Patients

The patients were referred to the study therapists by primary care physicians, private specialist practices, and public outpatient departments. None were solicited for research. These patients wanted exploratory psychotherapy because of depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, personality disorders, and interpersonal problems. Patients with psychosis, bipolar illness, organic mental disorder, or substance abuse were excluded. Participants were also excluded if mental health problems had caused sick leave for several periods longer than 1 year.

After taking history and assessment of background variables by the patients’ therapists, each patient had a 2-hour psychodynamic interview, modified after Malan

(8) and Sifneos

(9), with an independent evaluator. The interview was audiotaped. Several of the other clinicians, including the therapist, listened to the interview. Based on the interview, the Quality of Object Relations Scale

(10), the Psychodynamic Functioning Scales

(11), and the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale were independently rated by at least three clinicians. The patients completed the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems-Circumplex version and Symptom Checklist-90-R. No structured interview was used in this study to determine axis I diagnoses. The diagnoses were discussed until consensus was reached, based on all available material, according to the criteria of DSM-III-R. Axis II diagnoses were determined by the patients’ therapists using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II)

(14) . All the therapists had prior training in using SCID-II. In addition, the general diagnostic criteria for (any) personality disorder (DSM–IV, p. 633) were discussed in each case, based on all available material, until consensus was reached.

After the procedures had been fully explained, written informed consent was obtained from each participant. Fifty-two patients were assigned to dynamic psychotherapy with a low to moderate use of transference interpretations (the transference group). Forty-eight patients were assigned to dynamic psychotherapy of the same kind but without transference interpretations (the comparison group). The patients were not informed about which technique was studied and the hypotheses of this study. Standard power calculation (endpoint analysis) indicated that moderate effect sizes (effect size: 0.55) could be detected for alpha levels of 0.05 with a power of 0.80. An alpha level of 0.10 was decided for the moderator analyses and the subgroup analyses in order to balance the risk of type II errors.

