The natural history of borderline personality disorder is not yet known. Those who pioneered the description of the syndrome suggested that its outcome was malign, making comparisons with schizophrenia

(1). However, in recent years, a more optimistic view is frequently expressed. It is supposed that borderline personality disorder “burns out,” the manifestations of the disorder becoming less disabling in the fourth and subsequent decades.

The burn-out view is inferred from two main kinds of information, neither of which is satisfactory. The first category of data depends upon retrospective diagnoses. The most important of these studies involved patients who received extensive inpatient treatment

(2,

3). The second category of evidence derives from prospective studies. However, since formal recognition of the borderline personality disorder diagnosis was achieved only in 1980, such studies necessarily concern a period in the patient’s life that is too short to accurately indicate the life course of borderline personality disorder.

Another difficulty with the burn-out hypothesis relates to the heterogeneity of the borderline personality disorder syndrome. The Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (DIB-R) distinguishes four categories of symptoms

(4): interpersonal difficulties, cognitive disturbance, affective disturbance, and impulsivity. If burn out is characteristic of borderline personality disorder, what burns out? Do all four categories tend to dissipate, or does impulsivity alone decline? This study attempts to answer this question. The design is vertical, compared with previous longitudinal studies. In this case, rather than following a cohort of patients with a particular condition throughout its course, patients are studied at one point in the course. A collection of these assessments provides a preliminary picture of the natural history

(5).

Method

A total of 154 adults were screened for inclusion in the Westmead Psychotherapy Program, which offers outpatient psychotherapy for individuals with borderline personality disorder. Referrals came from inpatient settings, community health centers, medical centers, and psychiatrists. Individuals were excluded if they had language difficulties, intellectual impairment, antisocial personality disorder, organic cerebral impairment, an ongoing psychotic disorder, or failed to meet the diagnostic criteria for borderline personality disorder.

Following the method of a previous study

(6), all potential participants were screened at an assessment interview with the Westmead Severity Scale

(6) and the DIB-R

(4). The Westmead Severity scale is a semistructured clinical interview that provides a clinical diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. Interrater reliability of the scale is very good (kappa=0.81) (M. Lassere, 1999, unpublished report, Westmead Hospital). The DIB-R is a semistructured interview that allows quantification of the core features of the disorder (affective disturbance, relationship disturbance, cognitive disturbance, and impulsive behavior).

This study concerns data collected at the assessment interview of 123 individuals who were accepted for treatment. The mean age of the group was 31.56 years (SD=8.25, range=18–52), and the mean level of education was 11.16 years (SD=1.96, range=9–15). (The age range reflects the inclusion criteria for our program.) There were 24 men and 99 women. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

