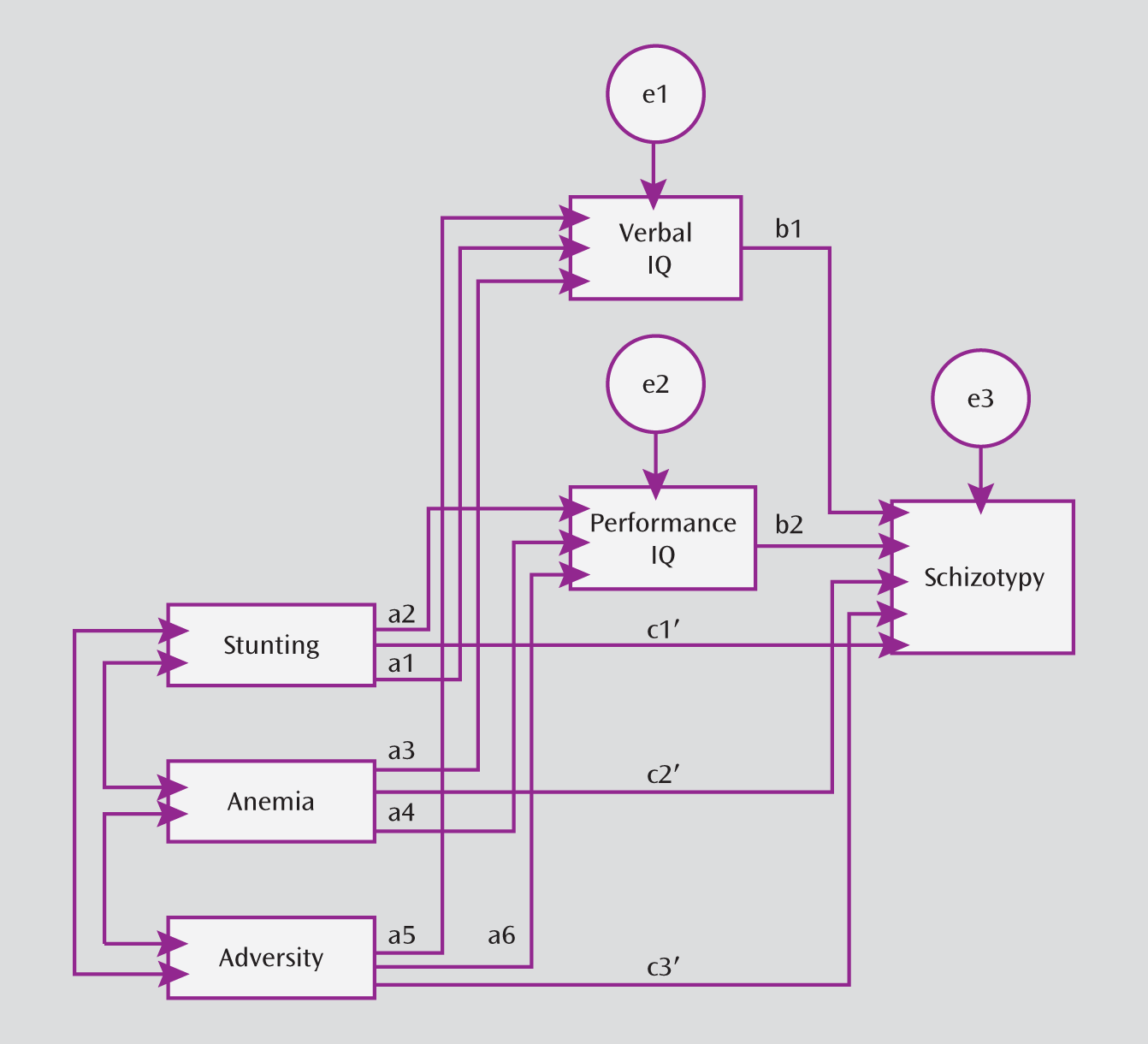

Analyses were aimed at establishing 1) the candidacy of IQ as a potential mediator of the relationship between malnutrition and schizotypy and 2) whether the extent of any mediation was full or partial. The beta weights for the regression slopes of IQ on malnutrition (pathway a) are listed in

Table 3. Across gender, all regressions were statistically significant for both indicators of malnutrition (stunting and anemia). Negative slopes indicated that increased malnutrition was associated with low verbal and performance IQ. Subsequent testing revealed that there were no significant differences between the regression slopes for verbal and performance IQ.

