Cognitive theories of depression suggest that symptoms arise from mood-congruent emotion processing bias, whereby overly negative attention or interpretations tend to favor negative emotional stimuli (

1,

2). Previous imaging studies have demonstrated that the amygdala plays a key role in face-emotion processing (

3–

5). Several studies have reported that depression is associated with greater amygdala responses to negative (sad and fearful) emotions in faces (

6,

7). Furthermore, amygdala responses to negative face emotions have been reported to be attenuated by antidepressant treatment in individuals with depression (

8); however, it remains uncertain whether these changes are related to remission or to drug treatment (

9) and whether such changes apply to negative emotions in general or only to specific emotions. The amygdala is particularly sensitive to fearful faces, with greater responses to this emotion compared with responses to any other face emotion (

10). It is unclear from the literature whether the negative bias present in depression relates to enhanced amygdala responses to fear or to sadness (or both) or to attenuated responses to happy faces. In a study of depressed patients, Sheline et al. (

8) reported increased amygdala response to fearful (and happy) faces that decreased with antidepressant treatment. The finding of increased amygdala activation in depressed patients in response to fearful faces was replicated by the same group of investigators (

11,

12), but other studies have failed to replicate this finding (

13,

14). Most of the reports suggest that amygdala responses to sad faces are exaggerated in depression. In a recent article, Victor et al. (

9) used a combined cross-sectional and longitudinal design and found greater amygdala responses to subliminal, but not overtly presented, sad faces in currently depressed individuals relative to healthy comparison subjects, and the inverse was observed in response to happy faces. This is only in partial agreement with the findings of several previous studies that reported enhanced amygdala activation in response to both masked and unmasked sad faces (

7,

15–

21). Victor et al. also reported that antidepressant treatment reversed the abnormal amygdala responses, which is consistent with findings from previous functional MRI (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) pretreatment studies (

8,

15,

22–

32); however, the relevance of this finding to the mechanism of action of antidepressants is unclear, since the authors also reported exaggerated responses to sad faces in nonmedicated patients in remission. This may reflect biological differences in the targets of pharmacological action and clinical improvement. For example, Suslow et al. (

7) reported that currently depressed patients receiving antidepressant treatment had enhanced amygdala responses to sad faces and blunted responses to happy faces, and Fu et al. (

33) reported that increased amygdala responses to sad faces normalized in nonmedicated depressed patients after their symptoms improved following treatment with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). In the present study, we used an indirect face-emotion processing task in a combined cross-sectional and longitudinal design to test the hypotheses that negative bias in depression involves enhanced processing of both sad and fearful emotions and that antidepressants induce remission by correcting these biases. We predicted that currently depressed patients would show greater amygdala responses to both sad and fearful faces relative to healthy comparison subjects and to untreated patients in stable remission and that the responses would normalize only in those patients achieving remission while receiving antidepressant treatment.

