Why schizophrenic patients smoke at high rates remains elusive

(6–

8). There are three main possibilities. First, the illness itself may lead patients to smoke. Possibly, patients with schizophrenia self-medicate with nicotine to alleviate both positive and negative symptoms as well as to improve cognition

(6). These putative beneficial effects of nicotine may be mediated through the regulation of a dysfunctional mesolimbic dopamine system

(9). It has been reported that there is a worsening of psychotic symptoms on stopping smoking and subsequent nicotine withdrawal

(10,

11). Second, smoking may be an etiological risk factor in schizophrenia. It may be that repeated activation by nicotine of the mesolimbic system over a lengthy period of time precipitates the onset of schizophrenia in vulnerable individuals. Third, genetic or environmental factors might predispose individuals both to develop schizophrenia and to start smoking. Much work in the genetics of both schizophrenia

(12) and nicotine addiction

(13) has focused on dopamine receptors. Possible pathophysiological links between smoking and schizophrenia have been the subject of a recent review

(14).

RESULTS

The smoking questionnaire was returned by 135 (80%) of the 168 patients; 73 (54%) of the respondents were male and 62 (46%) were female. However, seven patients, all smokers, did not complete the questionnaire fully; therefore, numbers vary slightly in different categories.

Comparison With Smoking Habits in the General Population

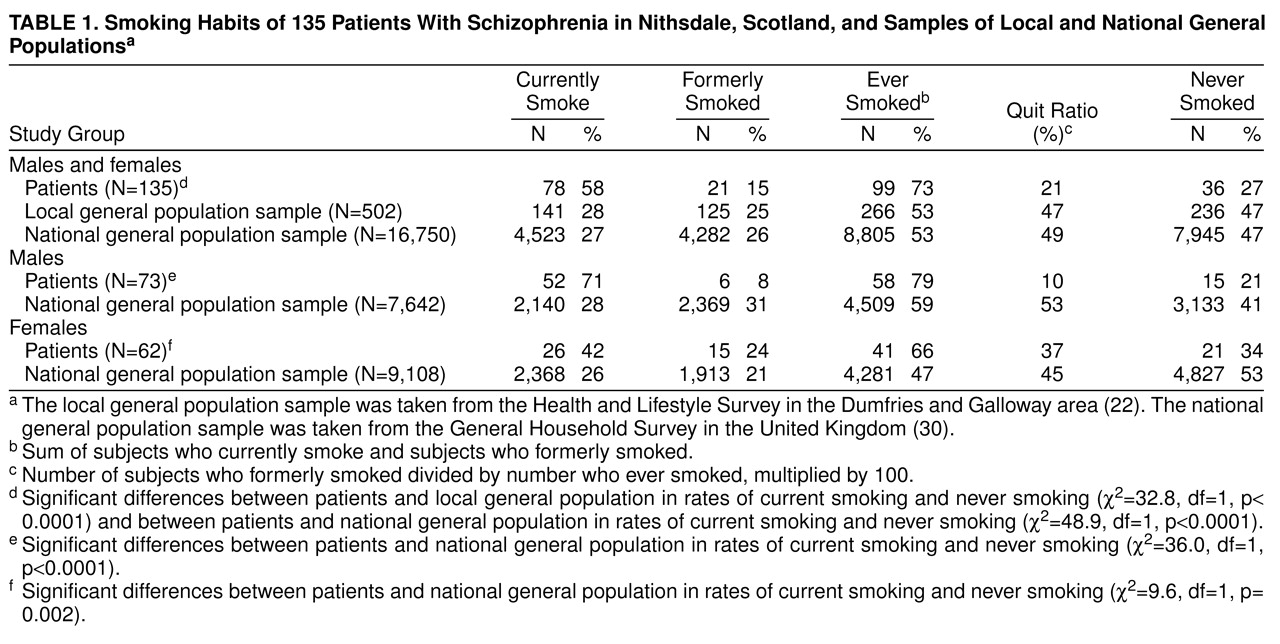

Table 1 shows the smoking habits of the 135 schizophrenic patients, a 1995 general population sample in the same area of South-West Scotland (Dumfries and Galloway)

(22), and a 1994 general population sample in the United Kingdom

(30). More patients than subjects in the two general population samples reported that they currently smoked, and more had smoked at some time in their lives. The quit ratio (the number who gave up smoking divided by the number who were currently smoking plus those who had given up smoking) was lower in patients.

