Symptomatic overlap between affective disorders and schizophrenia has long been noted. Even the psychotic, or “positive,” symptoms most closely identified with schizophrenia—Schneider’s first-rank symptoms—also occur in patients with affective disorder

(1). This overlap and other considerations have led some investigators to challenge the dichotomous Kraepelinian classification of the psychoses

(2,

3). Recently, overlap has also been noted in the findings from genetic linkage studies of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Four chromosomal regions that could potentially harbor susceptibility genes for both disorders have been identified: 10p12–13, 13q32, 18p11.2, and 22q11–13 (reviewed in reference

4). In spite of the limitation imposed by the generally low resolution of linkage data, this overlap has renewed interest in the hypothesis that there are susceptibility genes that contribute to the psychotic manifestations of both bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.

If psychosis genes exist, they may lead to familial aggregation of psychotic symptoms in subjects with familial bipolar disorder. There are suggestions from prior studies that psychotic symptoms cluster in some families with affective disorder, although the evidence to date has been limited. To our knowledge, only one prior study

(5) has specifically addressed the hypothesis that psychotic bipolar disorder aggregates in families; the finding was negative in a small study group. In another study

(6), in which bipolar disorder and major depression were grouped together, relatives of probands with psychotic affective disorder had a higher rate of psychotic affective disorder than did relatives of nonpsychotic probands, although the difference was not statistically significant. Two studies

(7,

8) have provided evidence of familial aggregation of psychotic symptoms in major depression, although in only one of these

(7) did the finding reach significance. A follow-up study

(9) failed to replicate this significant finding.

