Alcohol abuse and dependence are highly comorbid with other psychiatric diagnoses

(1,

4), especially among women

(4,

5). Unfortunately, very few people with alcohol abuse or dependence receive substance abuse or mental health services

(6,

7), and the use of such services is generally lower in this group than among those with almost any other psychiatric disorder

(7–

9). In particular, although female alcohol users appear to be more likely than male alcohol users to experience alcohol problems, they are less likely to use alcohol treatment services at substance abuse treatment facilities

(10–

12) or to enter treatment

(13). Further, the length of time between the onset of drinking, the onset of problem drinking, and adverse health consequences is shorter among women than men

(10).

Method

Data Source

Data were drawn from the public use file of the 1999 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse

(14). This survey is designed to provide national estimates of the use of licit and illegal substances by Americans 12 years old or older. The target population included residents of households, shelters, rooming houses, and dormitories, as well as civilians living on military bases. To increase the accuracy of drug use estimates, young people 12–25 years of age were oversampled. Survey respondents were interviewed about their use of a variety of substances, problems related to substance use and dependence, use of substance abuse services, and demographic characteristics.

The 1999 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse data collection method involved in-person interviews at the respondent’s place of residence and incorporated procedures developed to increase their cooperation and willingness to report drug use behavior honestly. These procedures combined computer-assisted personal interviews with audio computer-assisted self-interviews, which were designed to provide a private, confidential setting for answering sensitive questions.

This study of secondary data analysis of existing files was declared exempt from review by the Research Triangle Institute Institutional Review Board.

