The 10 years from 1988 to 1998 brought significant changes in psychosocial and pharmacological treatments for anxiety disorders. For psychopharmacology, major innovations included the increased use of high-potency benzodiazepines such as alprazolam and clonazepam and the introduction and rapid acceptance of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

(1). These agents are now so commonly used that it is difficult to recall that 10 years ago, their use was much less common.

Changes in psychosocial prescriptions for anxiety disorders have been less dramatic and well publicized but are no less important. Most significant has been the growth of cognitive behavior therapy, an effective, highly operationalized, easily replicable form of psychotherapy. Originally regarded as a somewhat unorthodox treatment that was applicable only under limited circumstances, today cognitive behavior therapy is considered a psychosocial treatment of choice for panic disorder

(2) and is frequently recommended as the first-line therapy for other anxiety disorders

(3,

4). While advocates of psychodynamic therapy for anxiety disorders remain

(5), many believe that this form of treatment at present lacks empirical support, whereas supporting data for the use of cognitive behavior therapy are abundant

(2,

6).

The Harvard/Brown Anxiety Disorders Research Program began in 1988 to study the phenomenology, course, and treatment of DSM-III-R panic disorder with and without agoraphobia, agoraphobia without a history of panic disorder, social phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder. In previous articles, we have detailed various aspects of the treatments received by Harvard/Brown subjects for these disorders

(7–

9). In this article, we examine psychosocial treatments received by Harvard/Brown subjects between 1991 and 1995–1996 to determine whether changes in treatment have paralleled changes in recommendations for patients with these disorders.

METHOD

The methodology of the Harvard/Brown study has been described previously . Briefly, 711 subjects between ages 18 and 65 years with one or more of the index diagnoses listed in the last paragraph were recruited from 11 clinical sites and have been followed with a structured protocol annually or semiannually since January 1989. After a complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. Excluded were patients with schizophrenia, organic mental disorder, or recent psychosis.

The Psychosocial Treatments Interview for Anxiety Disorders

(7,

8) was developed for the Harvard/Brown study and was used to track the psychosocial treatments received by Harvard/Brown subjects. This instrument has been validated and was shown to have good-to-very-good reliability

(8). The present analysis used the Psychosocial Treatments Interview for Anxiety Disorders to compare the frequency with which behavioral, cognitive, psychodynamic, and relaxation or meditation treatment modalities were received in 1991 and in 1995–1996. Data from 1995 and 1996 were combined, since some subjects were interviewed in only one of those years.

RESULTS

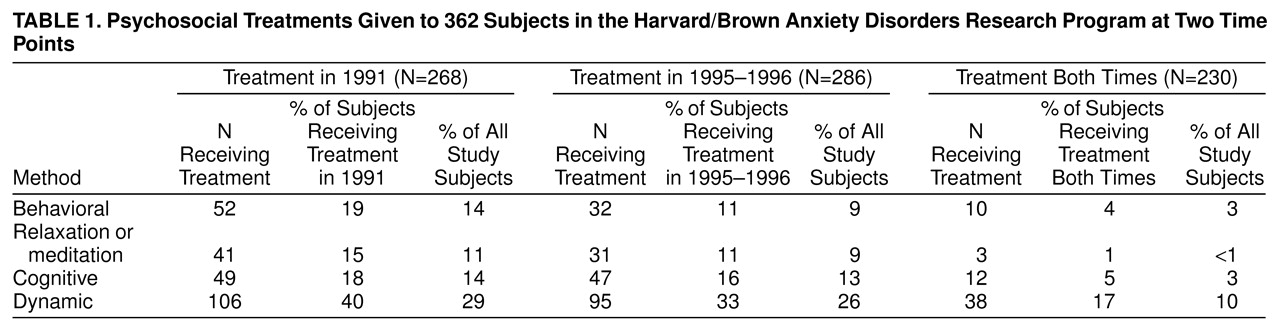

Of the 362 Harvard/Brown subjects for whom we have psychosocial therapy treatment data from both 1991 and 1995–1996, 74% (N=268) reported receiving psychosocial treatment in 1991, and 79% (N=286) reported receiving it in 1995–1996 (

table 1). The number of subjects who received the same treatment modality at both times was small. Two hundred thirty (64%) of the subjects reported receiving psychosocial therapy treatment in both periods (

table 1).