Seventy-one percent of male and 42% of female patients were current smokers compared with 28% of males and 26% of females in the general population. The quit ratio among male patients was lower than that in the general population, but among female patients and females in the general population it was broadly similar (

table 1). Although there were similar numbers of male and female smokers in the general population, more male than female patients smoked (χ

2=11.8, df=1, p=0.001). More female than male patients had given up smoking (χ

2=6.5, df=1, p=0.01). The mean age at starting smoking was 17 years (SD=5) in patients and normal subjects

(22); there were no between-sex differences.

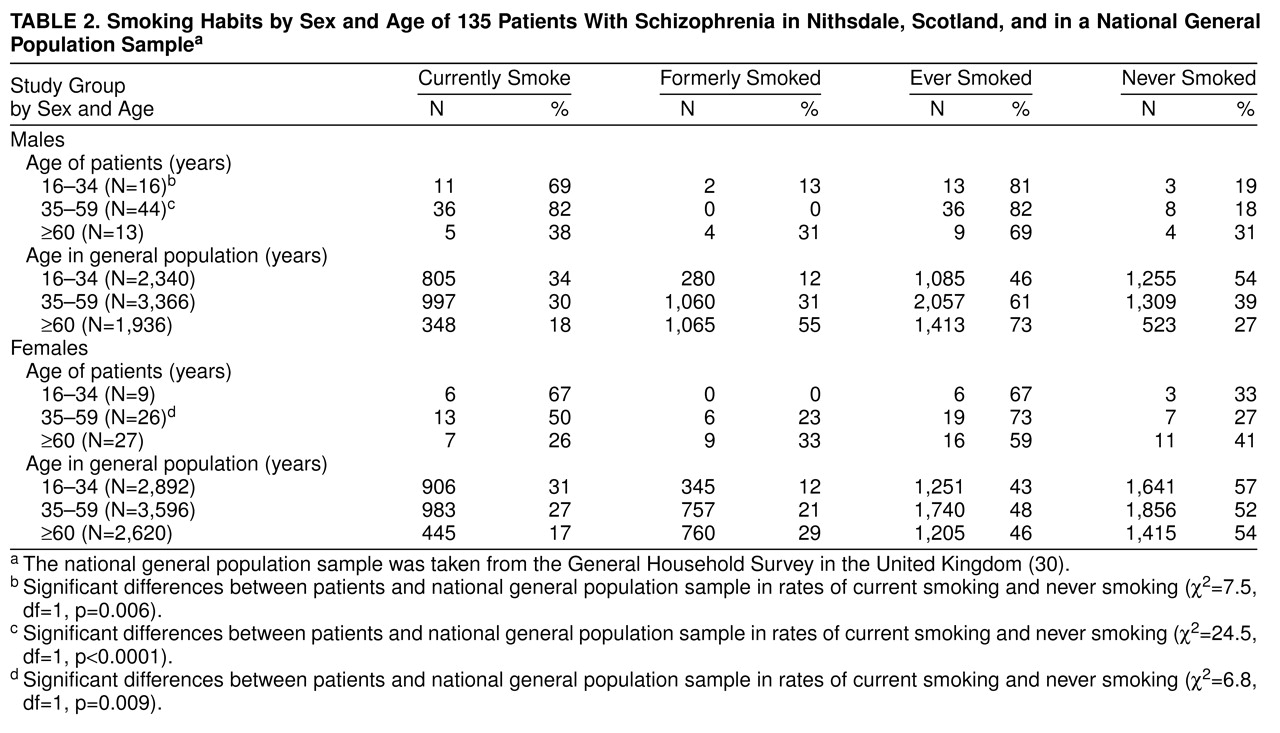

Table 2 shows the smoking habits by age and sex for patients and for the U.K. general population sample. Within each of the three age bands and for both sexes more patients than normal subjects were current smokers. These differences achieved statistical significance in males aged 16–34 and 35–59 and in females aged 35–59.

