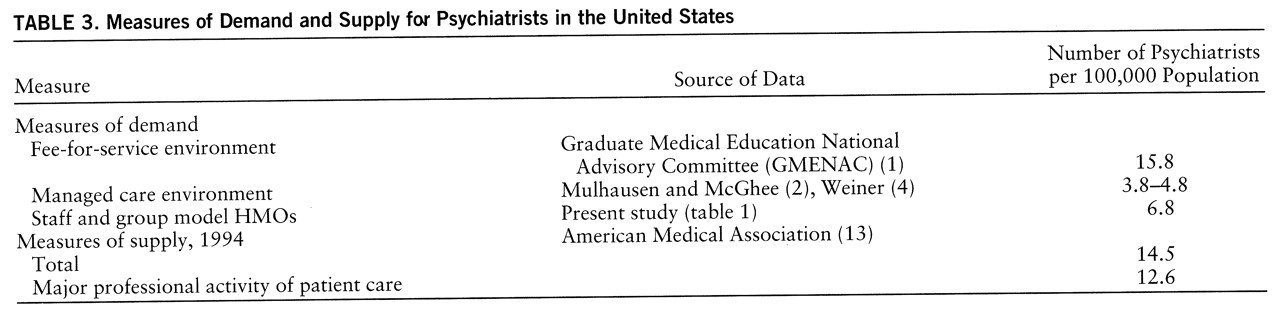

The physician need projections made in 1980 by the Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee (GMENAC) (

1) assumed a fee-for-service reimbursement environment, and the estimates generally are considerably higher than estimates of the number of physicians required in a managed care environment (

2–

4). The Association of American Medical Colleges, the Institute of Medicine, and the Pew Health Professions Commission say fewer physicians are needed to care for the population as managed care expands, and plans are being made to head off what some say could be a large physician surplus (

5–

8). This issue is especially relevant for psychiatrists. The GMENAC estimate of the need for psychiatrists in a fee-for-service environment was 15.8 full-time-equivalent psychiatrists per 100,000 population (

1), whereas managed care estimates have ranged from 3.8 to 4.8 per 100,000 (

2,

4).

RESULTS

Fifty of the 54 HMOs provided usable data on the number of full-time-equivalent primary care physicians, 30 provided usable data on the total number of full-time-equivalent psychiatrists on staff or under contract, and 26 provided full-time-equivalent data on nonphysician mental health providers.