Results

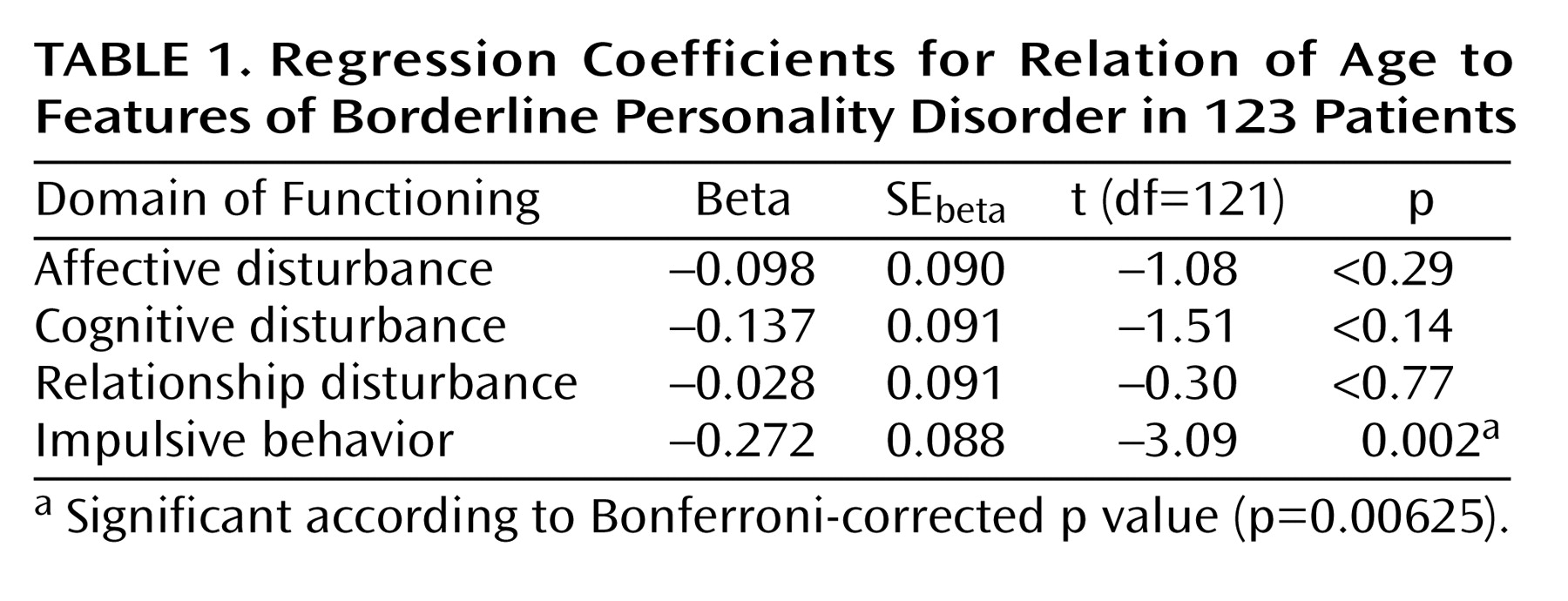

The aim of the analysis was to determine the relationship between age and the outcome variables affective disturbance, relationship disturbance, cognitive disturbance, and impulsive behavior. Scores for these domains of functioning were derived from subsection scores of the DIB-R. Four linear regression analyses were performed, one for each outcome variable. The p values associated with the regression coefficients were adjusted for multiple comparisons by using the Bonferroni method. From these analyses, only impulsive behavior was significantly associated with age; older participants were less likely to engage in impulsive behavior (

Table 1).

Discussion

In this study of 123 participants with borderline personality disorder, younger participants showed significantly more impulsive behavior than older participants. Age did not predict interpersonal disturbance, cognitive disturbance, or affective disturbance. This finding suggests that a putative “maturing out” or burning out with age in borderline personality disorder is only partial and that, although impulsivity declines, the less behaviorally salient but equally disabling features of affective disturbance, interpersonal difficulties, and cognitive disturbance may not ameliorate. This mirrors the finding that the behavioral manifestations burn out with age

(7). Other factors not considered here may correlate with the decline in impulsivity (e.g., use of medication, comorbid diagnoses, employment status, DSM criteria). These would need to be explored in a more detailed analysis.

The findings are consistent with those of Stone

(3), who, in an extensive review observed that whereas impulsive features are less pronounced in later life, identity disturbance persists. Nevertheless, this study must be considered preliminary since the concept of impulsivity as defined by DIB-R needs clarification and refining. It does not include cognitive factors. It is a behavioral index that covers a range of risk taking and potentially harmful behaviors that may have various etiologies

(8). This study is also preliminary in that we studied a select group. All subjects came from tertiary referrals and were characterized by treatment failure and significant morbidity and thus represent a particular selection of a borderline personality disorder population.

These findings lead to a questioning of the view that impulsivity is the fundamental enduring feature of borderline personality disorder

(9). The persistence with aging of interpersonal problems and affective instability support the view that these are the nuclear features of borderline personality disorder

(10,

11).

Finally, this study brings into doubt a widely held view that affect dysregulation and impulsivity are linked in borderline personality disorder

(12). If they were linked, it would be expected that a decline in impulsivity with aging would be accompanied by an equivalent decline in affective disturbance. The fact that our findings do not show this equivalent decline suggests a need to further explore the relationship between impulsive behavior and affective disturbance.