Discussion

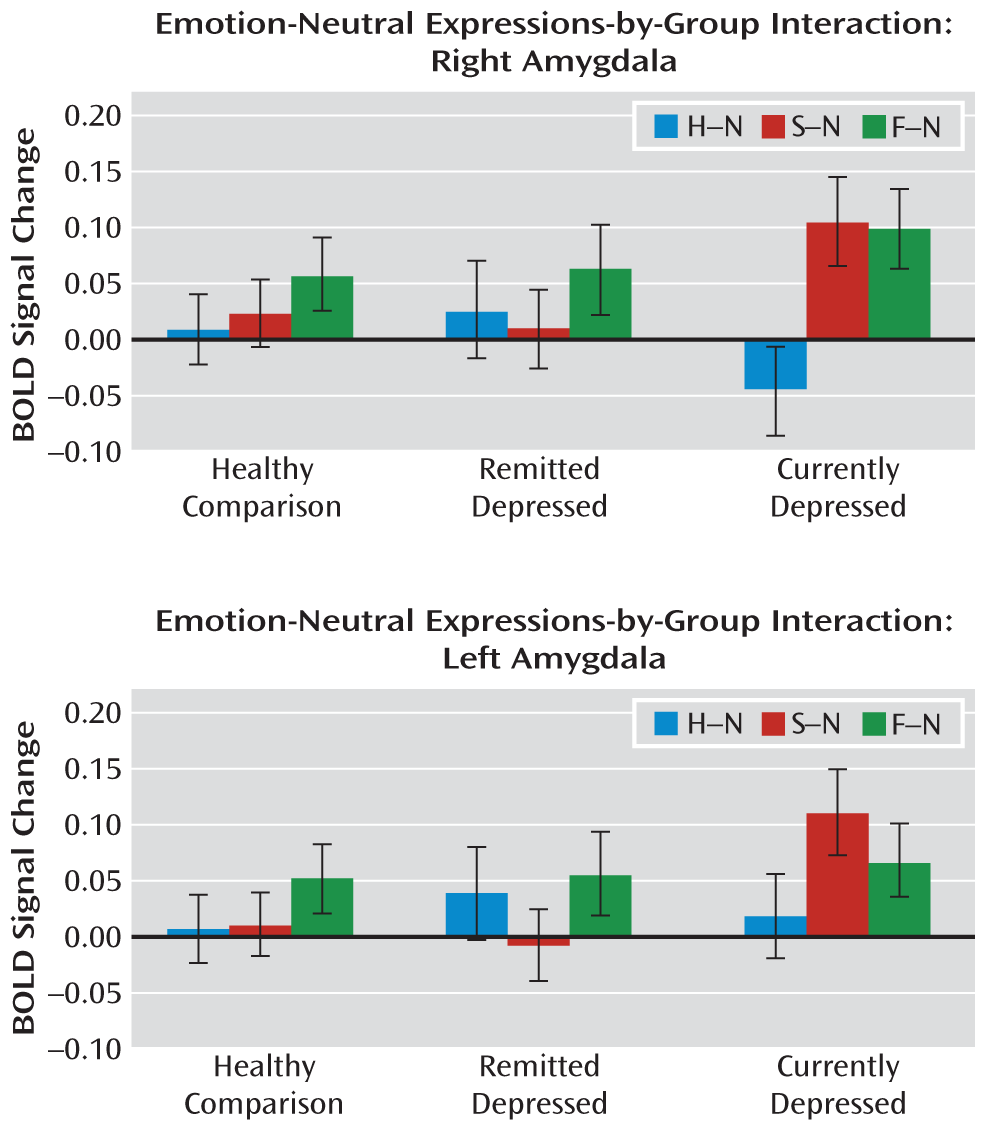

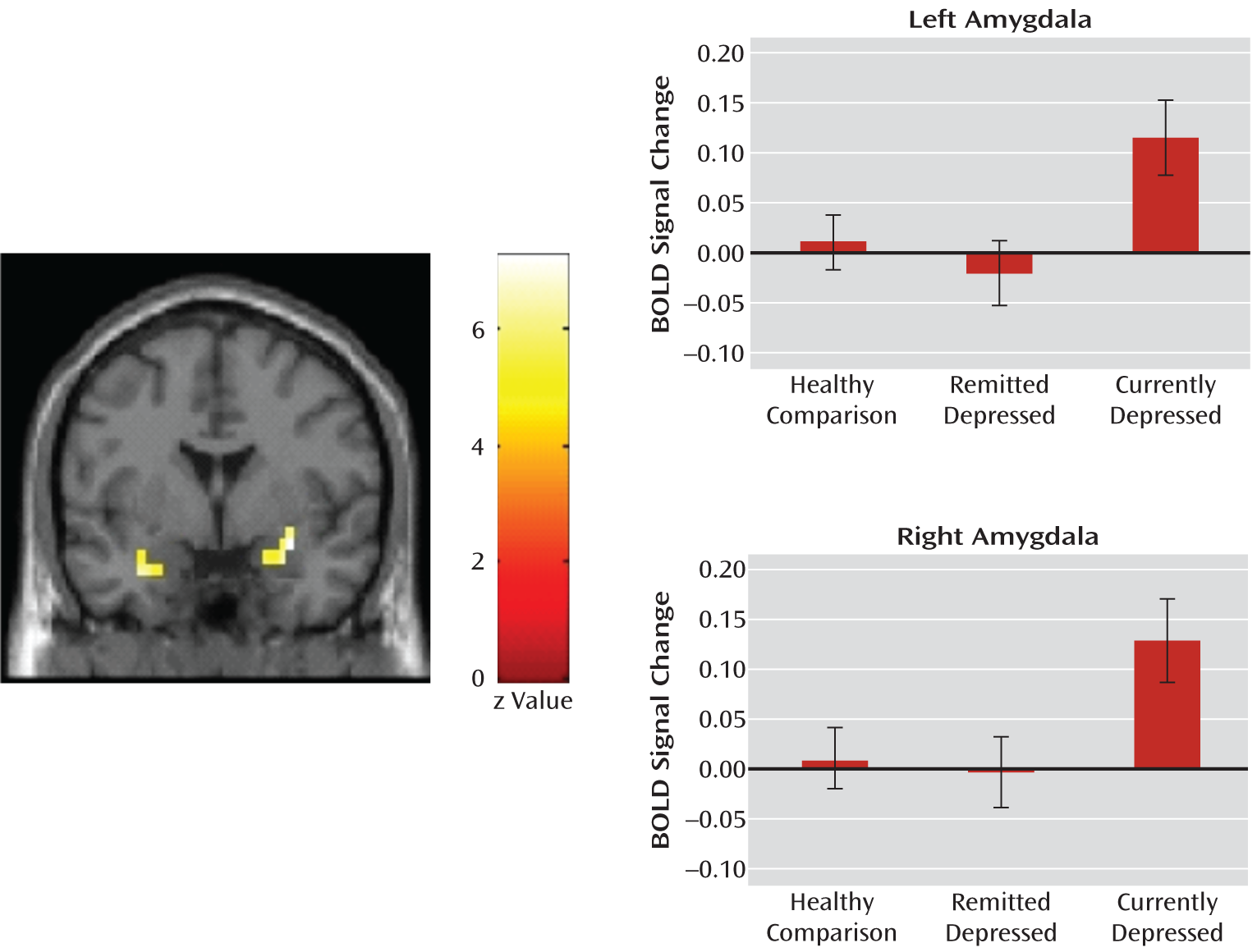

The main finding of our study was that significantly increased activity in the amygdala in response to sad but not fearful faces was observed in currently depressed patients, and this aberrant activation was normalized with successful antidepressant treatment. No group differences were observed in response to happy faces or in response to simply viewing the faces themselves. Nonmedicated depressed patients in remission did not differ from healthy comparison subjects in any of their responses.

This study is the first, to our knowledge, to report amygdala responses to both fearful and sad faces in the same group of patients relative to healthy comparison subjects. Contrary to our prediction, responses to fearful faces did not differentiate depressed patients from healthy comparison subjects in any of the comparisons. Our findings support a selective role of the amygdala in the processing of sad faces in depression and in relation to improvement of symptoms. Major depression presents with a variable intensity of anxiety and frequently with comorbid axis I anxiety disorders (

44); however, the contribution of anxiety symptoms to greater amygdala responses to fearful faces remains poorly investigated (

8,

11,

12). We excluded patients with any comorbid anxiety disorder, and thus it is possible that comorbid anxiety disorders may have contributed to previous findings of increased amygdala response to fearful faces in depressed patients (

6,

12). This is consistent with the findings of Fales et al. (

12), who reported that controlling for anxiety disorders abolished some of the effects seen in the amygdala in depressed patients in response to fearful faces. Similarly, increased activation in this region in response to fearful faces was related to trait anxiety in healthy comparison subjects in another study (

45) and to the severity of anxiety symptoms in a study of children with generalized anxiety disorder (

46).

Our findings suggest that the increased amygdala responses to sad faces were state anxiety-related in the currently depressed group, since this activation was abolished after short-term citalopram treatment and was not observed in nonmedicated patients in remission. This observation is consistent with findings from previous treatment studies (

8,

9,

15,

22–

32). However, in a study by Victor et al. (