Study Sample

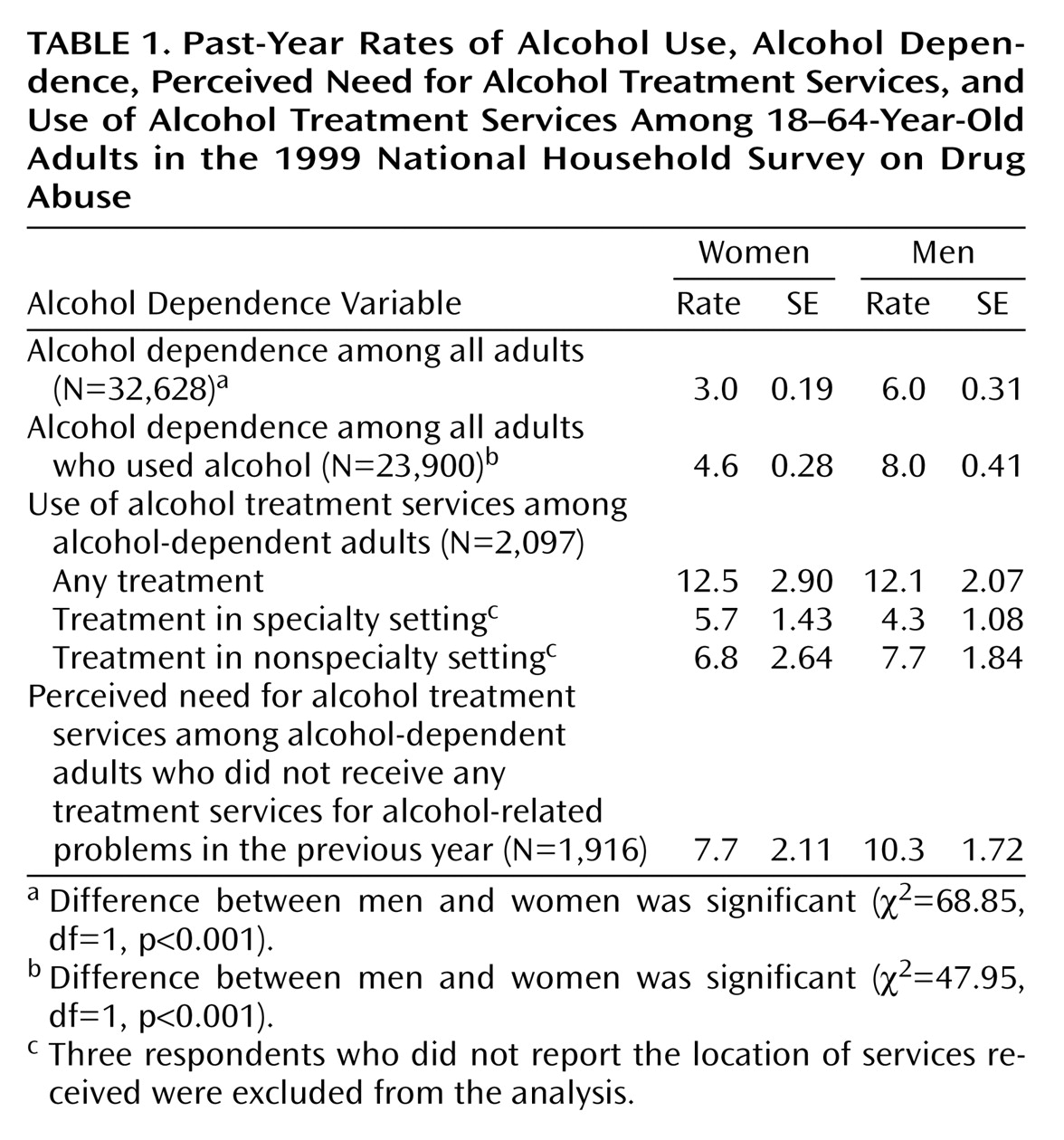

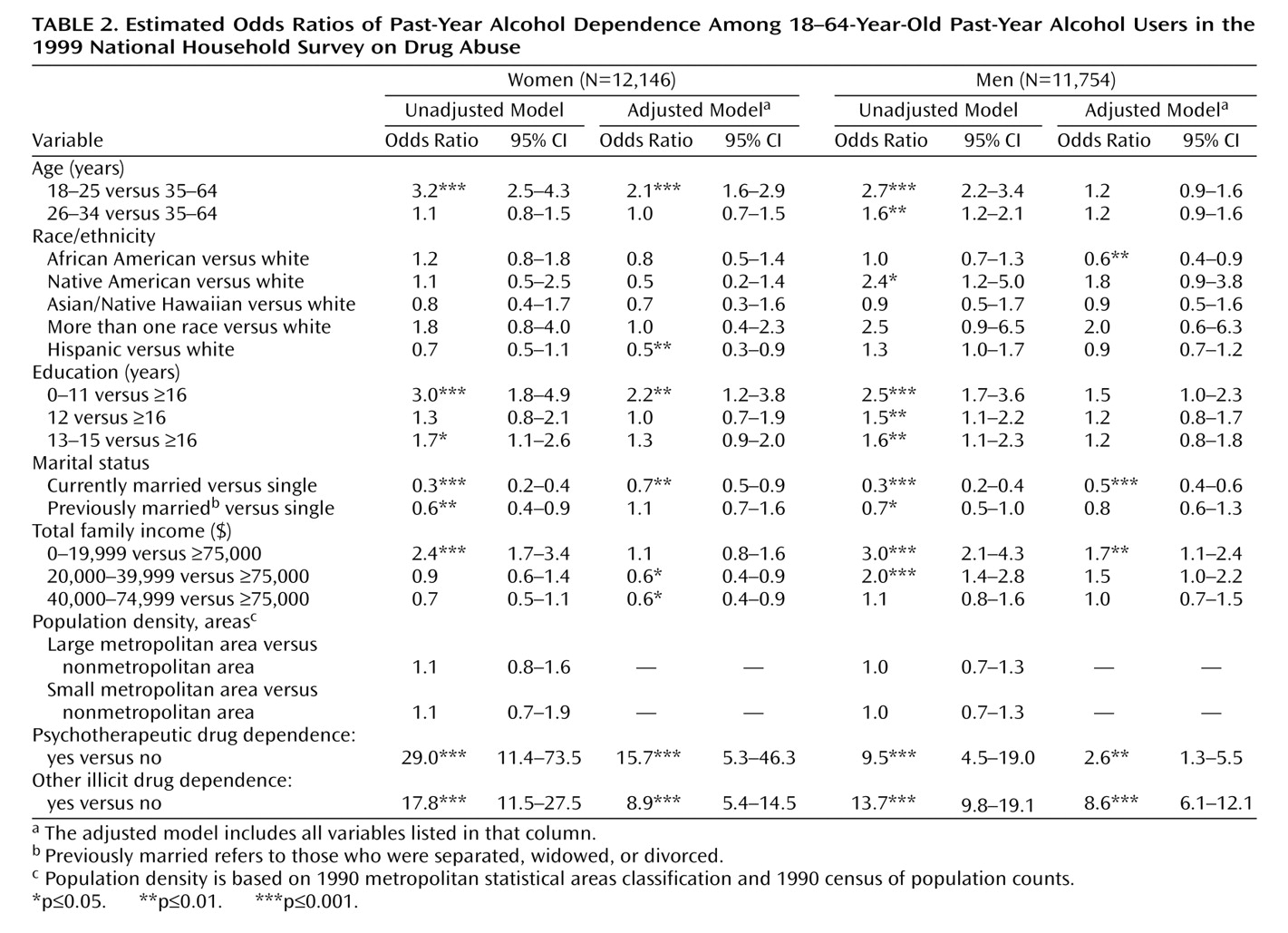

Of the 32,628 adults 18–64 years of age who were interviewed, 17,379 (53%) were women and 15,249 (47%) were men. Alcohol use in the past year was reported by 12,146 (70%) of the women and 11,754 (77%) of the men (χ2=89.89, df=1, p<0.001). Of the alcohol users, 40% were 18–34 years old, 9% were African American, 10% were Hispanic, 4% were other minority groups, 55% had at least some college education, 27% had never been married, and 42% had a family income of less than $40,000 (weighted percents). There were slight gender variations in education (10% of female alcohol users did not complete high school, compared with 14% of male users) and marital status (24% of female users had never been married, compared with 29% of male users).

Definitions of Variables

Alcohol dependence

The 1999 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse

(14) included a series of questions to assess alcohol dependence in the past year based on seven DSM-IV criteria: 1) tolerance, 2) withdrawal, 3) inability to cut down or stop alcohol use, 4) spending a great deal of time obtaining or drinking alcohol or recovering from its effects, 5) reducing or giving up important activities because of alcohol use, 6) using alcohol more often than intended, and 7) having physical or psychological problems because of alcohol use. Respondents who met three or more of these criteria in the previous year were classified as alcohol dependent.

Dependence on psychotherapeutic medication referred to dependence on any nonmedical use of prescription-type stimulants, sedatives, pain relievers, and tranquilizers, excluding over-the-counter drugs. Other illicit drug dependence referred to dependence on marijuana, cocaine, hallucinogens, heroin, or inhalants in the past year.

Treatment services

Use of alcohol treatment services was defined broadly as use in the past year of any service for alcohol-related problems at any location. We defined two types of treatment locations—specialty and nonspecialty—on the basis of respondents’ answers to a question about the main place where they received their most recent treatment services. A specialty setting refers to residential alcohol/drug rehabilitation facilities, nonresidential alcohol/drug rehabilitation facilities or programs, and mental health facilities or centers. A nonspecialty setting includes private doctors’ offices, hospitals, jails or prisons, court-sponsored programs, self-help groups, church-run programs, schools, workplaces, or community/city programs.