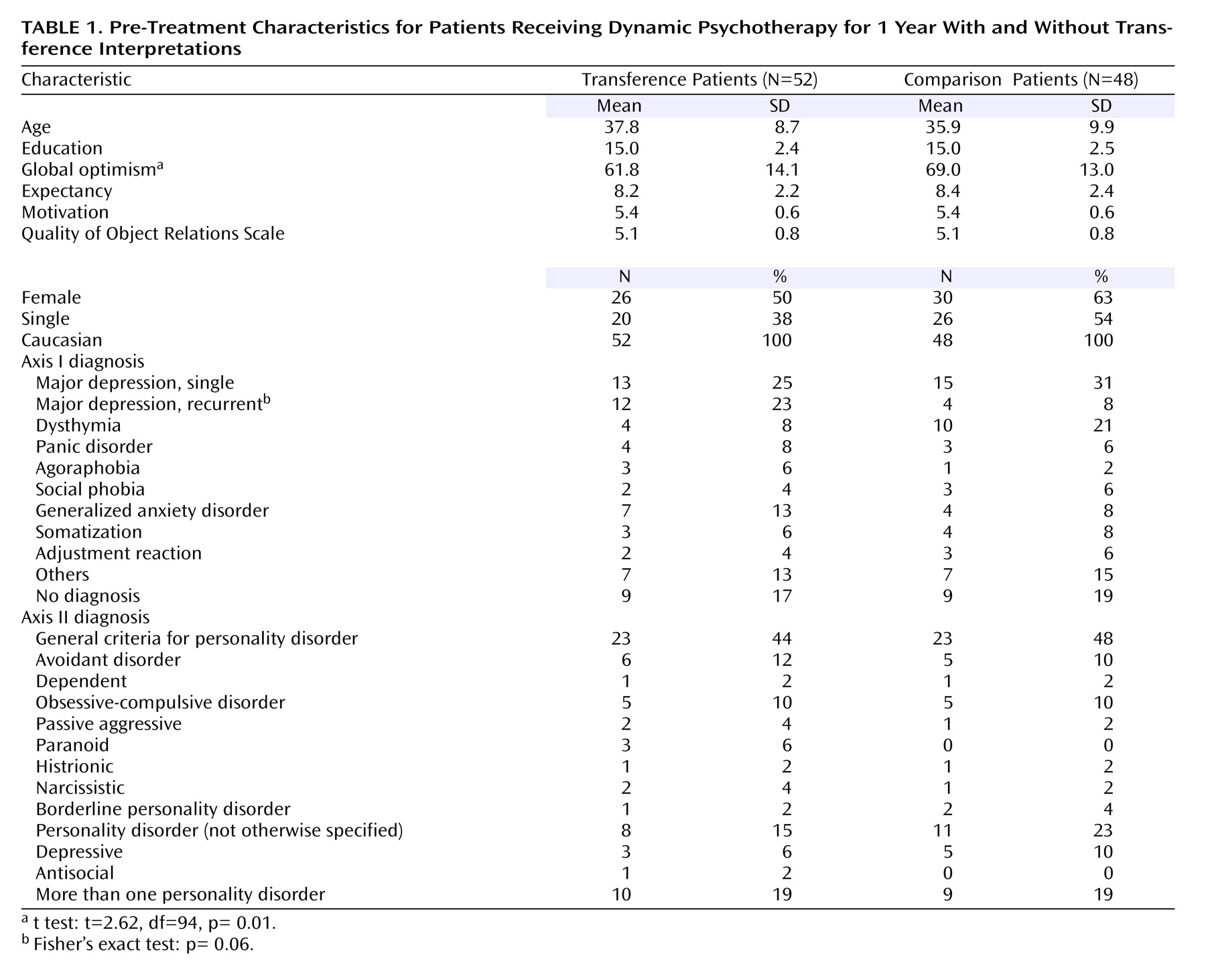

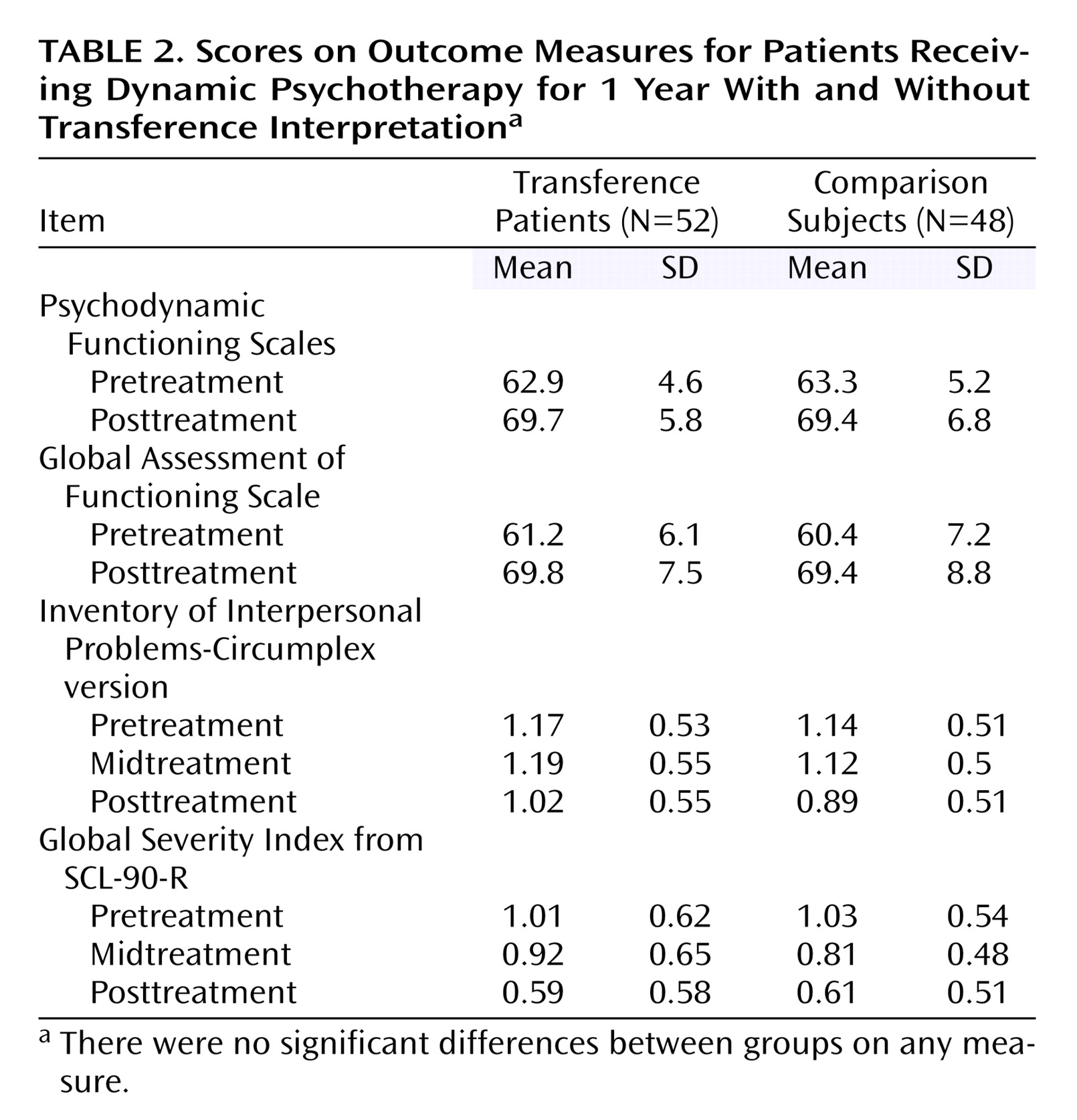

Table 1 presents the pretreatment patient characteristics and shows that the random assignment procedure was successful—that is, we could demonstrate no differences between the groups on the pretreatment variables, including demographic, diagnostic, initial severity, personality, motivation, and expectancy. Patients in the comparison group rated themselves as somewhat more optimistic on a visual analogue scale (0–100 mm). In both groups, patients reported that their main target problem lasted, on average, approximately 9 years. One year after the start of therapy, the patients were interviewed again by a blind, independent clinician.

Therapists and Evaluators

Patients were assigned to one of the seven therapists, depending on availability. The clinical evaluators and therapists consisted of six psychiatrists and one clinical psychologist, all of whom had 10–25 years of experience in practicing psychodynamic psychotherapy. Four of them were certified psychoanalysts. In the pilot phase of this study, the therapists were trained for as long as 4 years in order to be able to administer treatment with a moderate frequency of transference interpretations (1–3 per session) as well as treatment without such interpretations with equal ease and mastery. Each therapist treated from 10 to 17 patients in the main study. All therapists treated patients from both groups. Since the therapists were not blind to the group to which their patients belonged and also served as clinical evaluators of other patients, no therapist ratings (a therapist rating his or her own patients) were included in any of the statistical analyses.

The random assignment of patients was conducted after the pretreatment ratings were completed. Only the patients’ therapists learned the result of the random assignment procedure. The random assignment code was kept on a separate computer, which belonged to our research assistant. The other clinicians remained blind to the group to which the patient belonged. Before the posttreatment evaluation, three of the clinicians rated two audiotaped sessions from each of the first 30 patients regarding treatment fidelity. The raters may have guessed from the content the group in which the patient belonged. We believe that remembering group assignment from listening to anonymous audio tapes weeks or months before the posttreatment evaluation is very unlikely. We cannot, however, maintain that it never happened. For some patients, blinding may have been compromised.

Treatments

The patients were offered 45-minute sessions weekly for 1 year. All sessions were audiotaped. One patient assigned to the comparison group withdrew from the study after the random assignment. Four patients, all of them in the comparison group, dropped out of therapy before session 15. Treatment length, without the dropouts, was equal in the transference and comparison groups (34 [SD 6.1] and 33 [SD 6.6] sessions on average).

