It has been suggested that serotonergic dysfunction is involved in the pathophysiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

(1). To date, studies of the association between OCD and variants of genes coding for serotonergic (HT) structures have produced contrasting results; in particular, the functional polymorphism of the promoter region of the 5-HT transporter gene has been found to be associated with OCD

(2,

3), as has a 5-HT

2A receptor gene polymorphism

(4).

Sumatriptan, a selective ligand of the serotonin 5-HT

1Dβ autoreceptor, modifies OCD symptoms

(5,

6); the 5-HT

1Dβ receptor gene can therefore be considered as a candidate gene in conferring susceptibility to OCD. Recently, Mundo et al.

(7) reported linkage disequilibrium between OCD and a silent G-to-C substitution at nucleotide 861 of the coding region of the 5-HT

1Dβ receptor gene

(8) in a study with a family-based design.

Applying the transmission/disequilibrium test, we tested the association of this polymorphism in nuclear families of OCD probands.

Method

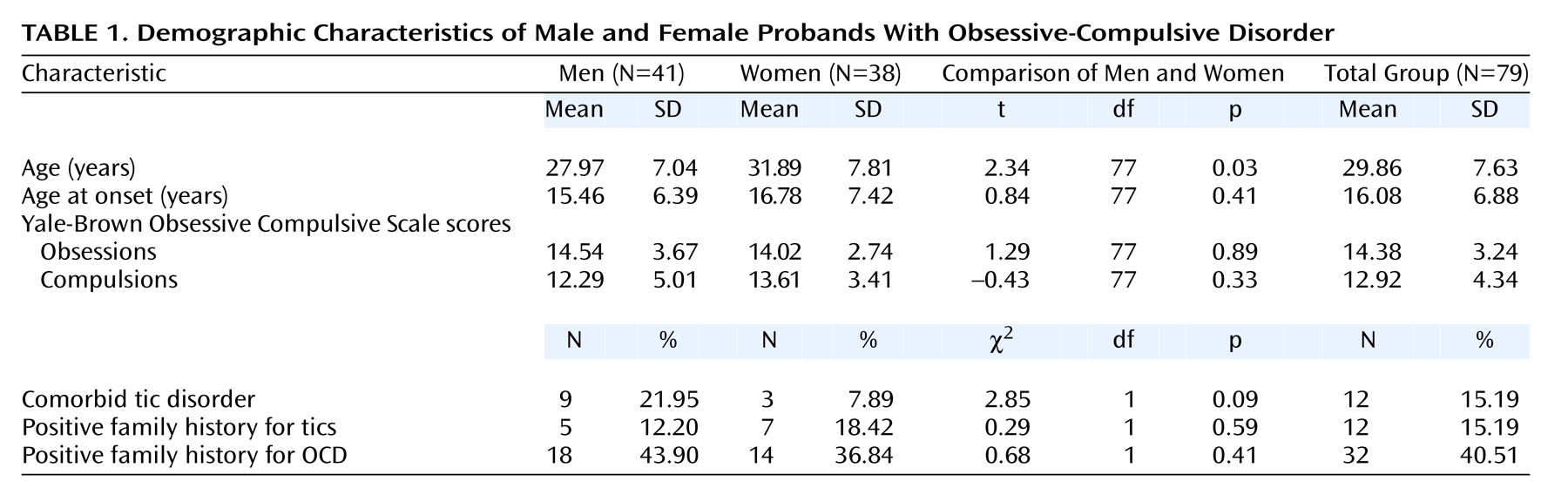

From consecutive admissions to the anxiety disorders unit of San Raffaele Hospital, we recruited 79 OCD probands who each had two available parents. The probands were diagnosed according to DSM-IV diagnostic criteria by means of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, and the severity of the disorder was evaluated with the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale

(9) by trained clinical psychiatrists. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. Clinical characteristics of the study group are summarized in

Table 1.