More patients who smoked were classed as heavy smokers; 53 (68%) of the patients who smoked were smoking 25 or more cigarettes daily (37 [71%] of male and 16 [63%] of female smokers), compared with 11% of the smokers in the local general population

(21) (χ

2=15.6, df=1, p< 0.0001).

Twenty-six (33%) of the patients who smoked reported that they wanted to give up smoking (22 [42%] of male and four [15%] of female smokers), compared with 60% of smokers in the local general population

(22).

Smoking Among the Schizophrenic Patients

Sixty-three percent [N=15] of inpatients, 62% [N=21] of day patients, 65% [N=26] of outpatients, and and 25% [N=9] of community-nurse-supported patients and patients only in contact with their general practitioner were smokers (χ2=8.4, df=3, p=0.04).

Seventy (90%) of the patients had started to smoke before the onset of their schizophrenic illness; the mean age at starting smoking preceded the mean age at onset of illness by 11 years (SD=10). There was a positive correlation between age at starting smoking and age at onset of illness in all patients (r=0.29, df=69, p=0.04). This relationship remained significant for female patients (r=0.47, df=24, p=0.02) but not for male patients (r=0.08, df=47, p=0.58).

Smokers and Nonsmokers Among the Schizophrenic Patients

Among the schizophrenic patients, there were more males among the 78 smokers (N=52 [67%]) than among the 36 nonsmokers (N=15 [42%]) (χ2=11.8, df=1, p=0.001). Smokers were younger (mean age=45, SD=13) than nonsmokers (mean age=56, SD=18) (t=3.80, df=131, p<0.001). The age at onset of illness was lower in smokers (mean=27, SD=10; males mean=27, SD=9; females mean=28, SD=11) than in nonsmokers (mean 31=years, SD=13; males mean=30, SD=13; females mean=32, SD=13), but these differences were not statistically significant. Smokers had had more hospital admissions (mean=7.5, SD=7) than nonsmokers (mean=5, SD=5) (t=2.09, df=131, p=0.04). Both male (mean=7, SD=6) and female (mean=8.4, SD=8.6) smokers had had more admissions than male (mean=4.6, SD=3.4) and female (mean=5.5, SD=6.2) nonsmokers, but the difference was statistically significant only in males (t=2.17, df=70, p=0.03, versus t=1.48, df=59, p=0.13).