A treatment manual for this study was published in 1990

(15) . A different manual for process ratings of audiotaped sessions included the following scales: General Interpersonal Skill, Interpretive and Supportive Technique Scale

(16), and Specific Transference Technique Scales (Høglend 1995, unpublished manual). All items from these scales have similar rating instructions and format (i.e., Likert scales of 0–4).

For the transference group, the following specific techniques were prescribed:

1) The therapist was to address transactions in the patient-therapist relationship.

2) The therapist was to encourage exploration of thoughts and feelings about the therapy and therapist.

3) The therapist was to include himself explicitly in interpretive linking of dynamic elements (conflicts), direct manifestations of transference, allusions to the transference, and repercussions on the transference by high therapist activity.

4) The therapist was to encourage the patient to discuss how he or she believed the therapist might feel or think about him or her.

5) The therapist was to interpret repetitive interpersonal patterns (including genetic interpretations) and link these patterns to transactions between the patient and the therapist. In the comparison group these techniques were proscribed. In this patient group, the therapist consistently used material about interpersonal relationships outside the therapy as the basis for similar interventions (extratransference interpretations).

On average, four or five full sessions from each therapy were rated by three of the clinicians, who were blind to the group to which the patient belonged (sessions N=447). With two raters per session, interrater reliability coefficients were generally high, from 0.70 to 0.97, for all the process scales

(17) . The specific transference techniques (five items) differentiated significantly between the treatment groups. The level in the transference group was 8.1 (SD=3.2) versus 0.9 (SD=1.1) in the comparison group (t=15.2, df=64, 90, p<0.0005). Termination of therapy was addressed and interpreted in both groups. Analysis of other interpersonal relationships (extratransference) (five items) was given more space and emphasis in the comparison group. The level was 13.5 (SD=1.6) in the comparison group versus 12.0 (SD=1.6) in the transference group (t=4.6, df=94, p<0.0005). We could detect no differences in the levels of the scales of General Interpersonal Skill (eight items) and Supportive Interventions (seven items) between the two treatment groups.

Both treatments were mainly exploratory in nature. We performed several linear mixed-model analyses with time, time x treatment, therapist, and time x treatment x therapist as fixed effects. We could not detect any significant therapist effects. It should be noted, however, that this study did not have the power to detect any small or moderate therapist x treatment interactions.

Measures

Since none of the instruments for measuring clinician-rated psychodynamic changes was considered sensitive enough to capture statistically significant changes during brief therapy, the Psychodynamic Functioning Scales were developed in the pilot phase of this study

(11) . The six scales have the same format as the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale and measure psychological capacities over the last 3 months. These scales are as follows: quality of family relationships, quality of friendships, quality of romantic/sexual relationships, tolerance for affects, insight, and problem solving capacity. Aspects of content validity, internal domain construct validity, interrater reliability, discriminant validity from symptom measures, and sensitivity for change in brief dynamic psychotherapy were tested

(11,

18,

19) . With at least three clinical raters on each evaluation at pretreatment and posttreatment, the interrater reliability estimates for average scores used in this study were approximately 0.90 for the Psychodynamic Functioning Scales and the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale. The total mean score of the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems-Circumplex version

(12) was used to assess patients’ self-reported interpersonal problems. The measure of self-reported symptom distress was the Global Severity Index of the Symptom Checklist-90-R

(13) .