Discussion

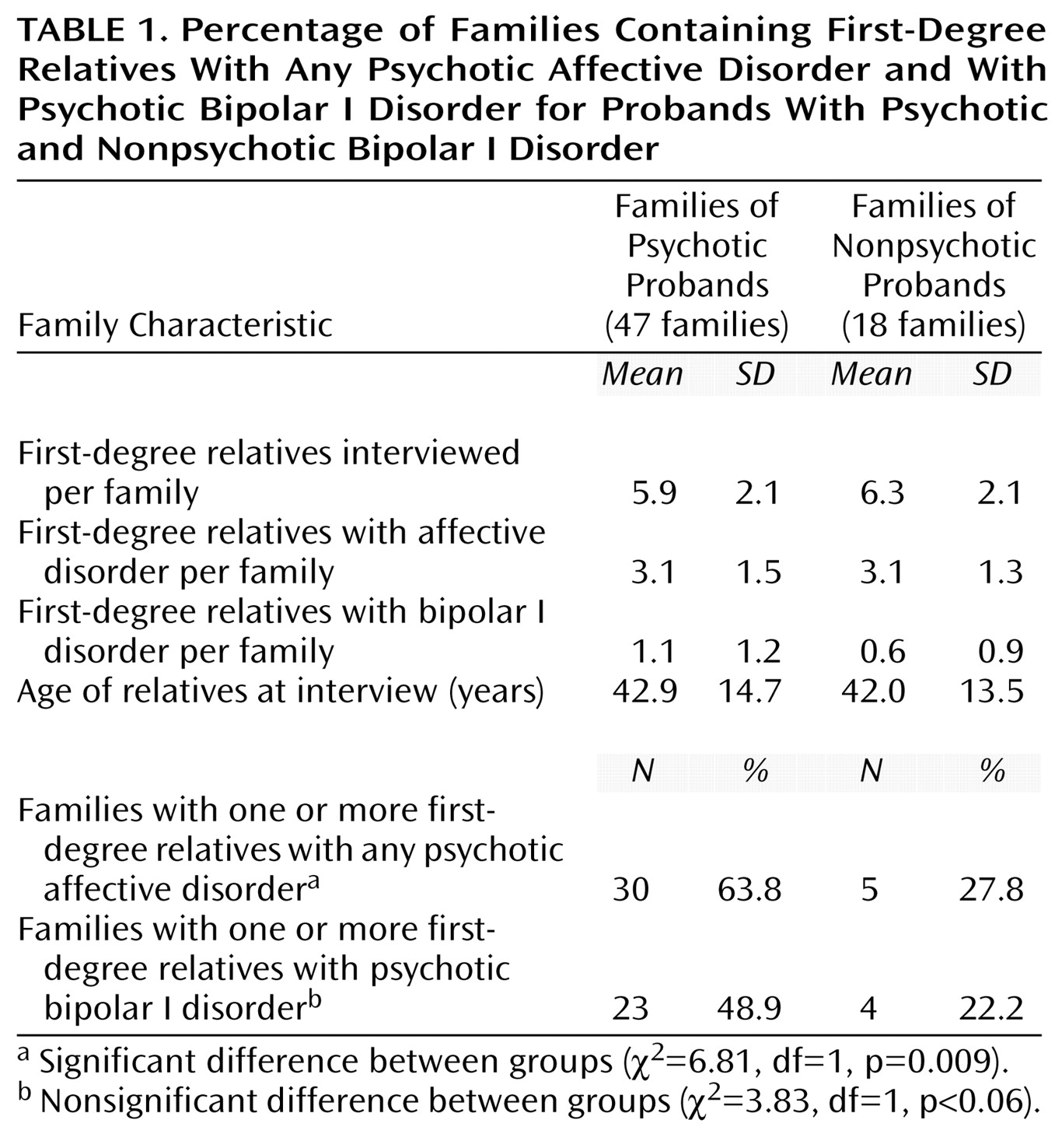

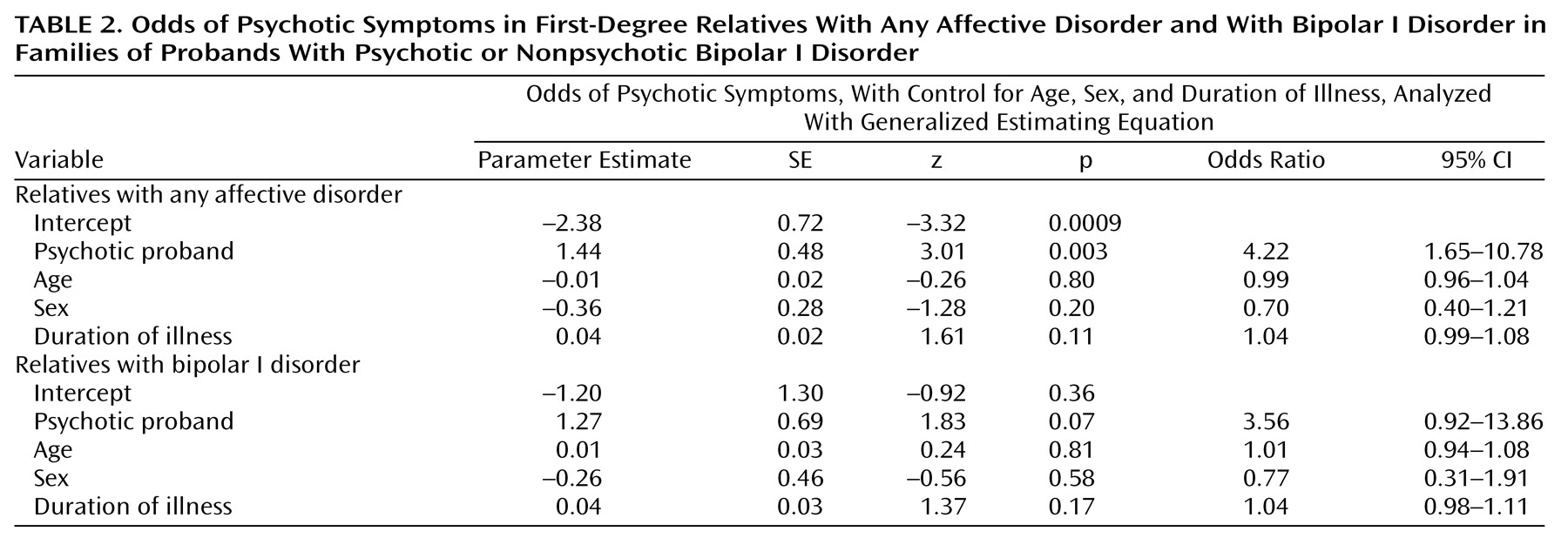

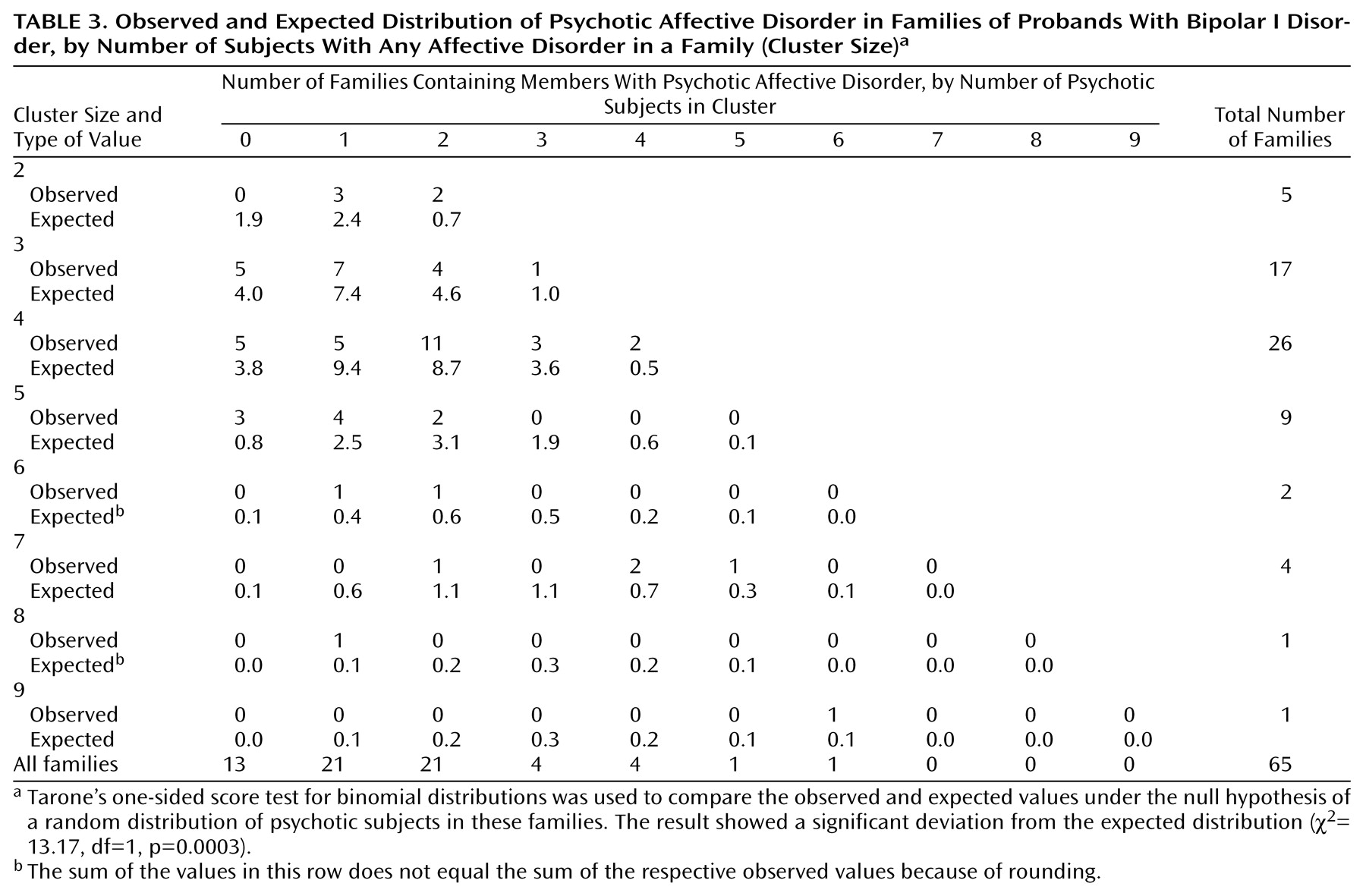

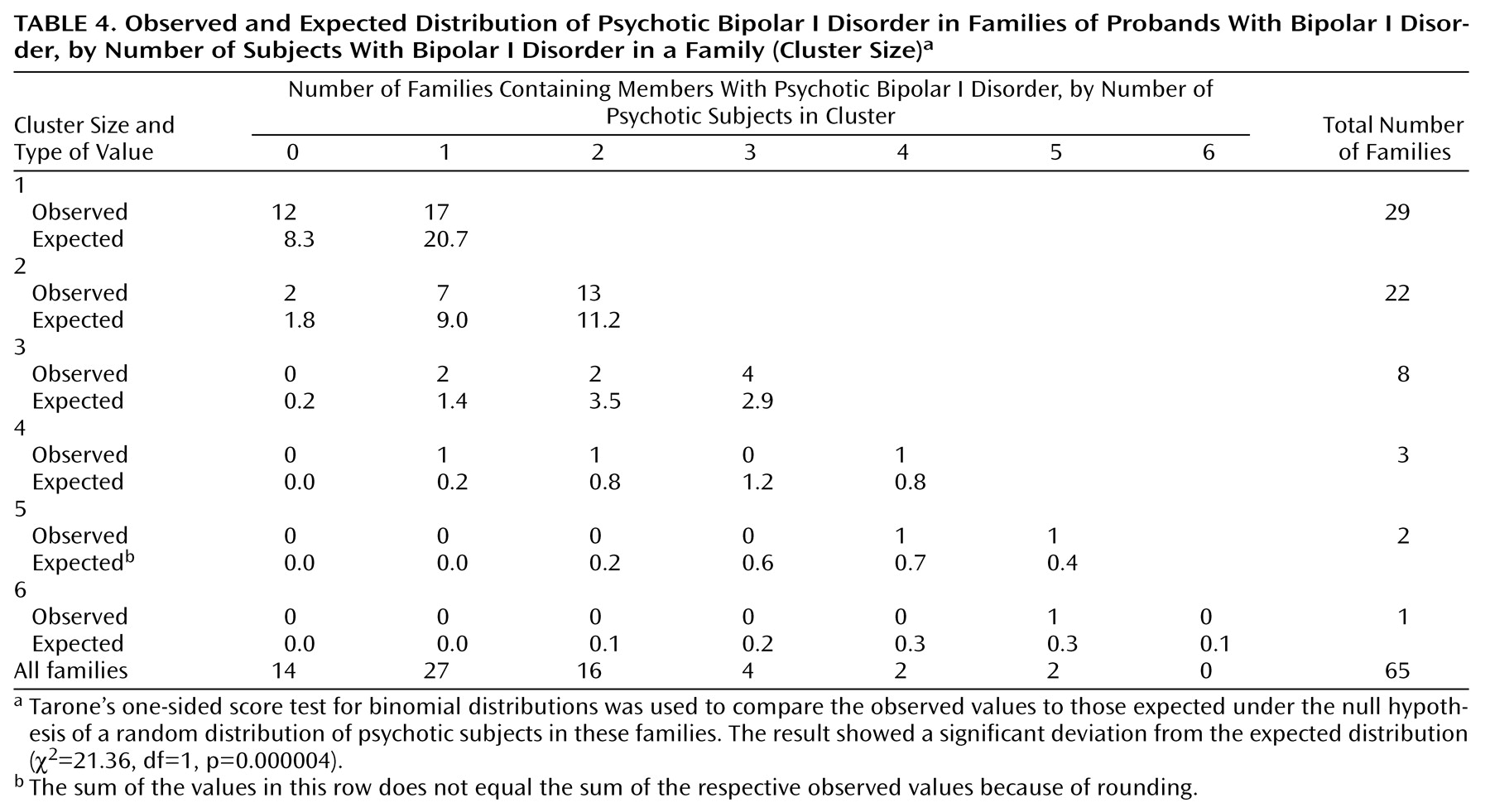

We have found evidence for the familial aggregation of psychotic symptoms, defined as hallucinations or delusions, in bipolar disorder pedigrees. Four analyses support this: 1) more families with psychotic probands than with nonpsychotic probands had at least one first-degree relative with psychotic affective disorder; 2) among the first-degree affectively ill relatives of psychotic probands, there was a higher rate of psychosis than among comparable relatives of nonpsychotic probands; 3) psychotic affective disorder clustered disproportionately in a subset of families; and 4) the clustering of psychosis was also apparent when only subjects with bipolar I disorder were considered as affected.

