Follow-up studies have documented that attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) continues into adulthood in 10% to 60% of affected children and that its persistence is associated with high rates of psychopathology, social dysfunction, academic difficulties, and occupational failure (

1,

2). Although controlled studies have shown that methylphenidate (

3) and desipramine (

4) are effective in the treatment of ADHD in children and adults, methylphenidate is potentially abusable and short acting, and desipramine is associated with a wide range of adverse effects. This situation supports the search for safe and effective alternative agents.

Tomoxetine is an experimental compound, dissimilar in structure to other available antidepressants in that it is a highly selective noradrenergic reuptake inhibitor with little affinity for other neurotransmitter systems (muscarinic, cholinergic, histaminic, serotonergic, or α

1 or α

2 adrenergic) (

5). It has little effect on cardiac conduction, repolarization, and function. Because of its noradrenergic activity, its limited spectrum of adverse effects, and the absence of abuse potential, tomoxetine may be of benefit in the treatment of ADHD.

In this paper we report results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study of tomoxetine in the treatment of adults with childhood-onset and persistent ADHD. Because of its noradrenergic profile, we hypothesized that tomoxetine would be superior to placebo in the treatment of these patients.

METHOD

Subjects were 22 outpatients with ADHD who were between 19 and 60 years of age. Exclusion criteria consisted of clinically significant chronic medical conditions, abnormal baseline laboratory values, mental retardation (IQ less than 75), organic brain disorders, clinically unstable active psychiatric conditions, drug or alcohol abuse within the last 6 months, current use of psychotropics, and, for women, pregnancy or nursing. This study was approved by our institutional review board, and all subjects provided written informed consent.

All patients underwent a comprehensive clinical assessment. To be given a diagnosis of adult ADHD, subjects had to have 1) met full DSM-III-R criteria for ADHD by the age of 7 as well as currently, 2) described a chronic course of ADHD symptoms, and 3) endorsed impairment associated with the disorder.

To assess change during treatment, we used the following individual scales to examine ADHD, depression, and anxiety symptoms. The ADHD Rating Scale (

6) assesses each of the 14 individual criterion symptoms of ADHD in DSM-III-R on a severity grid (0=not present, 3=severe, overall minimum score=0, maximum score=42). The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory assess depression, and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale assesses anxiety. In addition, patients underwent a neuropsychological battery that included an auditory Continuous Performance Test, Stroop tests, the computerized Wisconsin Card Sorting test, and the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure. We administered the Hamilton depression scale, Hamilton anxiety scale, Beck inventory, and the neuropsychological battery before and after each arm of the study. The ADHD Rating Scale was administered weekly. The study design included two 3-week treatment periods separated by 1 week of washout. Study medication was titrated up to 40 mg/day by week 1 and 80 mg/day (40 mg b.i.d.) by week 2 and maintained at 80 mg/day by week 3 unless adverse effects emerged.

Improvement was defined as a reduction in ADHD Rating Scale score of 30% or more. To compare paired data between two time points, the McNemar test was used for correlated proportions. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used for nonparametric testing and the t test was used for parametric testing of continuous data. Since our design required repeated measures of subjects, we also conducted analyses using random effects, cross-sectional time series models, and the method of generalized estimating equations described by Diggle, Liang, and Zeger (

7–

9). We specified a first-order autoregressive working correlation matrix. This approach has several advantages over traditional methods such as repeated measures analysis of variance or multivariate analysis of variance. Most important, unlike traditional methods, these models need not exclude subjects with missing data. We tested for group differences in continuous variables using a random effects model that estimated main effects of drug (tomoxetine versus placebo), time (week in study), and order (tomoxetine first versus placebo first) as well as any interactions.

RESULTS

Of the 22 patients enrolled in the study, one was dropped because of emergent anxiety and irritability during the second week of tomoxetine treatment. Thus, the final study group consisted of 11 women and 10 men; their ages ranged from 20 to 59 years (mean=34, SD=9).

Thirteen patients had at least one lifetime comorbid psychiatric disorder, but only two had current ratings of depression or anxiety that were severe. Twenty patients had a family history of ADHD. Despite average to above-average intelligence, nine of the patients required tutoring in school and six had repeated at least one grade.