DISCUSSION

Consistent with our previous findings

(7,

8), the frequency of the use of behavioral and cognitive therapy remained low despite increased public and professional awareness of cognitive behavior therapy. Only 34% (N=123) of the subjects reported ever receiving one or more treatments of cognitive, behavioral, or relaxation or meditation therapy at either time point. Dynamic therapy remained the most consistently used psychosocial treatment, although it was received by a minority of subjects. Relaxation or meditation were infrequently received during both periods.

These findings are disturbing for clinicians who find data recommending the use of cognitive behavior therapy compelling

(2–

4,

6), because they describe a serious underuse of the methods for which there is strong evidence of efficacy. Simultaneously, our results point to a continued reliance on treatment methods which, although not proven ineffective, lack rigorous empirical validation.

A finding relevant to psychotherapists of any orientation concerns the frequency with which any verbal treatment was given in this study. Although the total percentage of subjects who received any psychosocial treatment increased slightly from 1991 (74%, N=268) to 1995–1996 (79%, N=286), the use of each of the four specific therapy modalities (i.e., behavioral, relaxation or meditation, cognitive, and dynamic) studied here declined over that period. Since only a small number of subjects received the same psychosocial treatment in both time periods, this might simply reflect subjects who received what they needed, benefited from it, and had different needs as time progressed. However, a less sanguine interpretation could be that clinicians and subjects are now working in a practice climate that places stricter limits on the availability of any purportedly definitive form of psychotherapy (i.e., those studied here), so that potentially effective treatments are not frequently used because of time, funding, or other constraints.

In an era emphasizing evidence-based practice, these findings are disconcerting. They are compatible both with the underuse of methods with proven efficacy, as other Harvard/Brown investigators have reported regarding psychopharmacologic treatment

(9), and with a general decline in the use of all specific verbal methods of treatment. If findings like these are replicated in other centers and with diagnoses other than those of anxiety disorders, clinicians should be concerned that the use of effective nonpharmacologic treatment strategies could decline further, to the detriment of effective patient care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Harvard/Brown Anxiety Disorders Research Program is conducted with the participation of the following investigators: M.T. Shea, Ph.D. (Veterans Administration Hospital, Brown University School of Medicine); J. Eisen, M.D., K. Phillips, M.D., and R. Stout, Ph.D. (Butler Hospital, Brown University School of Medicine); A. Massion, M.D. (University of Massachusetts Medical Center); M.P. Rogers, M.D. (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School); C. Salzman, M.D. (Massachusetts Mental Health Center, Harvard Medical School); G. Steketee, Ph.D. (Boston University School of Social Work); K. Yonkers, M.D. (University of Texas, Dallas); I. Goldenberg, Psy.D., and G. Mallya, M.D. (McLean Hospital, Harvard Medical School); T. Mueller, M.D. (Butler Hospital, Brown University School of Medicine); F. Rodriguez-Villa, M.D. (McLean Hospital, Harvard Medical School); R. Vasile, M.D. (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School); C. Zlotnick, Ph.D. (Butler Hospital, Brown University School of Medicine); and E. Fierman, M.D.

Additional contributions came from P. Alexander, M.D. (Butler Hospital, Brown University School of Medicine); J. Curran, M.D., and J. Cole, M.D. (McLean Hospital, Harvard Medical School); J. Ellison, M.D., M.P.H. (Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, Harvard Medical School); A. Gordon, M.D., and S. Rasmussen, M.D. (Butler Hospital, Brown University School of Medicine); R. Hirschfeld, M.D. (University of Texas, Galveston); J. Hooley, D.Phil. (Harvard University); P. Lavori, Ph.D. (Stanford University); J. Perry, M.D. (Jewish General Hospital, McGill University School of Medicine, Montreal); L. Peterson (Veterans Administration Hospital, Togus, Me.); J. Reich, M.D., M.P.H., and J. Rice, Ph.D. (Renard Hospital, Washington University School of Medicine); H. Samuelson, M.A. (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School); D. Shera, M.S. (Harvard School of Public Health); N. Weinshenker, M.D. (New Jersey Medical School); M. Weissman, Ph.D. (Columbia University); K. White, M.D.