Age at Onset Through Life Table Analysis and Duration of Illness

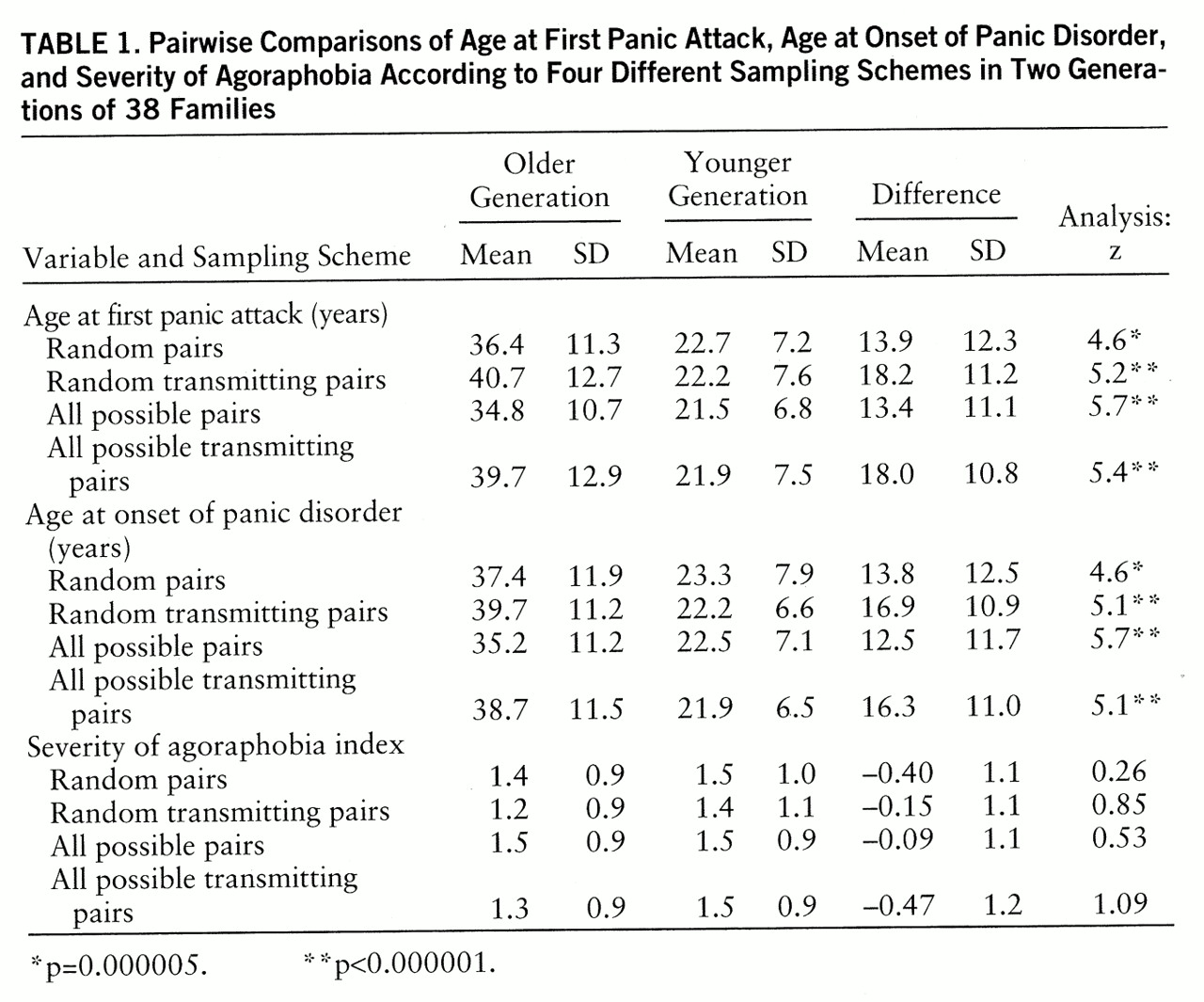

There was a marked difference in age at onset of panic disorder between members of the older and younger generations. The survival analysis showed a significantly earlier onset of panic disorder for members of the younger generation (Gehan-Wilcoxon test value=3.5, p=0.0002) (

figure 1).

The median duration of illness was 17 years for the subjects in the older generation and 5 years for the subjects in the younger generation, a significant difference (Kruskal-Wallis H=27.5, df=1, p<0.0001). In the older generation, 53.8% of the 52 affected subjects had received at least one medical treatment for panic disorder, and in the younger generation, 56.4% of the 62 affected subjects (χ2=0.08, df=1, n.s.).