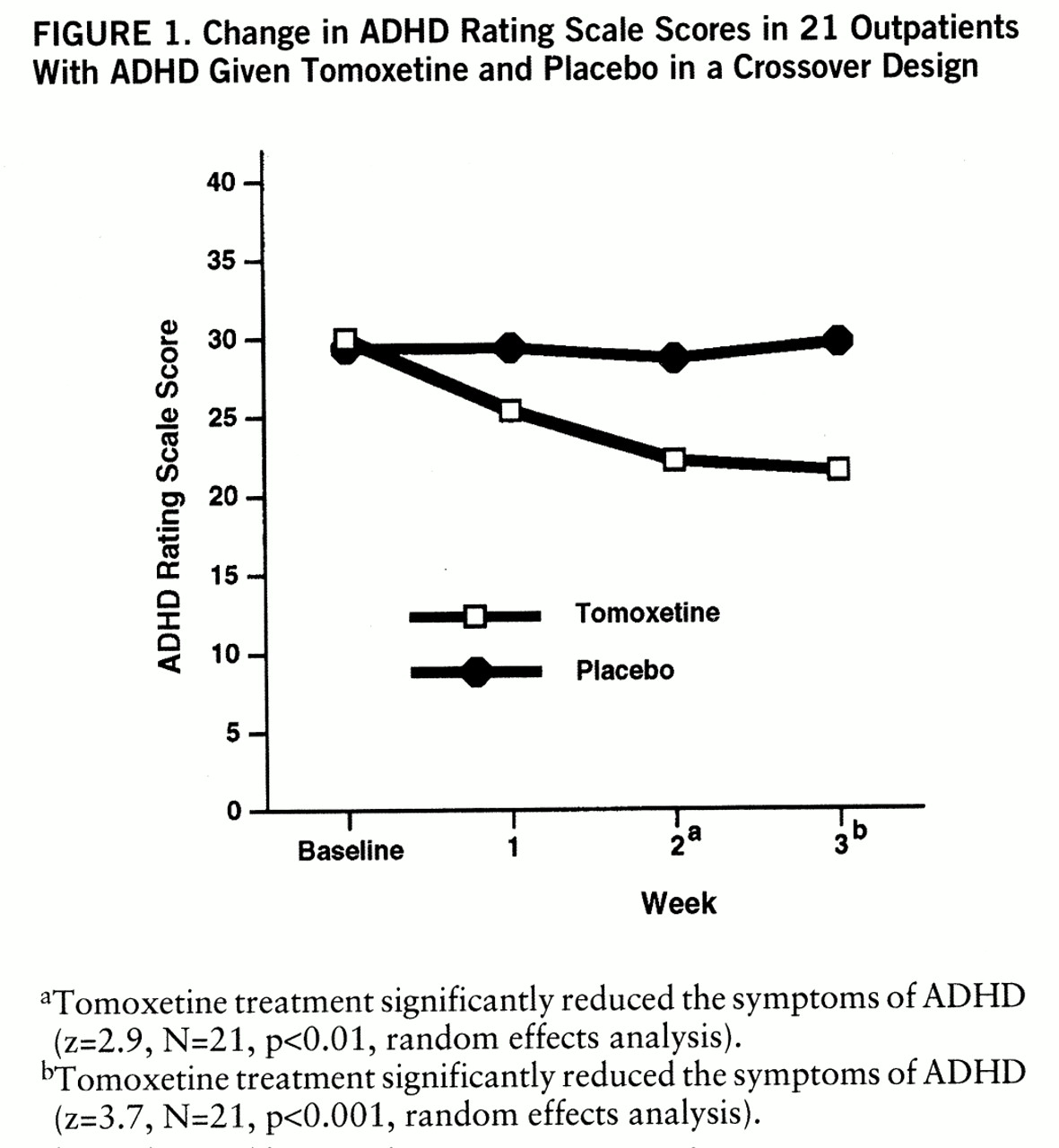

The average doses of tomoxetine and placebo at week 3 were 76 mg/day and 78 mg/day, respectively. Endpoint analyses revealed that tomoxetine significantly reduced the symptoms of ADHD (mean score on the ADHD Rating Scale at baseline=30, SD=6.7, versus mean score after 3 weeks of tomoxetine treatment=21.5, SD=10.1) (t=3.96, df=20, p=0.001, paired t test). In contrast, placebo did not (mean score on the ADHD Rating Scale at baseline=29.4, SD=6.3, versus mean score after 3 weeks of placebo administration=29.7, SD=8.8) (t=0.25, df=20, n.s.). Random effects analyses revealed that response to tomoxetine attained statistical significance by the second week of treatment and that there was further improvement by week 3 (

figure 1). There was a very significant drug-by-time interaction for ADHD symptoms (z=3.8, N=21, p<0.001) but no significant main effects of drug (tomoxetine or placebo) or time (baseline and weeks 1, 2, and 3). An order effects analysis failed to reveal a significant order effect (tomoxetine first versus placebo first) (z=1.6, N=21, n.s.) or significant interactions between order and week (z=0.6, N=21, n.s.) or between order and drug (z=1.9, N=21, n.s.).