9), nonmedicated depressed patients in remission were reported to have enhanced amygdala responses to masked sad faces that were similar to responses in nonmedicated patients for whom successful treatment had normalized the amygdala response. This contrasts with our findings and could be interpreted as a direct effect of antidepressant treatment masking a continuing abnormality that could confer vulnerability to depression. Consistent with this are results from studies of both acute (

47) and repeated (

48) administration of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in healthy volunteers that have demonstrated attenuated amygdala responses to fearful faces, indicating that there are direct effects of SSRIs on amygdala responses to emotional faces. However, this cannot explain our finding of similar amygdala responses between nonmedicated patients in remission and healthy comparison subjects, and we previously reported the same finding in a larger cohort of both medicated and nonmedicated depressed patients in remission, which included the patients reported in the present study (

49). However, there has been relatively little research of nonmedicated patients in remission. In a task using fearful faces, Norbury et al. (

50) observed no alteration in amygdala responses in nonmedicated patients in remission, similar to our findings. Additionally, Fu et al. (

33) reported that improvement in depression following CBT normalized pretreatment increased amygdala responses to sad faces. In contrast, in a study using PET imaging in combination with an indirect face-emotion processing task, Neumeister et al. (

51) observed increased metabolism in the amygdala in response to sad faces in major depressive disorder patients in remission. Thus, it is not currently possible to fully reconcile the contradictory findings in the literature, but one possible explanation could be the face-emotion paradigm used and that a subliminal presentation is better able to uncover abnormal amygdala sensitivity in individuals with remitted depression than an indirect task in which the emotion can be recognized.

We did not observe significant differences between groups in amygdala responses to happy faces in our cross-sectional analyses. Other studies have not demonstrated a consistent pattern of amygdala activation in response to happy faces in depressed individuals, with results ranging from no significant differences (

17,

52) to attenuated responses (

8). Some studies have reported increased amygdala responses following treatment (

9,

17), whereas we found no significant effect, and in fact the response appeared to be lower in our patients (

Figure 1). Thus, it is not clear what role, if any, altered amygdala response to happy faces plays in depression and response to treatment.