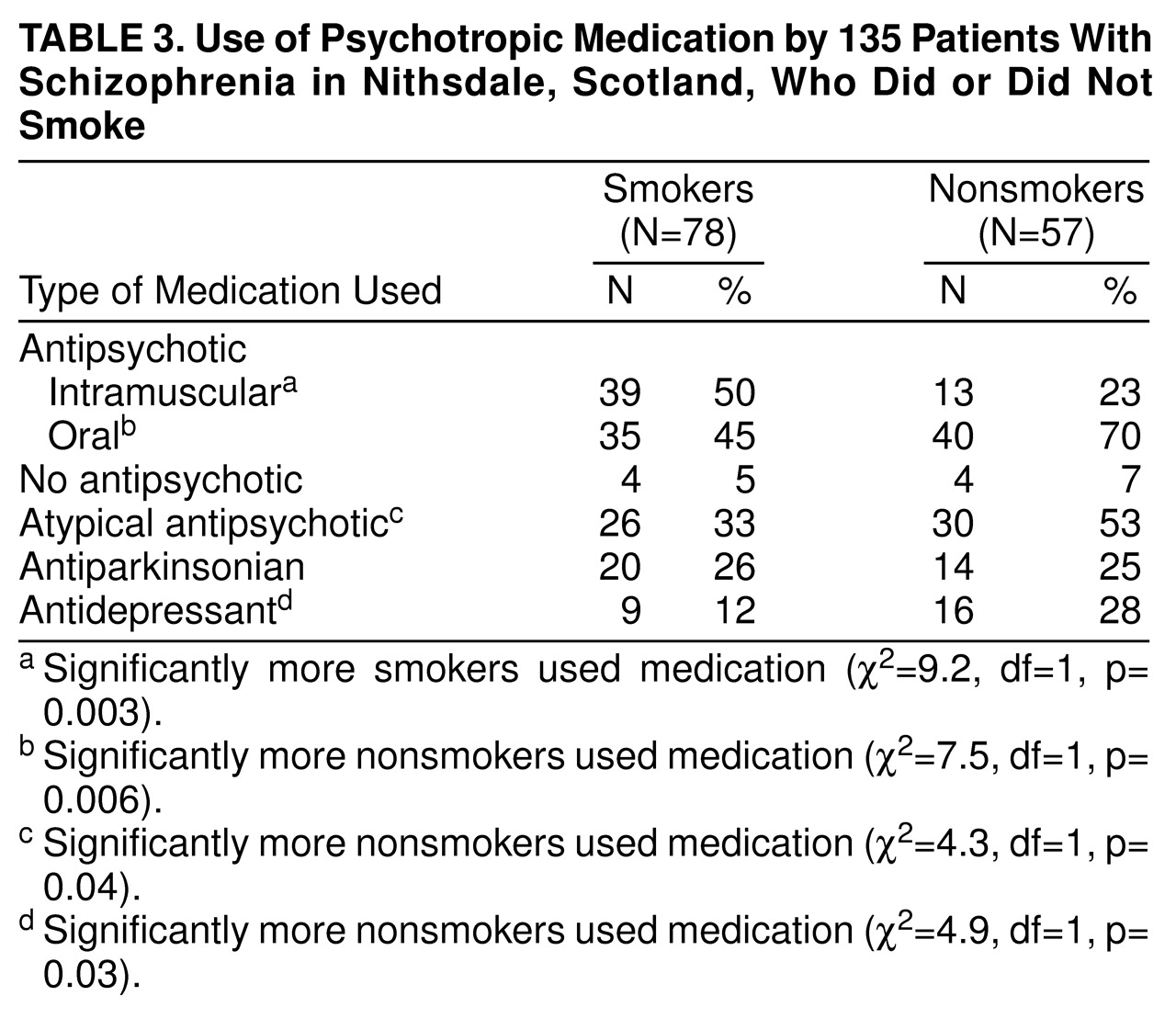

Table 3 shows the relationship between smoking and medication use among the schizophrenic patients. Smokers were significantly more likely to be receiving intramuscular antipsychotic medication and less likely to be receiving oral and atypical antipsychotics and antidepressants.