The superiority of tomoxetine over placebo in improving ADHD symptoms was robust enough to be detectable in a parallel-groups comparison that used data restricted to the first 3 weeks of the protocol (z=3.2, N=21, p<0.01).

Using a preestablished definition of improvement of 30% or greater reduction in symptoms, we found that 11 of 21 patients showed improvement in ADHD symptoms while receiving tomoxetine, compared with only two who improved while receiving placebo (χ2=7.4, df=1, p<0.01, McNemar test). Tomoxetine, but not placebo, was associated with clinically and statistically significant improvement in individual ADHD symptoms. The most notable effects were observed on symptoms of inattention. We found no meaningful associations between improvement of ADHD symptoms and gender, socioeconomic status, or positive family history of psychiatric disorder. However, there was a trend toward greater rates of improvement in ADHD patients who had no comorbid disorders. Examination of the effects of tomoxetine on measures of depression and anxiety failed to reveal meaningful change over time on these measures.

Paired nonparametric analyses (Wilcoxon signed-ranks) revealed statistically significant beneficial effects of tomoxetine over placebo in the Stroop Color Word test (mean=52.1, SD=11, versus mean=48.6, SD=13) (z=2.6, N=21, p<0.05) and Interference T test scores (mean=53.9, SD=9, versus mean=50.7, SD=10) (z=2, N=21, p<0.05); there was no evidence of cognitive deterioration on any Stroop test.

Tomoxetine was well tolerated, and there were no serious adverse effects, except for the patient who became very anxious while receiving tomoxetine and was dropped from the study. One other patient developed anxiety and three patients developed insomnia while receiving 80 mg/day of tomoxetine, and one patient developed both anxiety and insomnia while receiving 80 mg/day of placebo. Appetite suppression occurred significantly more often in patients while receiving tomoxetine than while receiving placebo (χ2=5, p<0.05, McNemar test), but insomnia did not (χ2=1, n.s., McNemar test). However, there was no difference between mean endpoint weights between the placebo condition (mean=85.5 kg, SD=25) and the active drug condition (mean=85.2 kg, SD=26) (t=0.85, df=16, n.s., paired t test). In addition, although there were no statistically significant differences in standing or supine blood pressure between the active drug and placebo conditions, tomoxetine treatment was associated with increases in both standing (95 versus 84 bpm) (t=3.1, df=17, p<0.01, paired t test) and supine (77 versus 72 bpm) (t=2.7, df=17, p<0.05, paired t test) mean heart rates. Changes in heart rate ranged from –12 to 42 bpm, but the highest heart rate recorded was 126 bpm. ECGs also revealed heart rate elevation while patients were receiving tomoxetine (76 versus 72 bpm, N=18) (t=2.56, df=17, p<0.05, paired t test); however, there was no evidence of delayed conduction or repolarization associated with tomoxetine treatment.

DISCUSSION

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial of 22 adults with ADHD, treatment with tomoxetine at an average oral dose of 76 mg/day was well tolerated and effective. Although this was a crossover design, reduction in ADHD symptoms was robust enough to be detectable in a parallel-groups comparison during the first 3 weeks of the protocol (z=3.2, N=21, p<0.01). These results confirm the study hypothesis and suggest that tomoxetine may be useful for the treatment of ADHD.

The magnitude of response to tomoxetine treatment (11 [52%] of 21 patients) approximates the average improvement rate reported in previous studies of methylphenidate in adult ADHD (54%); it is somewhat lower than the response rate observed in our previous, methodologically similar trials of methylphenidate (

3) and desipramine (

4). Although this result suggests that tomoxetine could have a weaker effect in ADHD than other compounds, it is noteworthy that a similarly modest response rate of 58% was observed on our previously controlled trial of desipramine by the end of week 2. This could suggest that the 3 weeks of tomoxetine treatment in the present study may have been insufficient time for the clinical effect of tomoxetine to fully unfold.

Although a large portion of our study group had comorbid psychiatric disorders, the absence of meaningful associations between tomoxetine treatment and psychiatric comorbidity suggests that response to tomox~etine was specific to ADHD. In addition, improvement in Stroop Color Word and Interference T scores suggest that tomoxetine treatment may improve inhibitory capacity.

Although our use of a crossover design and the relatively short exposure to medication may have not been ideal, the results were robust enough to be detectable in a parallel-groups comparison. Nevertheless, these findings should be confirmed in a larger study with a parallel design.

Despite limitations, this study has shown that tomoxetine clinically and statistically significantly improved ADHD symptoms and was well tolerated. Although preliminary, these promising initial results provide support for further studies of tomoxetine in the treatment of ADHD.