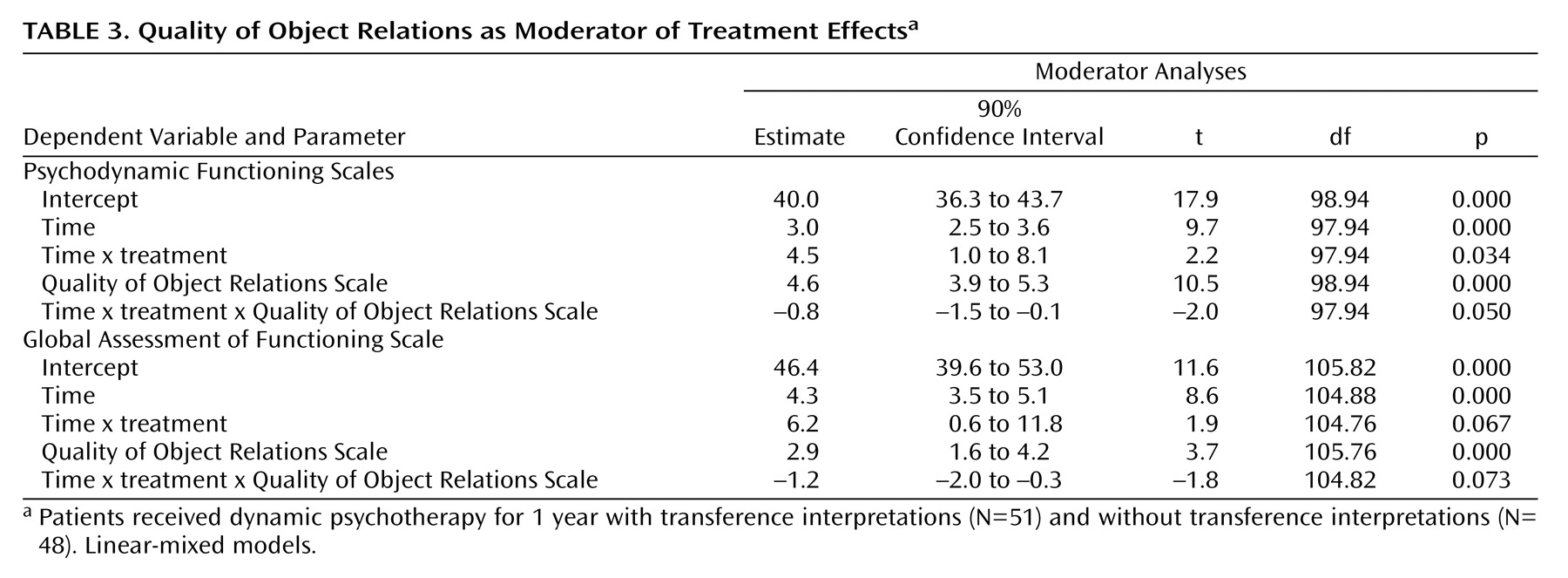

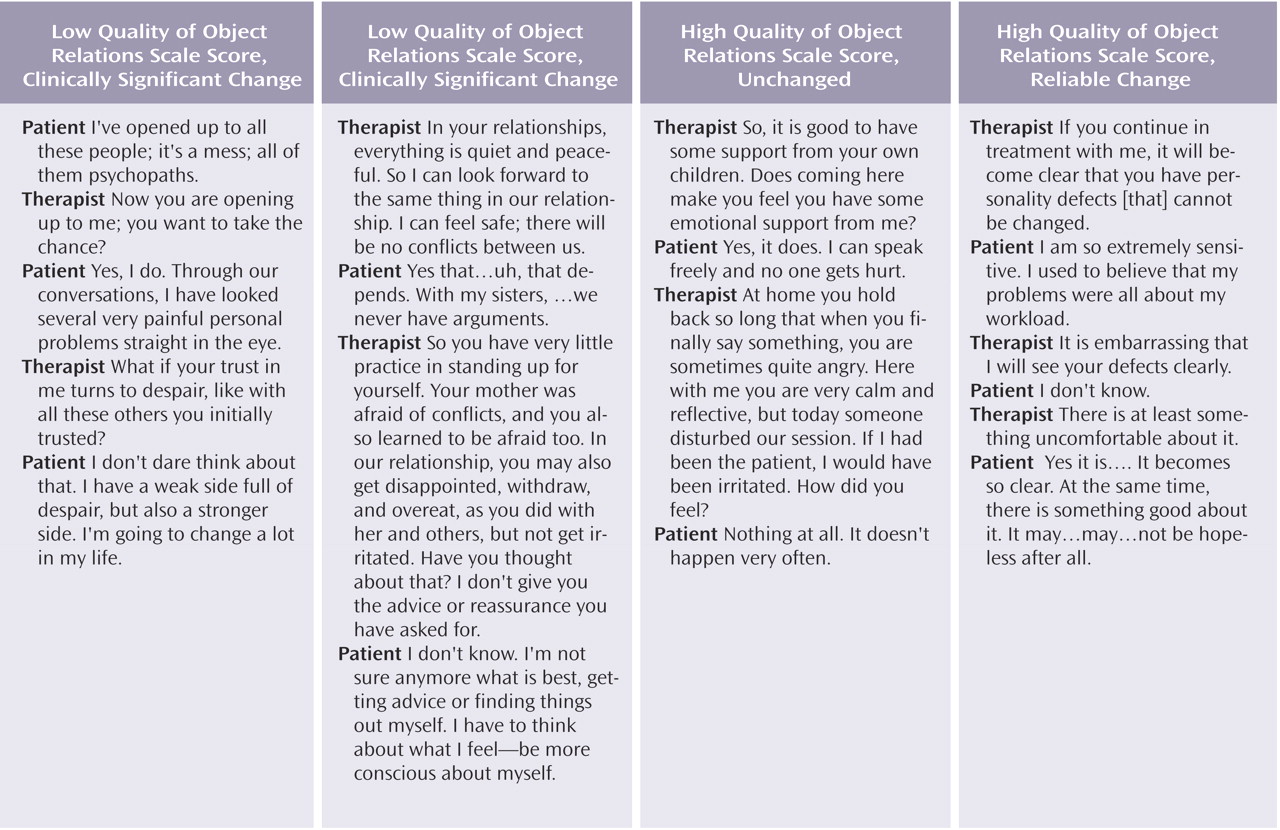

Two patient characteristics were chosen a priori as possible moderators of treatment effects

(20) : the Quality of Object Relations Scale score and the presence versus absence of personality disorders. The Quality of Object Relations Scale score was determined from the following three 8-point scales: evidence of at least one stable and mutual interpersonal relationship in the patient’s life, history of adult sexual relationships, and history of nonsexual adult relationships. The Quality of Object Relations Scale measures the patient’s lifelong tendency to establish certain kinds of relationships with others, from mature to primitive. Interrater reliability for average scores of three raters was 0.84 in this study. The predetermined cutoff score for high versus low Quality of Object Relations Scale scores was 5.00.

Statistical Analysis

One outlier patient was deleted from all analyses of longitudinal data. It became clear during treatment that the patient abused sedatives and painkillers. The patient was a 3.4 standard deviation or more from the distribution on three of the four outcome variables. Including this case produced significantly poorer goodness-of-fit measures (change in –2 log likelihood). All longitudinal analyses were performed on the sample of 99 patients. We used linear-mixed models to analyze longitudinal data (SPSS version 12.0)

(21) . “Subject” was treated as random effect. Time and intercept were treated as both random and fixed effects, while treatment group was treated as fixed effect only. An unstructured covariance matrix provided the best goodness-of-fit measures for the self-report outcome measures, with three data points. For the clinical outcome measures, with only two data points, a variance components covariance matrix was used. The fixed effects were intercept, time, and time x treatment

(22) . By using this model, we assumed that group means at baseline were equal by design. The statistical test of a treatment effect is time x treatment. The fixed effects in the moderator analyses were time, time x treatment, moderator, and time x treatment x moderator. In this model, the moderator is time-invariant and may also have an effect at baseline. The statistical test of a moderator effect is time x treatment x moderator.

