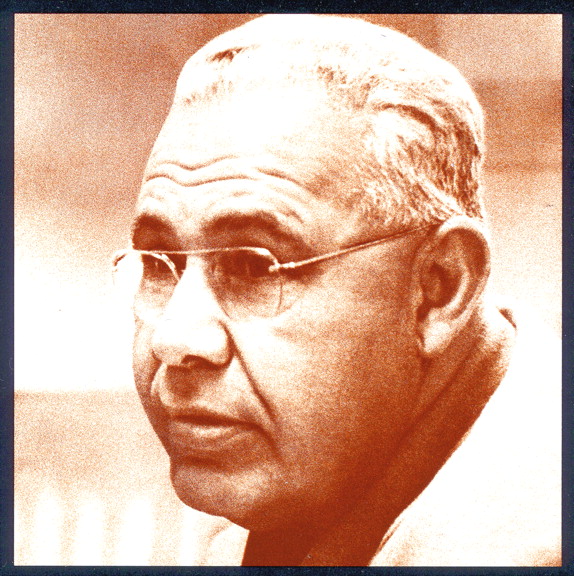

Franz Alexander was born in Budapest. A brilliant first graduate of the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute, he was invited in 1930 by Robert Hutchins, then President of the University of Chicago, to become its Visiting Professor of Psychoanalysis—the first University Chair of Psychoanalysis in history. In 1932, he founded the Chicago Psychoanalytic Institute, which under his dynamic leadership acquired world-wide renown as an outstanding psychoanalytic training and research center. Among his personal trainees were such distinguished colleagues as Karl and William Menninger, Leo Bartemeier, and Gregory Zilboorg.

Alexander was a rare psychoanalytic pioneer who, despite a thorough grounding in classical Freudian theory, had the courage, vision, and flexibility to modify his thinking in the light of newer knowledge. His productivity ranged creatively over fields as diverse as psychosomatic medicine, sociology, philosophy, criminology, and the visual arts. Most of all, however, he deserves to be credited as the person who brought psychoanalysis out of its isolation from medicine, building meaningful bridges between it and the rest of psychotherapy.

A landmark contribution toward this process was the 1946 publication of his book

Psychoanalytic Therapy, co-authored with Thomas M. French

(1). The volume created an enormous uproar in orthodox psychoanalytic circles, and he was vilified for “muddying the pure waters of psychoanalysis.” Its publication was the culmination of 7 years of prior research into the development of shorter, more efficient techniques of psychotherapy, initiated by his long-standing puzzlement at “the baffling discrepancy between the length and intensity of [psychoanalytic] treatment and degree of therapeutic success” and by the fact that severe neurotic conditions would sometimes “yield to brief therapeutic work,” yet other relatively milder cases would fail to respond to many years of intensive psychoanalytic treatment.

Alexander asserted that the essence of the analytic process was bringing into the patient’s consciousness emotions and motivations of which he or she was unaware, and thereby extending control over behavior “in actual life, in relation to [family members], superiors, competitors, friends and enemies.” He argued that so long as psychotherapy attempted to achieve these goals through the application of psychodynamic principles, the therapy was psychoanalytically oriented regardless of its length or frequency of visits. He stated that efforts to set up sharp lines of demarcation between “true” psychoanalysis and briefer methods of dynamic psychotherapy were confusing the “rituals” of analytic technique with the “essence” of the analytic process.

Alexander died prematurely of pneumonia in California—at a time when he was still intellectually vigorous and creative—but his place in psychiatric history is secure.