Patients with bipolar disorder are nearly twice as likely as those in the general population to be obese

(1) . Clinically significant body weight gain (defined in the literature as a ≥5% change from baseline or 5 kg)

(2) has been documented in approximately one-fourth to two-thirds of patients in studies with lithium, anticonvulsants, and atypical antipsychotics

(3 –

6) . Evidence-based treatment guidelines consider drug effects on body weight as important in selecting pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder

(6) .

Lamotrigine, which is indicated for the maintenance therapy of bipolar I disorder and for the treatment of epilepsy, was associated with stable body weight in both clinical trials of epilepsy and bipolar disorder in which patients were not selected with respect to baseline body weight

(7,

8) . This analysis was undertaken to examine the effects of long-term treatment with lamotrigine, lithium, or placebo on weight in obese and nonobese patients with bipolar I disorder.

Method

Data from two 18-month maintenance studies designed to compare the safety and efficacy of lamotrigine or lithium with those of placebo in adults (age ≥18 years) with bipolar I disorder were combined for analysis

(9) . In an 8- to 16-week open-label preliminary phase, lamotrigine was titrated to a target of 200 mg/day (minimum dosage of 100 mg/day). Other psychotropic medications needed to treat acute symptoms were discontinued before a 76-week double-blind, random assignment phase. For this post hoc report, changes in weight from day 1 of the random assignment phase were analyzed for patients receiving lamotrigine in dosages of 100 mg/day to 400 mg/day and summarized by body mass index category: obese (body mass index ≥30 kg/m

2 ) and nonobese (body mass index <30 kg/m

2 )

(10) . All patients who received at least one dose of study medication (N=556) were included in this analysis.

Mean changes in weight during the randomly assigned treatment period were analyzed with a mixed-model repeated-measures analysis. Beyond 52 weeks of random treatment assignment, a high frequency of patients withdrew from the studies because of interventions for mood episodes, adverse events, and other reasons. Therefore, only data up to 52 weeks of randomly assigned treatment were included in the analysis. The initial model included treatment, study, body mass index category on the first day of randomly assigned treatment, ≥7% weight change during the preliminary phase, and gender as covariates. The final models consisted of treatment, study, and ≥7% weight change during the preliminary phase. All comparisons were performed in a two-sided manner at an alpha level of 0.05. Differences in weight change between groups were tested with an F value. Differences in baseline disease characteristics were tested by using analysis of covariance with adjustment for study.

Results

A total of 155 obese patients and 399 nonobese patients received at least one dose of study medication during the randomly assigned phase. The obese patients had earlier ages of onset for depression than the nonobese patients (mean=21.8, SD=10.9, versus mean=24.1, SD=12.4, respectively) (F=4.01, df=1,546, p<0.05) and reported a greater number of manic mood episodes in their lifetimes (mean=11.0, SD=17.7, versus mean=7.3, SD=8.7, respectively) (F=11.64, df=1,544, p=0.001). Other baseline characteristics were similar between treatment groups (data not shown).

The majority of the patients (N=145, 92% obese; N=374, 94% nonobese) had been treated with at least one medication for bipolar disorder before study entry. The most common prestudy treatments for bipolar disorder included lithium (N=87, 60% obese; N=231, 62% nonobese), benzodiazepines (N=68, 47% obese; N=206, 55% nonobese), antipsychotics (N=61, 42% obese; N=192, 51% nonobese), and valproate (N=76, 52% obese; N=124, 33% nonobese).

The total dose of lamotrigine was mean=248.6 mg/day (SD=87.4) in the obese patients and mean=245.3 mg/day (SD=85.5) in the nonobese patients. The corresponding doses for lithium were mean=838.8 mg/day (SD=281.4) and mean=844.2 mg/day (SD=231.8). In the lithium group, serum lithium levels during the random assignment phase were mean=0.68 meq/liter (SD=0.17) in the obese patients and mean=0.71 (SD=0.16) in the nonobese patients.