Perceived need for services

The subgroup of respondents who reported that they did not receive treatment or counseling for their alcohol use in the previous year were asked if they needed alcohol-related treatment or counseling during this period.

Demographics

We examined the following respondent characteristics: age, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, total family income, and population density of the area where the respondent lived

(14). For the analysis of perceived need for alcohol treatment services and use of treatment services, we also determined how many children younger than 18 years of age were living with respondents because of the potential association with use of treatment services among women

(15).

Statistical Analyses

The National Household Survey on Drug Abuse used a multistage probability sampling method to select participants. To ensure the representativeness of the sample, analysis weights were developed to adjust for variation in household selection, nonresponse, and poststratification of the selected sample to census data

(16). Analyses were conducted with SUDAAN software to adjust for the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse’s complex multistage survey design

(17). All percentages reported in this paper are weighted estimates; sample sizes are unweighted.

We began by calculating the rates and correlates of alcohol dependence among alcohol users. Among the subset of respondents who were alcohol dependent, we determined the extent and correlates of their use of alcohol treatment services and, in those who did not use these services, their perceived need for treatment. We then conducted logistic regression procedures to identify 1) the characteristics of alcohol dependence, 2) correlates of use of alcohol treatment services, and 3) correlates of perceived need for such services. We used a stepwise method to select variables to be included in the final logistic regression model and determined their respective odds ratios. An adjusted odds ratio denotes the strength and direction of the association between a response variable (e.g., use of treatment services) and a given correlate, while controlling for other potentially confounding characteristics. An odds ratio greater than one indicates a positive association between the two variables; an odds ratio smaller than one denotes an inverse association.

