During the past several years, experts in the treatment of depression have emphasized the importance of striving for remission

(1,

2). This recommendation stems from studies demonstrating that the presence of residual symptoms in treatment responders is associated with a greater likelihood of recurrence of a full depressive syndrome

(2).

In antidepressant efficacy trials, remission is usually defined as scoring below a threshold value on an interviewer-rated measure of depression severity such as the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

(3). It has been recommended that measures such as the Hamilton depression scale be used by clinicians to evaluate remission, although the time demands of clinical practice limit the feasibility of this suggestion. Self-report questionnaires are a cost-effective option for thoroughly, systematically, reliably, and validly evaluating clinical status because they are inexpensive in terms of the professional time needed for administration.

In the present report from the Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services (MIDAS) project, we derived a cutoff on a self-report depression questionnaire corresponding to the most widely used definition of remission used in antidepressant efficacy trials (a score ≤7 on the 17-item Hamilton depression scale). Derivation of a valid cutoff on a brief depression questionnaire corresponding highly with the Hamilton depression scale definition of remission can enable clinicians to efficiently determine depressed patients’ remission status during the course of ongoing outpatient treatment.

Method

Participants were 303 psychiatric outpatients being treated for a DSM-IV major depressive episode in the outpatient practice of Rhode Island Hospital’s Department of Psychiatry.

The study group included 114 men (37.6%) and 189 women (62.4%) who ranged in age from 18 to 79 years (mean=42.9, SD=12.7). Almost half of the subjects were married (47.9%, N=145); the remainder were single (23.4%, N=71), divorced (19.8%, N=60), separated (5.6%, N=17), widowed (2.0%, N=6), or living with someone as if in a marital relationship (1.3%, N=4). The Rhode Island Hospital’s institutional review committee approved the research protocol, and all patients provided written informed consent.

Diagnoses were based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV

(4). Patients were rated by the first two authors on the 17-item Hamilton depression scale. Two hundred sixty-seven patients (88.1%) completed the self-report depression questionnaire described below. There were no demographic differences between patients who did and did not complete the scale.