Given previous evidence for the attenuation in amygdala responses to fear following repeated SSRI treatment in healthy volunteers (

47,

48) and acute citalopram administration in comparison subjects and nonmedicated patients in remission (

53), we expected to find attenuated responses to this emotion in currently depressed patients treated with citalopram compared with nonmedicated depressed patients in remission. A number of possible explanations exist with regard to our finding of no differences between the two groups. These possible explanations are that 1) there exists a difference in amygdala modulation between patients with a history of depression and healthy volunteers as a result of chronic SSRI treatment in depressed patients; 2) there is a disappearance of the effect with a longer duration of treatment (8 weeks in the present study compared with 1–2 weeks in studies of healthy volunteers); or 3) the stage of remission (early versus established) modulates the effect. The one significant difference we observed between the groups was a decreased right amygdala response to happy faces in patients receiving the SSRI. While this may have been a chance finding, a genuine difference could reflect the difference in the duration of remission, or more speculatively, this could contribute to the poorly understood description by some patients of a damping down of emotions with SSRI treatment (

54).

Victor et al. (

9) reported group differences, similar to those reported in our study, in a task using masked emotional faces but not when emotional faces were presented without masking. The authors inferred that the emotional biases in amygdala responses in depressed individuals are automatic, below conscious awareness, and strengthened by masking. This reasoning is in line with our results and the findings of others (

15) of robust differences in amygdala response to sad faces in tasks using indirectly presented unmasked faces. The important factor may be that both masked and indirect unmasked tasks reduce conscious attention to the emotional information in faces, leaving automatic emotion processing to predominate. In keeping with this theory, a recent study of depression reported enhanced amygdala responses in depressed patients relative to comparison subjects only in response to unattended (but not attended) fearful faces (

12), although, as discussed above, the enhanced responses to this emotion may relate to an anxiety component rather than to depression itself.

Although given the literature, our study was focused a priori on the amygdala and its central role in emotion processing, it is important to recognize that the amygdala is part of a wider network involved in affective processing. The amygdala is not a unitary structure, and topographically lateral nuclei receive sensory inputs with projections to basolateral and central complexes involved in amygdala efferents and emotional memory (

4). Taking into account that our study did not have the spatial resolution to explore regional activation within the amygdala, it is of interest that we observed the greatest signal change in lateral areas, similar to those reported by Victor et al. (

9) and consistent with an abnormality at the early stages of information processing when sensory information is being integrated in emotion centers of the brain. Our whole-brain analysis demonstrates, similar to other studies (

9,

22), that the processing of sad facial expressions involves a network that includes the amygdala, hippocampus/parahippocampal gyrus, and insula, and it is known that the anatomical pathways between the amygdala and hippocampus play a role in encoding, retrieval, memory consolidation, and storage of emotional information (

55,

56). Additionally, decreased hippocampal volume has been consistently reported in depression (

57). While we did not find that depression severity correlated with amygdala activation in response to sad or fearful faces, our exploratory analysis did reveal significant correlations between anxiety and depression severity scores and BOLD signal change in the parahippocampal gyrus (see the online data supplement).

Strengths of this study include the large sample of currently depressed patients and depressed patients in remission, measures repeated in the same patients before and after treatment, and control for nonspecific repetition effects by testing healthy comparison subjects over the same interval. However, our study does have several limitations. Currently depressed patients experienced symptoms in the moderate range, and we did not include more severely ill patients who may have shown a different pattern of abnormality. We also cannot be certain that the same results would have been obtained using face-emotion tasks of a different design. Further studies including masked expressions of sadness and fear could help clarify the role of these emotions in relation to pharmacological treatment and clinical improvement. The implications of the findings with regard to vulnerability to depression and to the effect of treatment itself are uncertain without studies of relatives of depressed patients or studies of medicated and nonmedicated depressed patients in remission at the same distance in time from a depressive episode. We aimed to compare patients who achieved remission with those who did not, but our study had insufficient power to test this hypothesis. Inspection of the data did not suggest a difference between patients who achieved remission and those who improved. A larger sample of patients who did not remit with treatment is needed to separate the role of drug effects from the effects of remission on face-emotion processing. Finally, a placebo-treated group of depressed patients would allow changes as a result of remission itself to be identified without the confounding variable of drug treatment.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that abnormal amygdala responsivity to indirect processing of sad faces in depression appears specific to this particular emotion and that it is bilateral and appears to be a state, rather than trait, abnormality. Further work is needed to determine how specific this is to unipolar depression compared with other psychiatric disorders, such as bipolar depression. Our findings also raise a question about the validity of the use of fearful face-emotion processing with the parameters we used as a biomarker for antidepressant action in healthy volunteers, given that amygdala activation was not related to state or trait depression or altered by antidepressant treatment in our sample.