Discussion

An estimated 3% of all women and 6% of all men in the 1999 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse met criteria for past-year alcohol dependence. Our prevalence estimates of alcohol dependence and use of treatment services are similar to those of other studies. Findings from the National Comorbidity Survey of subjects 15–54 years old

(4) indicated that 2% of women and 7% of men met criteria for alcohol dependence in the previous year. The National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey

(6) found that 10% of Americans 18 years old or older with alcohol abuse or dependence received alcohol treatment services in the previous year.

A remarkably high proportion of alcohol-dependent women as well as men did not use alcohol treatment services

(6) and did not perceive a need for such services. Only two of 25 alcohol-dependent women who did not receive services reported a need for help. The National Comorbidity Survey

(19) also found that the proportion of people with a substance use disorder who reported a perceived need for help was low (14%). These findings support other findings

(18,

20) that there is a long lag time between the onset of alcohol problems and initial treatment contact with a health care provider (approximately a decade). Thus, many persons may not have sought help until their alcohol use resulted in substantial problems in their lives

(20).

Many alcohol abusers do not seek treatment services because they do not perceive their drinking as a problem or because they prefer to handle it on their own

(21,

22). Our study and others

(21,

22) suggest that alcohol-dependent individuals may benefit from targeted educational interventions that increase their knowledge about the symptoms of alcohol abuse or dependence, its consequences, and the availability and effectiveness of treatment services.

Many people who use alcohol treatment services are seen in a nonaddiction treatment setting, which points to the vital role of general physicians and non-health-care agencies in the delivery of alcohol treatment services. However, substance abuse and/or mental health care provided by general medical providers or primary care physicians may be inadequate

(23,

24). For instance, comorbid mood and anxiety disorders are more common among women with alcohol abuse or dependence than among their male counterparts

(4,

5), but general medical providers may fail to adequately assess the possibility of comorbid mental health or substance abuse problems and non-health-care agencies may be unable to provide a full-scale psychiatric assessment

(24).