Pairwise Comparisons

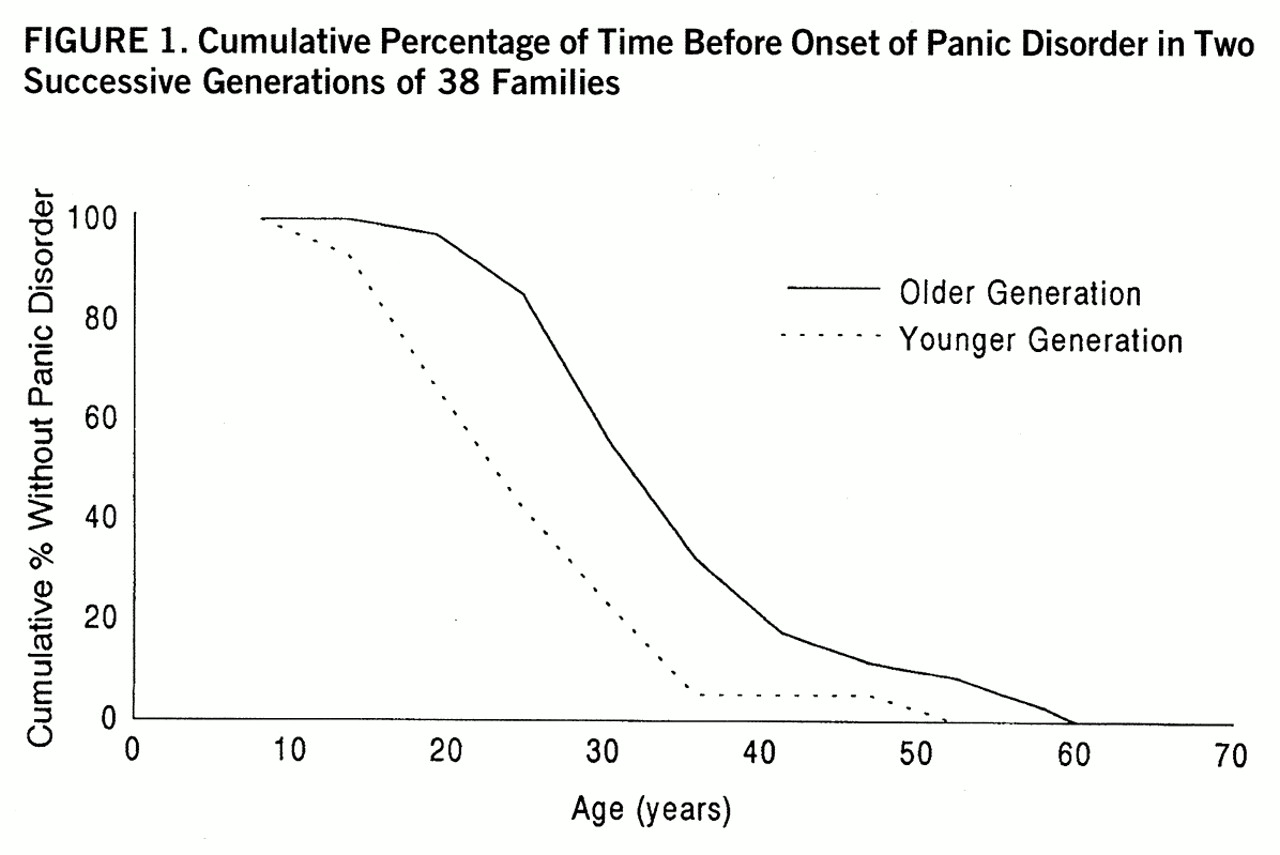

In all pairwise comparisons, significantly earlier age at onset for members of the younger generation was consistently found (

table 1). Anticipation of age at onset of panic disorder and of age at first panic attack, respectively, were observed in 88.2% and 90.7% of all possible pairs, 86.1% and 86.8% of random pairs, 94.9% and 95.1% of all possible transmitting pairs, and 94.4% and 92.1% of random transmitting pairs. When analyses were repeated after the exclusion of subjects with sporadic panic attacks, all differences remained significant. On the contrary, we found no significantly different severity of agoraphobia between the older generation and the younger generation (

table 1).

We also looked for hints of imprinting (parental-origin influence on differential expression of genetic material). When offspring in all of the transmitting pairs were divided into two subgroups, one with affected fathers (N=12) and the other with affected mothers (N=27), no significant difference in the anticipation effect was found (Mann-Whitney U=140.5, p=0.50).

Corrections for Possible Biases

Indications of how one can appropriately address possible identified sources of bias have recently become available (

16,

20,

23–

30). A bias might derive from the diminished life expectancy of severely affected individuals in the older generation, who would be more likely to die young and less likely to be interviewed. On the basis of family histories from multiple informants, we found that four dead members of the older generation were likely to have had panic disorder. They were assigned an onset age of 23 years, corresponding to the mean age at onset for members of the younger generation. All differences in anticipation of age at onset remained significant (p=0.00002).