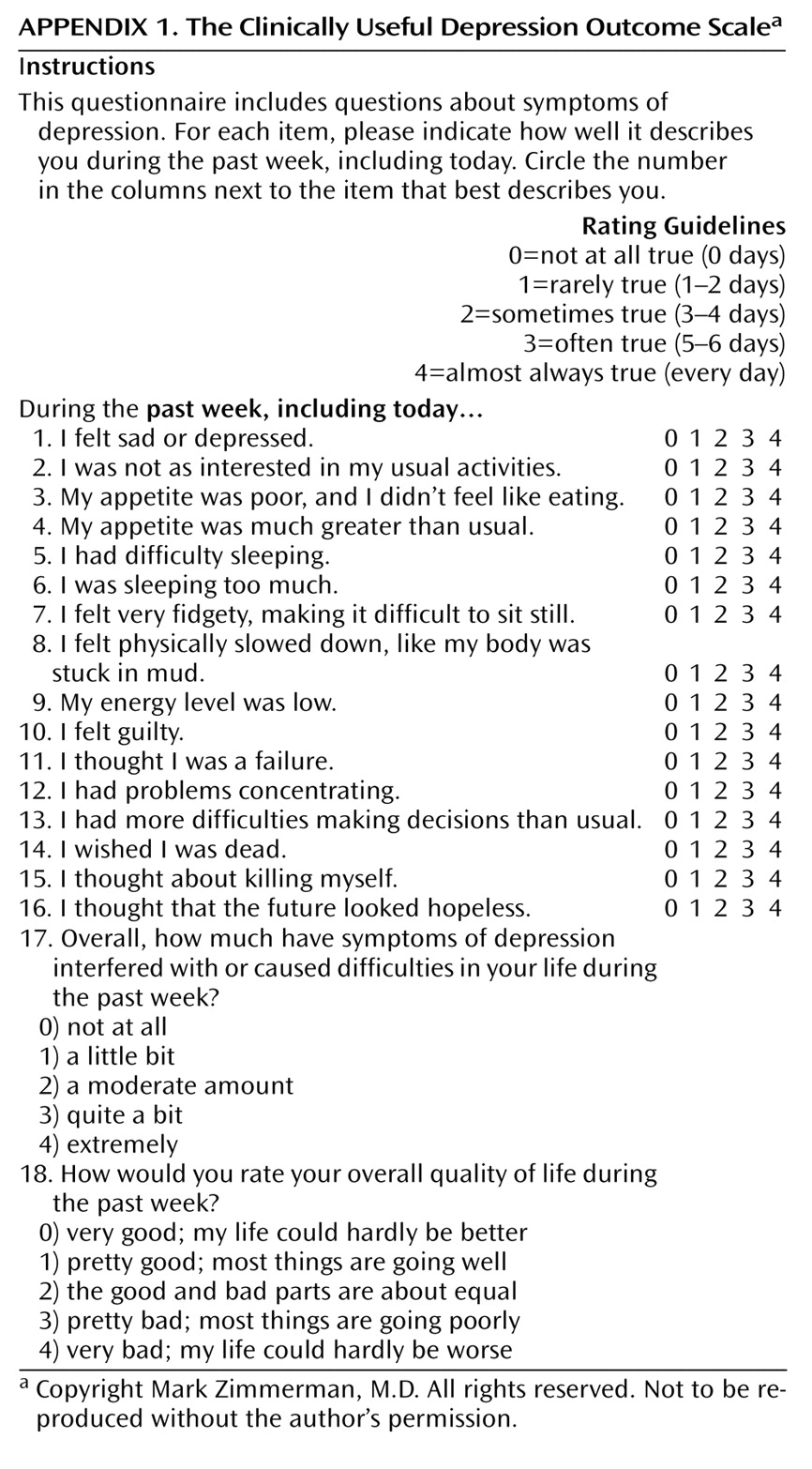

As part of the MIDAS project, we have developed several disorder-specific, interview-based, and self-report screening and outcome measures that were designed to be readily incorporated into routine clinical practice. One such measure is the CUDOS, which contains 18 items assessing each of the DSM-IV inclusion criteria for major depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder as well as psychosocial impairment and quality of life. The scale is reprinted in

Appendix 1. A Likert rating of the symptom statements was preferred in order to keep the scale brief. Scales that assess symptoms with groups of four or five statements are thus composed of 80 or more statements and take respondents 10–30 minutes to complete. This was considered too long for regular use in clinical practice in which the scale would be administered at all follow-up visits. The amount of time to complete the CUDOS during a follow-up visit was recorded in 50 patients. All but two patients completed the scale in less than 3 minutes (mean=102.7 seconds, SD=42.7). Studies of the reliability and validity of the CUDOS indicate that the scale has strong psychometric properties (internal consistency reliability coefficient was 0.90; test-retest reliability coefficient was 0.92 [Zimmerman et al., unpublished manuscript]).

The purpose of the present study was to determine the cutoff on the CUDOS that corresponded most closely with a 17-item Hamilton depression scale score of 7. We examined the ability of the CUDOS to identify patients who were in remission, according to the Hamilton depression scale across the range of CUDOS cutoff scores by conducting a receiver operating curve analysis. A receiver operating curve is a plot of a measure’s sensitivity versus one minus the specificity at each cutoff score.

Results

The mean score on the 17-item Hamilton depression scale for the 267 depressed outpatients was 11.1 (SD=8.4). Based on a cutoff score of 7, more than one-third of the patients were in remission (41.6%, N=111). For the CUDOS, the mean score was 22.9 (SD=14.7). The Pearson correlation between the Hamilton depression scale and the CUDOS was 0.89.

In the receiver operating curve analysis, the area under the curve was significant (area under the curve=0.95, p<0.001). The sensitivity, specificity, and overall classification rate of the CUDOS for identifying remission, according to the Hamilton depression scale threshold of ≤7, was examined for each CUDOS total score. The maximum level of agreement with the Hamilton depression scale definition of remission that provided the best balance of sensitivity and specificity occurred at a cutoff of <20 (sensitivity=87.4%, specificity=87.8%, total agreement=87.6%, kappa=0.75).

Discussion

The optimal delivery of treatment for depression depends on monitoring outcome; therefore, precise, reliable, valid, informative, and user-friendly measurement is key to assessing the course of treatment in routine clinical practice. The Hamilton depression scale is the most frequently used clinician-rated depression symptom severity scale used in antidepressant efficacy trials; however, it is not practical to use the Hamilton depression scale in clinical practice because it requires too much time and effort to complete. Self-report questionnaires represent a practical option for thoroughly and objectively evaluating the course of treatment.

In the present study, we demonstrated that a cutoff on a self-report depression scale could be derived that corresponded highly to the commonly used definition of remission on the Hamilton depression scale. Because the CUDOS takes no more than 2 to 3 minutes to complete, it is minimally burdensome for patients to fill out. The scale can thus be routinely administered at follow-up visits in the same way that blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and weight are routinely assessed in primary care offices for patients who have those chronic conditions. Other brief scales, such as the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale, can also be used for this purpose, and future research should determine the appropriate cutoff score to identify remission.

A limitation of the study is that our gold standard definition of remission, a cutoff score of 7 on the 17-item Hamilton depression scale, has been questioned by some investigators who have suggested that this cutoff score is too high

(5,

6). A cutoff of 7 on the Hamilton depression scale allows for the presence of residual symptoms, and some patients even qualify for a depressive disorder diagnosis

(5).

Correspondingly, the CUDOS cutoff of 20 includes patients with some depressive symptoms. If researchers determine that another cutoff on the Hamilton depression scale is more valid, another cutoff on the CUDOS may be more appropriate. Also, the focus of this article has been on a narrow perspective of remission, according to a score on a measure that assesses symptom levels over the week before the evaluation. Others factors that can be used to define remission, such as good psychosocial functioning, were not considered. However, the goal of the present study was to derive a cutoff score on a self-report scale that corresponds to the most frequently used interviewer-based measure of remission. This aim has been successfully achieved and thereby provides practicing clinicians with a tool that can be easily incorporated into their practice in order to determine whether patients are in remission from depression.