The beta weights for the regression slopes of the two measures of IQ associated with the three schizotypy factors (pathway b) are also listed in

Table 3. Increased scores for interpersonal and disorganized schizotypy were significantly associated with reduced performance IQ among both male and female participants. There were no such associations with verbal IQ or with cognitive-perceptual schizotypy. These results suggest that while performance IQ may be a candidate as a mediator, any mediation effect may be specific to interpersonal and disorganized features of schizotypy. Regarding pathway c′, the regression slopes relating malnutrition to schizotypy while accounting for the influence of the mediator indicated no significant direct pathways. Thus, the mediation effect was full. The results for pathway c, which accounts for the relationship between malnutrition and schizotypy without the influence of the mediator, revealed that with one exception, there were no significant effects.

Psychosocial adversity at age 3 was found to be related to both intelligence measures as well as to interpersonal and disorganized schizotypy (

Table 3). Consequently, while there was a mediation effect of performance IQ on the relationship between psychosocial adversity and schizotypy, a significant c′ pathway indicated that this effect was partial and that the relationship was present in the absence of the mediator variable. Since psychosocial adversity was present in the modeling of the relationships between malnutrition and schizotypy, it was taken into account as a potential confounding variable of those relationships.

Additional analyses of the data confirmed the results (

Table 4). Regression analyses were used to generate the modified Sobel index and bootstrap analyses, as described by Preacher and Hayes (

26). Bootstrap analyses provide results that are independent of the form of the distribution of the data and thus represent strong confirmation of the finding that performance IQ is a mediator of the relationship between malnutrition and schizotypy. The results were further confirmed by analyses using the structural models described by VanderWeele (

27) (see the online data supplement).

Discussion

The results of our study broadly support our hypotheses. IQ was established as a mediator of the malnutrition-schizotypy relationship. The mediation model supports the suggestion that poor nutrition early in childhood results in poorer cognitive performance in later childhood, which in turn is associated with the development of two factors of schizotypy in early adulthood. Importantly, performance but not verbal IQ at age 11 was found to mediate this relationship. This mediation effect was specific to the interpersonal and disorganized features of schizotypy and was not observed in cognitive-perceptual schizotypy (also see reference

28). These mediation effects applied to both male and female participants. Our findings remained robust when they were reanalyzed for both the effects of attrition in sample size and the effects of additional hypothesized moderating variables.

To provide a hypothesis for future brain imaging studies, our findings suggest that malnutrition may predispose individuals to hippocampal and frontal brain impairments, which in turn predisposes them to schizotypy. There is evidence that the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex are dysfunctional in schizophrenia (

29), although the role of the prefrontal cortex in schizotypy is more controversial (

12). One study using rats demonstrated that excitability of the prefrontal cortex is lowered by early postnatal malnutrition, and this prefrontal deficit persisted even when adequate feeding was later introduced (

30). Neuronal and synaptic loss in the hippocampus has also been found to result from postnatal protein deprivation (

31). Prenatal dietary deprivation affects subregions of the hippocampus (

32), while prenatal protein malnutrition alters the response of medial prefrontal neurons to stress (

33). The only study of the effect of malnutrition on discrete brain areas in humans reported that frontal and prefrontal lobe volumes were lower in children who were malnourished in early life (

34). Taken together, these prenatal and postnatal studies provide initial evidence that those areas of the brain that are dysfunctional in individuals with schizophrenia and schizotypy personality disorder are regions that are also affected by malnutrition.

Another question is with regard to the extent to which particular brain areas are related to measures of intelligence. One MRI study demonstrated a positive relationship between IQ and gray matter density in both the orbitofrontal cortex and the cingulate gyrus (

35), while another study reported a positive relationship between IQ (mainly performance IQ) and temporal gray matter, temporal white matter, and frontal white matter volumes (

36). These findings support some linkage between low IQ and frontal dysfunction (

8). Also consistent with the finding of performance IQ as a mediator of the malnutrition-schizotypy relationship are meta-analytic and later empirical findings demonstrating that early performance IQ is more predictive than verbal IQ of later schizophrenia (

37,

38).