A strength of this study is that all of the diagnostic interviews were done by psychiatrists, thus maximizing the chance of eliciting valid reports of psychotic symptoms. In addition, the reliability of the assessment of hallucinations and delusions with the SADS-L has previously been demonstrated to be excellent

(13). The test-retest reliability for the diagnosis of psychotic bipolar disorder was also found to be good to excellent in another study using the SADS-L

(17). Even so, the SADS-L assesses only the most severe manic and depressive episodes; it does not require the interviewer to ask about each lifetime episode, so that a psychotic affective episode could be missed.

This study used a narrow definition of psychosis. We did not assess formal thought disorder or disorganized behavior even though these features are often considered psychotic. Although formal thought disorder is assessed by the SADS-L, it has been shown to have lower reliability than hallucinations and delusions

(13). Prior analyses of the structure of psychosis

(18) have suggested that hallucinations and delusions may be independent of thought disorder and disorganization, however, so that our narrow definition of psychosis may be helpful in our pursuit of a genetically more homogeneous subtype of bipolar disorder.

We considered whether hallucinations and delusions were just one aspect of a broader severity that was familial. No statistically significant differences in most severity indicators were found between relatives in the families of psychotic and nonpsychotic probands. However, two significant differences were found: an excess of bipolar I disorder subjects and more hospitalizations in the families of psychotic probands. The higher rate of hospitalization is not surprising given that psychotic symptoms generally lead to impaired judgment and thus to potential dangerousness. The finding that a higher rate of psychosis is associated with a higher rate of bipolar I disorder is not unexpected given that mania is associated with a substantially higher rate of psychosis than is depression

(19). Among the relatives with psychotic bipolar I disorder, all but two experienced psychosis during mania (the two exceptions were psychotic only during depression). In order to assess whether the clustering of psychosis in families was independent of the clustering of bipolar I disorder in families, we did separate analyses in which we considered only bipolar I disorder as the affected phenotype. Analysis by family and analysis by individual relative yielded differences in the rate of psychosis between proband groups that were not statistically significant. Application of the third analytic method to the phenotype of bipolar I disorder only, however, resulted in a highly significant clustering of psychosis; this latter method had more power than the first two to detect familial aggregation of psychotic symptoms because, by including probands, it took into account more than double the number of subjects with bipolar I disorder.

These results are consistent with some

(6–

8), but not all

(5,

9), previous findings on familial aggregation of psychotic affective disorder. One study, by Winokur et al.

(5), specifically had a negative result in a study group restricted to bipolar disorder. One explanation for the difference between that result and ours may lie in the different inclusion criteria used: the Winokur et al. study used only relatives with psychiatric records (N=43), whereas we assessed all available relatives. Our study group therefore included 108 relatives without psychiatric records among 137 total relatives with bipolar disorder (after exclusion of relatives of probands with schizoaffective disorder, manic type, and recurrent unipolar depression, as in the study by Winokur et al.). The relatives with records were significantly more likely to be psychotic than those without records. Among our bipolar disorder relatives with records, 48.3% (14 of 29) were psychotic, whereas among those without records the figure was 28.7% (31 of 108) (χ

2=3.97, df=1, p=0.05). Because the Winokur et al. analysis omitted those without records, many nonpsychotic relatives may have been excluded, and, in the presence of familial aggregation of psychotic symptoms, those excluded would have been disproportionately relatives of nonpsychotic probands, thus biasing the study group toward a negative finding.