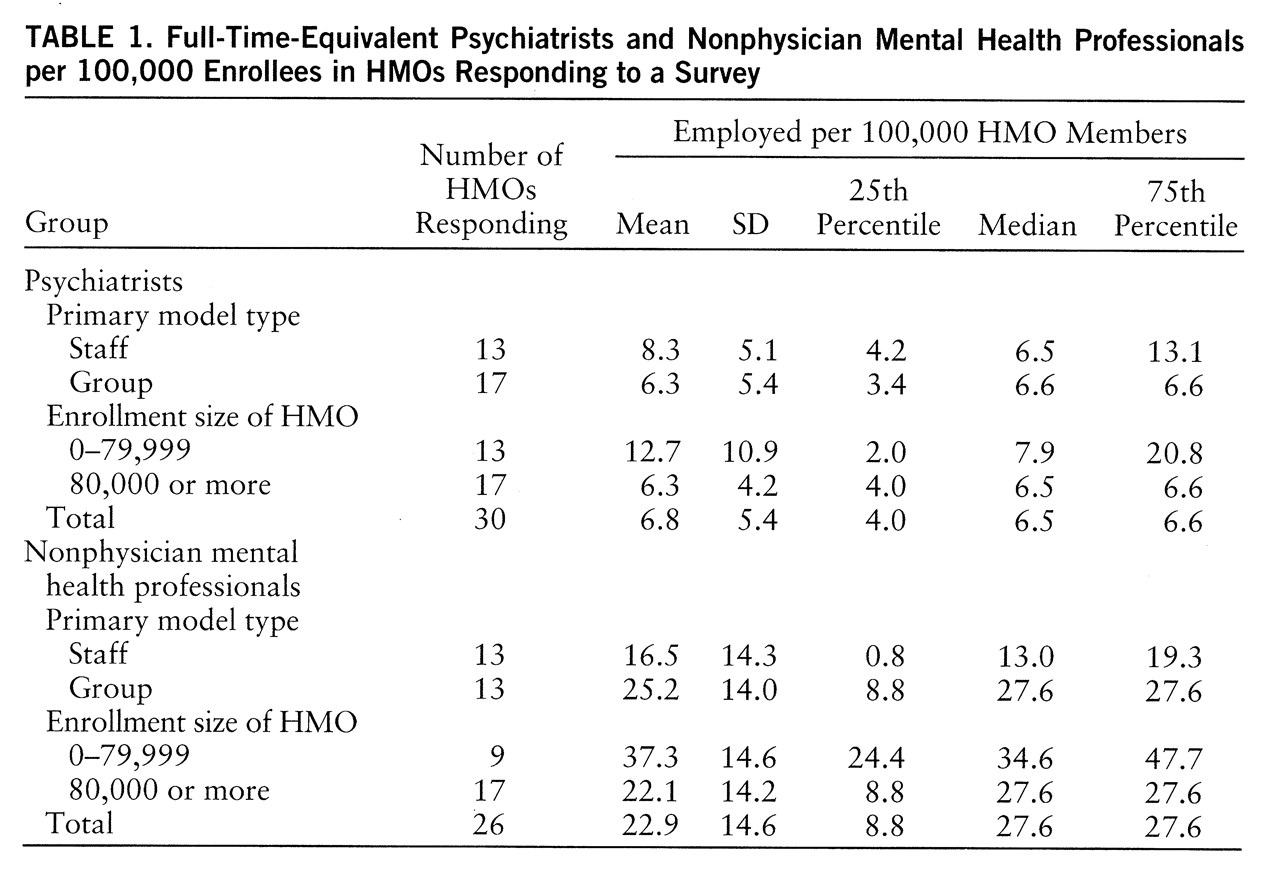

Table 1 presents total number of full-time-equivalent psychiatrists per 100,000 HMO members. The overall enrollment-weighted mean ratio was 6.8. The differences between small (fewer than 80,000 members) and large (80,000 or more members) and between staff and group model HMOs were not statistically significant at the p=0.05 level.

Table 1 also presents total number of full-time-equivalent nonphysician psychiatric professionals per 100,000 members. The overall enrollment-weighted ratio was 22.9. This ratio also failed to differ significantly between small and large HMOs, and between the staff and group models.

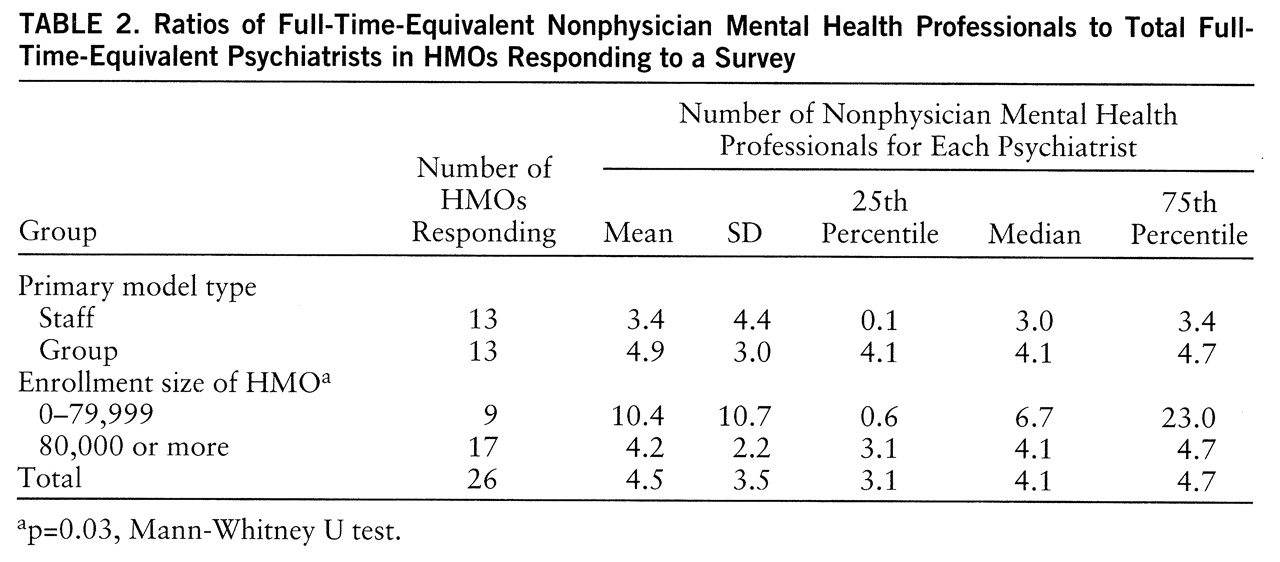

= The mean weighted ratio of nonphysician psychiatric professionals to psychiatrists was 4.5 to 1 (

table 2). The ratio in smaller HMOs was significantly higher than that in larger HMOs (Mann-Whitney U=36, p=0.03).

Table 3 compares the observed number of psychiatrists per 100,000 staff and group model HMO members to three estimates of psychiatrist-to-population requirements and to the actual number of psychiatrists per 100,000 in the United States in 1994. The number of psychiatrists per 100,000 HMO members is less than half the requirement estimated by GMENAC, which assumed a fee-for-service environment, and is substantially lower than the existing nationwide ratio of 12.6 patient care psychiatrists per 100,000 population (

13). It is, however, about 40% to 80% greater than the ratio that has been estimated by other studies under the assumption of a managed care environment (

2,

4).

DISCUSSION

To understand the implications of these data for health workforce policy, it is essential to consider them in a broader context. Psychiatric staffing levels in closed-panel HMOs do not provide the full picture and, taken alone, are not a satisfactory basis for projecting the demand for psychiatrists' services by the entire population.

Existing models to predict future needs for psychiatrists lead to contradictory estimates. Need-based approaches, which rely on estimates from epidemiologic studies, typically suggest that there is a severe shortage of psychiatrists, and especially child psychiatrists. Need-based models do not, however, take into account society's willingness to allocate resources to fill that need.