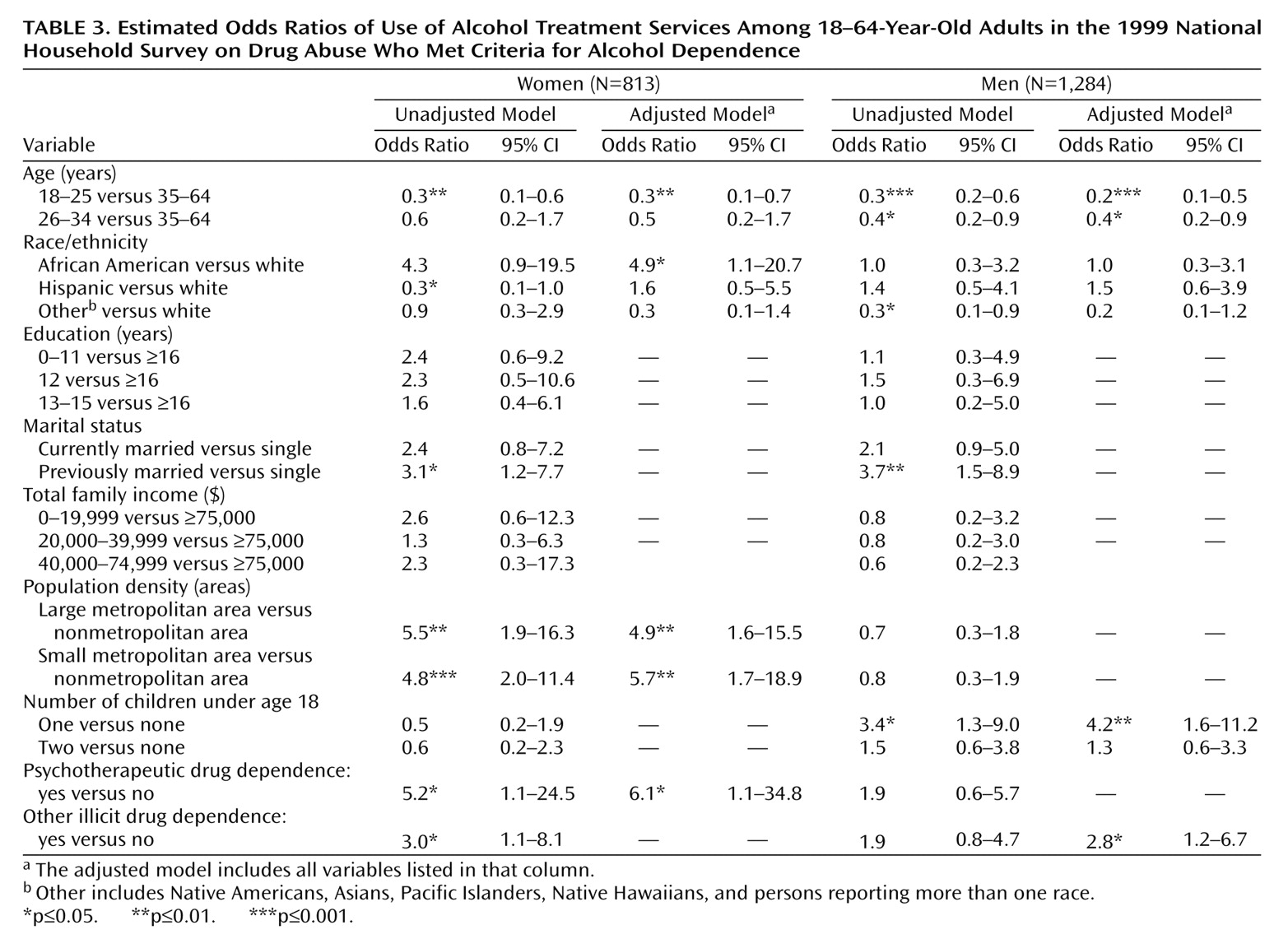

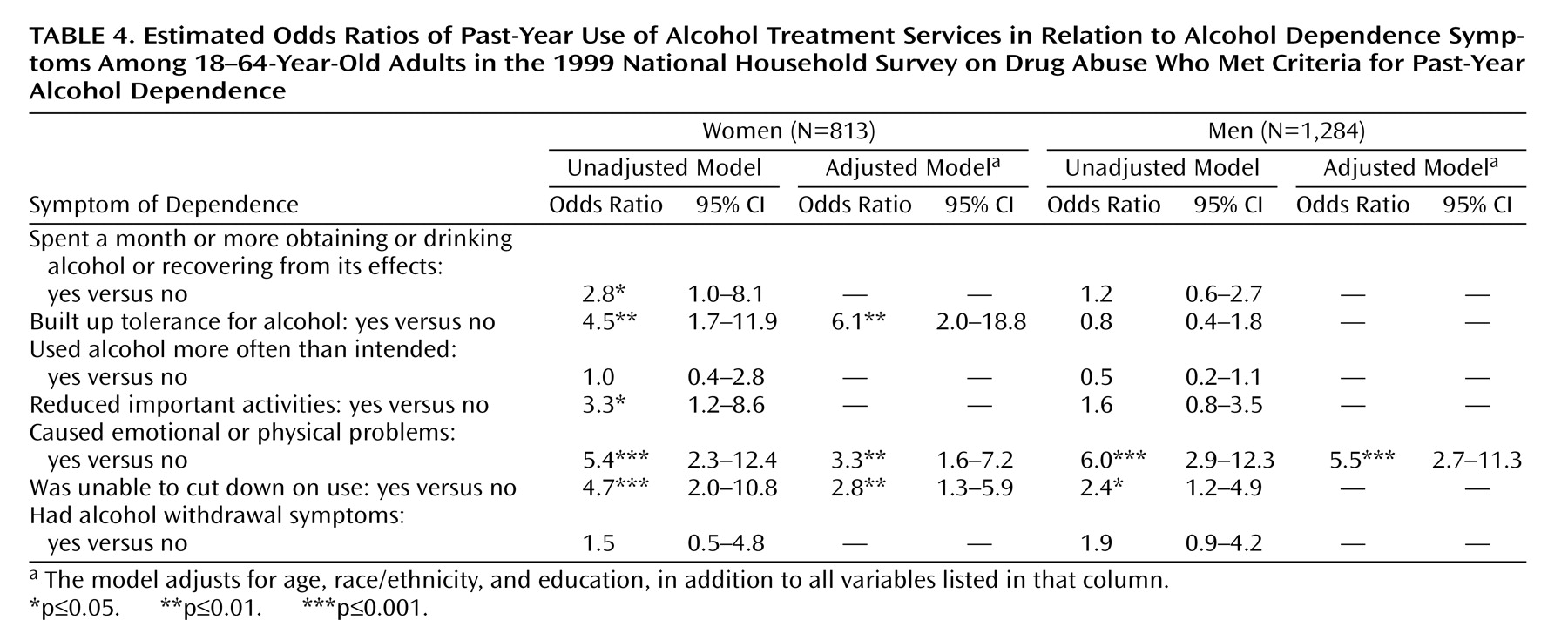

Alcohol dependence among alcohol users was highly associated with drug dependence, particularly dependence on psychotherapeutic medications for women and other drug dependence for men. Among alcohol-dependent adults, use of treatment services was strongly related to comorbid dependence on psychotherapeutic medications in women and comorbid other drug dependence in men. These findings suggest that use of treatment services is determined by the severity of alcohol dependence and its immediate consequences (e.g., comorbid alcohol-related emotional/medical problems), which may prompt health care providers or others to notice them

(25–

27).

Women with alcohol problems are less likely than men to receive support from family or friends to enter treatment

(28) and more likely to seek help in a nonaddiction treatment setting

(11,

12). However, our findings suggest no significant gender differences in use of treatment services, receipt of services in a specialty treatment setting, and perceived needs for treatment. Weisner and Matzger

(27) also found no gender difference in entry to alcohol/drug treatment. These findings may reflect a recent change in women’s access to substance abuse care, perhaps caused by reductions in stigma, increased awareness of alcohol problems, or greater availability of women-focused treatment programs

(29,

30).