Our findings should be considered in the context of other studies of several types that have yielded evidence to support the utility of subtyping by the presence of psychosis. These can be grouped into clinical studies, family studies, and biological studies.

1. Clinical studies have included those that assessed symptoms, course of illness, and treatment response. Two studies using factor analysis to assess the underlying structure of symptoms in mania have demonstrated an independent psychotic factor based on the presence of hallucinations and delusions

(20,

21). One study

(22) was an assessment of the factor structure of familial bipolar disorder and produced evidence for the three-factor model of negative, psychotic, and disorganized dimensions. Investigations on the course of illness have shown that, compared to nonpsychotic bipolar subjects, subjects with psychosis have an earlier onset

(23), more impaired functioning over time

(24–

26), and a higher rate of relapse at 4-year follow-up

(24). One study, however, did not show differences in functioning

(27). The findings of studies assessing treatment response have been more equivocal

(28–

31).

2. Family studies have suggested shared liability between psychotic affective disorder and schizophrenia, although the evidence for overlapping liability between bipolar disorder (irrespective of psychotic symptoms) and schizophrenia is less strong. Three large data sets have been studied to address the issue of overlap between schizophrenia and psychotic affective disorder

(6,

32–

35). In all three, higher than expected rates of psychotic affective disorder in relatives of schizophrenic probands, and vice versa, were found. Methodologically rigorous studies

(36–

38), however, have not shown an excess of schizophrenic relatives in families of probands with bipolar disorder or an excess of relatives with bipolar disorder in families of probands with schizophrenia; excess rates of major depression and of schizoaffective disorder were found in both types of families.

3. Biological studies have focused on brain imaging and on neurophysiology. One study

(39) indicated anomalous brain asymmetry in the postcentral gyrus in psychotic, but not nonpsychotic, subjects with bipolar disorder. A functional imaging study

(40) demonstrated high dopamine D

2 receptor densities in patients with psychotic, but not nonpsychotic, bipolar disorder; the high levels were similar to those seen in schizophrenia patients. Evidence for shorter REM latency in psychotic than in nonpsychotic subjects with depressive episodes (some of whom had bipolar disorder) has been found

(41). In two brain imaging studies

(42,

43) subjects with psychotic affective disorder and those with schizophrenia had abnormally low volumes of similar regions: the left hippocampus in one study

(42) and the left posterior amygdala-hippocampal complex in the other

(43).

If subtyping bipolar disorder by the presence of psychosis is biologically meaningful, at least two scenarios seem plausible: there might be a vulnerability to psychosis and a separate vulnerability to bipolar disorder, or there might be a particular vulnerability to psychotic bipolar disorder. Given that psychosis is familial in our study group, either the separate vulnerabilities or the particular vulnerability may be the result of genetic influences. Either scenario would be consistent with the hypothesis that genes increase susceptibility to both psychotic bipolar disorder and to schizophrenia: the separate psychosis vulnerabilities might reflect shared psychosis genes because delusions and hallucinations occur in both disorders; the particular psychotic bipolar disorder vulnerability might reflect genes that predispose to psychotic symptoms and to affective symptoms because affective symptoms frequently co-occur with psychosis not only in bipolar disorder, but also in schizophrenia—there is a high rate of depressive symptoms in schizophrenia

(44), and this co-occurrence may be familial

(45,

46). Studying bipolar disorder families enriched for the psychotic bipolar disorder subtype could yield greater power to detect genes leading to either of the vulnerabilities described. In this regard, the chromosomal regions 10p12–13, 13q32, 18p11.2, and 22q11–13, which have been implicated in both bipolar disorder and schizophrenia

(4), are of particular interest. Further study of families with psychotic bipolar disorder should also focus on putative schizophrenia-associated biological markers, including abnormalities in evoked response, oculomotor, neuroimaging, and cognitive measures

(47).

In summary, our data demonstrate that hallucinations and delusions during affective episodes show familial aggregation in bipolar disorder pedigrees. This finding suggests the value of using the psychotic bipolar disorder subtype in genetic and biological investigations. Such investigations may inform the discussion about possible etiologic overlap between bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.