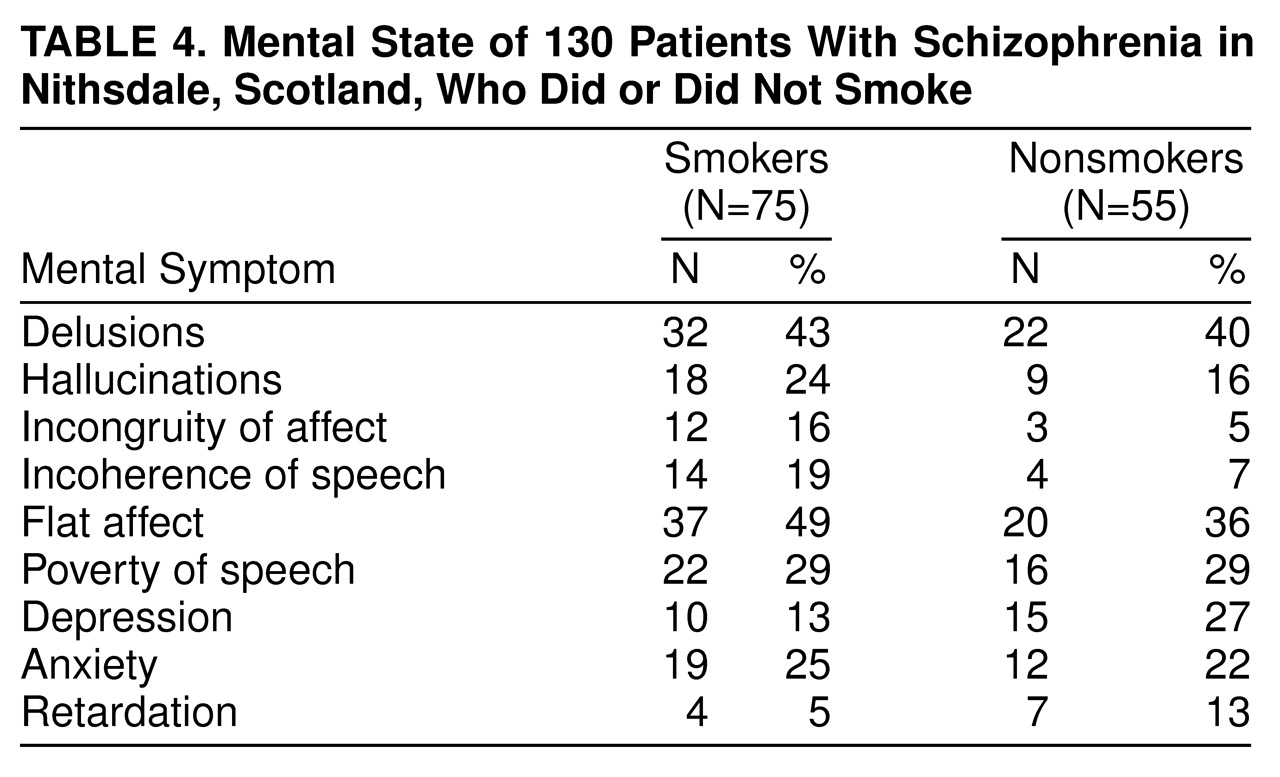

Table 4 shows the mental state findings for the smoking and nonsmoking schizophrenic patients. There were no significant between-group differences in the individual symptoms rated.