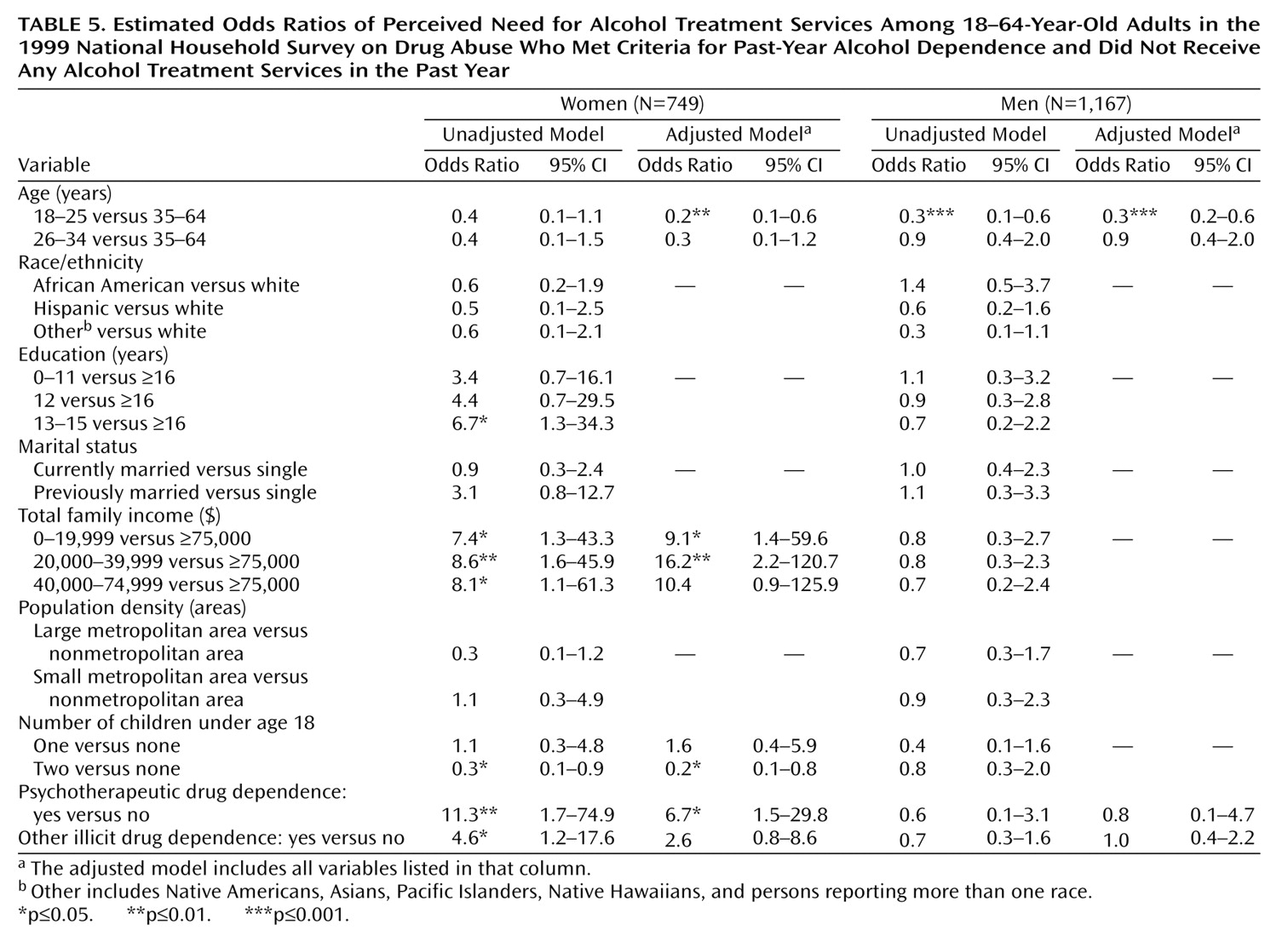

For both genders, age is a significant correlate of use of treatment services and perceived need for treatment. Young adults are most likely to report a recent substance use disorder

(2). Unfortunately, we found that young alcohol-dependent adults used fewer services and were less likely to perceive a need for services. Hajema et al.

(31) also found that younger adults used fewer alcohol treatment services, independent of the severity of their alcohol problems. Heavy drinking among young adults may be more tolerated by peer groups and considered a transitional stage before the assumption of adult responsibilities

(31). Young drinkers typically have a shorter duration of problem drinking than older drinkers and are more likely to claim that they can manage their drinking behavior without treatment.

We also found that African American alcohol-dependent women were more likely than their white counterparts to use treatment services

(32) and that women with the highest income were less likely than those with lower incomes to perceive a need for help. Women in alcohol/drug treatment, especially African American women

(33), tend to have lower incomes than men

(11,

34). Yet African American women and those with lower incomes are least likely to complete treatment

(30,

34). Entry into alcohol treatment may generate some personal and social losses because of stigma, separation from family, and negative job-related consequences

(28). High-income women who do not seek alcohol treatment may deny their alcohol problems because of fear of stigma and other social losses but may seek other mental health services. In fact, socioeconomically disadvantaged people are most likely to enter public alcohol treatment programs, while higher-income people tend to enter private treatment sectors through workplace referrals

(29).

Although we did not observe any gender differences in the use of treatment services, women still may face unique psychosocial and program-related barriers to entering and remaining in treatment

(12,

28,

35,

36). Men, especially married men, are more likely than women to receive support from family and friends to enter alcohol treatment

(28). Women, especially those with children, experience more shame than men and worry about losing custody of their children and failing to fulfill childcare responsibilities when entering treatment

(37–

40). McMahon et al.

(15) found a negative relationship between the number of children and the number of contacts for drug abuse treatment. We observed that alcohol-dependent women who had two or more children living with them were less likely to perceive a need for treatment than those without children. Available addiction treatment programs may not be designed to meet the special needs of women

(41,

42). Women in substance abuse treatment typically view themselves as having a unique set of needs that tend to go unmet

(41).

These findings should be interpreted with some caution. First, the annual National Household Survey on Drug Abuse uses a cross-sectional design and relies on respondents’ self-reports. Our findings could be influenced by some memory and reporting biases. Nonetheless, the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse methodology has produced more valid estimates of substance use than telephone surveys

(43). Further, studies have found self-reported substance use to be valid, especially among those with substance-related problems

(44,

45). Second, the lack of available data on mental health problems, quality of care obtained, and DSM-IV criteria for alcohol abuse requires us to exclude these characteristics from our analyses.

It appears that only those individuals with the most severe alcohol and drug problems receive treatment or come to the attention of institutions or others that would facilitate their treatment entry

(46). Young adults, white women, and those without comorbid drug dependence may underutilize alcohol treatment services and may be less likely to be identified by others as having alcohol problems. Barriers to use of treatment services and identification of alcohol problems deserve further investigation. For women who received services, the quality of the care received, the setting, and the level of appropriateness of their treatment deserve further examination.