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood

(10); the G-to-C substitution was typed by polymerase chain reaction, restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis (

HincII digestion), and gel electrophoresis, as described elsewhere

(8).

Chi-square statistics and Student’s t test were applied for between-sexes comparisons of clinical variables.

The transmission/disequilibrium test was applied as implemented by Spielman and colleagues

(11,

12). The transmission/disequilibrium test evaluates the preferential allelic transmission from parents to offspring; the degree of a disease-gene association is estimated by the frequency with which heterozygous parents transmit the putative high-risk allele to the affected offspring. Only families in which both parents are genotyped and at least one parent is heterozygous are informative for the analysis.

Mundo et al.

(7) estimated an increased risk associated with the G allele of 5.26 (95% confidence interval=1.92–13.10). In our OCD group the frequencies of the G and C alleles were 79.75% and 20.25%, respectively. Assuming alpha = 0.01 and 1 – beta = 0.8, we performed a power analysis by applying the method supplied by Knapp for the one-sided transmission/disequilibrium test

(13). Power analysis revealed that 46 families was the minimum number required for detecting that risk and that our OCD group had the power to detect a minimum detectable risk of 3.01.

Results

The genotype frequencies in the proband group were as follows: GG, 63.29% (N=50); GC, 32.91% (N=26); and CC, 3.80% (N=3). As just indicated, the frequencies of the G and C alleles were 79.75% and 20.25%, respectively.

The genotypic distribution was not significantly different from the distribution expected according to Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in the probands, fathers, and mothers. No difference between fathers and mothers in genotype distribution was present.

Genotyping of the total study group revealed that 48 probands had at least one heterozygous parent; these families were therefore included in the analysis.

No differences were observed for allelic transmission from heterozygous parents to their offspring (χ2=2.40, df=1, p=0.13). The G allele was transmitted 36 times and not transmitted 24 times. The C variant was transmitted 24 times and not transmitted 36 times.

No differences in transmission were observed when the families were considered according to age at onset of OCD in the proband, proband tics, or positive family history for OCD or tics (data not shown).

Discussion

Our results do not confirm an involvement of the 5-HT1Dβ receptor gene in conferring susceptibility to OCD.

One possible explanation for this result could stem from the clinical heterogeneity of OCD. From a clinical point of view, our study group could be different from the group studied by Mundo et al. For example, the baseline score on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale of our patients was 27.31 (SD=6.06), which is significantly higher than that observed by Mundo et al. (t=6.33, df=144, p<0.001), while the frequency of comorbid tics was lower in our OCD group (χ

2=8.25, df=1, p=0.004)

(7). These clinical differences could point to genetic differences between the groups, identifying OCD subphenotypes, and could therefore partially account for the discrepant results.

Recently Hollander and Pallanti

(14) suggested that a 5-HT

1Dβ receptor gene variant may be involved in the liability to repetitive behaviors, rather than in the liability to a diagnostic category. As for other complex disorders, a polymorphic gene could influence only a small part of the phenotypic variance, and more factors, both genetic and environmental, have to interact in determining the clinical phenotype.

In our patients, the 5-HT

1Dβ receptor gene could play only a minor role with a smaller increase of risk, which could be undetectable with our group size. In fact, even if power analysis revealed that our group size is adequate to identify the mean effect reported by Mundo et al., the minimum risk detectable by our study is 3.01 and is higher than the lowest effect (1.92) identified within the 95% confidence interval by Mundo et al.

(7).

Population-based differences, particularly in the extent of linkage disequilibrium between the tested polymorphism and other potential variants in the gene, could also be responsible for the discrepant finding.

In conclusion, the 5-HT1Dβ receptor gene is not unequivocally involved in OCD, and we think it will be necessary to identify and study more homogeneous clinical phenotypes (identified, for example, by age at onset, illness duration, comorbid tics, pharmacological response) to define better the role of this and other gene variants in the etiopathogenesis of OCD.