Mediation effects were found for interpersonal and disorganized features of schizotypy but not for cognitive-perceptual features. These findings are consistent with a model of schizotypal personality in which interpersonal and disorganized (but not cognitive perceptual) features are hypothesized to be elements of a form of schizotypy (neuroschizotypy) that is neurodevelopmentally based, with its antecedent in early prenatal and early postnatal factors. Poor early nutrition was specifically hypothesized to be one contributing factor to this form of schizotypy (

12). No significant relationship was observed between cognitive-perceptual schizotypy and IQ, a finding that was also observed recently by other investigators (

28). The heightened self-awareness of thought processes reflected in cognitive-perceptual schizotypy (

Table 1) may partly account for this null effect and may partly explain why few, if any, studies have reported IQ deficits in cognitive-perceptual schizotypy (

12).

Our finding of a linkage between early malnutrition and adult schizotypy as demonstrated through reduced performance ability is broadly consistent with a growing body of evidence linking nutritional status to risks for schizophrenia spectrum disorders as well as to prevention of cognitive breakdown. Using this same sample, we previously demonstrated that an experimental environmental enrichment intervention from ages 3 to 5 years consisting of better nutrition, more physical exercise, and cognitive stimulation resulted in a significant reduction in schizotypy at age 23 in participants who had poor nutritional status prior to the beginning of the intervention (

39). The fact that there was a significant interaction between nutritional status and the experimental enrichment intervention suggests that nutrition was a key component in this better outcome. Because the children in the enrichment program received portions of fish that were 2.5 times greater per week than the portions received by comparison subjects, increased levels of omega-3 fatty acids in their diet may have contributed to the beneficial effect. Recent evidence for the efficacy of omega-3 in preventing cognitive breakdown in schizophrenia can be found in a randomized controlled trial (

40). Our findings, combined with those of prior studies demonstrating that poorer prenatal nutrition is associated with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, contribute to growing empirical evidence suggesting that nutritional factors may be taken into account in future risk and prevention studies of schizotypal personality disorder.

Several limitations to our study need to be recognized. First, while the observed associations are consistent with a causal model, the findings cannot establish causality. Second, the findings cannot be generalized from individual differences in schizotypal personality in the community to schizotypal personality disorder in a clinical population, although the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire measure was validated against a clinically defined schizotypal personality disorder sample. Third, further studies are required to assess the generalizability of these findings from Mauritius to other regions. Fourth, we caution that postnatal malnutrition may also reflect prenatal malnutrition, and consequently we cannot argue for any temporal specificity to the postnatal period. Fifth, the measure of psychosocial adversity was based on data collected in the initial study phase and thus could not reflect more recent approaches, which might include family assets, although such a variable was included in the later analysis, which is presented in the online data supplement. Sixth, the main analyses were carried out in a sample consisting of some participants who were also involved in the intervention study (

39). However, analyses presented in the data supplement demonstrated that elimination of these participants did not change the results. Seventh, the position put forward is likely a simplification of a more complex reality. For example, there could be other potential processes that result in variations in IQ, which in turn is likely to be only one of a number of possible moderators of the malnutrition-schizotypy relationship. Null findings for some alternatives that we had the capacity to examine (birth complications, birth weight, temperament, and psychosocial adversity at ages 11 and 23) are presented in the data supplement. Finally, it is recognized that low IQ is an indirect proxy for brain dysfunction, and consequently we caution that these findings cannot directly identify specific brain mechanisms that mediate the malnutrition-schizotypy relationship.

Despite these limitations, our findings bring initial research on nutrition and schizophrenia spectrum disorders a step further. The prospective longitudinal design enabled us to identify the temporal ordering of variables, moving from malnutrition at age 3 to poor cognitive functioning at age 11 to schizotypy at age 23. In addition, findings in a sample of male participants were replicated in a sample of female participants, indicating the robustness of the malnutrition-schizotypy relationship. Furthermore, of the few prior studies of the relationship between nutrition and schizotypy, none appear to have assessed mediating factors. A unique contribution of our study is that it goes beyond establishing a longitudinal link between malnutrition and schizotypy and moves toward an understanding of the mechanism of action. Given that poor nutrition is an alterable risk factor, the future challenge raised by these findings concerns whether nutritional enhancements are capable of improving brain functioning and reducing some features of schizotypal personality disorder.