Members of the younger generation may have an apparent paucity of late-onset cases because they are younger at the time of observation; this would exclude a proband's siblings who may become ill at a later stage. To address this issue (

16), unaffected members of the younger generation were assigned an onset age of 57 years, i.e., the mean current age of the members of the older generation. Even after this very conservative correction, age at onset remained significantly earlier in the younger generation than in the older generation (p=0.0007).

A recently recognized source of bias in anticipation studies is the differential age at interview of parent and child (

29); however, a new method to control for this has recently been found (

30). Briefly, the younger-generation subject's expected age at interview is compared with the observed age at interview (as the average of all the ages at onset in the older generation that are below the subject's age at interview), and then a paired t test is used to find out whether the difference is significantly higher than 0. After the application of this correction, anticipation remained significant: the observed mean age at onset in the younger generation for all pairs of relatives was 22.5 years (SD=7.3), and the expected mean age at onset was 24.6 years (SD=4.2) (t=3.20, df=54, p<0.002).

As first suggested by Penrose (

2), pairs consisting of a parent with early age at onset and a child with late age at onset would be unlikely to be ascertained because of the time span separating the two onset events (

23). Early-onset parents (defined as those with an age at onset ≤27 years, i.e., who are at least 2 years younger than the mean age at onset in the group of 551 outpatients with panic disorder) were present in 18% of the families. Among their offspring, 57% were already affected with panic disorder at the time of the study, and 70% of these had an earlier onset than that of their affected parent, with anticipation ranging between 1 and 11 years. Therefore, this bias should not have exerted a strong effect on this specific study group, even though only a lifetime follow-up of the offspring can definitely rule out such a possibility.

Another possible source of bias is the age cohort effect, or the tendency for an illness to show progressively earlier age at onset in successive birth cohorts. This has consistently been described for mood disorders in persons born after 1945 (

31,

32). A large U.S. community survey (

32), however, showed impressive stability of age at onset for panic disorder across different cohorts, which would therefore suggest the absence of an age cohort effect for this illness. One way to estimate control for the presence of a cohort effect on the difference in age at onset within parent-offspring pairs is to calculate the correlation between the difference in birth years and the difference in ages at onset within transmitting pairs (

20); we found this to be nonsignificant in all possible transmitting pairs (r=–0.14, N=39).

In mental disorders there may be an effect on the onset of an illness of the experience of being reared by an affected parent. To control for this we computed how many subjects in the younger generation had had their onset of illness before that of the older-generation parent. This proportion accounted for 21% of all possible transmitting pairs, a relatively high percentage if one takes into account the natural tendency of panic disorder to have its onset early in life.

Finally, the question of the so-called regression to the mean—i.e., the presence of a simple linear dependence in which the degree of anticipation gradually abates with the decreasing parental age at onset—was addressed. One way to re-propose the issue of regression to the mean (

33) as applied to anticipation is to plot the difference between age at onset for parents and offspring (x–y) against the age at onset for parents (x) and see how they are related. Some authors think that the presence of regression to the mean in the form of a linear relationship between anticipation and parental age at onset strongly argues against a real phenomenon of anticipation; in one study (

34) the hypothesis of “true” anticipation in schizophrenia was rejected because the authors observed a simple linear relationship between anticipation and age at onset in the parents, with a line of best fit very close to the one expected under the assumption that age at onset in offspring was normally distributed around the mean. Hodge and Wickramaratne (

28) have shown that anticipation and correlation of ages at onset between parents and offspring are two independent phenomena, and that regression analysis does not contribute to discriminating “true” anticipation from an effect due to ascertainment bias. It has also been argued by other authors (

4,

25) that regression to the mean does not exclude “true” anticipation, and McInnis et al. (

24) showed how for a set of randomly generated values of x and y, the correlation between x and x–y is significantly high, and the x intercept where x–y=0 coincides with the mean for the values of x. In our study group the regression coefficient of anticipation correlation between x and x–y is as high as 0.69 (F=34.07, df=1,37, p=0.000001), but the x intercept is at 26.2, well below the mean of parental age at onset (36.3 years) and thus in contradiction with the expectancy of Galtonian regression to the mean (

33).

The study was designed to minimize possible biases related to clinical severity as a primary cause for ascertainment (subjects with associated features of alcohol/substance abuse, which perhaps indicates greater severity and earlier onset, were excluded from the study, and index probands in the younger generation were excluded from analyses), possible biases related to additive genetic effects from both parental lines on the younger generation (all families with evidence of bilineality were excluded from the study), and possible biases related to preferential ascertainment of late-onset parents due to possible diminished fertility of early-onset patients (childless members of the older generation were included in the sampling schemes).