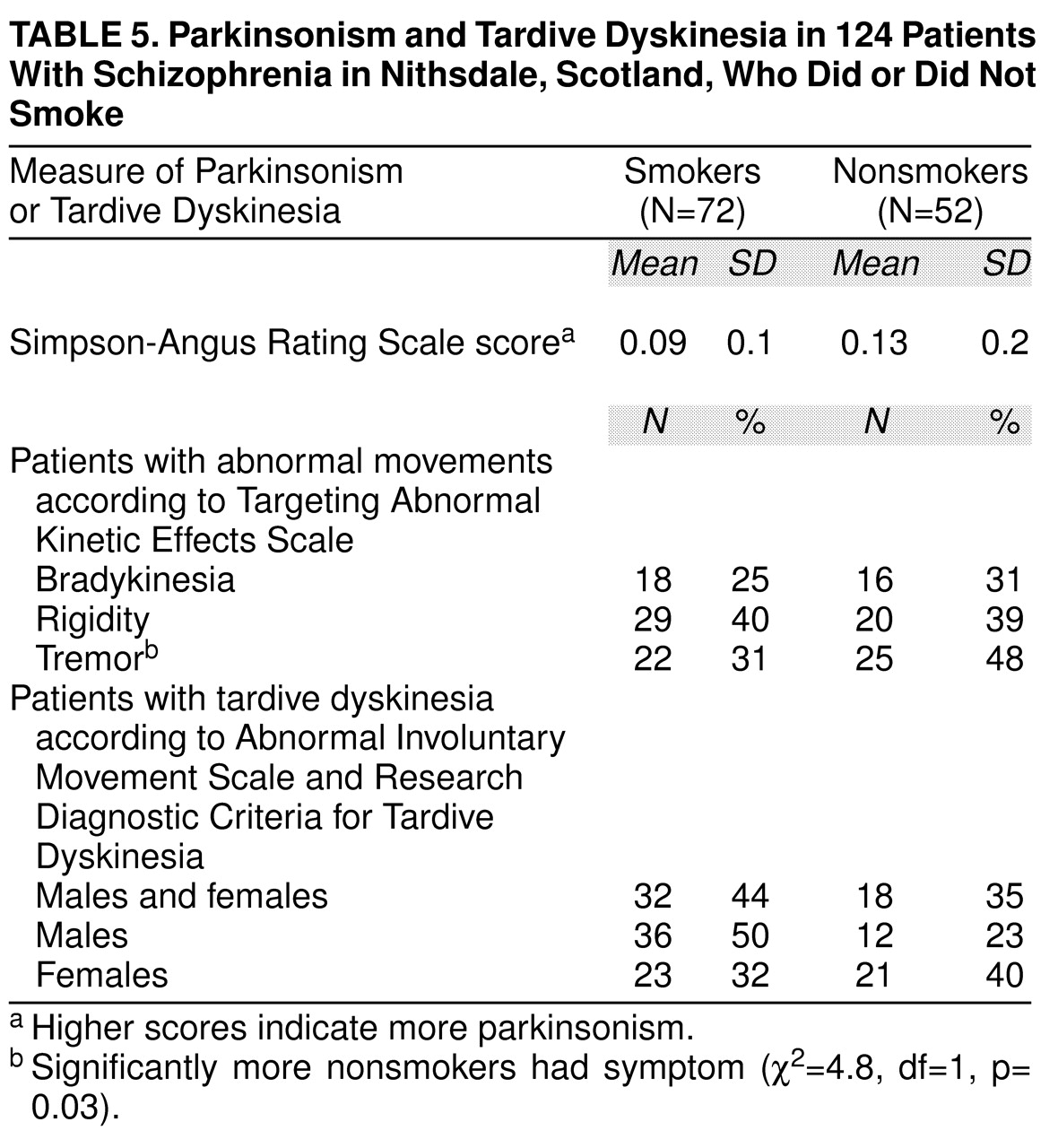

Table 5 shows the drug side effect profile for smoking and nonsmoking schizophrenic patients. Significantly more nonsmokers exhibited tremor. Twice as many male smokers had tardive dyskinesia than nonsmoking males, but the difference was not statistically significant.