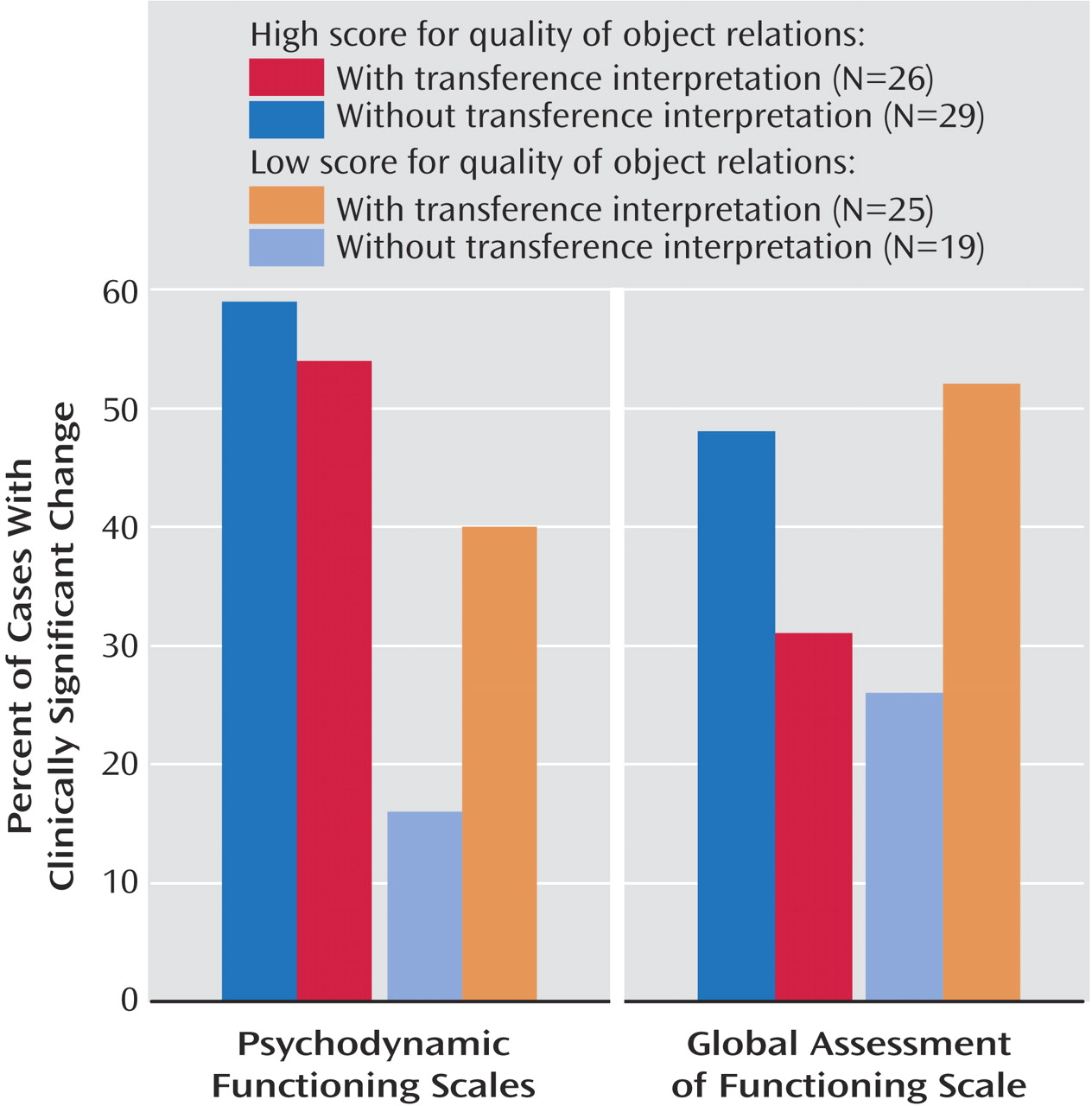

Clinically significant change has been proposed as a method for reporting results in treatment studies that signify clinically meaningful improvement for the single patient. In this study reliable change was calculated according to formulas from Jacobson and Truax

(23) . Cutoff scores for nonclinical samples were calculated based on community samples of subjects who had been screened and found to be asymptomatic

(24,

25) . For the Psychodynamic Functioning Scales and the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale, no normative data exist, but a score of 71 or higher is defined in the descriptive levels of the scales as normal functioning. Patients who change more than measurement error and cross the cutoff scores into the distribution of nonclinical samples are changed to a clinically significant degree.