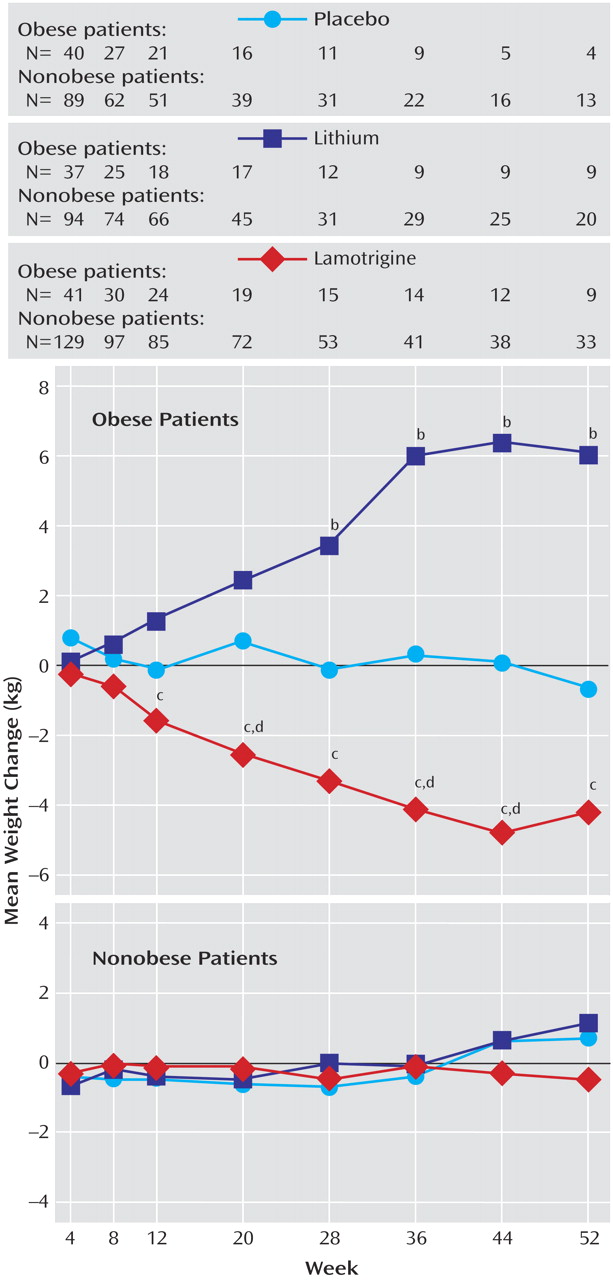

Among the obese patients, significant (p<0.05) decreases in weight were observed for those taking lamotrigine compared with placebo at weeks 20, 36, and 44 and for those taking lamotrigine compared with lithium at weeks 12, 20, 28, 36, 44, and 52 (

Figure 1 ). Significant increases in weight were observed for those taking lithium compared with placebo at weeks 28, 36, 44, and 52. Among the nonobese patients, no significant differences in mean weight change were observed among groups at any time during the random assignment phase.

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this analysis is the first to assess the effects of lamotrigine, lithium, and placebo on weight in a group of obese and nonobese patients with bipolar disorder. In the obese patients with bipolar I disorder, maintenance therapy with lamotrigine was associated with moderate weight loss, whereas maintenance therapy with lithium was associated with marked weight gain. In contrast, weight did not change in the nonobese patients, regardless of treatment group. These data are consistent with prospective and retrospective evaluations of the effects of lamotrigine on weight in patients with epilepsy

(7) .

Differences in weight between those taking lithium and those taking placebo were not statistically significant until week 28, which suggests that weight gain is a relatively late-developing correlate of lithium therapy. Unexpectedly for lithium, weight gain was essentially limited to a group of patients with preexisting obesity. One possible explanation is that certain individuals who are susceptible to obesity in general are also susceptible to lithium-induced weight gain. Better characterization of such risk factors or, conversely, protective factors might allow use of lithium without resultant weight gain in appropriately selected patients.

The differential effects of lithium in obese and nonobese patients should be interpreted cautiously. Lithium was the most frequent prior treatment used, and many patients in the study may have experienced lithium-associated weight gain before study entry. Thus, this study may have underestimated weight gain with lithium.

The results should also be interpreted in the context of the post hoc nature of the analyses and the fact that the studies were not prospectively designed to examine change in weight as a primary outcome. The post hoc analysis plan provided for use of data through the time at which observations were sufficient to comply with assumptions for the underlying statistical models. Data were truncated at 52 weeks because of patient attrition, which was larger for the lithium-treated patients than for the lamotrigine-treated patients. Random assignment yielded similar weight distribution across treatment groups at baseline. Covariates, which can confound the primary outcome, were used in the analyses to mitigate differential effects across groups.

In conclusion, the obese patients with bipolar I disorder lost weight while taking lamotrigine and gained weight while taking lithium. The nonobese patients did not gain weight, regardless of treatment group.