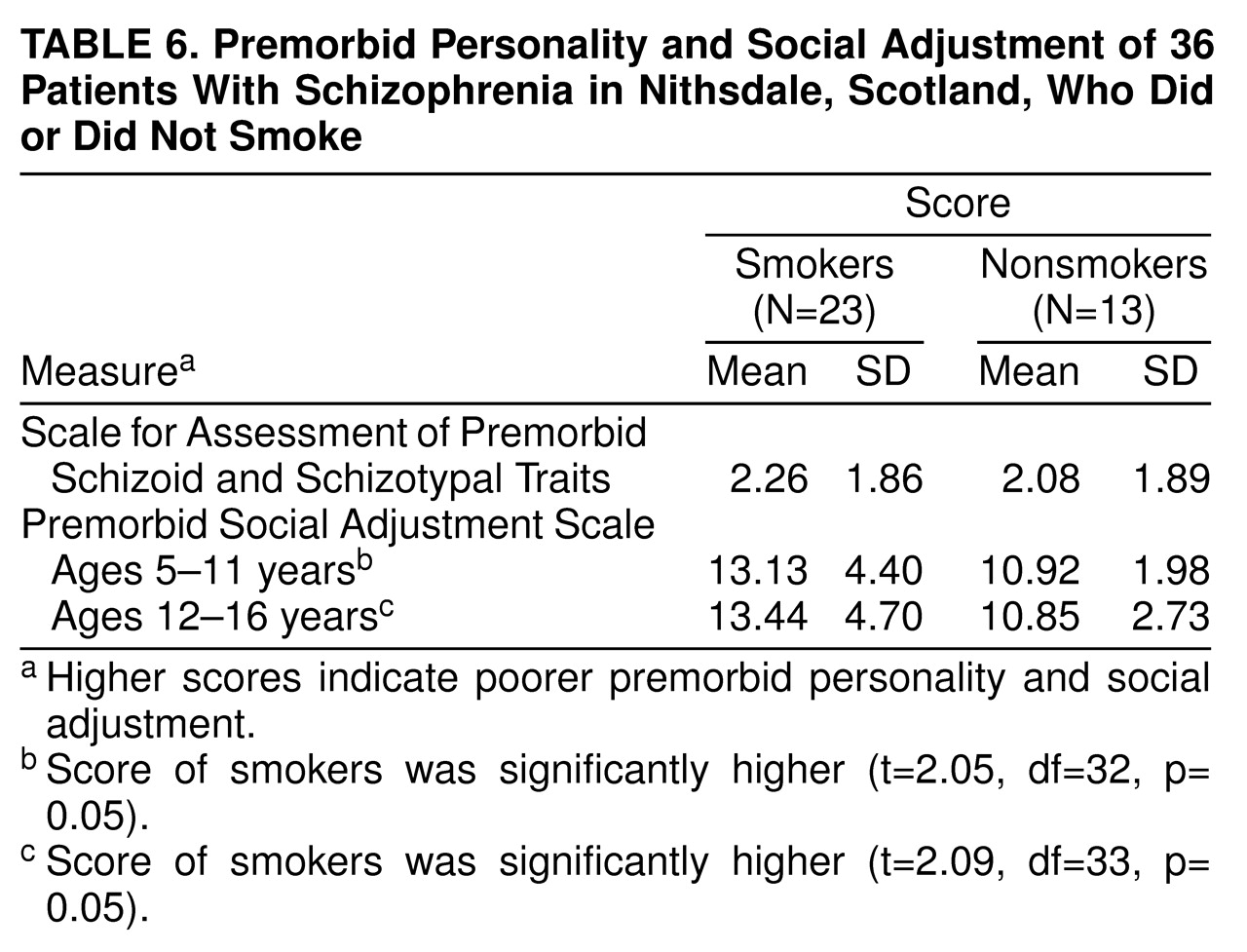

The mean scores on the Premorbid Social Adjustment Scale for ages 5–11 and for ages 12–16 and the mean scores on the Scale for Assessment of Premorbid Schizoid and Schizotypal Traits for smoking and nonsmoking schizophrenic patients are shown in

table 6. Smokers scored significantly higher than nonsmokers on the Premorbid Social Adjustment Scale for ages 5–11 and for ages 12–16, which indicates they had a poorer premorbid social adjustment at both ages 5–11 and ages 12–16.

DISCUSSION

We have found that the rate of cigarette smoking in schizophrenic patients from a discrete geographical area is more than twice that of a local population sample (58% versus 28%). The rate of 58% is lower than that found in other studies, but these studies looked at samples of patients who were more likely to be young and male

(1–

5), who have higher rates of smoking. To our knowledge, our study is the first to examine the smoking habits of patients with schizophrenia independent of selection bias. The differences between smoking rates in patients and in the general population narrow when we compare subjects who have smoked at some time in their lives (73% versus 53%). However, we found that many fewer schizophrenic patients than subjects in the general population are able to quit, especially among male patients (10% versus 53%).

Within the general population, there are groups where the smoking rate is high. For example, in 1991, the National Child Development Survey in the United Kingdom

(31) found that the rate of smoking in 33-year-old men who had no academic qualifications and lived in subsidized housing was 67%. This is a rate similar to that found in our young male patients, many of whom also had no academic qualifications and lived in subsidized housing. However, we believe our comparison with a general population sample is more valid because at the time our patients first started smoking (in their teenage years), they were distributed widely through a variety of educational and social backgrounds.

The rate of smoking in the general population sample, 28%, is similar to that found in other countries in the developed world. For example, in 1989, in six countries (Australia, Canada, Norway, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States) the rate in males ranged from 24% to 41%, and in females, 27% to 33%

(32). There is little information about the rates in developing countries.