Demand-based approaches, in principle, are more likely to accurately estimate the number of psychiatrists the society will support. Lacking valid methods to directly measure demand, such approaches typically have used existing utilization patterns to estimate it. A related approach to estimating need, which has been called “benchmarking,” relies on the ratio of psychiatrists to population in certain geographic areas or market sectors (

14). Although this method has its limits, it permits some informative comparisons to be made. For example, the overall psychiatrist-to-population ratio is higher in the United States than anywhere else in the world, even in countries that have full-service national health insurance with comprehensive coverage for psychiatric illnesses.

To analyze the future demand for psychiatrists, it is useful to divide the mental health care market into four sectors, each with its own demand dynamics:

1. The out-of-pocket sector. This sector's size is unknown, but it probably is large. It includes upper-income people who choose to pay directly for care and those who are without insurance and outside the public system. The demand for psychiatrists in this market segment is related to the number of highly educated people with high levels of discretionary income. Other sources of demand in this sector are those unemployed, between jobs, or without employer coverage for mental health care, those whose health insurance does not cover desired services, and those who choose not to use their insurance coverage for mental health services, sometimes because of concern about confidentiality (

15). It is difficult to say whether this sector is growing, and even more difficult to estimate the number of psychiatrists it can support. The number of U.S. households with annual income over $75,000 (in constant 1993 dollars) increased from about 9.4 million to about 12.1 million between 1985 and 1993 (

16). On the other hand, out-of-pocket payments have been shrinking steadily as a percentage of all health care expenditures for more than 30 years (

17). The uninsured have increased in number since the 1980s (

18), but they frequently forgo needed care because they cannot afford it (

19).

2. The public sector. This was the other major component of the market for psychiatric services before the 1960s, existing initially in state hospitals and later expanding into public community settings. The demand generated by this sector is a function of the apportionment of public funds to mental health care and specifically to psychiatric services. The level of funding in the public sector varies considerably from state to state, and may not coincide with the amount and degree of psychiatric morbidity presenting to public settings.

3. The indemnity insurance sector. From the 1960s into the 1980s the growth of indemnity health insurance, including Medicare, Medicaid, and employer-sponsored coverage, expanded the demand for the services of psychiatrists and other mental health professionals. The overall size of the indemnity sector has decreased rapidly in recent years as the fourth sector, managed care, has grown. Moreover, utilization review and precertification requirements have increased to the point that completely “unmanaged” indemnity coverage has all but disappeared, at least from private health insurance. Managed care is now beginning to make inroads into Medicare and Medicaid as well.

4. The managed care sector. In this sector, allocation of resources to purchase psychiatric services is subject to organizational, financial, and procedural efforts to make the delivery of mental health care more efficient. The data presented here provide a picture of mental health staffing in one part of the managed care sector. There are many unanswered questions about the number of physicians needed in HMOs and other kinds of health plans. Estimates based on this sector do not include the use of out-of-plan providers. Nevertheless, the consensus of observers is that psychiatrist-to-population ratios (like other specialist-to-population ratios) are lower in a managed care environment than in a fee-for-service system.

Other developments, such as pharmacological advances and the changing responsibilities of primary care providers, may affect psychiatrists' efficiency and roles. The ways in which managed care organizations use nonphysician mental health professionals may be another critical factor to consider when projecting future requirements for psychiatric services. The findings presented here are congruent with previous studies that cite the important role of nonphysician mental health professionals in the managed care sector. In this study, the mean ratio of nonphysician psychiatric professionals to psychiatrists was 4.5.

Future psychiatrist-to-population ratios may approach those seen today in staff and group model HMOs, or they may be somewhere between these levels and those estimated by GMENAC in a fee-for-service environment. It seems unlikely, however, that future demand for psychiatric services will be as high, relative to the size of the population, as it was before the managed care revolution. On the other hand, if there are almost seven full-time-equivalent psychiatrists in HMO networks for every 100,000 members, it also seems unlikely that the total demand for psychiatrists will be as low as four or five per 100,000. Given the uncertainty about the demand side, it is critical that the dynamics of the supply side be understood.

The challenges to psychiatry are great. The enormous changes in the health care system, and the effects of those changes on the role of psychiatrists in the treatment of mental and addictive disorders (

10,

11), may be fueling U.S. medical graduates' declining interest in psychiatry (

20), despite the generally good employment opportunities for psychiatrists (

21,

22). For several years psychiatry has relied heavily on international medical graduates to fill U.S. residency slots (

23). Narrow definitions of the role of psychiatry and calls to restrict the access of international medical graduates to U.S. residency slots may have unintended consequences, given the uncertainties of estimates of the demand and need for psychiatrists. Efforts need to be undertaken to better estimate how changes in the residency pool affect the steady state of the overall supply of psychiatrists. Without adequate projections of the influence of supply side changes, the number of psychiatric residents may fall too quickly, for the wrong reasons, and too far. If adjustments are made on the basis of the lowest estimates of demand in a managed care environment, the resulting numbers may undershoot the mark by a wide margin.