Earlier in this article, we considered three possibilities to explain the association between high rates of smoking and schizophrenia. In the Nithsdale patients, it cannot be the symptoms of the illness itself or the effects of “institutionalization” that drove patients to smoke because 90% of the patients started smoking before the first episode of illness. However, patients who smoke were more poorly socially adjusted in their childhood than nonsmokers. Perhaps premorbid traits, rather than florid symptoms, lead schizophrenic individuals to smoke. Poor social adjustment in childhood is a feature of the neurodevelopmental form of schizophrenia

(33); other features include male sex, early age at onset of illness, and a more severe form of illness

(33). These features were found in our smoking patients, whose severity of illness was measured by contact with psychiatric services and numbers of admissions.

These results suggest that either premorbid characteristics typically found in neurodevelopmental schizophrenia lead to smoking or genetic and environmental factors lead both to neurodevelopmental schizophrenia and smoking. However, a third possibility is raised by our finding in women that the earlier the age at starting smoking, the earlier was the onset of schizophrenia. Might heavy nicotine consumption over a prolonged period of time, especially in vulnerable individuals, be another environmental risk factor in schizophrenia, through its action on the mesolimbic dopamine system?

The other principal difference between patients and the general population sample was that the level of addiction among patients was much higher: 68% of the smoking patients smoked 25 or more cigarettes per day, compared with 11% of general population smokers. There are several possible explanations for why patients smoke so much. Nicotine, like other drugs of addiction such as cocaine and amphetamine, activates the mesolimbic dopamine system

(34); this appears to be of critical importance for the reinforcing and reward properties of the drug

(35). However, patients were also receiving antipsychotic drugs, which produce marked dopamine receptor blockade. Possibly a very high level of smoking is necessary to overcome this blockade and produce the reward effects. It has been shown that, compared with baseline, patients with chronic schizophrenia smoke more after starting haloperidol

(36). It is also possible that schizophrenic patients smoke at high levels to self-medicate both positive and negative symptoms, although in our patients there was no difference between smokers and nonsmokers in the level of such symptoms. Because we believe that our smoking patients were drawn from a group that was more severely ill, however, we cannot rule out the possibility that nicotine is helping the patients’ mental states.

There were differences between smoking and nonsmoking patients in antipsychotic medication patterns. More smokers were receiving intramuscular antipsychotic medication and fewer were receiving oral and atypical antipsychotics. We find this hard to explain, but once again we could postulate that smoking is a marker for neurodevelopmental schizophrenia; schizophrenic patients who are more severely ill and more difficult to manage may be more likely to receive intramuscular drugs in the United Kingdom. More nonsmokers than smokers were receiving antidepressant medication. Nicotine’s positive effects on enhancing mood have been well described in the general population, and it may be that our smoking patients were successfully modifying their mood state with their heavy and regular consumption of nicotine.

Although more nonsmokers than smokers were receiving atypical antipsychotics, said to produce less extrapyramidal symptoms

(37), side effects were largely similar for both groups. Several studies have reported a lower rate of drug-induced extrapyramidal side effects in smokers

(2,

10,

38), others have reported no between-group differences

(3,

39,

40), but none has reported higher rates; this includes a study finding that smokers on average were receiving twice the dose of neuroleptics of nonsmokers

(2). Smoking increases neuroleptic metabolism by inducing hepatic microsomal enzymes

(41).

Although the difference between smokers and nonsmokers was not statistically significant, more male smokers (50%) had tardive dyskinesia. In three previous studies, two

(39,

40) found no relationship between smoking and tardive dyskinesia and one

(42) found tardive dyskinesia to be more common among smokers. A study of smoking in a population of normal men, few of whom had been exposed to neuroleptics

(43), found that 21% of men who smoked 20 or more cigarettes per day had dyskinesia. Cigarette smoke is rich in free radicals, which may cause structural damage to catecholaminergic neurons and, thus, tardive dyskinesia

(44).

It is clear from our study and previous work that heavy cigarette smoking and severe nicotine addiction are intimately associated with the schizophrenic illness. More patients with schizophrenia start to smoke, and few give up smoking. The patients’ high level of addiction almost certainly contributes to their reduced life expectancy

(45). Schizophrenic patients who smoke are an even more disadvantaged group within a very vulnerable population.